Top lot in the sale was this Aymara man’s ceremonial llacota mantle from Bolivia, Seventeenth-Eighteenth Century, which surpassed its $3/5,000 estimate to sell for $16,250.

Review by W.A. Demers, Photos Courtesy Material Culture

PHILADELPHIA – There were 773 lots offered and 748 sold when Material Culture presented the single-owner Cathryn Cootner collection of ethnographic, tribal and textile arts on November 13-14.

Cathryn M. Cootner (1937-2021) was a fixture in the world of ethnographic art and textiles. Her remarkable passion for tribal arts of all kinds was known from New York’s Hajji Baba Club to San Francisco’s annual Tribal Arts Show. An eternal student, she collected and studied, taught and exhibited diverse tribal arts for more than 40 years.

She gave her first university lecture on textiles in 1968. By 1981, she was guest curator at the Textiles Museum in Washington, DC, and the next year she was appointed by San Francisco’s M.H. de Young Memorial Museum to be their first associate curator in charge of the rug collection. Later becoming curator of tribal rugs and curator-in-charge of the textiles department, Cootner’s robust acquisition and exhibition program is credited with transforming the museum into the well-respected repository for high-quality textiles and Oriental rugs that it is today. Chief among her accomplishments was a watershed exhibition of Caroline and H. McCoy-Jones’ unsurpassed collection of Anatolian kilims in 1991.

Born in Presque Isle, Maine, and graduating from Colby College in 1959, she moved to Boston, where she worked as a model, and a staffer for John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign. There, she met Paul H. Cootner, noted economist and MIT professor, and they married in 1964.

After moving to Palo Alto, where Paul taught economics at Stanford, Cathryn gave birth to a son, Joshua, in 1971. She was a 41-year-old housewife when Paul died suddenly in 1978, leaving her with a 6-year-old to raise on her own. She had no income, no formal training in any field, and no family for 3,000 miles. Working long hours, she built a career out of her passion for textiles, turning herself into an internationally renowned expert.

A large Ersari chuval from Turkmenistan, mid-Nineteenth Century, left the gallery at $8,750, far above the $500-$1,000 estimate.

Also an appraiser and author of two books, Cootner’s interests and passion for tribal arts were as much a part of her personal life as her professional. Outside the museum walls, she was a consummate collector, amassing a houseful of ethnographic textiles and objects from around the globe, each one with a story she loved to share.

After leaving the museum, she continued her career in the world of tribal art as an author, speaker, collector and dealer into her 80s.

Topping the sale were two antique male garments. An Aymara man’s ceremonial llacota mantle from Bolivia, Seventeenth-Eighteenth Century, surpassed its $3/5,000 estimate to sell for $16,250. Describing its rare and very fine condition, the catalog stated, “This purple center with gold stripe example is as good as it gets, since most of these garments were destroyed in the official purges of the late Eighteenth Century and their use did not resume in the republican period except as rare heirlooms. Its size was 56 by 43 inches.

Fetching $10,880, twice its high estimate, was a Bolivian Aymara Ccahua man’s ponchito, also Seventeenth-Eighteenth Century. A true Ccahua ponchito that was opened in the late Eighteenth Century in accord with official edicts, the 54½-by-36-inch tunic featured a purple center with red selvedges and lloque striping, a prize heirloom of finely woven alpaca.

A large Ersari chuval from Turkmenistan, mid-Nineteenth Century, left the gallery at $8,750, far above the $500-$1,000 estimate for the 5-foot-1-inch-by-1-foot-10-inch wool textile.

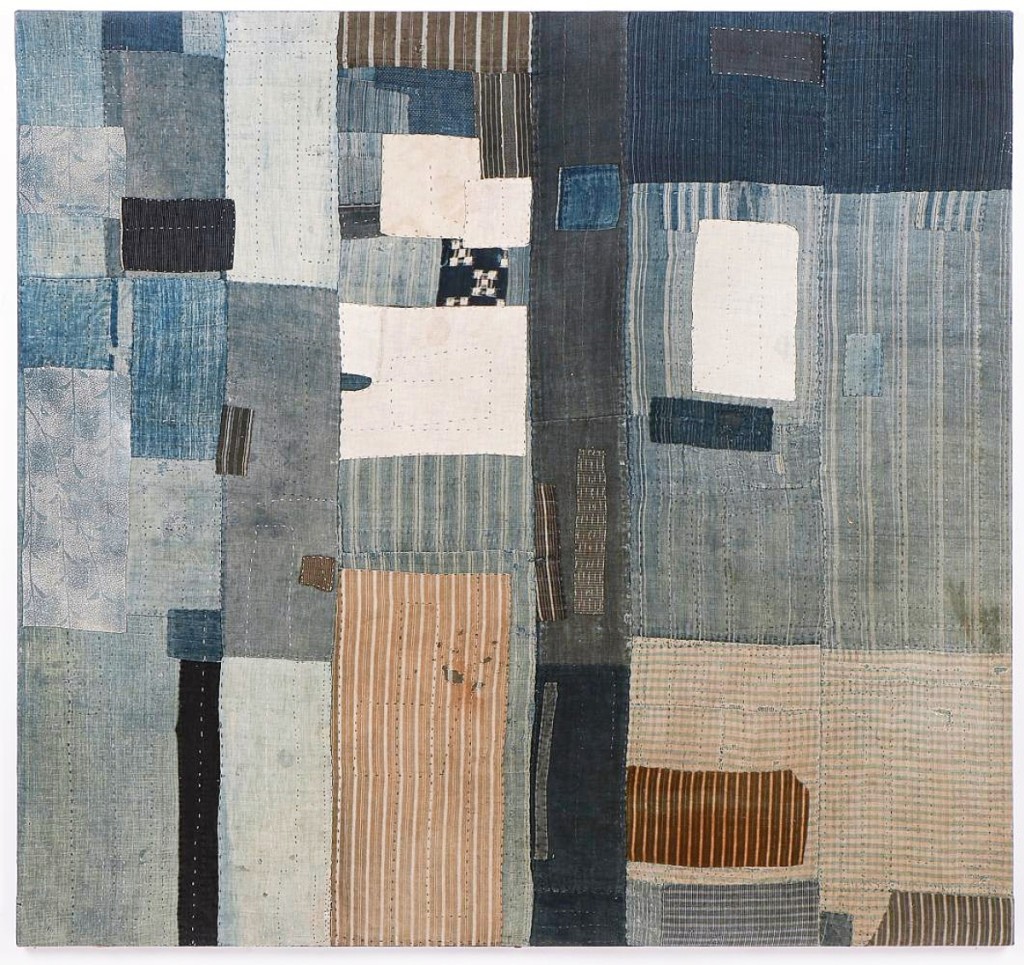

From Nineteenth Century Japan came a patchwork/boro cloth, 57 by 60 inches, that resembled a Modern abstract painting with a random arrangement of recycled cotton fragments and finished at $6,050.

The sale also featured some contemporary sculpture. A penwork sculptural vessel of enameled copper alloy and wire with cylindrical base by June Schwarcz (American, 1918-2015) was bid to $8,125. The Renwick hosted a 60-year career retrospective for the innovative California enameler in 2017. The technique she used was ancient – the high-temperature fusing of glass and metal that dates back to the Thirteenth Century BCE, but she combined it with electroplating, an industrial process that allowed her to create singular, varied, largely abstract work over a 60-year period that was always marked with innovation.

At $7,680, nearly twice its high estimate, a Seventeenth Century Ottoman silk velvet & metal thread woven catma had provenance to Christopher Gibbs, Ltd., London. It measured 53 by 26½ inches.

From Nineteenth Century Japan came a patchwork/boro cloth, 57 by 60 inches, that resembled a Modern abstract painting with a random arrangement of recycled cotton fragments and finished at $6,050.

A large Nineteenth Century silk ikat textile composed of central ikat weaving with blue ground framed by colorful red, green, yellow and blue and lined with Russian cotton came from central Asia and found a buyer at $5,935. It measured 81 by 64 inches.

Beyond choice textiles, an African Dogon shrine triple ladder from Mali nearly doubled its high estimate, earning $4,375. Carved wood and on a stand, it had provenance to James Willis Tribal Art, San Francisco, and stood 31 inches high on its stand.

A rare antique Shan engraved skull, Kapala, Nineteenth Century, realized $3,840. On it was Burmese writing, tantric square and magical symbols. It had been cut from the frontal or parietal portion of the skull and used in Shamanistic Bonpo ritual in Burma. It was presented on a stand and stood 5¾ inches high.

Enormous palms turned to face outward, with hands raised in the classic style of the region, three ancient Dagestan bronze idols from the Kaitag region took $3,000.

Bringing the same amount was a Brazilian Kayapo Indian ceremonial headdress from the Xingu River area. Created in the mid-Twentieth Century of plant fiber, reeds and feathers, it had provenance to Michael D. Higgins, American Indian Art, Tucson, Ariz., and measured 30 by 21 inches.

An antique African Kirdi Cache Sexe beaded apron from Cameroon was lively with beads, plant fiber and cowrie shells. The 9-by-24-inch textile had a small estimate of $200/400, but did much better, commanding $3,050.

Taking $3,000, twice high estimate, were three ancient Dagestan bronze idols from the Kaitag region; their hands were raised in the classic style of the region, enormous palms turned to face outward. Russian archaeologists have found some examples of these small idols buried with remains of clothing on them – perhaps the reason why their bodies are relatively undecorated.

Another rare headdress crossed the block, this one an early Twentieth Century example from the Solomon Islands. It sold for $2,940, neatly triple high expectations, and featured Kobu palm leaf, bamboo, beads, plant fiber and pigment.

Additional highlights in the sale included a neolithic carved stone idol, possibly Anatolian, and a Kenyah/Kayan Dayak warrior’s shield from Borneo, each $2,800; and an African Tabwa diviner’s headdress (Nkaka), Democratic Republic of Congo, mid-Twentieth Century, selling for $2,680.

Prices given include the buyer’s premium as stated by the auction house. For information, www.materialculture.com or 215-849-8030.