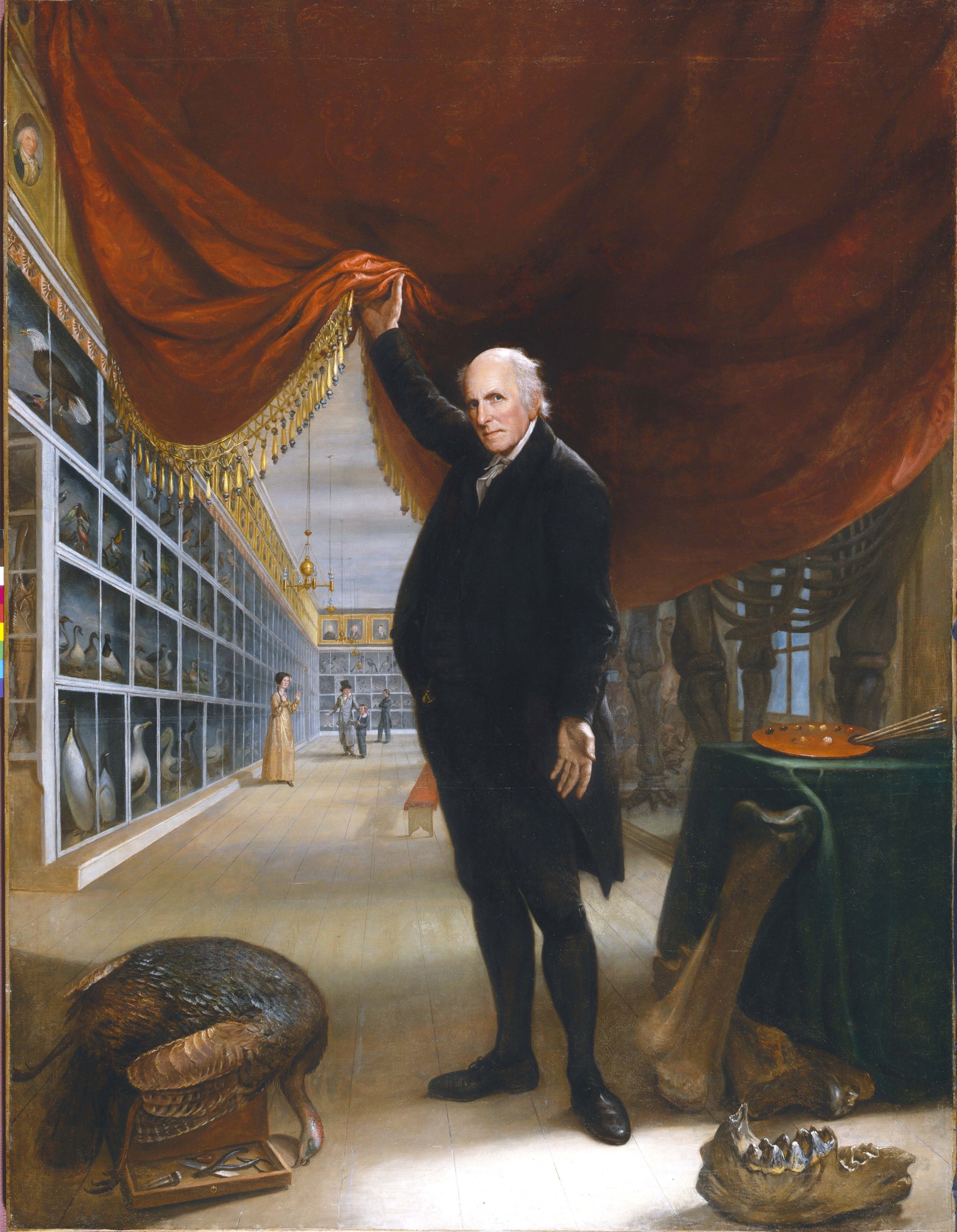

“The Artist in His Museum” by Charles Willson Peale (American, 1741-1827), 1822, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Gift of Mrs Sarah Harrison (The Joseph Harrison Jr Collection). 1878.1.2. Adrian Cubillas photo.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

PHILADELPHIA — On January 10, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) president Eric Pryor wrote in an open letter to the PAFA community that the institution will cease granting degrees at the end of the 2024-25 academic year. Citing rising costs and shrinking enrollment, Pryor characterized it as a difficult decision that nevertheless “presents PAFA with an opportunity to return to our roots.” While the organization’s commitment to arts education remains strong, it seems clear that its future will be increasingly tied to the other half of its longstanding public face: its museum and its remarkable collection. “Making American Artists: Stories from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1776-1976” was planned long before this decision was made about PAFA’s future, but, as it turns out, it will play a key role in paving the way forward. Following its presentation at PAFA last year, the exhibition will travel to six venues throughout the United States, beginning with the Wichita Art Museum through April 21.

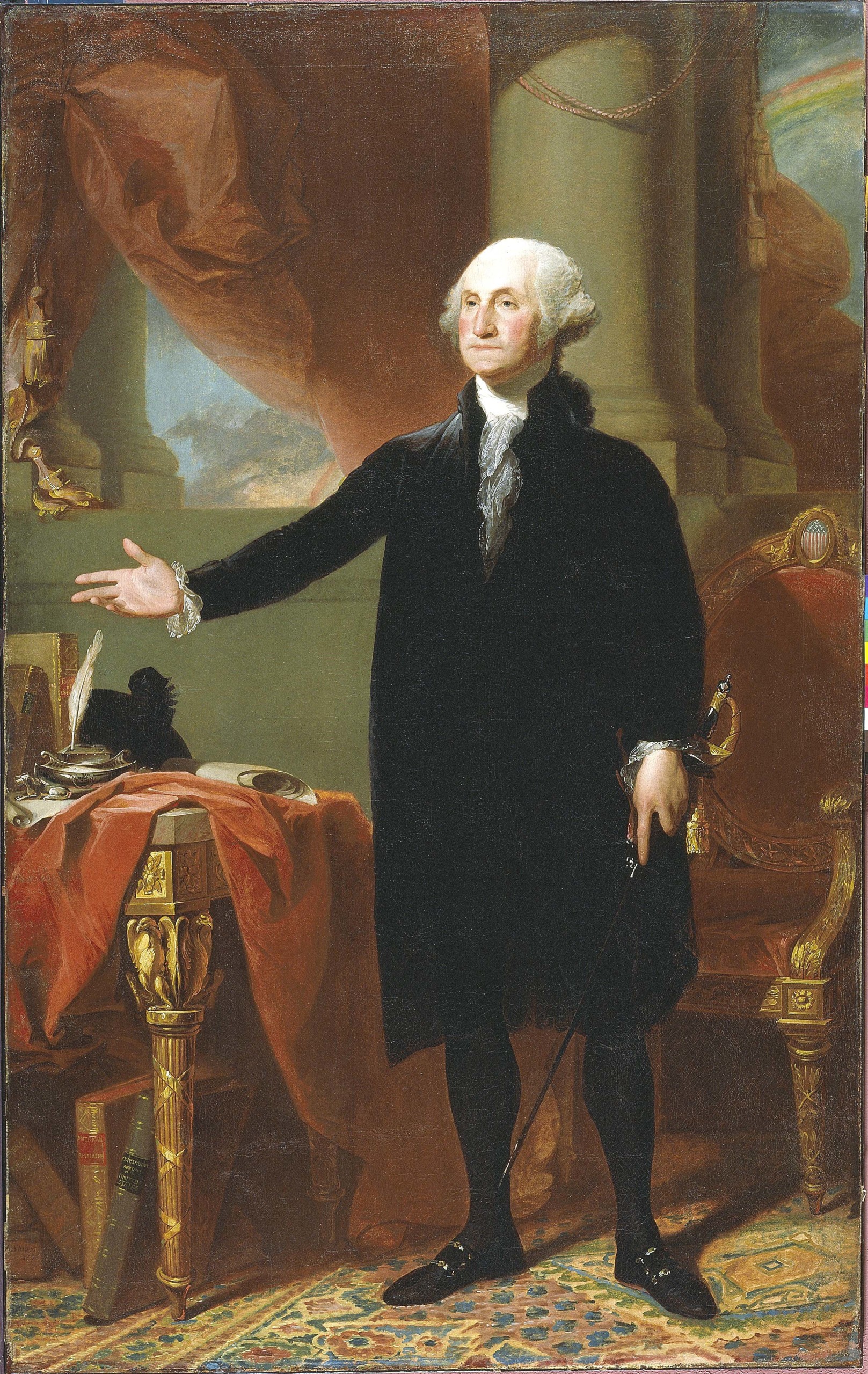

In 1805, PAFA was founded by artists — specifically Charles Willson Peale and Benjamin Rush — as the first art school and museum in the United States. One of the things that makes the recent announcement so jarring is that its mission has remained astonishingly consistent throughout its two centuries of existence. While similar institutions have publicly and privately struggled to adapt their collections, exhibitions and educational programs to serve broader audiences, PAFA has always had a comparatively inclusive approach. At the time of its founding, it was revolutionary to collect American art at all — what even was “American” art fewer than 30 years after the nation’s founding? — and yet, among the museum’s first acquisitions were important paintings by Gilbert Stuart and Washington Allston, who helped to define the genre. Remarkably, early exhibitions and acquisitions also included works by women artists, beginning with the first annual exhibition in 1811, when PAFA director Joseph Hopkinson stated his wish to include “the products of female genius.” Certainly, artists like Margaretta Angelica Peale and her sisters also benefited from their familial relationship with founder Charles Willson Peale — but their breathlessly pristine still lifes hold their own, now and then.

“Baby on Mother’s Arm” by Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926), circa 1891, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. Bequest of Peter Borie, 2003.15. Adrian Cubillas photo.

PAFA’s commitment to educating women artists, particularly those connected to Philadelphia (Mary Cassatt, we’re looking at you), and exhibiting and collecting their work has been consistent throughout its history. Anna O. Marley, PAFA’s chief of curatorial affairs and curator of “Making American Artists,” marvels at how students at the turn of the century would have had the opportunity to study under both William Merrit Chase (famously supportive of his women students, including Georgia O’Keeffe) and Cecilia Beaux (“the first full-time woman professor of art in the nation”) at the same time. “Think about what that must have been like to be a young woman who could have those two mentors in one place in the late Nineteenth Century,” she says. That commitment endured through the Twentieth Century and into the present, with major figures like Philadelphia native Alice Neel entering PAFA’s collection, and a recent exhibition, “Rising Sun: Artists in an Uncertain America,” bringing contemporary installation pieces by several women not only into the museum’s Nineteenth Century Historic Landmark Building but also into PAFA’s permanent collection.

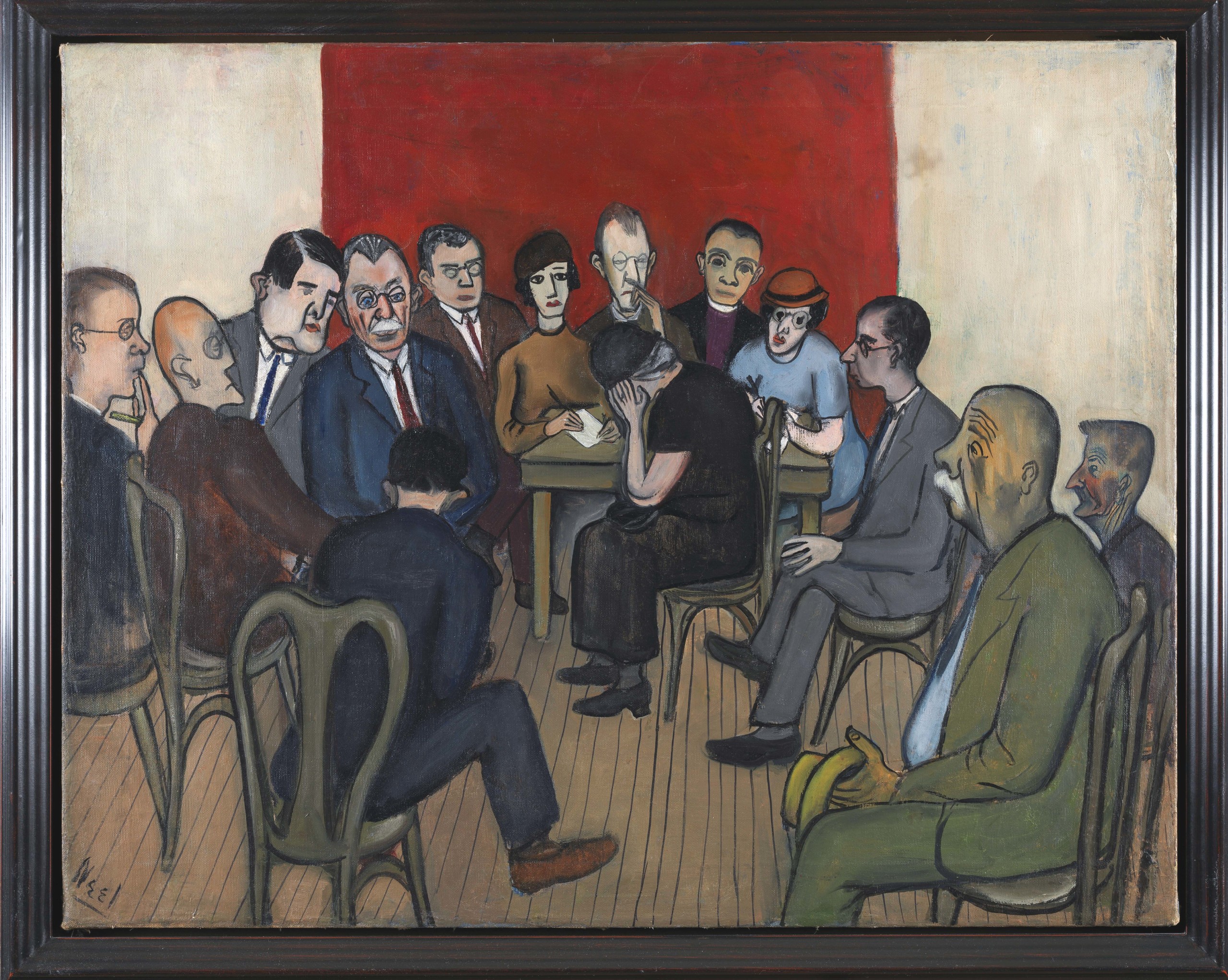

“Rising Sun,” co-organized with the African American Museum in Philadelphia, coincided with “Making American Artists” at PAFA, and, as such, it offered something of a sequel to that more historical show. Artists for “Rising Sun” were asked to respond to the question, “Is the sun rising or setting on the experiment of American democracy?” — reflecting the similar concerns of many of the artists featured in “Making American Artists.” Benjamin West’s “Penn’s Treaty with the Indians” (1771-72) and Edward Hicks’s “The Peaceable Kingdom” (circa 1833), for instance, take somewhat optimistic views, offering pleasing fictions of harmonious coexistence. Others, like Horace Pippin’s “John Brown Going to His Hanging” (1942) or Alice Neel’s “Investigation of Poverty at the Russell Sage Foundation” (1933) deal more frankly with the failings and fault lines of the American democratic experiment.

“Investigation of Poverty at the Russell Sage Foundation” by Alice Neel (American, 1900-1984), 1933, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. Art by Women Collection, Gift of Linda Lee Alter, 2010.27.2. ©The Estate of Alice Neel, Courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner. Adrian Cubillas photo.

Marley planned “Making American Artists” to be organized around general subject themes, and in the “history painting” section visitors are meant to encounter Pippin’s work first, before West’s. “I wanted those two to be visually in conversation,” says Marley, “and I hung ‘John Brown Going to His Hanging’ before ‘Penn’s Treaty’ so that you would be forced to confront a work that you might see as modernist or folk or self-taught before you saw this academic history painting — because I wanted people to think about the constructedness of history painting.”

The prominence of Black artists (like Pippin) in both “Rising Sun” and “Making American Artists” underscores another important aspect of PAFA’s history. Although PAFA was ahead of the curve, with respect to other American arts institutions, in admitting Black students to its school and welcoming their work into its annual exhibitions and museum collections, it only did so a good 50 years into its existence. Scholar Dana Byrd’s essay in the Making American Artists catalog takes a broad look at the history of Black art at PAFA, beginning with the Peale family’s complex legacy as supporters of abolition and founders of a forward-looking institution in one of the most progressive and diverse cities of the young nation — while also being slaveholders. Peale’s magisterial “The Artist in His Museum” (1822), an icon of American art, documents the place where the family’s enslaved servant, Moses, set up a physiognotrace station for the entertainment of museum visitors, producing art of which he was the author but never the owner. Blackness is equally present but invisible in a circa 1810 portrait of a (white) woman attributed to Joshua Johnson, the earliest known professional African American artist.

“John Brown Going to His Hanging” by Horace Pippin (American, 1888-1946), 1948, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, John Lambert Fund, 1943.11. Adrian Cubillas photo.

But, by the late Nineteenth Century, PAFA’s commitment to Black artists was robust and highly visible, with May Howard Jackson and Henry Ossawa Tanner, among many others, winning prestigious awards and producing work that spoke directly to issues of race. Jackson’s “Slave Boy” and Tanner’s “Nicodemus” both present Black figures as individuals rather than caricatures, “with a cognitive life and restrained emotion,” in Byrd’s words, breaking stereotypes endemic in visual and written culture of the time. Tanner’s depiction of Jesus Christ as a man of color in “Nicodemus” was particularly boundary-pushing, then and now.

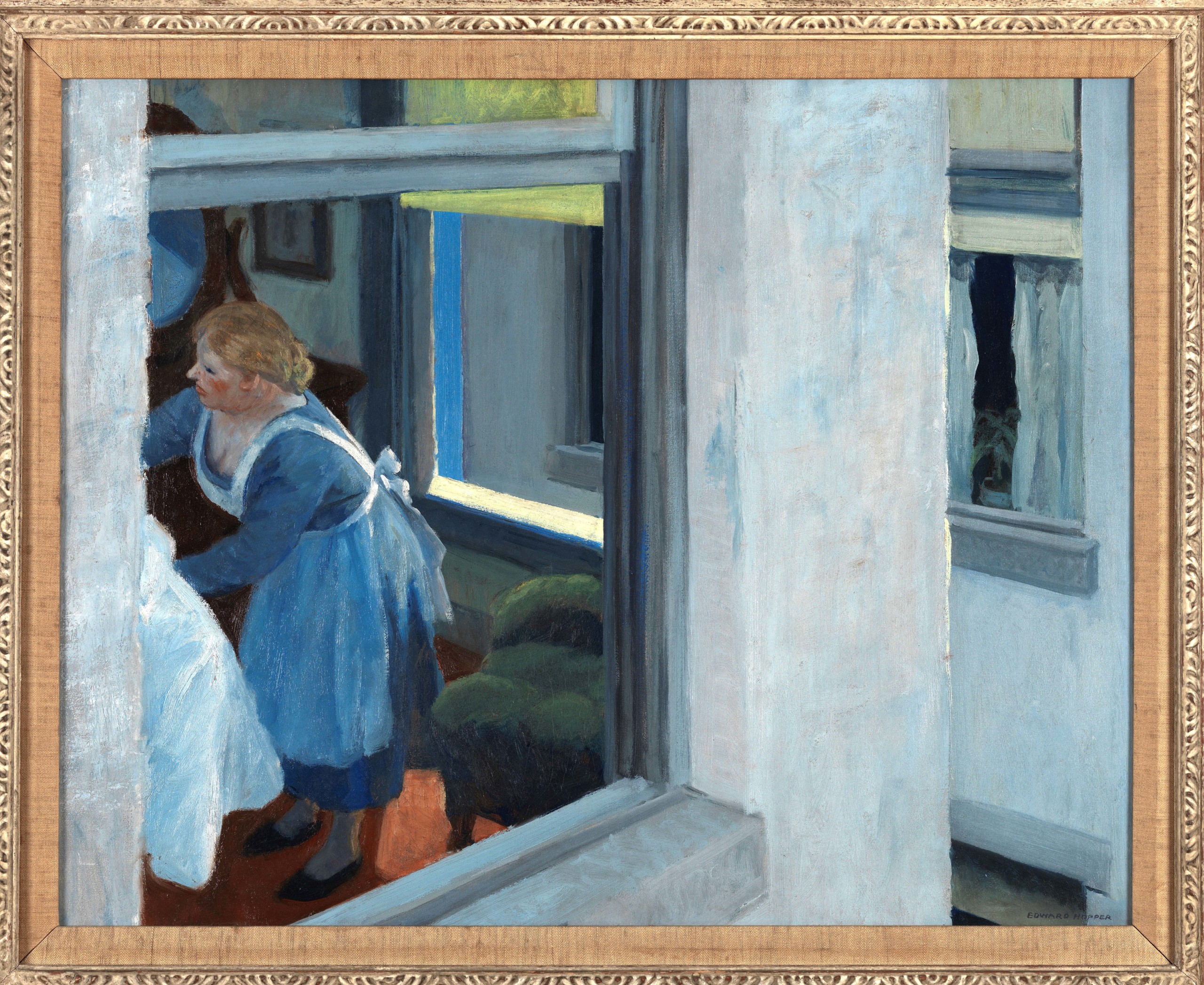

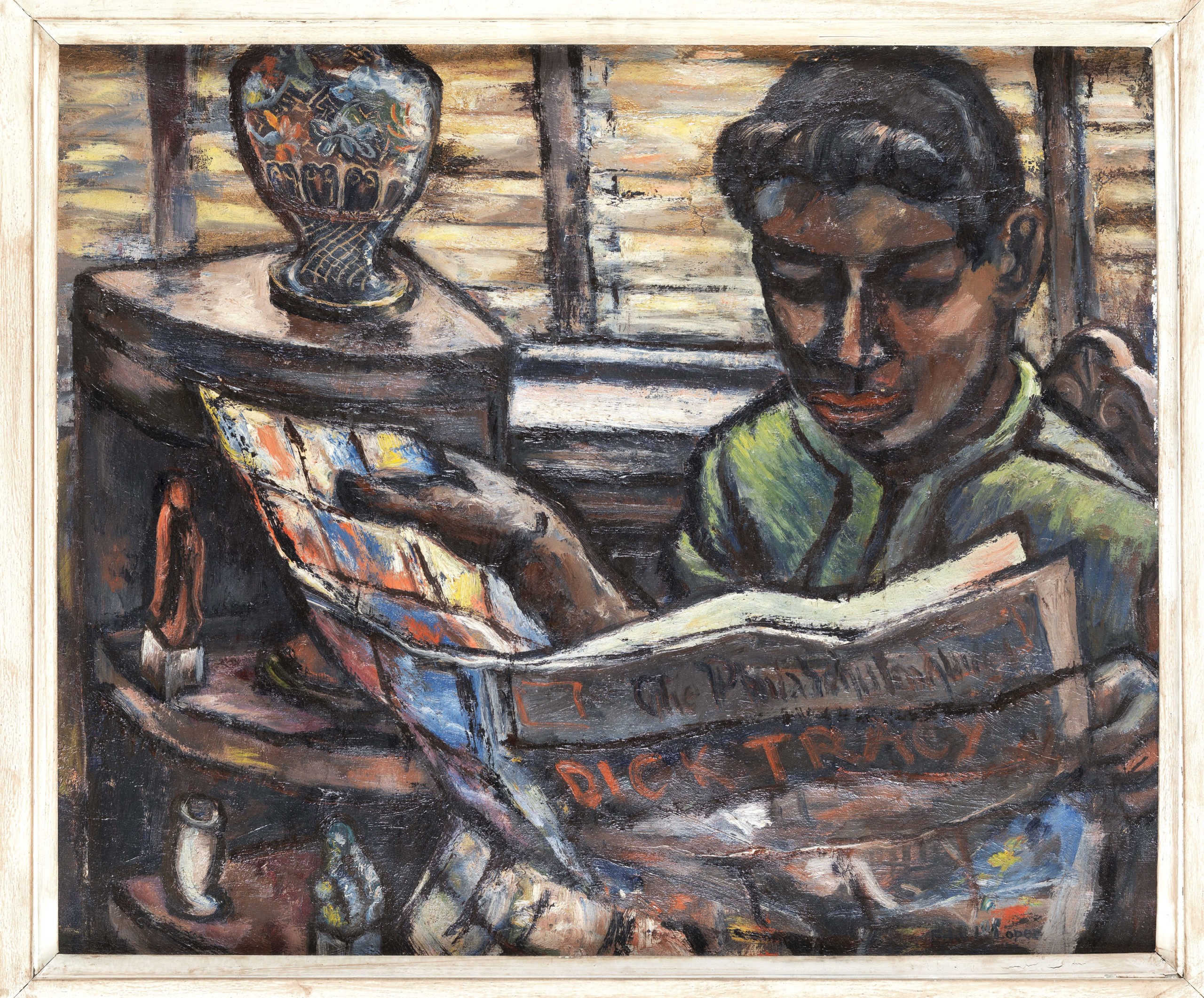

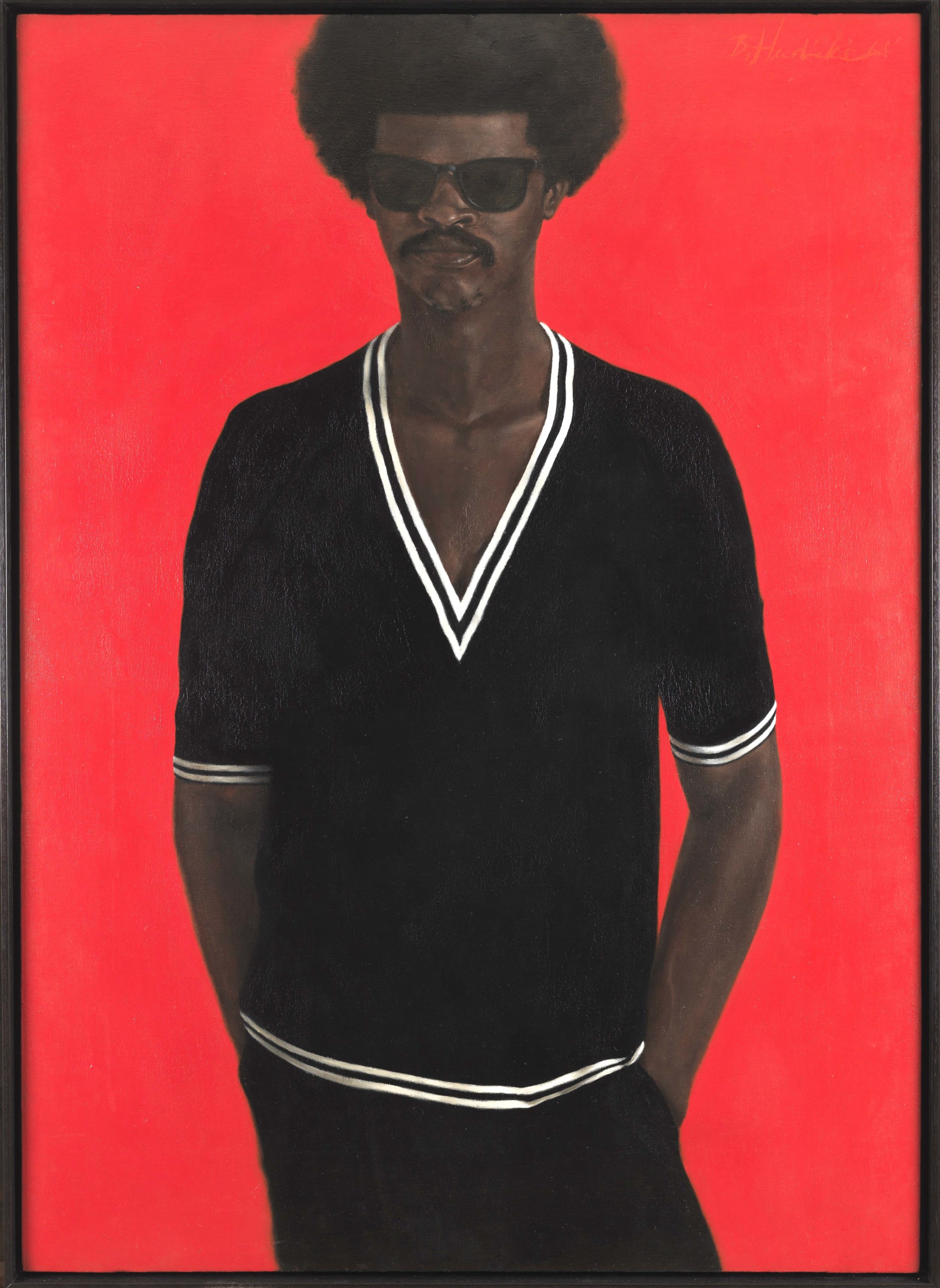

“That’s not to say that there hasn’t been discrimination and racism at the institution,” Marley cautions; “Tanner definitely felt that in the Nineteenth Century.” Indeed, Tanner famously lived out much of his career in Paris, where he experienced fewer racial restrictions on his artistic and professional opportunities. But PAFA’s commitment to Black art and artists was not just lip service, and the organization consciously sought to keep pace with a changing conversation, embracing the “New Negro” movement of the 1930s and the Black liberation movements of the 1960s and ’70s. The presence of artists like Pippin, Edward Loper, Sr, and Julian S. Bloch in PAFA’s exhibitions, collections and faculty became inspiration for a younger generation. James Brantley’s self-portrait, “Brother James,” and Barkley Hendrick’s portrait of Brantley, “J.S.B. III,” both from 1968, capture some of these intersections of influence while anticipating the work of artists like Kerry James Marshall, Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley, who continue to redefine portraiture in the context of the Black American experience.

“J.S.B. III” by Barkley L. Hendricks (American, 1917-2009), 1968, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Gift of Mr and Mrs Richardson Dilworth, 1969.17. ©Barkley L. Hendricks, Courtesy of the Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City. Adrian Cubillas photo.

There is much to celebrate about PAFA, despite the difficult transition it is about to undergo. Still, Marley says, “I wanted to strike a note with both the catalog and the exhibition of not being totally celebratory, of being self-critical and aware of absences as well as celebrating things that we got right.” That self-criticality comes into play, in part, by acknowledging the pronounced absence of Native American art from this exhibition about American art, something that Marley says some of the borrowing venues raised concerns about. Her response to them, she explained, was that, as per the exhibition title, “this show is not telling the story of American art; we are telling stories from this very particular place, Philadelphia, and this particular institution, with its strengths and its weaknesses.”

PAFA has added important works by contemporary Indigenous artists to its collection in recent years — it was recently recognized for its commitment to diversity by the Burns Halpernin report, which “explores representation in US museums and the international art market” — but it is true that its holdings of historical Native American art and artists are minimal. Still, that weakness is indeed part of the story — so rather than try to minimize it, Marley frontloaded it in the catalog with an introductory essay by Christian Ayne Crouch, a scholar of American and Indigenous studies at Bard College. “For years PAFA, like most of its peers, acquired few or no works by Native artists because these were not considered fine art,” writes Crouch, explaining that such works were instead relegated to ethnological or natural history contexts. However, sincere and enthusiastic are the Twenty-First Century attempts to redress such oversights, progress is slow, in part because museum practices did not develop with the specific needs of Indigenous art and artists in mind. The few historical objects that PAFA owns have physical limitations that do not allow them to travel safely in a six-venue nationwide tour.

“Red Canna” by Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986), 1923, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, The Vivian O. and Meyer P. Potamkin Collection, Bequest of Vivian O. Potamkin, 2003.1.8. ©2023 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. Adrian Cubillas photo.

Indeed, selecting the objects for “Making American Artists” was a fraught process, Marley says, including the trimming down of an initial 300-object checklist into 100 objects (about 75 for Wichita and two other venues, due to the size of their exhibition spaces). Consulting former PAFA curators and outside scholars, she fought hard for some pieces whose time, she felt, was due. Paintings by Loper and Sonja Sekula — an Abstract Expressionist and an out lesbian in the 1950s — had languished in storage not only because their creators were from marginalized communities but also because they lacked suitable display frames. The artists had just never had the money to frame them properly. Marley struck a deal with Gill and Lagodich, specialists in antique frames, wherein PAFA would invest in a new exhibition frame for Winslow Homer’s fan-favorite “The Fox Hunt” and they would donate their time to reframe the Loper and the Sekula. This echoes PAFA’s similar effort, 10 years ago, to cast in bronze Tanner’s bust of his father, Bishop Tanner, which the artist had not been able to afford at the time. As Marley explains, a PAFA faculty member cast that bust and it is also in the “Making American Artists” exhibition. There it offers yet another story, among the exhibition’s many, about how various kinds of marginalization, including economic ones, intersect — and how museums today can go some way to redress them or at least acknowledge them.

Part of the reason that PAFA’s collection is going on tour in this moment is that its Historic Landmark Building is undergoing renovations and will be closed until sometime in 2026. When it reopens, many of the works in “Making American Artists,” along with other highlights of PAFA’s collection, will go back on display. In the meantime, the artwork will reach a broad, in-person audience from Massachusetts to Albuquerque, N.M., and Marley and her team will be able to consider audience responses and test-drive strategies for their grand reopening in two years. Along with the cancellation of degree-granting programs, this is a major reset. “Making American Artists” will give PAFA’s leaders, as well as visitors to the exhibition in its various venues, an opportunity to confront and assess the institution’s legacy and consider what the next two centuries may bring.

“Young America” by Andrew Wyeth (American, 1917-2009), 1950, egg tempera on gessoed board (“Renaissance Panel”). Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. Joseph E. Temple Fund, 1951.17. ©2023 Andrew Wyeth / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. Adrian Cubillas photo.

“Making American Artists: Stories from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1776-1976” will be on view at the Wichita Art Museum through April 21; the Albuquerque Museum of Art, May 18-August 11; The Philbrook Museum of Art, September 21-January 5; Ackland Art Museum, February 5-May 11, 2025; Peabody Essex Museum, June 14-September 21, 2025; and the Taubman Museum of Art, October 25, 2025-January 25, 2026.

The Wichita Art Museum is at 1400 West Museum Boulevard, Wichita, Kan.

For information, 316-268-4921 or www.wam.org.