By Laura Beach

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Anyone who watched Super Bowl LIV in February with half an eye toward the much-hyped television spots that punctuated it will likely remember the shoot-out, or rather dance-off, at the Cool Ranch. To the beat of “Old Town Road,” the duel pitted country rapper and hip-hop artist Lil Nas X against actor Sam Elliott, the tall drink of water who has for more than 50 years personified the American West in film.

Long before Sam Elliott, the West was embodied by another lanky artist, one whose attenuated silhouette and bohemian habits today call to mind James A.M. Whistler but whose boots, hat and ubiquitous thunderbird watch fob in his own time signaled his fierce regionalism. He was Maynard Dixon (1875-1946), a California-born aesthete whose intrepid journeys through much of the West elevated his status as a foremost interpreter of his time and place.

No longer as well known as his second wife, photographer and social documentarian Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), the subject of a new retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art through May 9, Dixon gets his due in the comprehensive volume Maynard Dixon’s American West: Along The Distant Mesa by gallery owner and Dixon enthusiast Dr Mark Sublette and a companion exhibition of the same name organized by Sublette with assistant museum director Dr Tricia Loscher at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West (SMoW) through August 2.

If Lil Nas X and Elliott are the latest symbols of a region that all but defines the American psyche, Dixon was one of the first. As conveyed in the 1986 PBS documentary series The West of the Imagination, artists shaped our understanding of the terrain beyond the Mississippi. “The visual image-makers have contributed as much as the writers to the fundamental myth of the American experience – the story of peopling a vast new continent by emigrants from the old European world who were forever moving West,” father and son historians William H. and William N. Goetzmann, creators of the series, wrote.

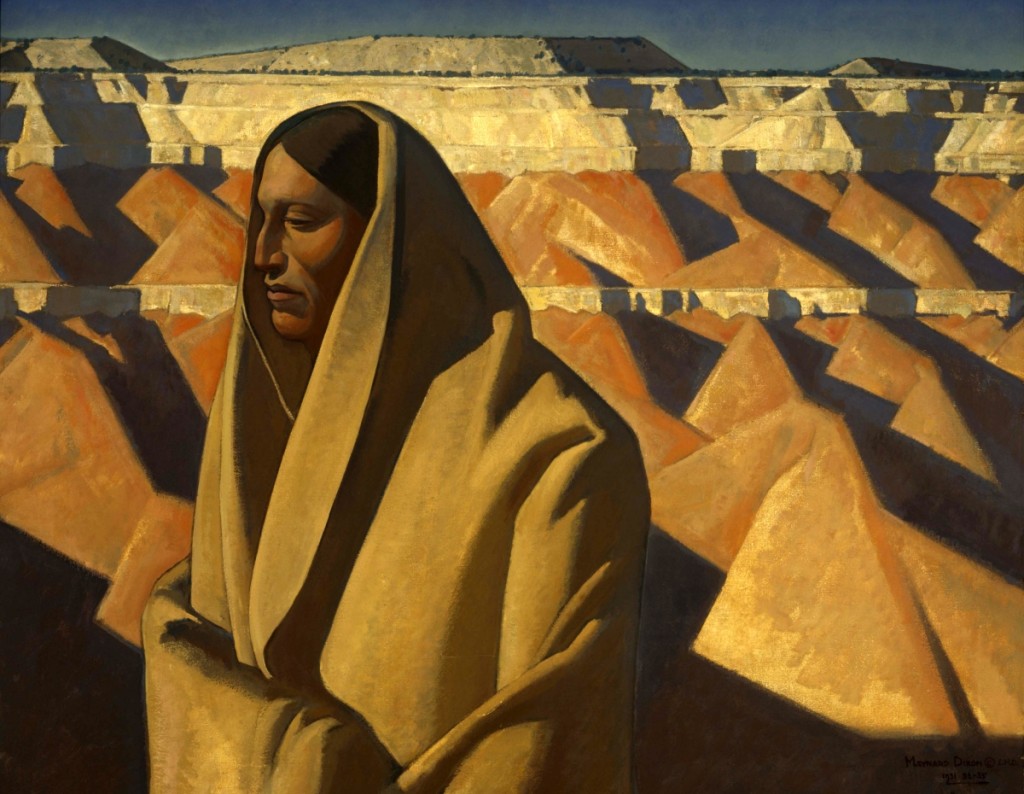

Dixon’s authenticity set him apart. From his first visit to Arizona and New Mexico in 1900 to his last summer in Utah in 1944, Dixon, who over the course of his career embarked on 22 working trips from Montana to Mexico, determinedly recorded the sere landscape and its ancient communities as he saw them. As Sublette writes, “Dixon thus took one of the most creative professional detours in Western art, devoting himself to reexamining the sky, land and people of the Southwest with a remarkably fresh vision. He became a master of portraying the archaic . . . Instead of copying the wild rider popularized by Remington, or even Russell’s comic cowpoke, Dixon fought against stereotypes.”

Always remarkably clear-eyed about his own ambitions, the 16-year-old Dixon wrote to Frederic Remington in 1891, enclosing a sketchbook that included his first portrait from life. The master’s encouragement prompted the youth to seek training at San Francisco’s California School of Design, where he remained for only three months. He began his career as an illustrator, winning his first commission in 1893 from Overland Monthly; art directing the Sunday magazine of William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner; and contributing to the influential Sunset magazine through 1934.

Editor and preservationist Charles Lummis, who became a father figure to Dixon after they met in 1895, advised the young artist to “travel east to see the real West” but warned, “Don’t be used. Go hungry first. Don’t let any of them buy you. Don’t sell anything that isn’t in you. Don’t forget your backbone.” Working in New York City for the top magazines, Dixon met Charles M. Russell in 1908 and became friendly with Ernest Blumenschein, Buck Dunton, Robert Henri and other talents of the day.

His paintings selected by New York’s National Academy of Design for exhibition, Dixon returned to California in 1912, intent on pursuing his fine-arts career. He opened a studio in San Francisco, where he remained until 1939, when he and his third wife, artist Edith Hamlin, made plans to divide their time between a winter home in Tucson, Ariz., and a summer retreat in Mount Carmel, Utah. Even as he resisted definition by others, Dixon, over the arc of his nearly six-decade-long career, stayed abreast of the major artistic trends of the day, from reductive abstractionism to Social Realism. “Everything Dixon experienced in some way, shape or form influenced his work,” Loscher says.

A former physician who founded Medicine Man Gallery in 1992 and maintains a private museum dedicated to Dixon, Sublette developed a passion for the artist soon after he settled in Tucson in 1990. “I did a Dixon retrospective in 1996 and knew from that point that I would always handle his work, that the pieces coming through my hands were historically important. When Western Spirit contacted me, it was the impetus to finish the book, which I worked on for the last three years,” Sublette says.

The dealer benefitted in his research from relationships with the Dixon and Ronstadt families. Maynard Dixon built his Tucson house on land given to him by Gilbert Ronstadt, father of singer Linda Ronstadt and a Tucson native. “The unsung heroes of this project are all the people who have walked into my gallery over the last 25 years, elderly people who knew Dixon and dealt with him in some form or fashion. They were kind enough to sit and talk to me. Their recollections really added to my understanding of who the artist was,” Sublette says.

Encompassing more than 250 paintings, drawings, photographs, furniture and related memorabilia borrowed from Brigham Young University, the largest public repository of the artist’s work; the Oakland Museum of California; the Smithsonian American Art Museum; the Denver Art Museum; the Phoenix Art Museum and other public and private sources, “Maynard Dixon’s American West” unfolds in the Great Hall at Western Spirit.

“We wanted to impress upon visitors Dixon’s range and importance as an artist, not only in the West but nationally. Through his many drawings, you can see his different trips and the time he spent on the Navajo and Hopi reservations, where he produced intimate sketches of Native American people,” says Loscher, who also included work by Lange and Hamlin.

Favorite works include the 1925 oil painting “Cloud World.” Loscher says, “It’s a magnificent piece, brilliant and dramatic. If you’ve spent time in the Southwest, you’ll recognize those stacks of clouds in a vast expanse.”

Four robed and faceless figures huddle together in the Depression-era “Shapes of Fear,” which won major prizes in exhibitions on both American coasts in 1931 and 1932. Dixon’s agonized commentary speaks of a malaise both personal and public.

Dixon is rarely credited for what may have been his most visible contribution: the orange vermilion color of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. Not only did the artist lobby for the project with drawings published in the San Francisco Chronicle, in 1935 he wrote bridge designer Irving Morrow, whom he had recommended for the job, urging, “if our bridges – particularly the Golden Gate Bridge – are to appear the wonders of the world they are supposed to be, they should most certainly be painted an eye-filling color.” Dixon’s letter to Morrow, plus ten preliminary drawings of the bridge by Dixon, surfaced in Morrow’s papers and are now part of the Maynard Dixon Museum.

Both book and exhibition conclude with a sampling of artists who are Dixon’s spiritual successors. “Maybe more than anything, Dixon would have cared that his voice and vision inspired successive generations in their interpretation of the West. He believed it was fine to have teachers but thought an artist needed to take inspiration and make it his own. Artists who have followed him have a singular vision,” says Sublette, citing Ed Mell (b 1942), Josh Elliott (b 1973), Jill Carver (b 1968) and Matt Smith (b 1960) as examples.

“Kit Carson with Mountain Men,” 1935. Oil on canvas. Peterson Family Collection. —Loren Anderson photo

Though he does not paint and doubts he ever will, Sublette names himself a disciple of Maynard Dixon, including in the book a photograph he took on a research trip to the Navajo Nation, a tract spanning portions of Arizona, Utah and New Mexico. He called the image “Distant Mesa,” only to discover a 1922 painting by Dixon of the same title and similar, perhaps even the same, topography. “Obviously, I purchased the piece,” Sublette writes, adding, “Maynard Dixon had invaded my soul in some magical way I still didn’t comprehend.”

In conjunction with the show, Western Spirit is airing a feature-length documentary on Dixon on March 21 and April 25. Narrated by actress Diane Keaton, it considers the artist through his paintings and drawings, family photographs by Lange, and interviews with his descendants, friends and scholars. Farther south, at the Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery, an exhibition of new paintings by Josh Elliott is on view March 20 through April 10, supplanting a presentation of work by Ed Mell, which closes March 13.

Ever creative, Sublette continues apace with his podcast Art Dealer Diaries. Eighty-six interviews with artists, curators, writers and publishers are available on YouTube, Apple and Google (https://artdealerdiaries.com.) Sublette is also taking orders for The Candyman, the eighth book in his Charles Bloom murder mystery series, which tracks the adventures of a Santa Fe dealer in Western and Native American art. The most recent Bloom book, Guardian of the Cornfields (2019), revolves around a Dixon painting with a sordid past and the 1934 disappearance of artist-explorer Everett Ruess, a Dixon companion, in the Utah desert. The books are available in print and audio form from Medicine Man Gallery, Amazon and Audible.

With more than 650 illustrations, Maynard Dixon’s American West: Along The Distant Mesa is for sale on Amazon or from Medicine Man Gallery, 6872 East Sunrise Drive, Suite 130, Tucson AZ 85750. For more information, 520-722-7798 or www.medicinemangallery.com.

Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West is at 3830 North Marshall Way in Scottsdale. For more information, 480-686-9539 or www.scottsdalemuseumwest.org.

Photos courtesy Western Spirit and Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery. All works by Maynard Dixon unless otherwise noted.

_-_copy.jpg)