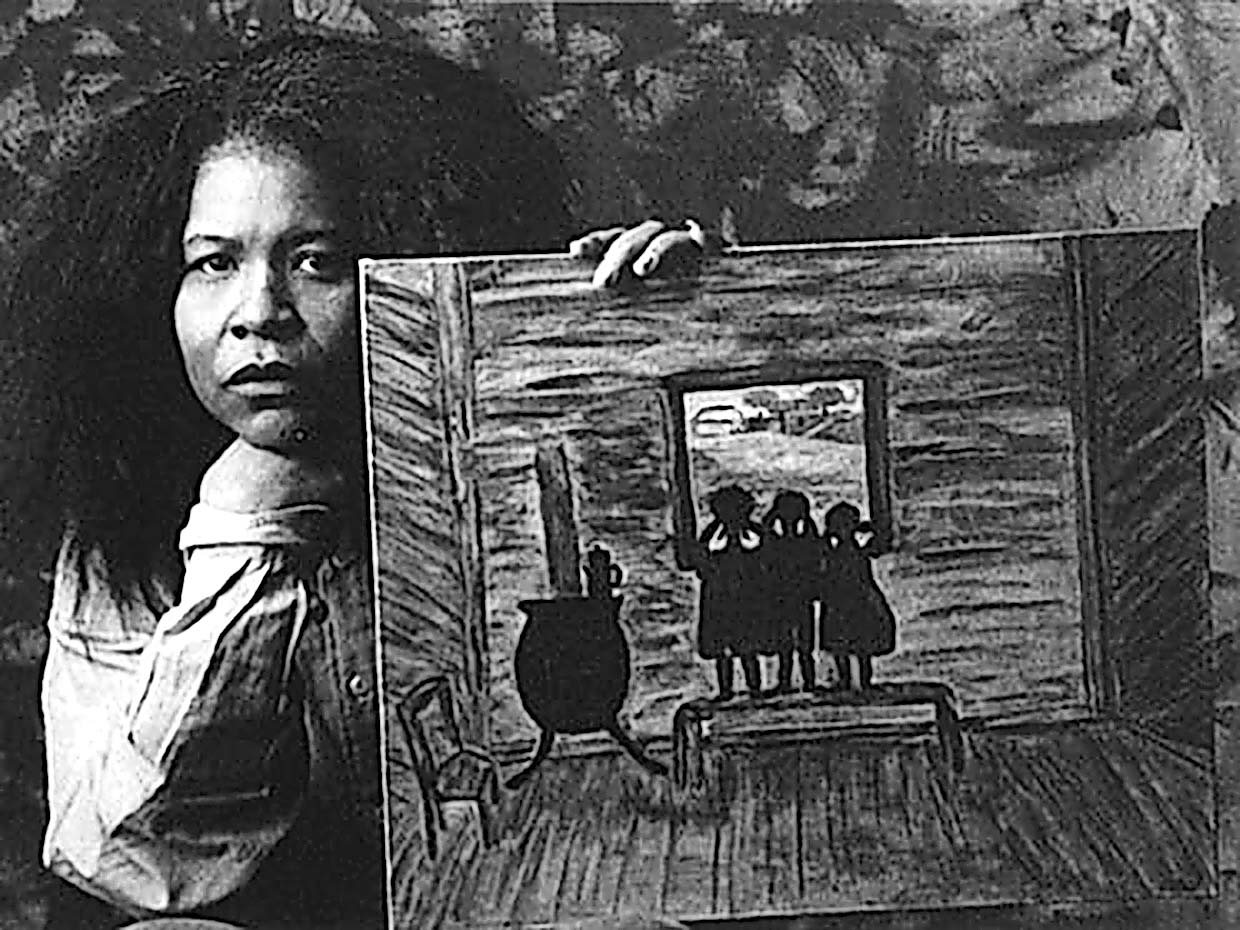

Kerry Kehoe photo, n.d.

Submitted by Phyllis Stigliano

CANTON, OHIO — Over the past 30 years, self-taught artist Mary Frances Whitfield gained recognition for her small, mythic watercolors depicting America’s tragic legacy of slavery in the South. Born in 1947, in segregated Birmingham, Ala., Whitfield would listen to her grandmother’s stories which lead to her determined focus on slavery throughout her artistic career, even at a time when her ancestors did not want to be reminded of their past.

Her oeuvre of faceless figurative allegorical works of real themes began in 1989. Her inspiration came — not only from her passionate remembrances of her Black ancestors as seen in her small and only surreal work, “My Ancestors’ Blood Cry From the Earth” (circa 1995) — but from her personal visions. Her first solo exhibition took place in 1991 at Sea Cliff Gallery, N.Y. In a review of the show, art critic Margaret Moorman wrote in Newsday, “ …Artists who move us are terribly rare. Whitfield is one. It will be exciting to watch her development, not just over the years, but over the decades. She has enough ideas, and enough measured fire, to last a long lifetime…”

As a visionary artist, Whitfield’s imagination astonished us — from her emotionally tender works, such as “New Baby” (1989) depicting her joy of swinging her newborn, and “Maybelline, Quiet Time” (2011), in which a mamma in a red polka-dot dress holds twin babies in a field of yellow sunflowers, to her arresting, complex lynching, “Narrative: Why Albert?” (1999), showing vulnerability and anguish in the form of outstretched arms. In 2019, Brian Boucher wrote about Whitfield’s lynching paintings: “ …Their small scale draws you in so close that the violence is too much to contemplate, even as you cannot tear yourself away from their beauty, infused by unspeakable sadness.”

It took almost 30 years for Whitfield’s lynching paintings to be presented by then curator — now director — John Fields, in a retrospective exhibition titled “Why?,” that took place in 2019 in the artist’s birth city of Birmingham, at the University of Alabama’s Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Art, and shared by Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Whitfield was included in the 1994 publication, Revelations: Alabama’s Visionary Folk Artists by Kathy Kemp, and was featured in Raw Vision 49. In 1996, she was artist-in-residence at American Folk Art Museum, New York City, and in 1997 she had a residency at The MacDowell Colony, Peterborough, N.H.; in 2000 she received a grant from New York’s Pollock-Krasner Foundation.

Whitfield continued to paint prolifically until ill health stopped her in 2015. How prescient was Margaret Moorman’s 1991 review? Indeed, in her decades-long lifetime, Whitfield created a legacy filled with enough ideas and enough measured fire for her enduring status to be remembered in art history.