An exhibition in Phoenix through July 28 offers a reappraisal of the pioneering American potter.

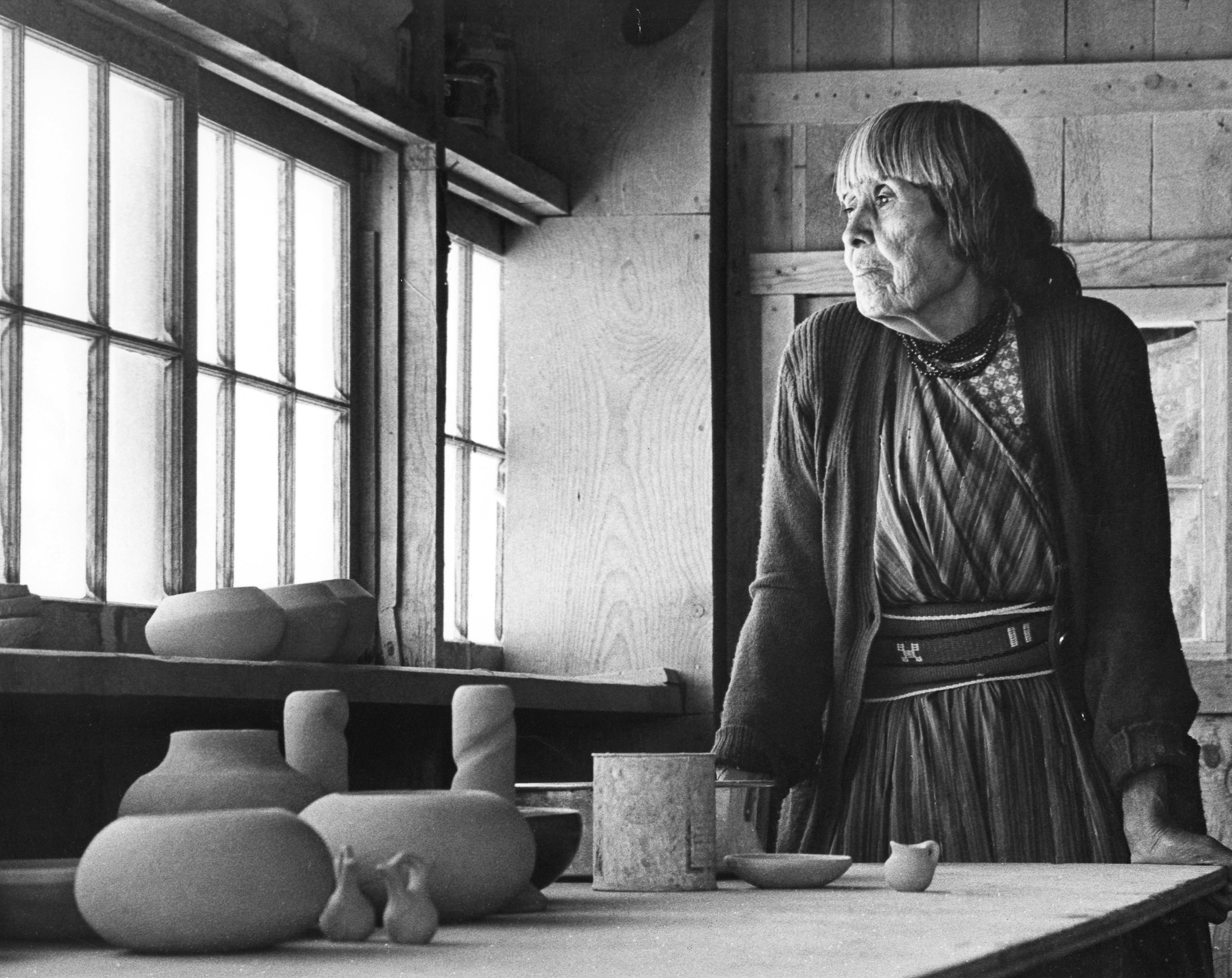

“Maria Martinez,” photograph by William H. Regan, about 1964. Courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Heard Museum (Susan Peterson Collection, Billie Jane Baguley Library and Archives, RC220(3):47.

By Laura Beach

PHOENIX, ARIZ. — It requires no special expertise to admire the graceful form and crisp, understated decoration of black-on-black pottery by Maria Martinez (1887-1980). With good reason, the artist from San Ildefonso Pueblo/P’ohwhogeh Ówîngeh has for more than a century enjoyed celebrity status, as readily identified with the arts of New Mexico as her contemporary, Georgia O’Keeffe.

Despite her wide fame, Maria — her success was such that she has long been known by one name — has yet to receive her full due, say curators at the Heard Museum, organizers of the visually compelling, intellectually provocative exhibition “Maria & Modernism,” on view through July 28. Countering old stereotypes, project principals David M. Roche, Diana F. Pardue and Roshii Montaño (Diné) present Maria, her traditional dress and devotion to family and community notwithstanding, as a technically innovative artist and savvy, well-traveled businessperson at home in the modern age.

Installed in the nearly 10,000-square-foot Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust Grand Gallery, “Maria & Modernism” draws from the Heard’s own collection and other public and private lenders to array roughly 100 ceramic objects by Martinez and her collaborators and successors, plus Modernist paintings and archival photographs and documents, some new discoveries among them. The exhibit and its accompanying catalog are the latest in a series of projects at the Heard placing Native American creativity within the broader scope of American art. Co-curator Montaño cites the recent traveling exhibition “Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe” as one example of the surging interest nationally in Native Modernists, observing that women artists such as Maria remain particularly understudied in this realm.

“Rose B. Simpson’s ‘Maria’” by Kate Russell. Photograph of the 1985 Chevrolet El Camino that Santa Clara Pueblo artist Simpson customized in 2014 with designs inspired by traditional Tewa black-on-black pottery by Maria Martinez (1887-1980). Photo courtesy Kate Russell.

Maria’s first pieces, which predate her marriage to Julian Martinez (1879-1943) in 1904, are typical for their time, employing San Ildefonso Pueblo’s earlier polychrome palette. Pottery making was a shared activity in Pueblo communities, with women forming pots often decorated by others. In keeping with tradition, Maria over her long career collaborated with a succession of family members. Besides her husband, her artistic partners included her son Popovi Da; son and daughter-in-law Adam and Santana Martinez; and grandson Tony Da. Admired for his skillful, imaginative decoration, Julian was essential to the couple’s early success, even if their pots were at first simply inscribed “Marie.”

The world came to know Maria — and Maria, the world — through expositions, foremost among them four world’s fairs. The newlyweds participated in the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, called the St Louis World’s Fair, in 1904, and were part of the Panama California Exposition, which opened in January 1915. “It was around this time that Maria began making some of her first exceptionally large pieces. Their shapes were inspired by the work of earlier San Ildefonso Pueblo potters but had a new sophistication of form, with rounder shoulders, short necks or sloping sides. Her pottery became perfect ‘canvases’ for Julian,” writes catalog contributor Charles S. King.

Black-on-black jar by Maria and Julian Martinez, circa 1940, 17 by 22 inches. Philbrook Museum of Art, gift of Clark Field, 1946.46.1.

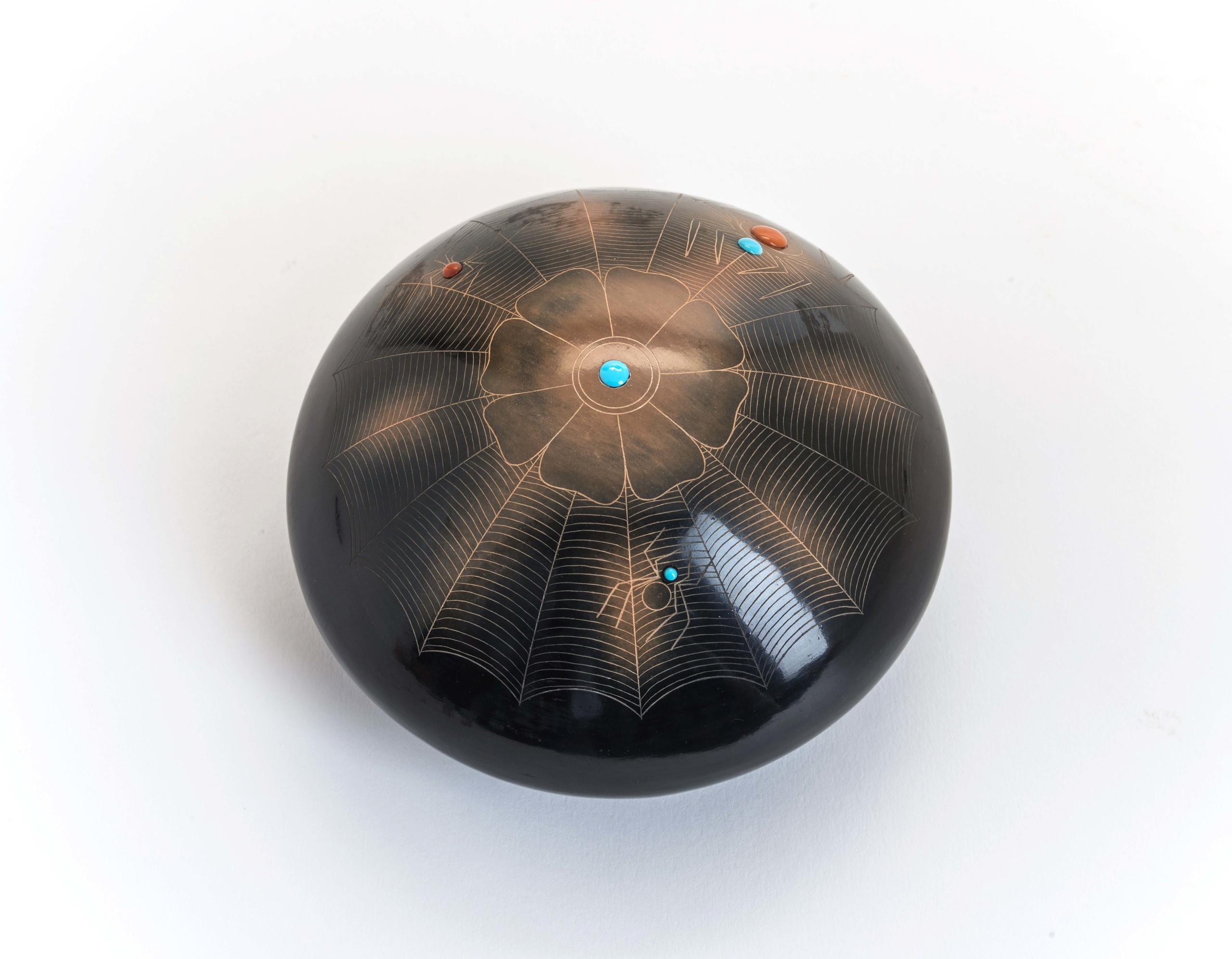

The couple’s major breakthrough — the development of their signature matte black designs on a lustrous black ground — occurred around 1919 after a decade of experimentation, a date suggested by the Museum of New Mexico’s acquisition of a black-on-black ware piece by Maria in 1920. Black-on-black pottery soon dominated San Ildefonso Pueblo production. As described in detail by catalog contributor Cody Hartley, the couple, in part inspired by pre-historic shards, achieved a dull black finish by smothering the fire. Julian then perfected a fine paste mixed with guaco. Brushed on previously polished pottery, it left a matte finish when fired. Maria grew ever more skillful at shaping her hand-coiled vessels, which she then hand-polished with stones. Her pots, jars, vases and plates are decorated with stylized depictions of the avanyu, or water serpent; rain clouds; and eagle feathers, among other favorite motifs.

“From the time she began producing her innovative black-on-black ware, Martinez’s pottery was sought-after by major artists, collectors and thought leaders. She once quipped in reference to her pottery that ‘black goes with everything,’” writes Heard Museum director David M. Roche, who observes parallels with the monochromatic paintings of Yves Klein and cites “Black-Black,” an abstract canvas of 1950 by Leon Polk Smith (1906-1996), an artist who spent several months in Santa Fe in the mid-1940s on a Solomon Guggenheim scholarship.

Black-on-black jar by Maria and Julian Martinez, circa 1930, 9 by 10½ inches. Private Collection.

Buyers of Maria’s work included photographer Ansel Adams and, intriguingly, John D. Rockefeller Jr, and his wife, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, the latter a prominent champion of folk and Modern art. Their sons David and Laurance in tow, the Rockefellers in 1926 visited San Ildefonso Pueblo, where they met Maria and purchased ceramics. The Museum of Modern Art, an institution Abby helped found, included Maria’s pottery in its 1941 exhibition “Indian Art of the United States,” a display Roche calls “a defining moment in the evolution of critical and scholarly thinking about American Indian creative expression.”

Northern New Mexico in the first half of the Twentieth Century was a place of unlikely cultural juxtapositions, some of them assiduously engineered by the social figure Mabel Dodge Luhan, who hosted everyone from D.H. Lawrence, Willa Cather and Aldous Huxley to Marsden Hartley and Georgia O’Keeffe at her compound in Taos. Organizers of “Maria & Modernism” marvel at the paradoxical proximity of San Ildefonso Pueblo, a centuries old community steeped in tradition, and Los Alamos, a purpose-built center for advanced scientific research and a symbol of the atomic age, just 12 miles of away. But as viewers of last summer’s blockbuster film Oppenheimer will know, Los Alamos is where it is less by chance than by design. Still, photographs from the archives of the Los Alamos Historical Society showing Maria in the delighted company of physicists such as the Nobel Prize winner Enrico Fermi are, then and now, enchanting reminders of New Mexico’s rich cultural milieu.

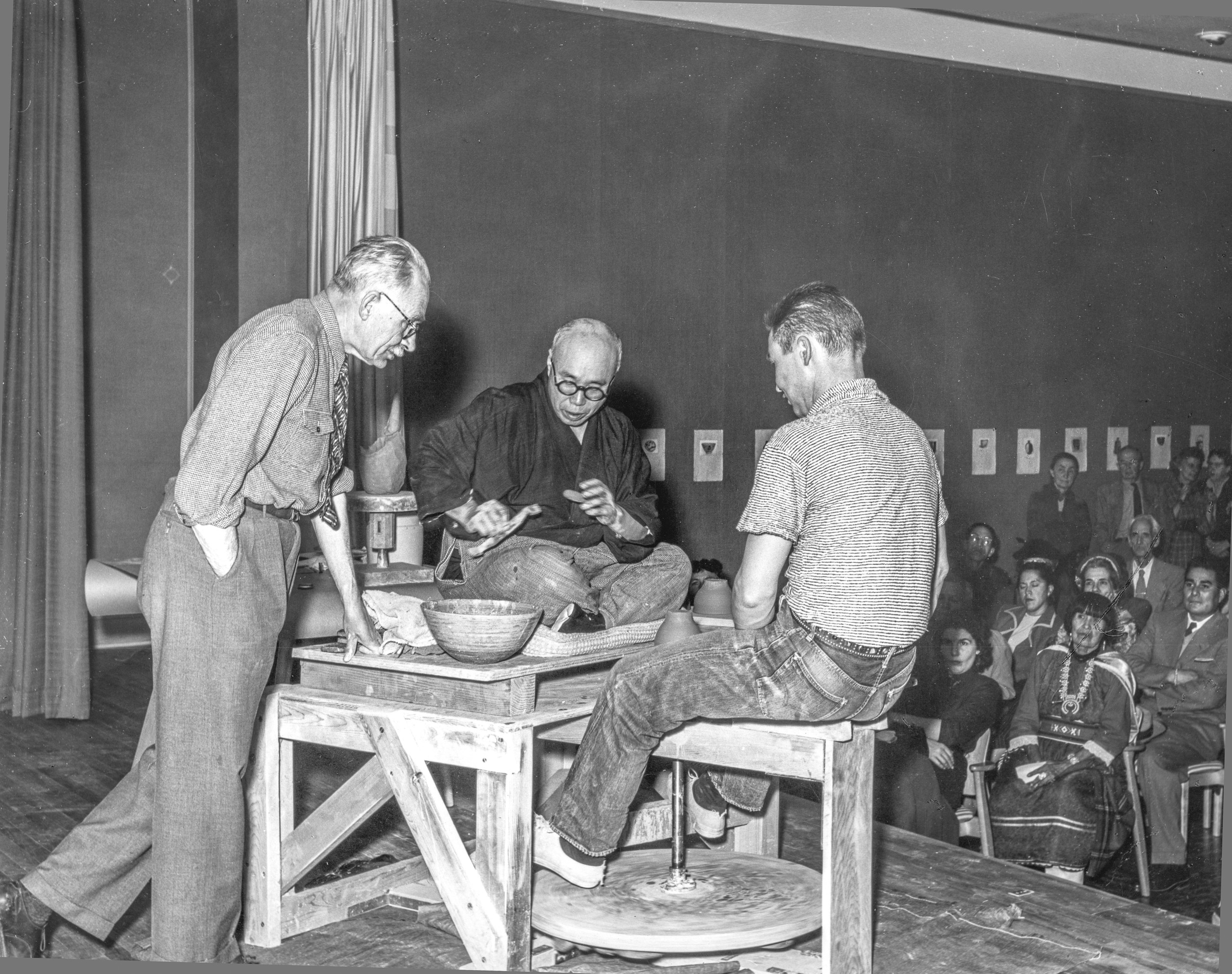

In this photograph taken in Santa Fe in 1952, Maria Martinez and Popovi Da, seated front right, observe a demonstration by Bernard Leach (1887-1979) and Shoji Hamada (1894-1978), fathers of the studio pottery movement. Standing against the wall is Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986). Heard Museum (Susan Peterson Collection, Billie Jane Baguley Library and Archives, RC220(3):44).

Beyond style and technique, Maria’s most enduring contribution is her role in enlarging and perpetuating a vibrant artistic tradition. The exhibition concludes with a passing mention of other “matriarchs” — Margaret Tafoya, Severa Tafoya, Sara Fina Tafoya and Rose Naranjo, among them — before offering works by several of Maria’s descendants, among them potters Barbara Gonzales (b 1947) and her son, Cavan Gonzales (b 1970) and filmmaker Charine Pilar Gonzales (b 1995), whose short documentary Our Quiyo: Maria Martinez (2022) premiered at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and may be seen at the Heard.

“Another part of Maria’s legacy is her innovation and experimentation, her desire to keep working toward something new while also having reverence for the past,” observes Montaño, who writes that contemporary Tewa artists reject “antiquated conceptions of how and what Pueblo pottery should be.” As proof, “Maria & Modernism” arrays pieces by, among others, Russell Sanchez (b 1963) — a master potter from San Ildefonso Pueblo who embellishes his vessels with sgraffito and inlay — and a host of Santa Clara Pueblo talents, among them Tammy Garcia (b 1969), known for her carved clay vessels; Jody Fowell (b 1942), whose supremely elegant jars offer a thoroughly contemporary take on Maria’s minimalism; and Ty Moquino (b 2002), whose 2022 sculptural form “Journey” levels stark social criticism.

The exhibition is accompanied by a handsome catalog featuring scholarly essays placing Maria Martinez within the broader story of American art, design and culture in the Modern era.

The catalog Maria & Modernism is both elegant keepsake and essential reference. In addition to Roche, Pardue and Montaño, its eight contributors include Betsy Fahlman, a professor of art history at Arizona State University and an adjunct curator at the Phoenix Art Museum; Cody Hartley, director of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, N.M.; and Charles S. King, a scholar of Native American pottery and founder of King Galleries in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Essays by Charine Pilar Gonzales and Rose B. Simpson (b 1983) offer the most intimate look at Maria and her legacy. Gonzales writes, “There are many biographies and stories shared about Maria. Still, the most truthful perspective comes from our Pueblo people, who learned from and knew Maria — our family. It is through the stories shared by six generations of traditional pottery artists that Maria’s legacy lives on today. I’m so grateful to have grown up hearing stories of Maria, our Quiyo.”

Simpson sums up “Maria & Modernism” with the most elan. A mixed-media artist from Santa Clara Pueblo / Kah’p’oo Ówîngeh whose work is featured in the 2024 Whitney Biennial, Simpson transformed a 1985 Chevy El Camino by painting it matte black with glossy black designs. In profile, the car’s flat-topped silhouette evokes nearby Black Mesa, a volcanic plateau held sacred by Pueblo Indians. Simpson’s stylish tribute to Maria is worthy of the bold, brilliant woman who took the art world by storm.

The Heard Museum is at 2301 North Central Avenue. For more information, 602-252-8840 or www.heard.org.