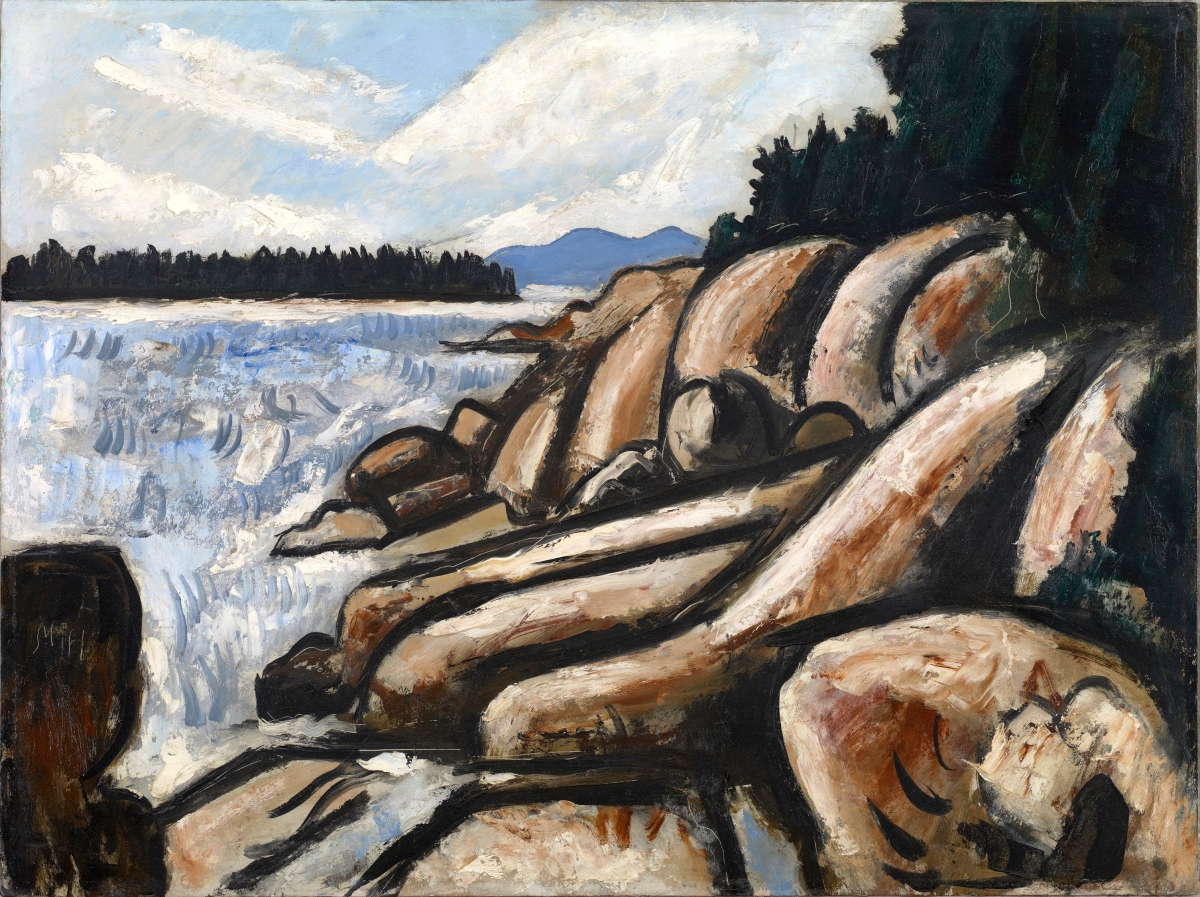

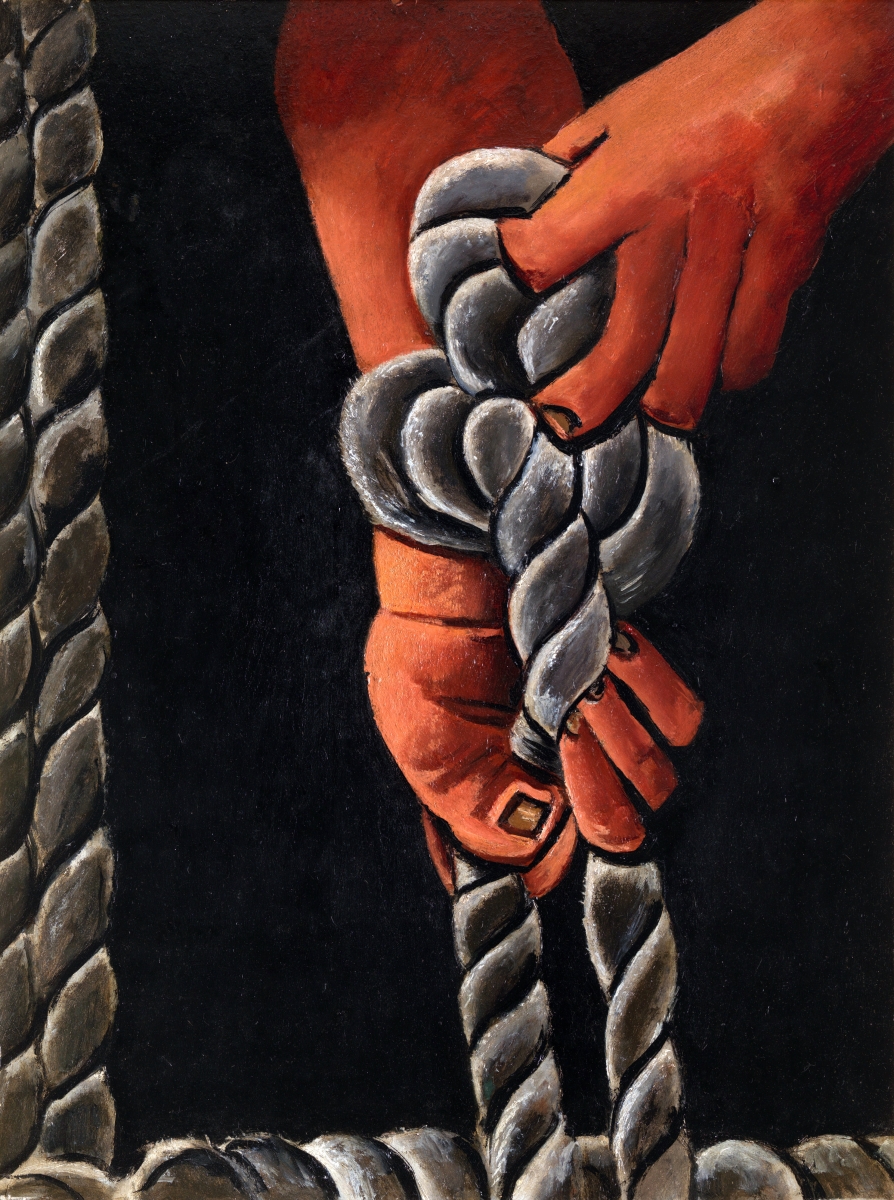

“City Point, Vinalhaven,” 1937–38. Oil on commercially prepared paperboard (academy board).

Colby College Museum of Art

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

NEW YORK CITY – Every Art 101 student knows Marsden Hartley for his vibrant, highly Modernist, symbolic portraits: Gertrude Stein as a cup of coffee, as resplendent as a Mexican altar; his friend and possible lover Karl von Freyburg as a patchwork of emblems representing the German army. Such works seem to exemplify a pinnacle of American Modernism – cosmopolitan, abstracted, global in their influences.

But the current Hartley exhibition at the Met Breuer sets those iconic paintings aside, arguing persuasively that Hartley’s home state of Maine – more so than Paris, Berlin or even New York – was the touchstone for his career. Organized by curators Randall Griffey of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Elizabeth Finch of Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine, with University of Southern Maine professor Donna M. Cassidy, “Marsden Hartley’s Maine” remains at the Met Breuer through June 18 before traveling to Colby, where it may be viewed July 8-November 12.

“The painter from Maine” was an identity that Hartley consciously cultivated for himself, particularly later in his career. He spent years in the art capitals of Europe, where he was inspired and influenced by Paul Cezanne and others, but was always drawn back to Maine. Whenever he returned, he was heralded as a kind of prodigal son, at last back where he belonged and where his art could be authentically “American.” By 1937, when he began to live in Maine more or less full-time, he was fully complicit in this mythmaking, as his seascapes and views of Mount Katahdin found their way into major museum collections and seemed to cement his legacy as Maine’s premier painter of place.

Hartley would surely have been surprised, then, to see the so-called German Officer paintings dominate his reputation for a generation or more. Hartley died in 1943, just before the advent of Abstract Expressionism. He could not have anticipated that most midcentury critics would deride any Twentieth Century art that did not seem to look forward to pure abstraction. There was no room in the history books anymore for works like the seemingly traditional “The Wave,” purchased by the Worcester Art Museum in 1941, or “Lobster Fishermen,” acquired by the Met in 1942.

Hartley would surely have been surprised, then, to see the so-called German Officer paintings dominate his reputation for a generation or more. Hartley died in 1943, just before the advent of Abstract Expressionism. He could not have anticipated that most midcentury critics would deride any Twentieth Century art that did not seem to look forward to pure abstraction. There was no room in the history books anymore for works like the seemingly traditional “The Wave,” purchased by the Worcester Art Museum in 1941, or “Lobster Fishermen,” acquired by the Met in 1942.

Much has already been done to reestablish Hartley as more than just a one-note artist. Barbara Haskell’s retrospective at the Whitney in 1980 was the first of several major museum exhibitions to examine the full range of his career. However, not since then has a major Hartley exhibition been presented in New York City. Further, while these previous shows admirably demonstrated the range of Hartley’s interests and output, none placed Maine in the foreground in the same way the present exhibition does. Notably, the show occupies the same space, now under different management, as the 1980 exhibition.

But what are we to do with this idea of Hartley as a “Maine artist”? Alone among nearly all artists of international stature, Hartley was actually a native of the state. He was born in 1877 in Lewiston, a textile-mill town on the Androscoggin River, and lived there until the age of 16, when he moved with his family to Cleveland, Ohio. Only after pursuing his artistic studies there and in New York for seven years did Hartley elect, as so many young artists did at the time, to spend a summer in Maine.

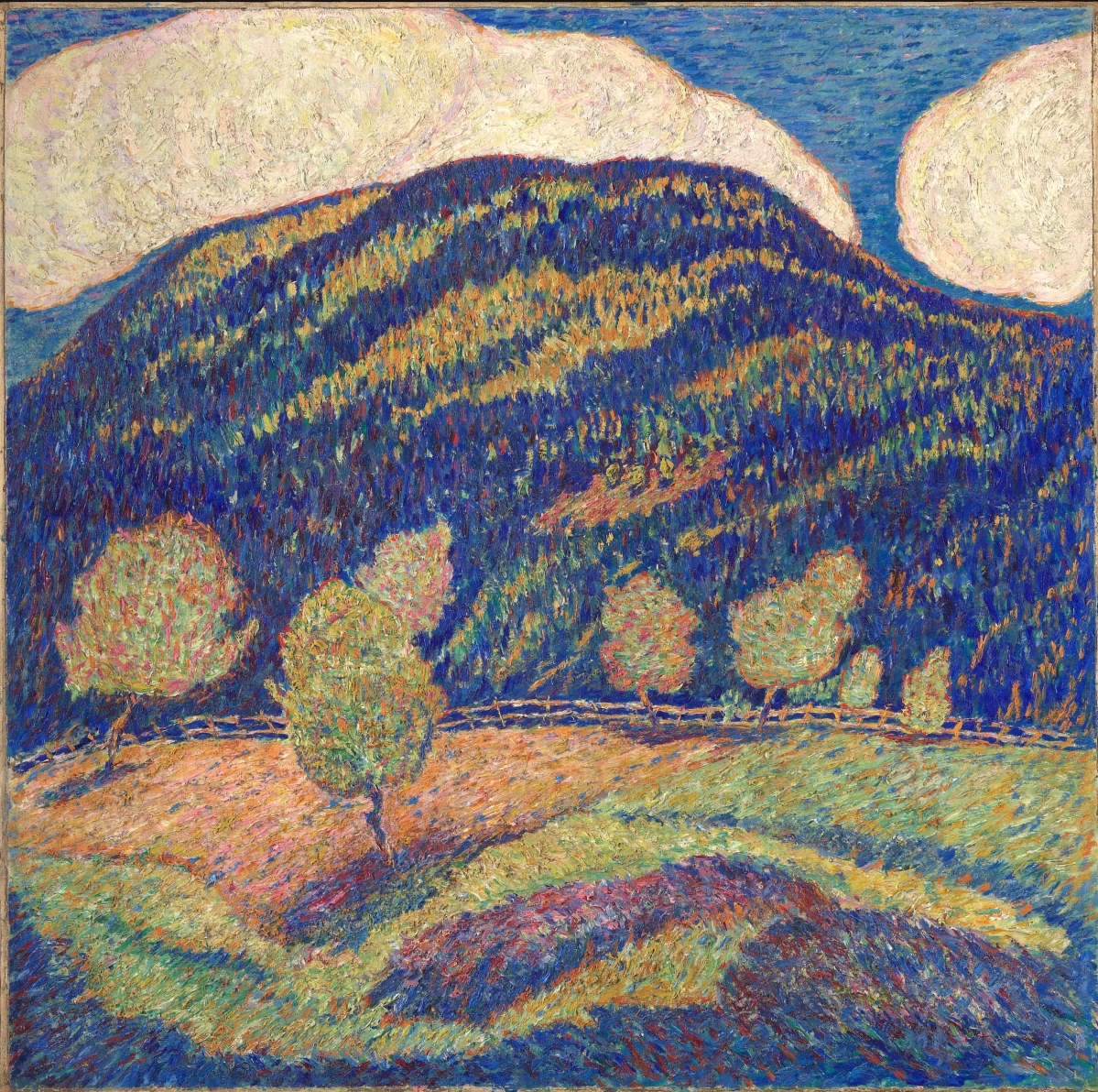

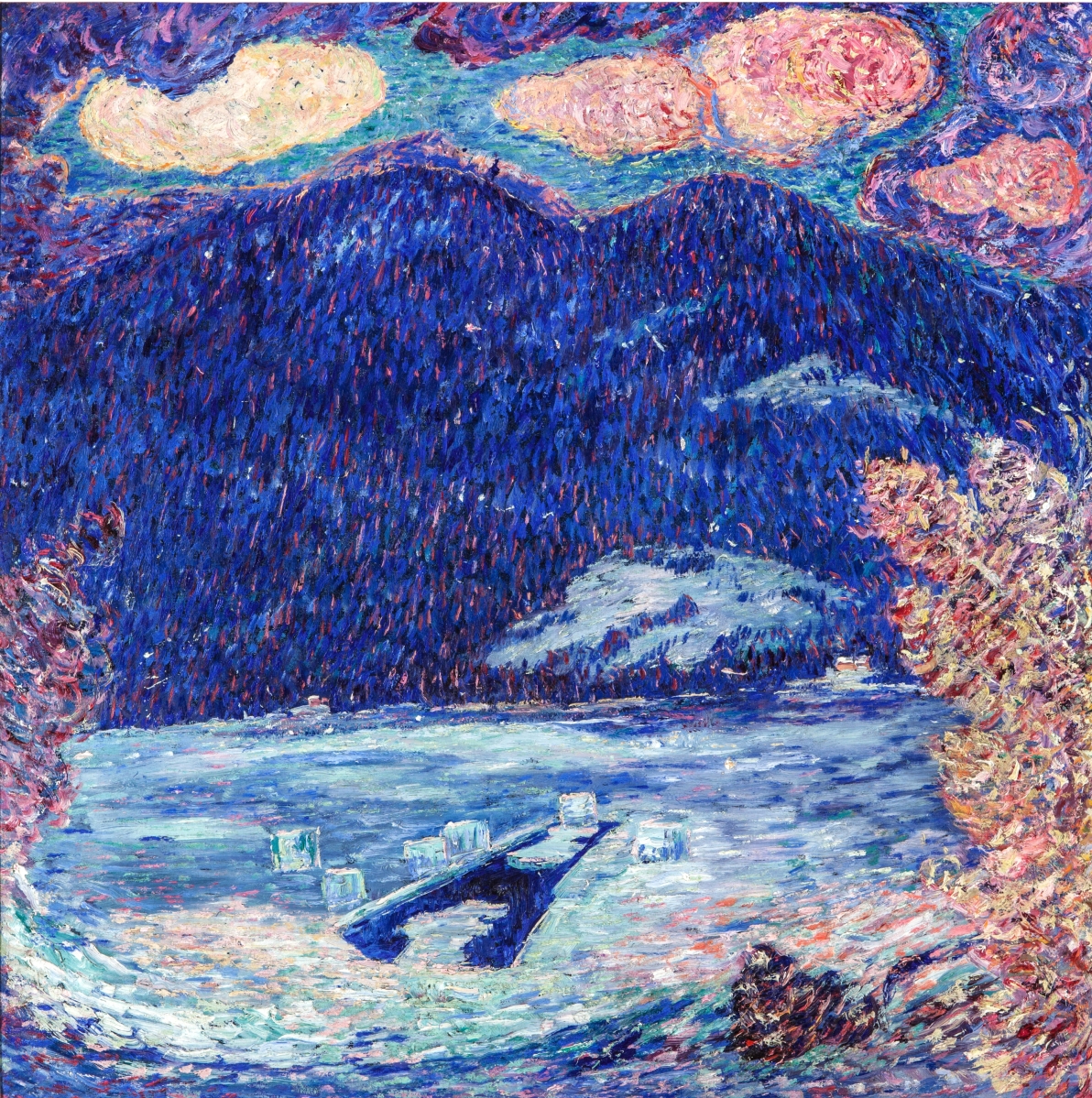

Finding that Lewiston’s urban landscape did not match the Maine of his memory or imagination, Hartley turned instead to Maine’s quietly spectacular western mountains, an area he visited regularly for the next decade or so. Works like “The Silence of High Noon” and “The Ice Hole” capture with astonishing fidelity the colors, the clarity and the sense of space and eternality in that aged interior landscape. There is no denying their authenticity. Yet Hartley, despite his credentials as a Maine native, was a newcomer to that part of the state.

“Hartley would have liked his audience to think that because he was born in Maine he was going to paint the ‘real’ Maine,” says Cassidy, “but I have argued that he really is an outsider returning to Maine with a vision that has been shaped by other places, other artworks.”

Those early paintings brought him to the attention of dealer Alfred Stieglitz and gallery owner E.N. Montross, who introduced him to the dark and visionary work of earlier American master Albert Pinkham Ryder. Responding to such influences, Hartley entered what is known as his “Dark Landscapes” period, characterized by broadly painted works such as Untitled (Maine Landscape) and “Desertion.” In her catalog essay, Finch situates the meaning of these works between Hartley’s longing for Maine as an artistic and spiritual home and his fundamental restlessness and “pattern of leave-taking.” “[Maine] was a place to be remembered, imagined and revisited from afar. … Hartley lived as an observer, always at a conscious remove, connecting at a distance.”

That distance widened between 1912 and 1916, when Hartley was in Europe. There he created those iconic, symbolic portraits so celebrated by midcentury critics and historians. But he also learned the German craft of hinterglasmalerei, or reverse painting on glass, which he later married to American folk art in works like “Three Flowers in a Vase,” painted upon his return stateside for a summer at Maine’s Ogunquit art colony. During a longer stay in France in the 1920s, Hartley revisited Cezanne in part by creating and exhibiting memory paintings of Maine mountains, realized in Cezanne-inspired bright planes of color.

Hartley spent much of the 1920s and 30s traveling. During this time, Cassidy says, artistic tastes in America had grown increasingly “internally focused, nativist.” When Hartley returned to first New York and then Maine in 1937, she observes, he was “out of sync with it.” This was the moment when Hartley, motivated not only by his sustained interest in Maine as a subject but also by his ambition to carve out a niche for himself as a great American artist, doubled down on his identity as “the painter from Maine.”

“Canuck Yankee Lumberjack at Old Orchard Beach, Maine,” 1940–41. Oil on Masonite-type hardboard. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution

Griffey, whose catalog essay examines Hartley’s work from 1937 until his death, acknowledges that there was a kind of strategic design to the trajectory of his career. “To some extent he did kind of acquiesce to pressure he felt to associate with the region,” he observes, “[but] I do think he in a way makes it his own.” Certainly, Hartley made Maine his own through his distinctive, mature style, visible in, for instance, “Colby’s City Point, Vinalhaven”: simple, recognizable, roughly painted forms outlined in black. Finch notes that the Met’s paintings conservators, who also contributed an essay to the catalog, discovered a fingerprint in the clouds of “City Point,” and that “it doesn’t seem like a mistake.” So Hartley was, in a very literal sense, making his mark on the Maine landscape.

But Hartley painted far more than landscapes in this latest phase of his career. Mixed in with the mountains, waterfalls and crashing surf, his logjams, still lifes, bird portraits and depictions of nearly nude male bathers break open the paradigm of “Maine art.”

Paintings like “Canuck Yankee Lumberjack at Old Orchard Beach, Maine” and “Madawaska-Acadian Light-Heavy” are particularly perplexing to modern eyes. Are they meant to ridicule? French Canadians in Speedos remain a perennial feature of Old Orchard Beach, where they are not always welcomed by the locals. Are they meant to be objects of desire? Hartley was, famously, gay, and there is an unignorable physicality to these works that borders on eroticism. Or, worryingly, are they meant to promote some sort of race-based ideal? Hartley wrote with some detail in his essays, poems and correspondence about his interest in eugenics, a theory that the races could be improved through selective breeding, and his fascination with what he saw as a “Yankee race” that should be preserved.

Finally, once again, there are the mountains. Griffey connects Hartley’s late-career engagement with Mount Katahdin to his awareness of Cezanne’s centennial in 1939, when the Modernist giant’s reputation became ineluctably linked to Mont Sainte-Victoire. It is exactly at this time that Hartley writes to a friend of Katahdin, “I must get that Mt. for future reason of fame and success.”

He did indeed make the mountain his own – there are no fewer than nine major Katahdin works in the exhibition – and in doing so he reenacted his earliest sustained work in Maine, when he returned to the western mountains year after year. All the mountain paintings are highly abstracted, and the late ones look very different from the early ones. Even so – raw professional ambition notwithstanding – a work like “Mt. Katahdin (Maine), Autumn #2” radiates the same authentic, lived experience of place as “The Silence of High Noon,” painted some 33 years earlier.

“The permanence of mountains touched him deeply,” notes Finch, arguing that his pursuit of mountains as a subject is analogous to “his own search for recognition and of legacy for his art.” Hartley’s relationship to the Maine mountains, then, is a synecdoche for his relationship to the state as a whole – his native land, his artistic touchstone, his home as much as he ever had one and the place where his legacy both took flight and came to rest.

The Met Breuer is at 945 Madison Avenue. For information, 212-731-1675 or www.metmuseum.org.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is a writer, editor and independent art historian in South Portland, Maine.

.jpg)

_autumn_2.jpg)