“She Wore Her Family’s Quilt” by Sedrick Huckaby, 2015. Oil on canvas. Photograph by Gregory Staley.

By Kristin Nord

MUNCIE, IND. – “Memories and Inspiration: The Kerry and C. Betty Davis Collection of African American Art” has been drawing enthusiastic audiences throughout the United States with its deeply personal exploration of the African American experience in the Twentieth Century. It stands as testament to the strength and resilience of Black community values as it bears witness to a century marked by strife and social change.

The exhibition, now running at the David Owsley Museum of Art though December 22, draws upon a collection acquired with modest means and a good bit of ingenuity by a lifelong Atlantan, Kerry Davis, and his wife, Betty, a local television producer. Its tour is being underwritten by International Arts and Artists of Washington, DC, and by Arts Alive Funding from the College of Fine Arts at Ball State University.

Davis said recently that it was undoubtedly a lifelong fascination with creativity that shaped his passion for collecting art. “The making something out of nothing, the making a way out of no way…making do, surviving,” he explained, simply.

But it was through observations, study and personal connections that the Davises built what is seen today as one of the finest collections of Twentieth Century African American art in the country.

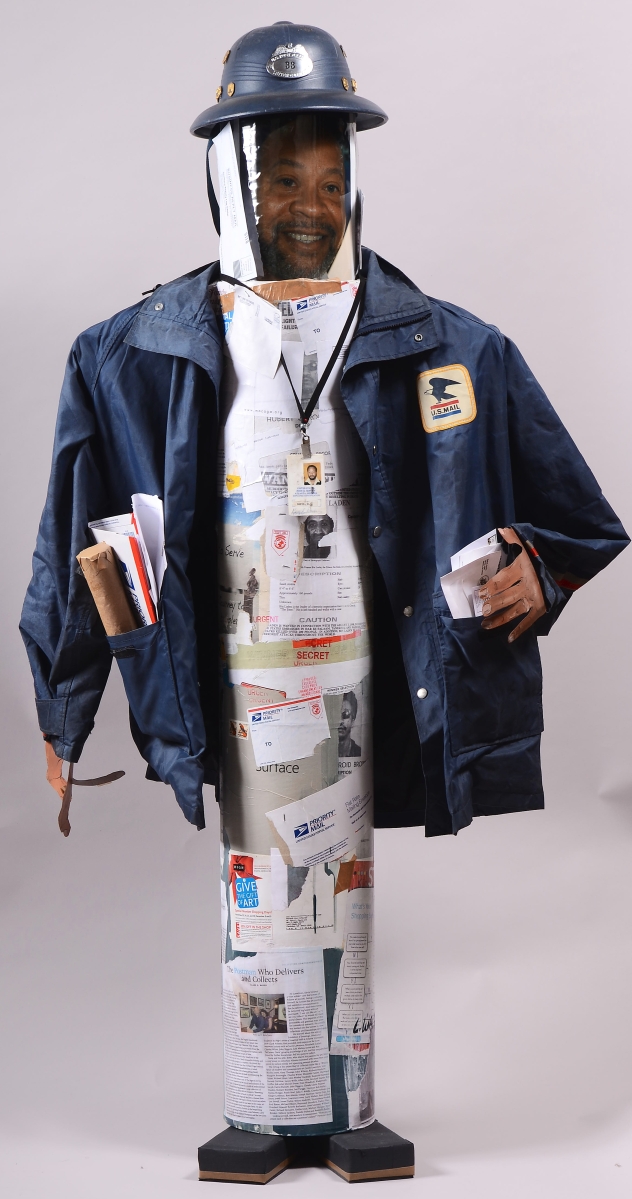

When Kerry bought his first work of art in the mid-1980s he was not thinking of a collection so much as something to hang on the walls of his apartment. After marrying Betty, the couple set out to acquire art with which to decorate their suburban home. Kerry was fresh out of the Air Force and had completed training as a carpenter. Lured by the prospect of a pension down the road, however, he took a job with the US Postal Service, and was soon delivering mail in the Peachtree Street arts district. Gradually, through independent study and research and conversation, Kerry began to build a serious collection.

Much as his father could repair anything, Davis’ carpentry skills enabled him to barter for art by offering framing services for nearly 17 years. He also stretched canvas, built shipping crates and helped transport and install exhibitions.

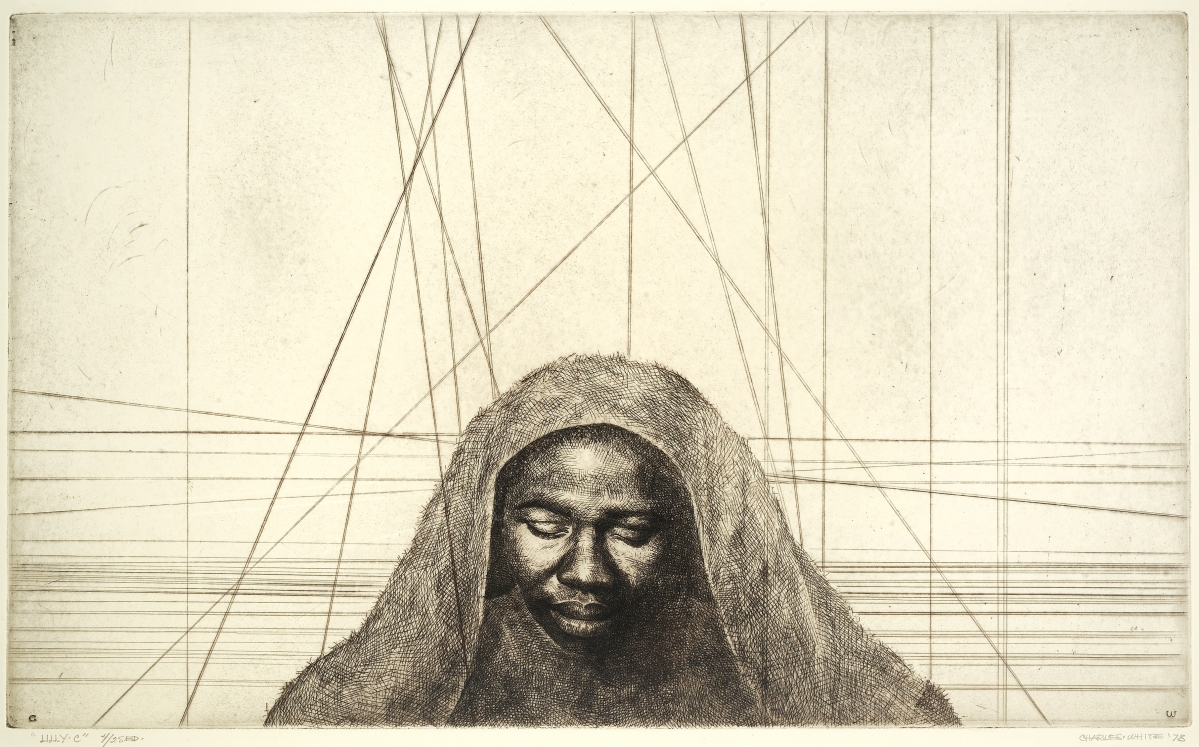

If visits to university galleries expanded his knowledge of art and art history, conversations with his customers, some of whom collected major art, as well as the artists themselves, opened the world to him in profound ways. He sought out off-the-beaten-track auctions and estate sales; and became adept at recognizing major works, like the pristine Charles White linocut, “My God is a Rock,” that he found wrapped in a print tube on a lucky day. He was resourceful in other ways, traveling to the hometowns of artists he was interested in on the chance that something might turn up. These excursions, in turn, led to many long-lasting friendships. Collecting became a major focus of the Davises’ married life.

“Shack with Chair” by Beverly Buchanan, 1989. Foam board. Photograph by Gregory Staley. ©2021 Jane Bridges.

Looking back on this, Davis said in some ways his collection was a marked departure from his childhood, when the framed images of Martin Luther King, John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Jesus at Gethsemane were the sole art mainstays in his and many southern African American homes.

“Growing up, I remember Atlanta being a friendly town, but at times filled with tension. Our parents sheltered us from much of any racial issues, or we were just too young to realize what was going on.

“I remember very well the riots after Dr King’s death, the many protests from the 60s, and the church rallies during the Civil Rights Movement. We had a strong sense of community. We had to care for each other.

“My work ethic, and a willingness to serve the community came from my father. He was also a deacon with a heart of a servant. His joy in serving others was infectious. He found favor with most people. He worked as a laborer at Atlantic Steel Co. and drove a cab evenings and weekends. He could repair anything, it seems. My father worked hard and was a great provider. I am committed to be just like him.”

To that end, Davis has served as a deacon for 25 years at Pleasant Place Ministries, a nondenominational church that grew out of a bible study group of mostly friends and family. His brother, who is coincidentally his identical twin, is the pastor.

Parenthetically, alongside the Davises’ efforts to support and honor Black art and personal history was their desire to share their collection. For many years their home has functioned as an informal museum, with some 300 works installed salon-style and enjoyed on a regular basis with fellow parishioners and neighbors.

As he educated himself, Kerry began to acquire works from artists from two historically renowned juried awards programs that had been established to bring visibility and recognition to African Artists during the early-to-mid Twentieth Century. One was the Harmon Foundation’s annual artists award program, initiated in 1926 by real estate mogul William E. Harmon, a native of the Midwest, at a time when Jim Crow segregation was pervasive in American society and African Americans were excluded from the general art world. The second was initiated by painter Hale Aspacio Woodruff, who established the art department at Spellman College in 1932, and who initiated the Atlanta University Annual Art Competition and Exhibition, which ran from 1940 to 1970.

As Davis trained his eye and broadened his collection, he acquired works by a number of these award recipients. But he also sought out young and emerging artists whose work spoke to him and whom he wished to support. The result was a deeply personal and highly eclectic collection that feels unified on fundamental levels.

From friendships with emerging artists, to its poignant chronicle of the African American diaspora overall, it would seem “Inspiration and Memories” is resonating for visitors on many levels.

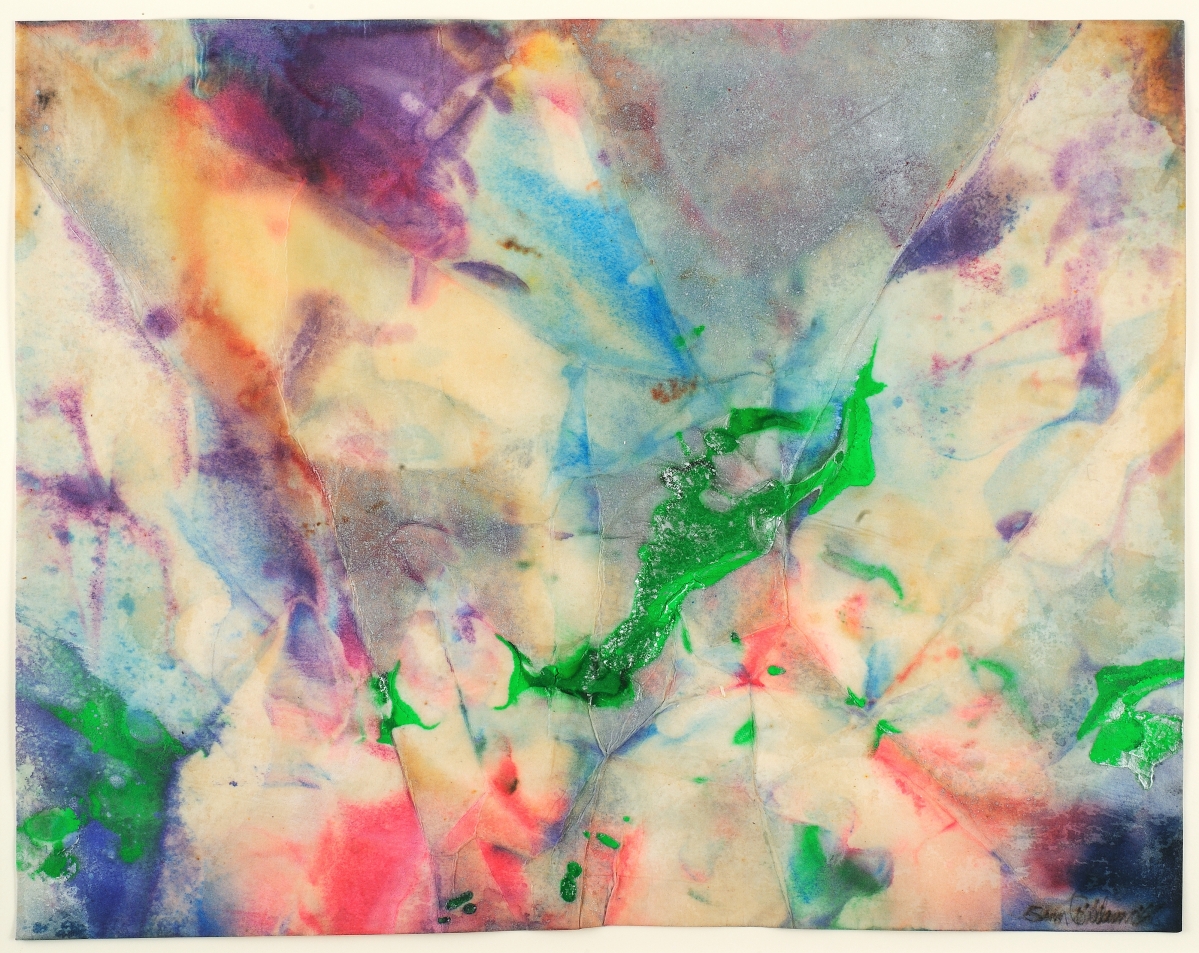

Moving through the DOMA galleries, we encounter a marquee lineup with works by Sam Gilliam, Romare Bearden, Loïs Mailou Jones, Alma Thomas, Ernest T. Crichlow and Moe Brooker.

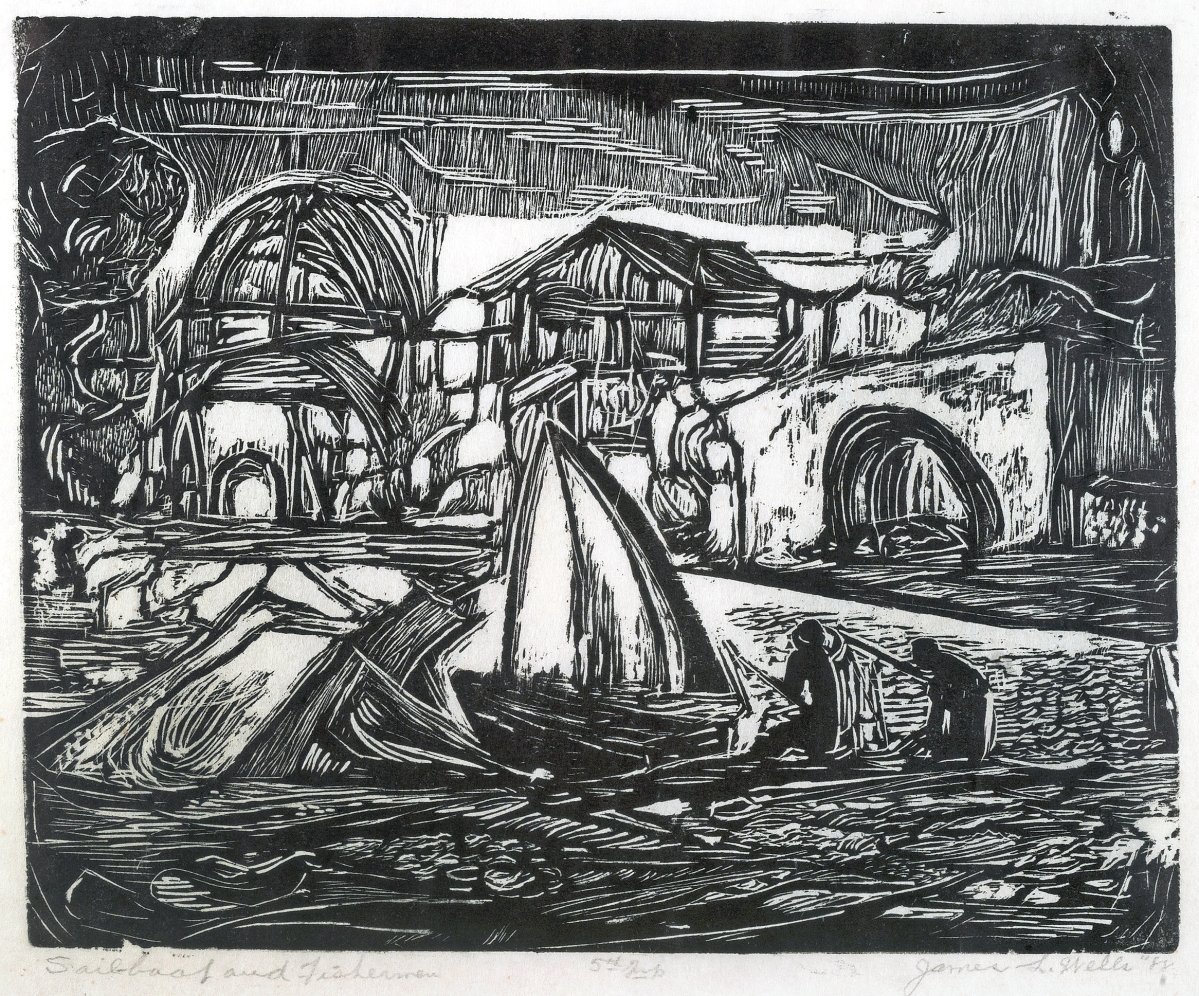

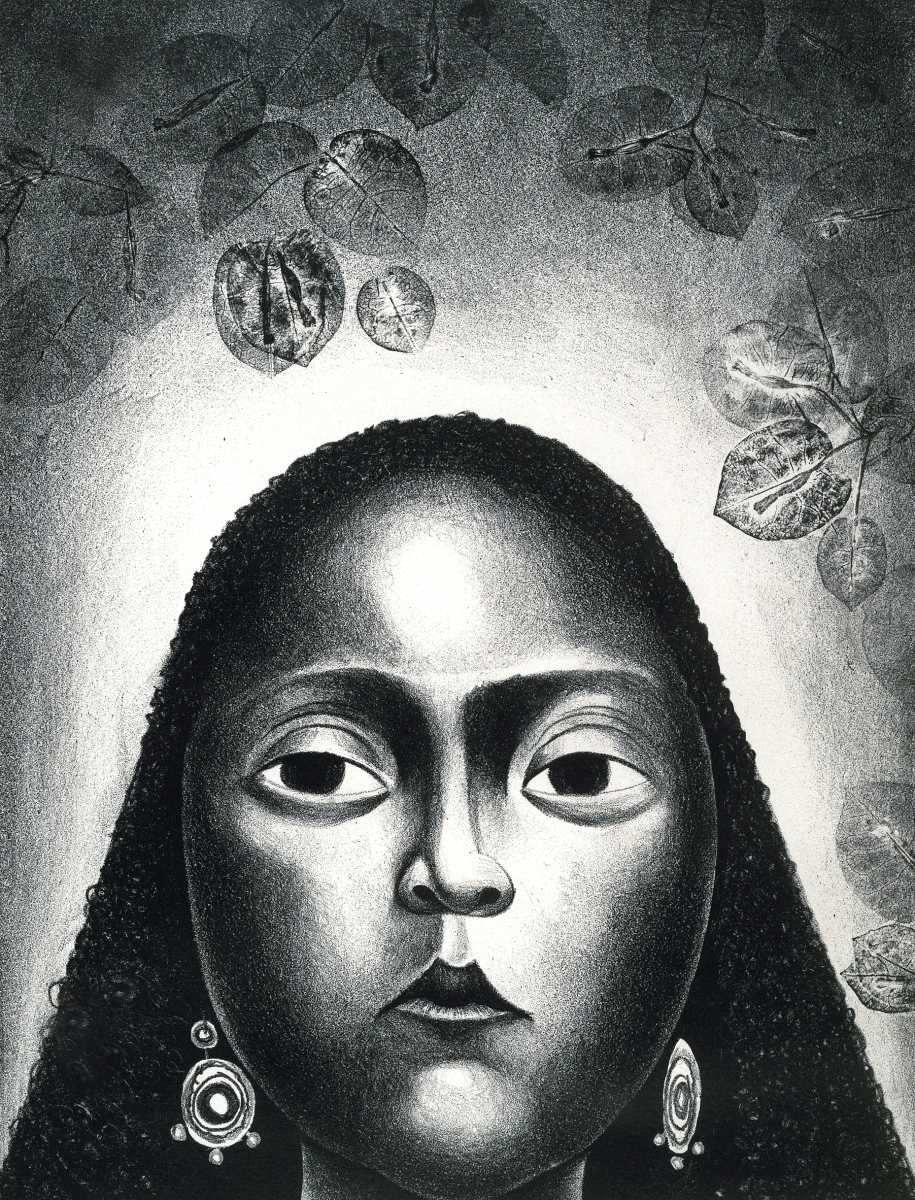

But there are also depictions of everyday life, from the woodcut “Mickey Dees,” 1987, by Michael Ellison, an artist who perfected a printmaking process he termed “subtractive block printing;” Ealy Horton Mays’ joyful painting, “Last Chocolate Ice Cream,” 2013; Elizabeth Catlett’s striking lithograph from 1979, “Prissy;” and William Ellisworth Artis’ “Michael,” a 2002 bronze cast from a 1962 mold.

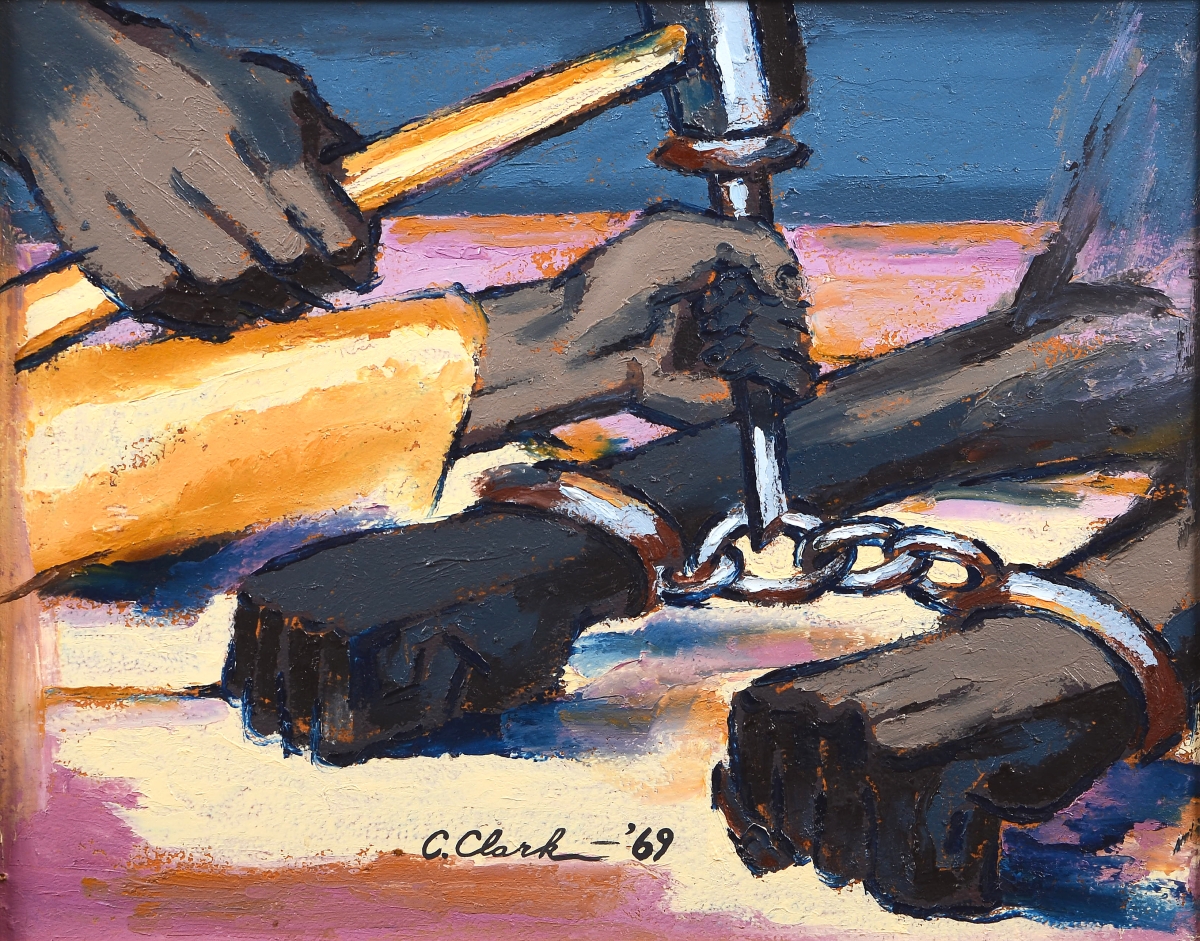

The Davises’ concern with social justice – and the collection’s images of struggle, courage, dignity and triumph over adversity – is seen in photography by Gordon Parks Sr (1912-2006), and in Claude Clark’s searing work, “Self-Determination,” 1969, in which one set of black arms is liberating another from shackles. There is Stefanie Jackson’s “Exodus,” 2004, a dramatic depiction of the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans; and Sedrick Ervin Huckaby’s “She Wore Her Family’s Quilt,” 2015, an oil painting that spoke to Kerry’s memories of church ladies receiving scraps of used clothing and transforming them. There is also Beverly Buchanan’s “One Room Shack,” 1997, reminiscent of the housing occupied by Kerry’s sharecropping forebears.

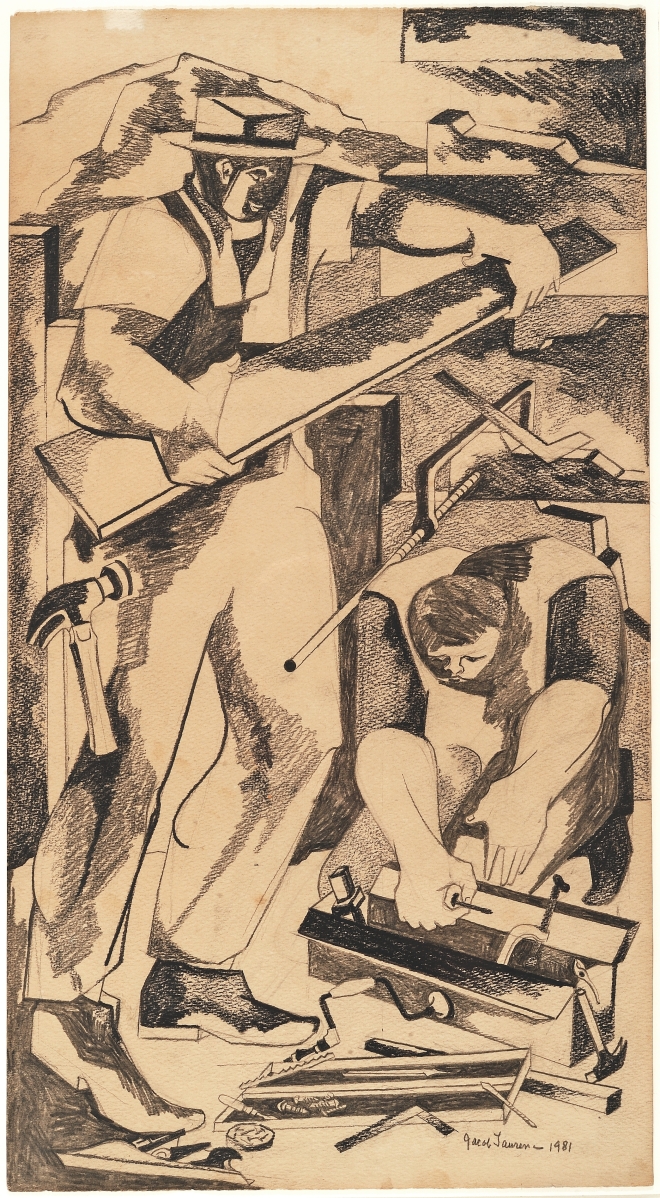

Overall, there are many works that seem to speak to the human spirit: a graphite drawing from Jacob Lawrence’s “Builder Series #8,” 1981, remains Kerry’s favorite piece in the collection, yet each work seems to come with a personal story.

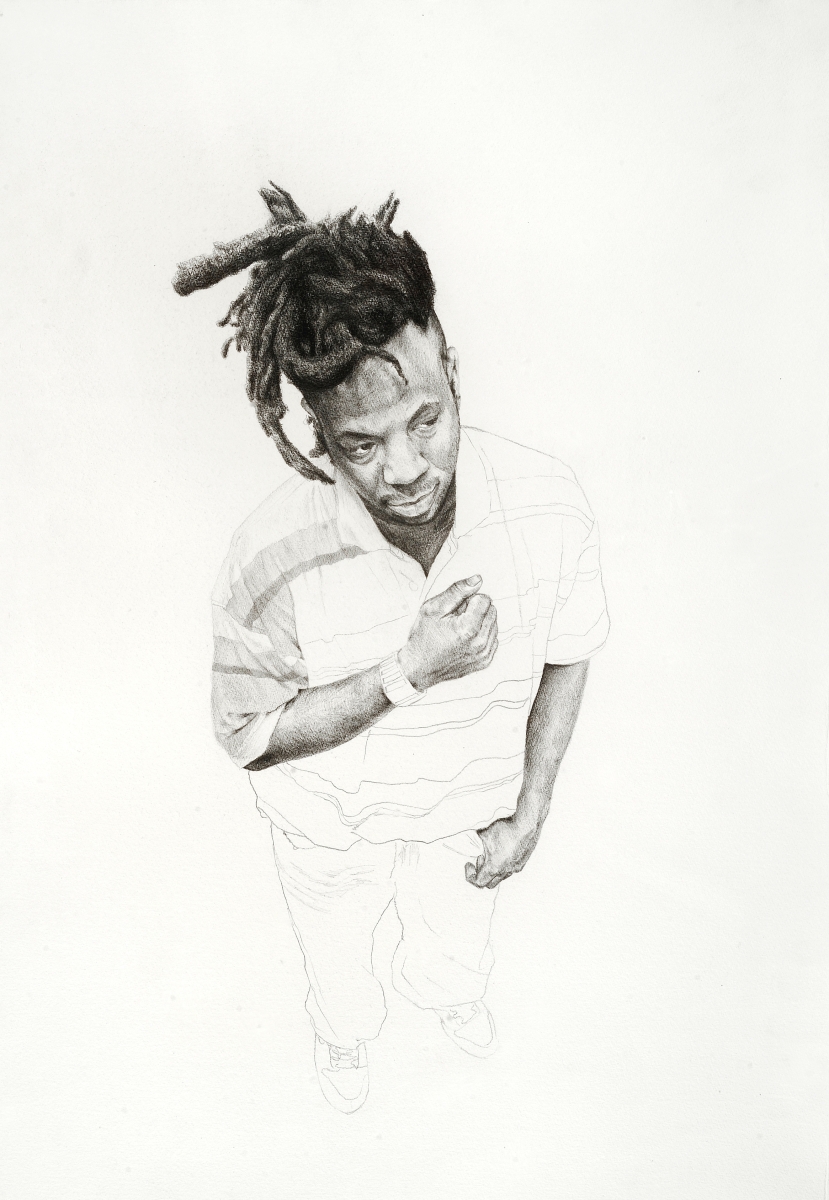

“Joanne by the Window” by William J. Anderson, 1986. Silver gelatin photograph. Photograph by Reis Birdwhistell.

Foremost Kerry credits Mildred Thompson, an artist-in-residence at Howard University, for teaching him “how to see art” and for encouraging him to collect art that spoke to him. When he once expressed his trepidation at approaching a particular artist, she quickly reprimanded him. “Baby, greatness is always approachable,” he remembers her saying.

Robert G. La France, director of the David Owsley Museum, said the DOMA has made its mission to be all-inclusive.

“It’s important for people to go into a museum and see people that look like themselves on the walls. These should not be bastions of just old dead white guys.”

Of particular interest to Indianans in this exhibition are works by Palmer Cole Hayden (1890-1973), a World War I army veteran, janitor and self-taught painter; and John Wesley Hardrick (1891-1968), a truck driver who studied painting at the Heron Art Institute in Indianapolis and became well-known for his murals, still lifes, landscapes and portraits.

To engage the Davis exhibition in further conversation, DOMA has curated a companion exhibition that pulls upon its own African American collection and will be introducing its regular 35,000 annual visitors to other significant African American works, including sculpture by renowned Chicago artist Richard Hunt.

Walking into the main gallery, Larry Walker’s totem-like sculpture of Davis is stationed, outfitted in his postal uniform, his friendly visage peering out from under his cap, draped with the trappings of his life and trade. One can’t help but smile, as apparently every visitor to the Davis home has done upon first encounter. It does seem as if this modest Atlantan-as-everyman has opened his front door and is welcoming his visitors in.

The David Owsley Museum of Art is on the campus of Ball State University, Fine Arts Building, at 2021 West Riverside Avenue. For information, www.bsu.edu.