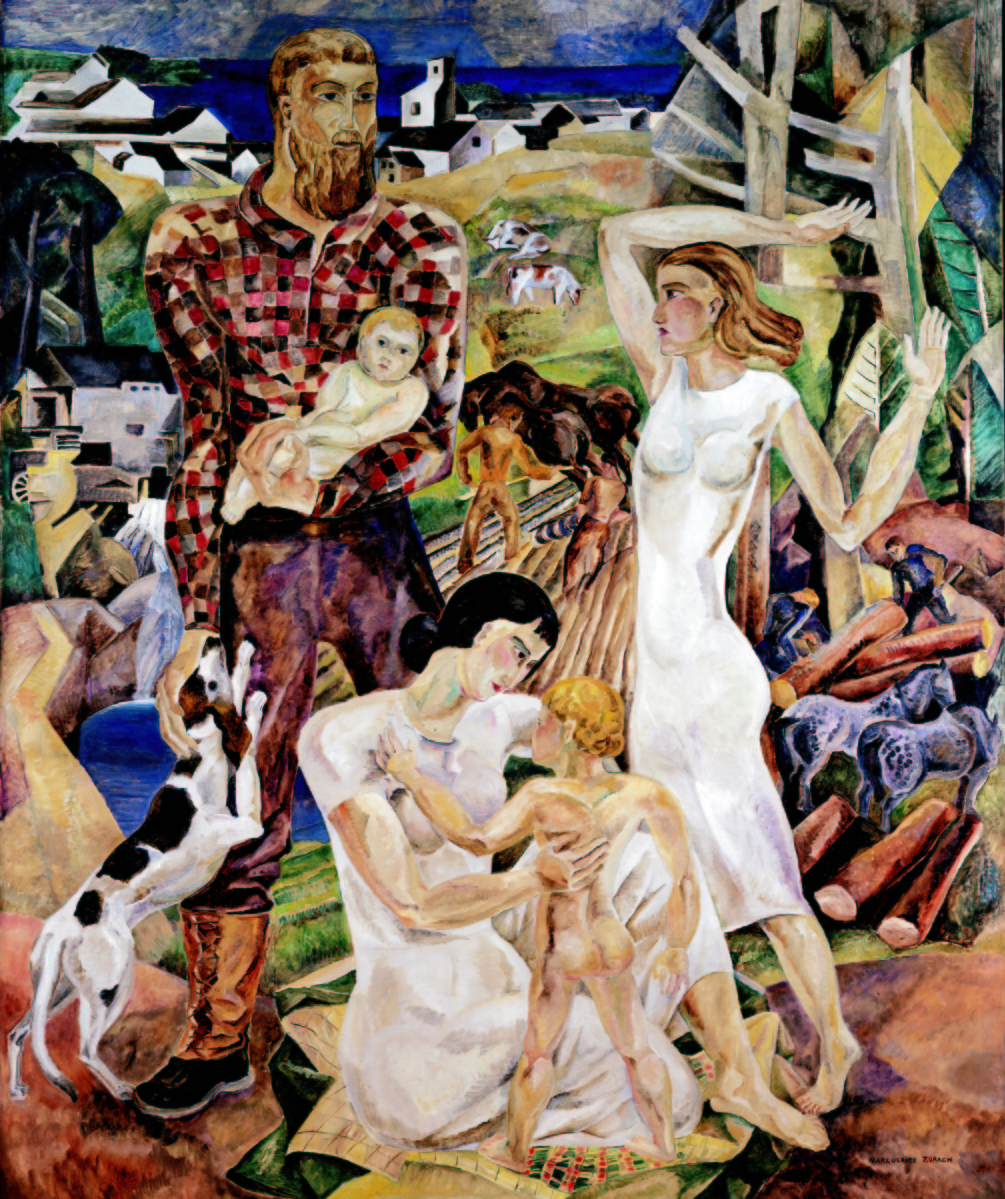

While not related to any of the WPA murals that Zorach completed, this painting explores similar themes of industry and agriculture, showing how New England was built from farming, fishing, lumber and water power. Note the male figure’s plaid flannel shirt and distinctive boots. L.L. Bean started making its iconic Maine Hunting Shoe in 1911. “Land and Development of New England,” 1935. Oil on canvas, 96 by 76 inches. Farnsworth Art Museum.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

ROCKLAND, MAINE – It is one of the paradoxes of Marguerite Thompson Zorach’s life and remarkable artistic career that she has so often been thought of in the context of someone else. In the early Twentieth Century New York art world – and in later scholarship dealing with that period – she was rarely mentioned outside of the same breath as her husband, the painter and sculptor William Zorach (1887-1966). Even in Maine, where she put down deep roots at the height of her career, she is in some circles best known as the mother of Dahlov Ipcar, the beloved artist, author and illustrator who became an unofficial artistic spokesperson for the state and died earlier this year at the age of 99.

Somewhat more individual recognition for Zorach (1887-1968) came last year in the form of “O’Keeffe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach: Women Modernists in New York,” organized by the Norton Museum of Art. Still, astonishingly, “Marguerite Zorach: An Art-Filled Life” is the artist’s first solo museum retrospective. It is on view through January 7 at the Farnsworth Art Museum – an anchor institution in the Midcoast Maine region where Zorach increasingly lived her life from the mid-1920s on.

As firmly as Zorach has come to be associated with Maine, she actually lived a peripatetic and cosmopolitan life when she was younger. In every way except being born a woman – educational and exhibition opportunities still being very limited for women artists at the turn of the previous century – she was destined to be a leading Modernist. She grew up in a prosperous, educated family in Fresno, Calif., and was encouraged to study art abroad. She gravitated toward the most avant-garde art schools and movements, blending wild Fauve colors with the decorative elements she saw in Parisian studios, theaters and design shows. A world tour with an aunt in 1911-12 further introduced her to the arts of the Middle East, India and East Asia, spurring an interest in textiles and patterns that characterized the rest of her career.

While in Paris she also met and fell in love with a young Lithuanian student, Zorach Gorfinkel. After a brief separation, while she was back in California painting landscapes, they married in 1912 and made the mutual and unconventional decision to change both their names, adopting Zorach as their new surname (he changed his given name to William at this time, while she kept hers). They settled in New York’s Greenwich Village, determined to build a life together that was focused on art. Their work from this period looks very much alike, so it is somewhat excusable that scholars today often think of them interchangeably. What is less reconcilable is that critics at the time generally saw Marguerite Zorach’s work as a kind of gloss to that of her husband, much to the couple’s chagrin. Frustration over this reality undoubtedly led her to become the founding president of New York’s Society for Women Artists in 1925.

While in Paris she also met and fell in love with a young Lithuanian student, Zorach Gorfinkel. After a brief separation, while she was back in California painting landscapes, they married in 1912 and made the mutual and unconventional decision to change both their names, adopting Zorach as their new surname (he changed his given name to William at this time, while she kept hers). They settled in New York’s Greenwich Village, determined to build a life together that was focused on art. Their work from this period looks very much alike, so it is somewhat excusable that scholars today often think of them interchangeably. What is less reconcilable is that critics at the time generally saw Marguerite Zorach’s work as a kind of gloss to that of her husband, much to the couple’s chagrin. Frustration over this reality undoubtedly led her to become the founding president of New York’s Society for Women Artists in 1925.

The Zorachs’ loving, mutually supportive and lifelong partnership is ineluctably a defining factor in their art. However, until recently it has only been William’s art that has been seen in its own light, outside the sheltering context of their relationship and family life. Farnsworth associate curator Jane Bianco seeks to redress that with this landmark exhibition, admitting that in doing so she “sort of artificially extracted” William’s works from those on view. Doing that has allowed visitors the opportunity to appreciate the uniqueness of Marguerite Zorach’s art and to follow the threads of her own personal history as they both intertwine with and stand apart from the fabric of her famous family.

Bianco remembers that the genesis of the present show was the Farnsworth’s 2010 exhibition “Rug Hooking in Maine,” curated by Mildred Peladeau, which heightened awareness among museum staff in an aspect of Zorach’s textile art. Peladeau introduced Bianco to Ipcar and to Peggy Zorach, Marguerite and William’s daughter-in-law. Both women were still living at the family compound in Georgetown, Maine, Peggy in the house that Marguerite Zorach had decorated with wall paintings and filled with art, both her own and the folk art she collected.

Bianco began to conceptualize an exhibition that would focus exclusively on Marguerite Zorach’s work and would draw special attention to her textiles. “I was thrilled that we were able to bring in as many pieces as we could,” says Bianco – some 20 examples, plus more than 35 paintings and other works.

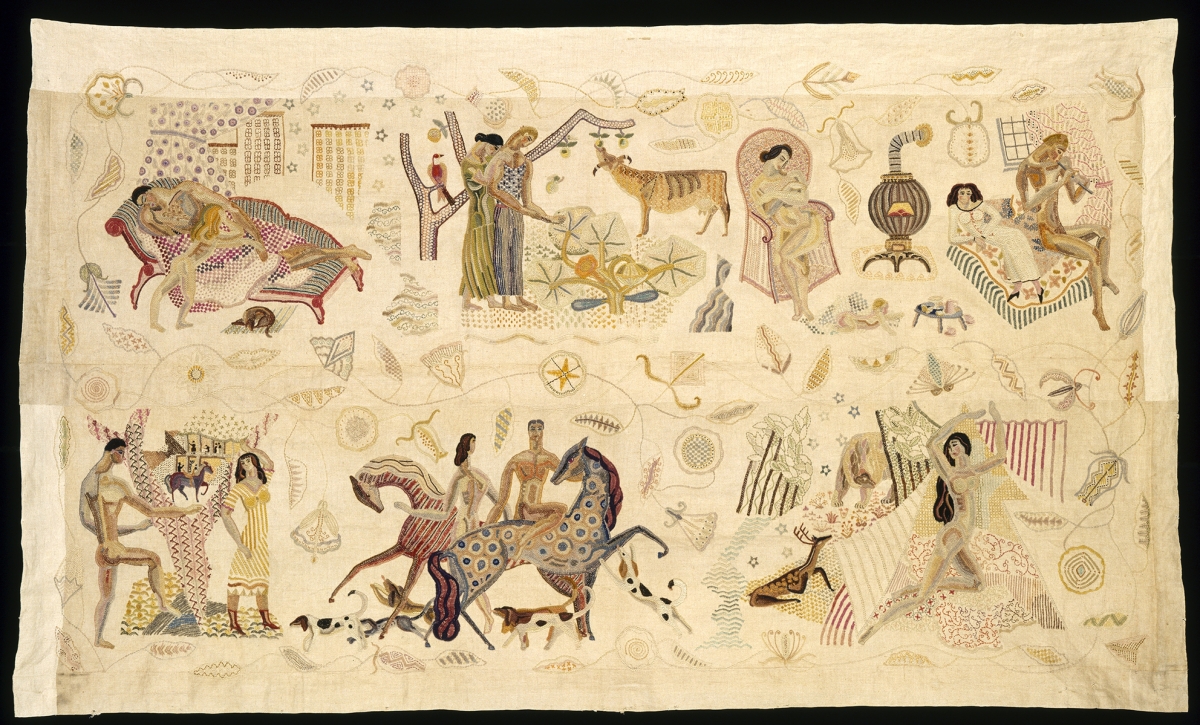

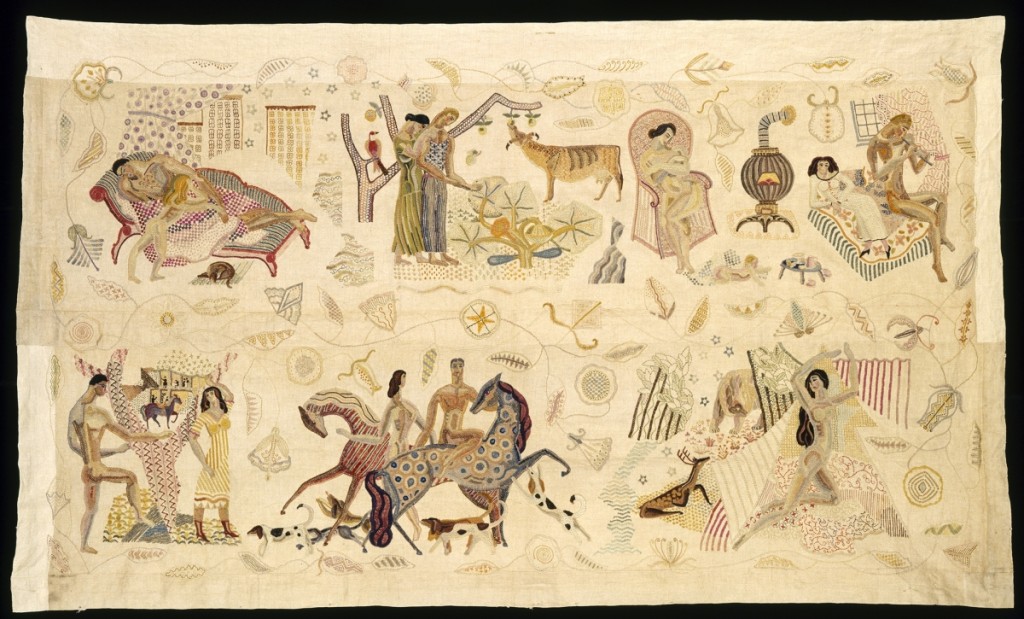

This remarkable object is in fact a modern reassembly of an elaborate, four-part bedcovering Zorach made as a commission for a patron. These are the two side panels, stitched together sometime in their history. This exhibition has reunited them with the foot panel, now in a private collection. Embroidered panel, 1925–28. Polychrome wool embroidered on linen, 53-7/8 by 91-1/8 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

One reason, perhaps, that Zorach’s artistic reputation has often been overshadowed by her family members is that her family was a major part of her work. In those early years in Greenwich Village, when she was making her name as an artist, she was also starting a family, and her work as a result often (though not always) focused on her domestic world (her husband’s often did, too, it bears noting). This was partly a reality and a necessity – primary responsibility for child-rearing fell to her as it did to all women at the time – but it was also clearly a legitimate artistic fascination. “She entered into that Bohemian life,” says Bianco, “all the while keeping that traditional value of family and the family unit,” a theme that recurs throughout her work in all media and in all phases of her career.

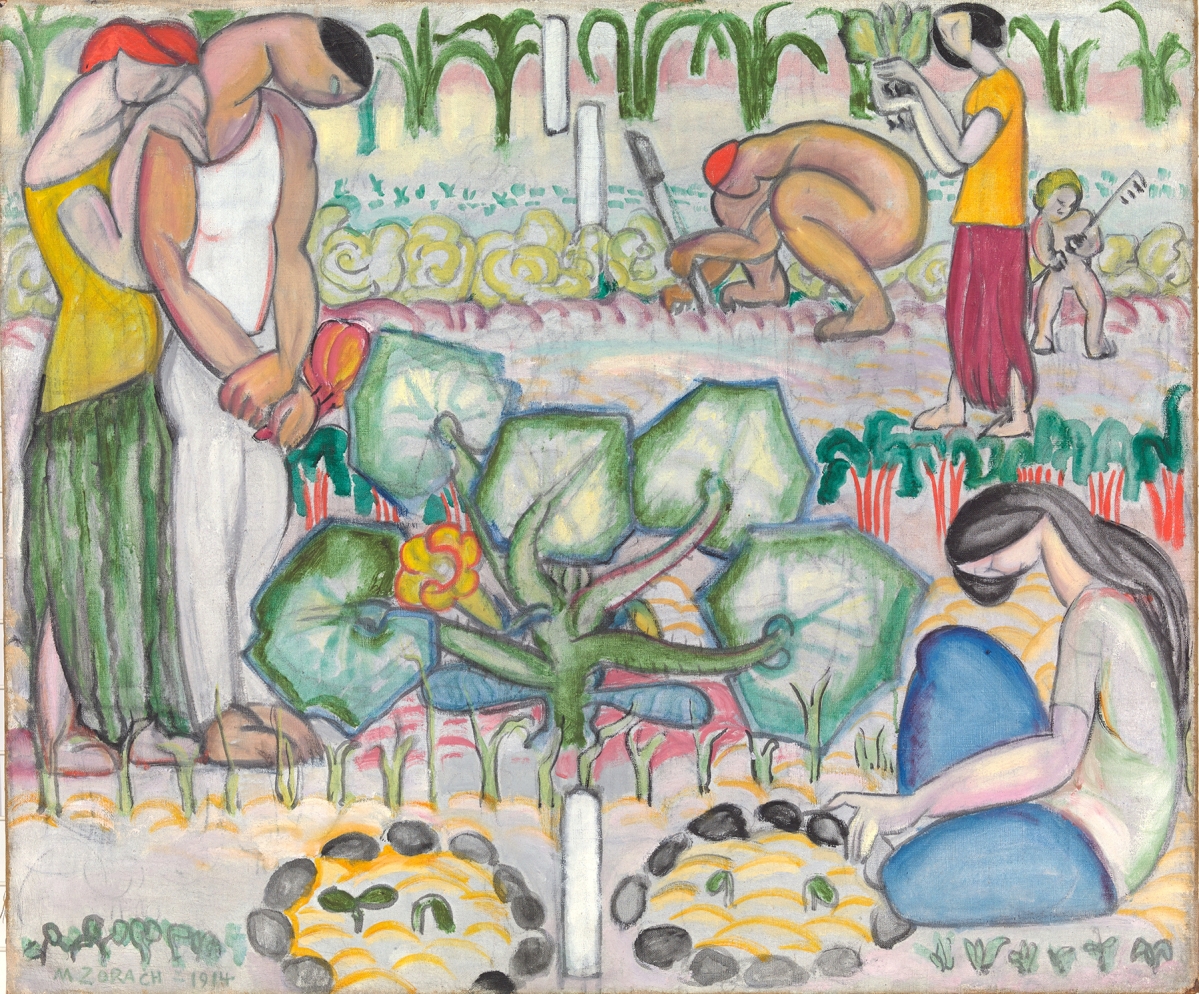

By Zorach’s own account, it was difficult to balance motherhood and artistic practice. A double portrait of the young Dahlov with her African American nurse, Ella Madison, suggests that it was in fact impossible without help. Nevertheless, Zorach clearly idealized her family and her home in her mind and in her art, seeing it as a kind of Eden filled with love and creativity. In researching the exhibition, Bianco persuaded Ipcar to reminisce about her parents’ much-loved Greenwich Village apartment and sketch a floor plan of it, reproduced in the catalog. Ipcar marked, on the left-hand wall of the entry hall, where her mother painted a life-size mural of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. The theme appears over and over again in Zorach’s work, especially from this period – in her magnificent painting “The Garden,” 1914, done during a summer spent in the country; in the watercolor titled “Adam and Eve,” 1920; and in “Two Nudes,” which places the theme in an urban setting, 1922.

The female nude is a major feature of Zorach’s work, with works like “Nude,” 1922, reflecting her interest in dance and stressing a kind of goddesslike female power. But she also depicted male nudes alongside them as often as not, frequently in her embroideries. Zorach had been creating and exhibiting embroideries and other textiles from the earliest days of her career, sometimes in collaboration with William. But she fully embraced the medium as her own after the birth of her children, observing that “it is work that can be picked up and put down…. It is not dependent upon consecutive time,” which would have been in short supply with two young children underfoot. Her embroideries – the example from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) is an iconic instance – frequently celebrate the intertwining of male and female, parent and child, and home, work and nature that was spiritual core of her art and her life.

Bianco marvels at Zorach’s skills and vision when it comes to embroidery, praising “the loving way she did the cloth, and the myriad details, and the invented stitches,” and observing how she used not only stitch variety, but also depth and weight to articulate, for example, a muscle in the thigh or the size of a figure’s big toe relative to the little toes or the loops around the handle of a tennis racket. The latter is from a monumental embroidery she did for John D. and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, whom she had met through art dealer Edith Halpert.

The female nude in an interior was a favorite subject of Modernists. This composition seems clearly influenced by Matisse, who also employed textile patterns in his paintings. Unlike Matisse, however, Zorach here has used not exotic Eastern textiles, but a Log Cabin quilt and needlepoint upholstery. “Nude,” 1922. Oil on canvas, 40¼ by 30 inches. Worcester Art Museum.All works are by Marguerite Zorach, unless otherwise noted. Photos courtesy Farnsworth Art Museum.

The piece, known informally as the Rockefeller Tapestry, is a portrait of their family (clothed, unlike many of her other portraits) at their estate in Seal Harbor, Maine. Within the landscape outside the grand home, family members each pursue their own unique interests, holding their tennis rackets and books and magnifying glasses as if they were “attributes of the saints,” in Bianco’s words. Bianco has made several new discoveries, detailed in the exhibition’s gallery labels, about both the MFA bedcover and the Rockefeller Tapestry.

Commissions like these were very lucrative, and for an extended period Zorach’s embroideries were thus the primary means of support for her family. It is regrettable that, when her husband’s career later began to take off, critics often used her success as a textile artist to relegate her to a category somewhere below that of “fine artist.” One way she circumvented this in the 1930s was by competing for commissions from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA), which in part sought to hire artists to create murals for federal buildings across the United States. Because the submission process was anonymous, Zorach’s work could be considered apart from either her gender or her increasingly famous surname. She won four commissions (though only three were installed), and the exhibition includes numerous studies, including some of her original proposals.

“Land and Development of New England,” while not specifically related to an individual mural, is typical of her work in this vein. She retained her long-familiar interests in nature and family while exploring agriculture and industry. New in these works is a kind of emerging Regionalist aesthetic, an interest in local and folk traditions and in the lives of so-called common people, rather than the mythologized bohemians and plutocrats that appeared in her earlier work. As always, the interests of her professional life and her domestic life intertwined. Around this time she also began filling her Maine home with hooked rugs, mochaware jugs and other antiques. She also covered the walls with hand painted and stenciled ferns, stars, nudes and every kind of living creature imaginable, all in yellow and green. The wall paintings (and many of the antiques) remain at the home today as a lasting example of her impulse to create and live in her own unique Eden.

Because landscape is the backdrop, if not the primary subject, for so many of these works, it is worth pointing out that Zorach often did paint pure landscapes as well. Works like “City of Bath,” 1927, “Woolwich Marshes,” 1935, and “Etang du Nord,” 1957, with their expanded palette and consideration of space, connect with landscapes she made late in her life during a 1960s trip out West, which in turn connect back to landscapes she made of California in the earliest phase of her career, before her marriage. Considering those earlier works, Bianco’s words seem almost prophetic. “I feel like she really takes off … she doesn’t worry about filling all the spaces on the canvas. She is starting to come into her own.”

In the Farnsworth exhibition, too, one might consider that Marguerite Zorach has come into her own – but to the extent that is true, it is only true in terms of public perception. Marguerite Zorach, as this exhibition beautifully confirms, did things her own way from beginning to end.

The Farnsworth Art Museum is at 16 Museum Street. For more information, www.farnsworthmuseum.org or 207-596-6457.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is the managing editor of Panorama: the journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She lives in South Portland, Maine.