Paul Messier, chair, Yale Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage, Pritzker director, IPCH Lens Media Lab. —Jon Atherton photo

The presses could not be stopped in time to reflect Martina Droth’s promotion. The deputy director of research, exhibitions, and publications and curator of sculpture at the Yale Center for British Art, as she was identified on the dust jacket of Bill Brandt|Henry Moore, which she co-authored with Paul Messier, is now deputy director and chief curator. Messier is director of the Lens Media Lab at the Yale Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage. Their book is a close examination of the work, relationship and shared influences of the two masterful Twentieth Century artists, and they sat down with Antiques and The Arts Weekly to put their project, which has been shortlisted for this year’s Aperture PhotoBook Award, in focus.

Martina, before we dive into the book, congratulations on your promotion. What’s involved with this new position?

Thank you. My new position provides oversight and leadership to the curatorial work of the center. I oversee the center’s three collections departments – paintings and sculpture; prints, drawings and photographs; and rare books and manuscripts – as well as exhibitions, publications and the Registrar and Installation department. I am excited to work with my colleagues at this pivotal time for the museum on developing an innovative and compelling artistic program for the museum that realizes the full potential of our outstanding collections.

What were the circumstances that first brought together Henry Moore (1898-1986) and Bill Brandt (1904-1983)?

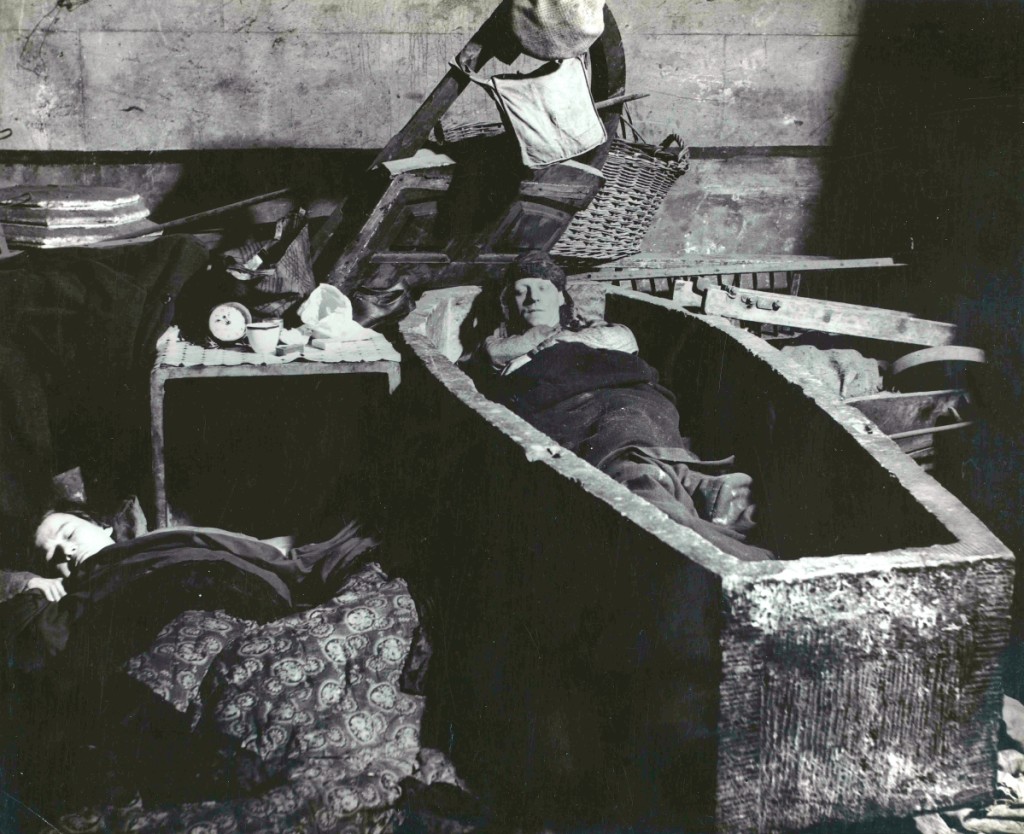

Brandt and Moore were first brought together by the circumstances of the Second World War. During the Blitz of 1940, both artists produced images of civilians sheltering in the London Underground at night. The first portrait that Brandt took of Moore in his studio was published in Lilliput magazine in 1942. The portrait was used as a frontispiece to a photo-story that juxtaposed Henry Moore’s drawings and Brandt’s photographs of the underground shelters. Their images bring out the uncanny tomb-like conditions of the underground tunnels that had been turned into makeshift domestic shelters. These dark, atmospheric images continue to define the civilian experience of the war in our visual imagination.

Is there a harmony between the sculptor’s imagination, the photographer’s eye and the printed page?

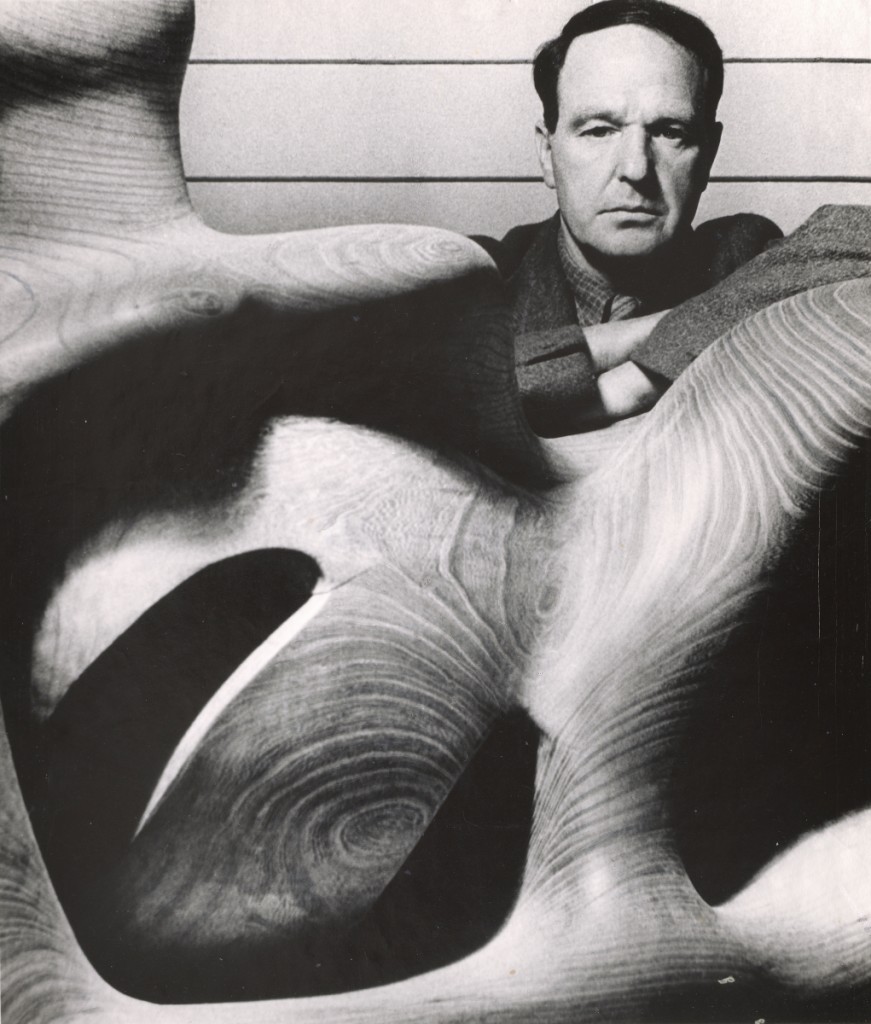

Photography is the medium that brings the two artists together. The project explores the distinct ways in which Brandt and Moore responded to their time and place, and the pictorial possibilities of their contemporary world. Brandt was a photographer who looked to sculpture as a subject and as a way of reimagining nature and the human body, while Moore was a sculptor and draftsman who made a serious commitment to photography, not only as a means to record and disseminate his work but as a creative medium in its own right.

There is an exhibition to which this book is a companion. On view at Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich, November 21-February 28, 2021, when does it come to the Yale Center for British Art?

The exhibition was developed by the Yale Center for British Art in partnership with the Hepworth Wakefield, where it has just been on view. After its presentation in Norwich it will open at the Yale Center for British Art on April 15, 2021, through July 18.

How closely tied to the book is it?

The book and the exhibition closely relate to each other, but they each create a distinct experience. The narrative begins with the wartime works – the underground shelters and the blackout, the coal mines – which are set within the visual culture of the war. We then examine the parallel and intersecting paths of the artists through the postwar period, with key themes touching on war, industry, steel and coal mining, landscape and the great megalithic sites of Britain, found objects, fragments of nature and the human body. The exhibition and the book feature a number of works that have never been published before.

In the book, we wanted to recreate a material experience of the works. Unusually for a book of this kind, we have included a wide array of works that are often considered peripheral or secondary: newsprint, magazines, negatives, contact sheets, cutouts and unfinished experiments in collage are placed on equal footing as sculptures, drawings and photographic prints. The book takes a distinctive approach to the reproduction of photographic works, capturing the materiality of the print as a singular, three-dimensional object rather than a flattened image on the page. Beautiful illustrations of the artists’ works are shown alongside pages from popular period magazines such as Life and Picture Post.

Bill Brandt, “East End Crypt Shelter. Man Sleeping in a Coffin,” 1940, gelatin silver print,

Hyman Collection, London, ©Bill Brandt/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

What were the respective strengths that each of you brought to the project?

[MD]: I am a historian of sculpture and have curated many exhibitions that explore sculpture’s relationship with other media and practices. Sculpture and photography have been closely intertwined with each other since photography’s very beginnings in the mid-Nineteenth Century. I have long been interested in the way that modern sculptors have used photography in strategic ways, both as a creative medium and as a means to disseminate their work. [PM]: I am a conservator of photographs with an interest in the material history of photography, particularly photographic papers. Interest might be an understatement – over 20 something years, I assembled a reference collection of Twentieth Century photographic paper, maybe the largest in the world and now held by Yale. This work grounds my understanding of photographic printing, helping me interpret the expressive aims of photographers. For Brandt, the relationship to the print as both object and image is quite intimate and intense. The challenge of conveying this relationship infused the project with the idea that a photograph, like a sculpture, exists in three dimensions. The book’s innovative illustrations of Brandt’s prints are the clearest articulation of this idea, and I think set a new standard for the reproduction of photographs.What did Moore mean when he said, “most people, I think, respond more easily and quickly to a flat image than to a solid object”?

Moore made this comment in the context of Mesopotamian art in an article he wrote in 1935. In it, he acknowledges the important role of illustrated books as a means of introducing people to sculpture. He believed that “in illustrated books on sculpture, the photographs should be the best possible and well reproduced, or the book loses half its value.” He recognized that photography was relatable, and that it provided a means for a larger audience to discover sculpture – but to do so, the photographs needed to be compelling. Moore pointed out that photographs of tiny Mesopotamian artifacts made the objects appear huge – but he was not troubled by this distortion. On the contrary, he believed that “it is legitimate to use any means which help to reveal the qualities of the work.” This reflects his own practice of setting up small models and photographing them from a low angle against the skyline so that they looked monumental.

Bill Brandt, “Henry Moore,” 1948, gelatin silver print, Hyman Collection, London, ©Bill Brandt/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

How large is the photographic archive at the Henry Moore Foundation and to what use did he employ the prints and negatives?

Henry Moore’s photographic archive is preserved at the Henry Moore Foundation and comprises more than 200,000 items. His deep and sustained engagement with photography has barely begun to be examined. He was particular about how his sculptures were set up in front of the camera to create a sense of monumentality. He took a lot of photographs himself and also worked closely with photographers on how to capture his work. If you look at early exhibition catalogs – for example the 1946 catalog of his show at MoMA in New York – you can see that much of the photography of the sculpture was Moore’s own; in other words, he was able to control and orchestrate the way his work was disseminated. Moore also used photographs as an art material for collages. The exhibition includes a number of finished and unfinished works that collage together cut up photographs of found objects, such as flint stones and shells, and combine them to create sculptural figures in landscapes.

As a photographer, to what extent did Brandt intervene in the reproduction of his prints in the book printing process?

From the start of the project, we were taken with how Brandt is strongly present in his prints. For Brandt, making the print often was just a step toward eventual publication – culminating with the image rendered as ink on paper. Given this intermediate status, Brandt freely worked the surface of his prints – adding media, whether pencils, dyes, ink, gouache, but also surgically altering the image with a blade. These interventions are readily visible on Brandt prints, making each print a singular expression. Of course, Brandt knew this surface work would not be visible when the image was reproduced. For much of Brandt’s career, publication in the popular press or through his own books was his principal goal. In our writing for the book, we assert this relationship between the photographic print and the printed page established a feedback loop that is essential for understanding Brandt’s development as an artist. For example, the graphic simplicity of his late-career photographic printing is evocative of the effect of transforming a photographic image into ink on paper with its resultant compression of tonal range, increase of contrast, and loss of detail especially in the highlights and shadows.

-W. A. Demers

[Editor’s note: Bill Brandt | Henry Moore, edited by Martina Droth and Paul Messier, published by Yale Center for British Art, 2020; 256 pages, 269 color illustrations, $65/£50 hardback].