“Beetle Wing Dress” for Lady Macbeth, Alice Laura Comyns‑Carr (British, 1850-1927), 1888, cotton, silk, lace, beetle‑wing cases, glass, metal. National Trust, UK (Smallhythe Place, Kent) ©National Trust Images/David Brunetti.

By Z.G. Burnett; Images Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

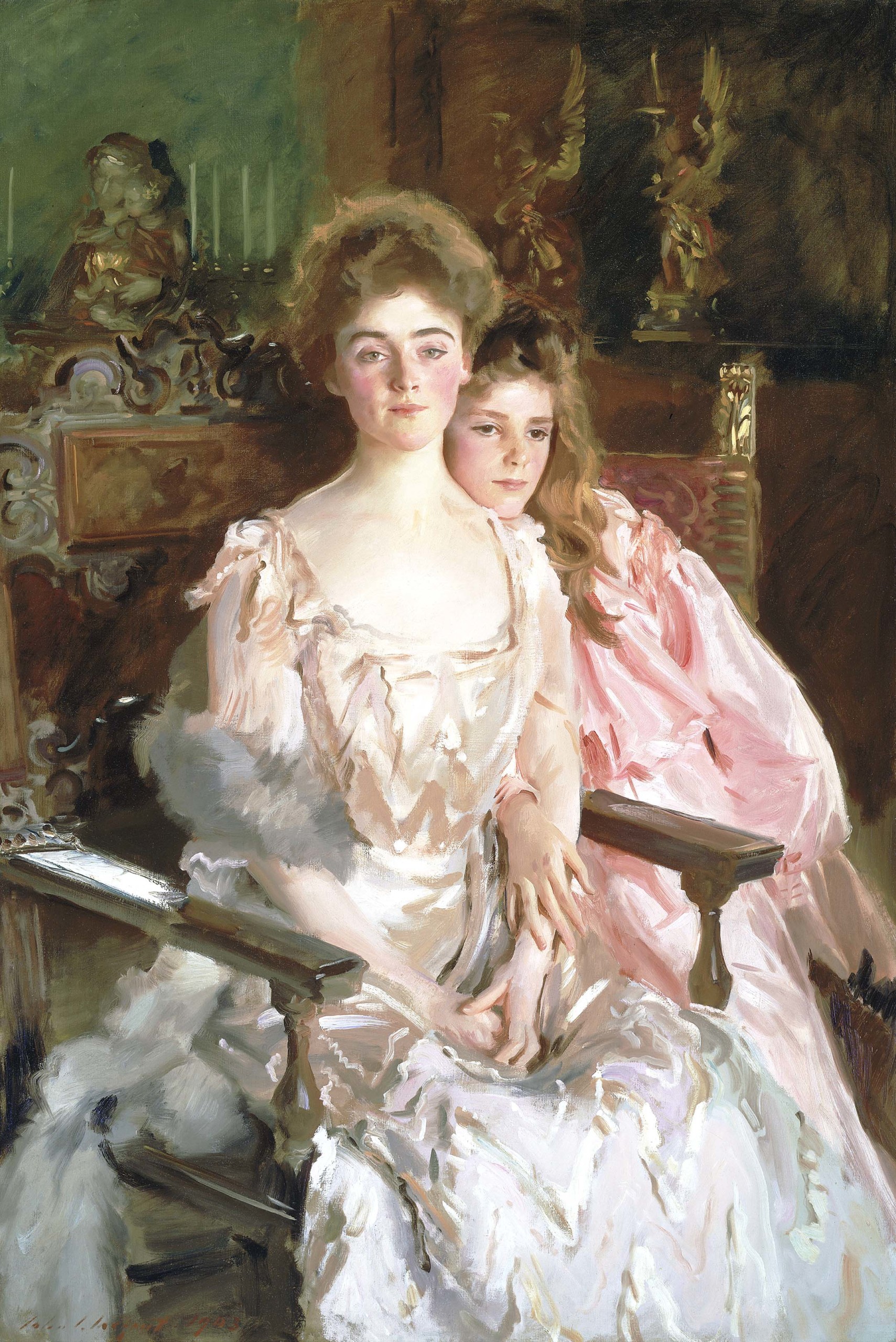

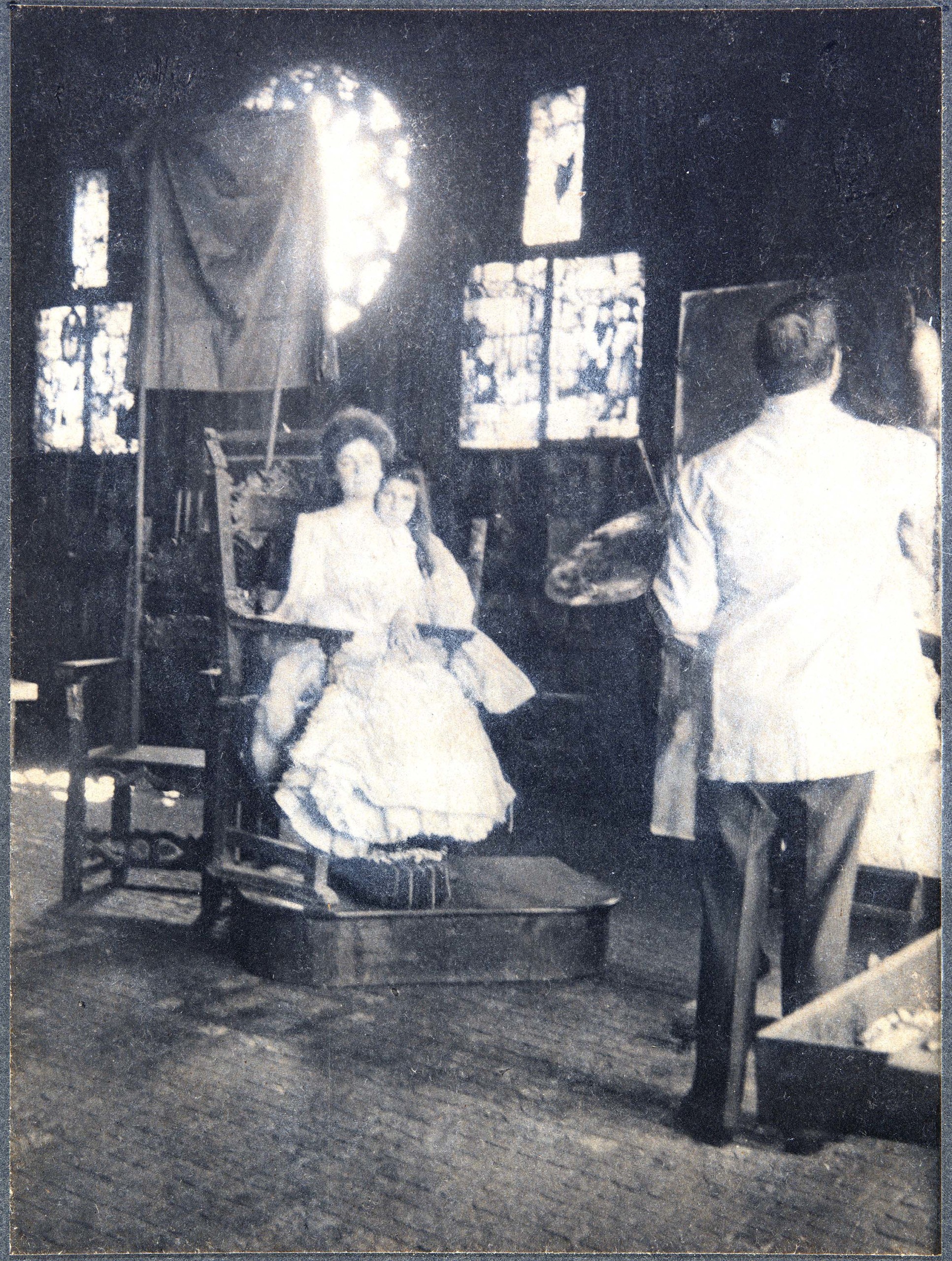

BOSTON — John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925) brought his sitters to life, but he did much more than simply record what appeared before him. He pinned and draped, he changed or ignored decorative details, and sometimes he simply made it up. Organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), and Tate Britain, “Fashioned by Sargent” explores the artist’s influence over his sitters’ images by illuminating the liberties he took with sartorial choices to express distinctive personalities, social positions, professions, gender identities and nationalities. The exhibition features approximately 50 paintings by Sargent — including major loans from museums and private collections around the world — along with more than a dozen dresses and accessories. Several of these garments are reunited for the first time with Sargent’s portraits of the sitters who once wore them. Through the lens of dress, “Fashioned by Sargent” presents exciting new scholarship and offers a new perspective on the artist’s creative practice. The exhibition will be on view through January 15.

“The MFA and Tate Britain both began supporting John Singer Sargent during his lifetime, and we’re proud to partner on this major exhibition that offers new perspectives on this beloved painter,” said Matthew Teitelbaum, Ann and Graham Gund director. “Sargent’s world, much like our own, was aware of the power of an image to mask reality and invent new narratives and identities. ‘Fashioned by Sargent’ encourages us to think deeply about the creation of a portrait — how it affects both how we see others and how the world sees us.”

“Through the dynamics of dress, we can see that Sargent did not pander to his wealthy clients — he was in charge, and art making always came first,” said Erica E. Hirshler, Croll senior curator of American paintings and exhibition organizer. “He clearly took the lead in creating his portraits, sometimes entirely ignoring his patron’s preferences to fulfill his own creative vision. Sargent controlled the sitter’s image.”

Hirshler conceived of this exhibition in 2017, following a paper she delivered at a 2016 symposium given in conjunction with the exhibition “Oscar Wilde: Insolence Incarnate,” which ran at the Petit Palais, Paris, from September 2016 to January 2017. The paper focused on male representation and interpretation in Sargent’s portraits, a topic also explored in “Fashioned By Sargent.” How Sargent dressed male subjects is intriguing, especially considering his gender and recent studies about his sexual orientation.

“Dr Pozzi at Home,” John Singer Sargent, 1881, oil on canvas. The Armand Hammer Collection, Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

“There are parallel interests [in this exhibition],” said Hirshler. “Reading a portrait as something different than what Sargent and his sitters expected in terms of how the public responded, and how he chose and/or manipulated what people were wearing for his own aesthetic agenda.”

Originally scheduled for 2021, “Fashioned by Sargent” was delayed due to the Covid-19 outbreak and successive lockdowns. This and other events that occurred throughout the pandemic created new considerations for how the exhibition was presented, both logistically and conceptually. “It was impossible to do the same type of exhibition that one would do before those events,” Hirshler commented. “Loans had to be renegotiated, some paintings changed hands… We also became more aware of the visual impression of what we wear, especially through Zoom [and social media].” Neither Sargent’s portraits nor online posts ever tell the truth, which has been emphasized more and more as the virtual pervades more of our reality.

The rising demonstrations for economic and social justice in the past few years also had an impact on the exhibition’s presentation. In June, unionized MFA workers ratified their first contact with the museum after 18 months of negotiations. Some of the major gains were raise in wages by July and the establishment of minimum pay rates. This is no mean feat, as rent prices in Boston rose 9.5 percent just since January of this year, with moves to enact rent control continually blocked in the state legislature. The cost of living in Boston is currently 50 percent higher than the national average, with Massachusetts overall ranking at 41 percent above, making it the fourth most expensive state in which to live.

“Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth,” John Singer Sargent, 1889, oil on canvas. Tate Britain, Presented by Sir Joseph Duveen (the elder) 1906. Photo: Tate.

The MFA’s unionization has become a focal point in this rise, and we asked Hirshler if an exhibition focused on the Gilded Age’s wealthy elite might face backlash. “That’s hard to anticipate,” she replied after some thought. “Boston wasn’t any fairer in Sargent’s time than in our time… One might wish more things had changed in the last 150 years, but the same disparities of wealth are evident today as they were then. Maybe that will help us understand the past a bit better [and] make people work for the future a little bit more.”

Another possible point of criticism might be the lack of people of color represented in the exhibition which, unfortunately in Sargent’s case, was a sign of the times. One of the scants images of a Black person in his oeuvre represented by studies of Thomas McKeller, an elevator operator-turned-muse whose image was the subject of “Boston Apollo,” an exhibition that ran virtually from February to October 2020 at the nearby Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. During this time, George Floyd was killed in police custody, sparking the Black Lives Matter movement.

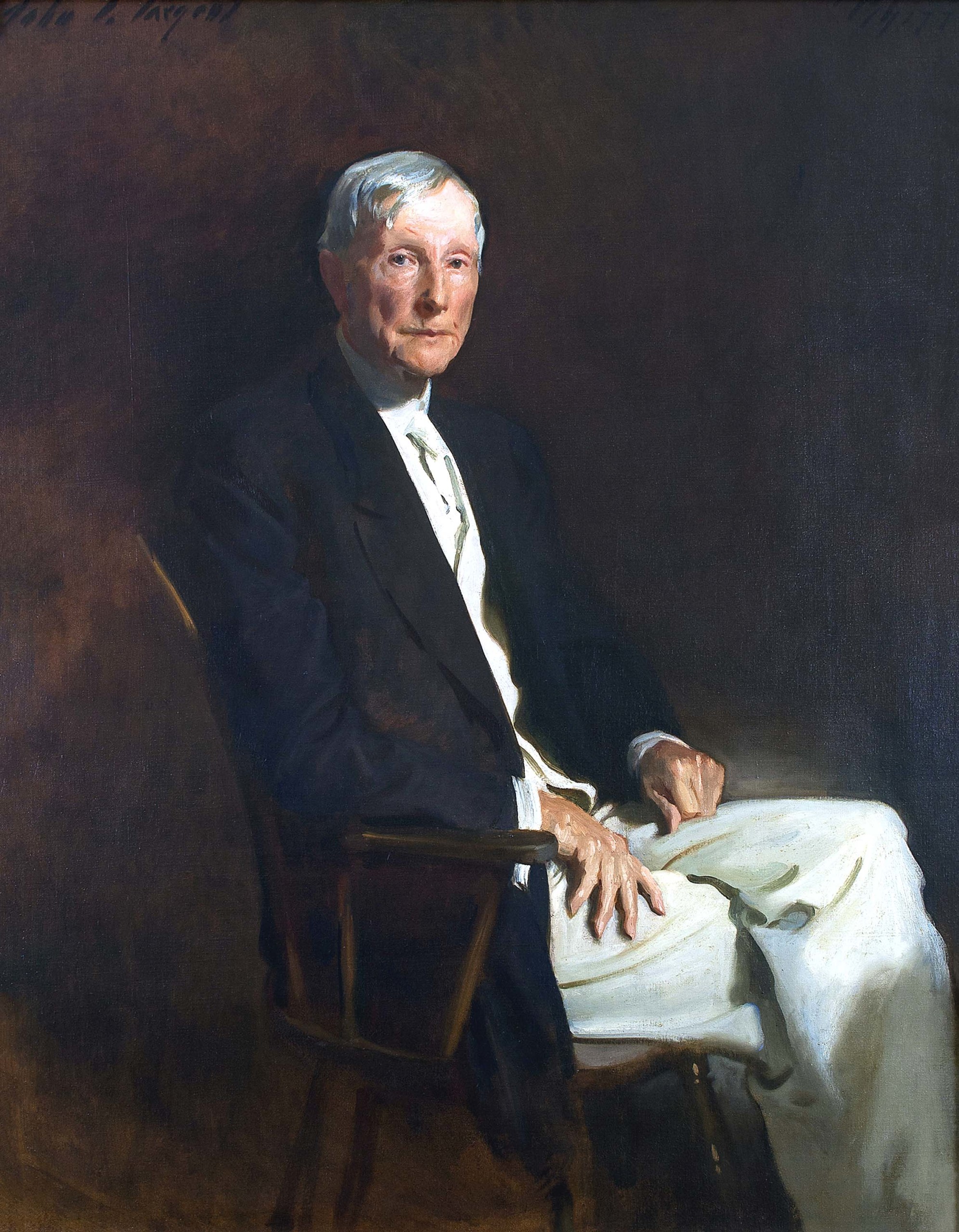

Addressing the racially homogenous catalog of “Fashioned by Sargent,” Hirshler said, “You can’t change the past, you can only improve upon it.” As an example, “Contemporary artists such as Kehinde Wiley are borrowing the same vocabulary from aristocratic portraiture as Sargent was, and Wiley has credited Sargent as a great influence [on his work].” Within the exhibition, Hirshler pointed out, it is also interesting to consider the portraits as a performance of wealth as the pool of those able to afford a portrait by Sargent steadily became more diverse with regards to its sitters’ social statuses, ancestries and religious affiliations. There was also the intention in this exhibition to not only show young, beautiful women, but to include older people, men and those who did not belong to the upper echelons.

“W. Graham Robertson,” John Singer Sargent, 1894, oil on canvas. Tate Britain, Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1940. Photo: Tate.

Another question of detractors may be whether or not Sargent’s portraits are relevant in contemporary times. Hirshler wrote in the exhibition catalog’s introduction, “Society portraits do not always endure.” However, what does endure is society’s ever-present need to lose itself in beautiful things. “Think of the Met Gala, people are fascinated with what some are able to do, wear and afford,” Hirshler said. “It’s a sort of voyeurism that doesn’t actually change.” As objects, the paintings have their own sensuality swathed in luxurious layers of paint. Many are also close to life size, making them impactful in a way that cannot be experienced through a screen.

“Every portrait is a performance, the sitters are aware that they’re being looked at,” Hirshler concluded. “We still do this in photographs today. In a way, we are all ‘performances.’”

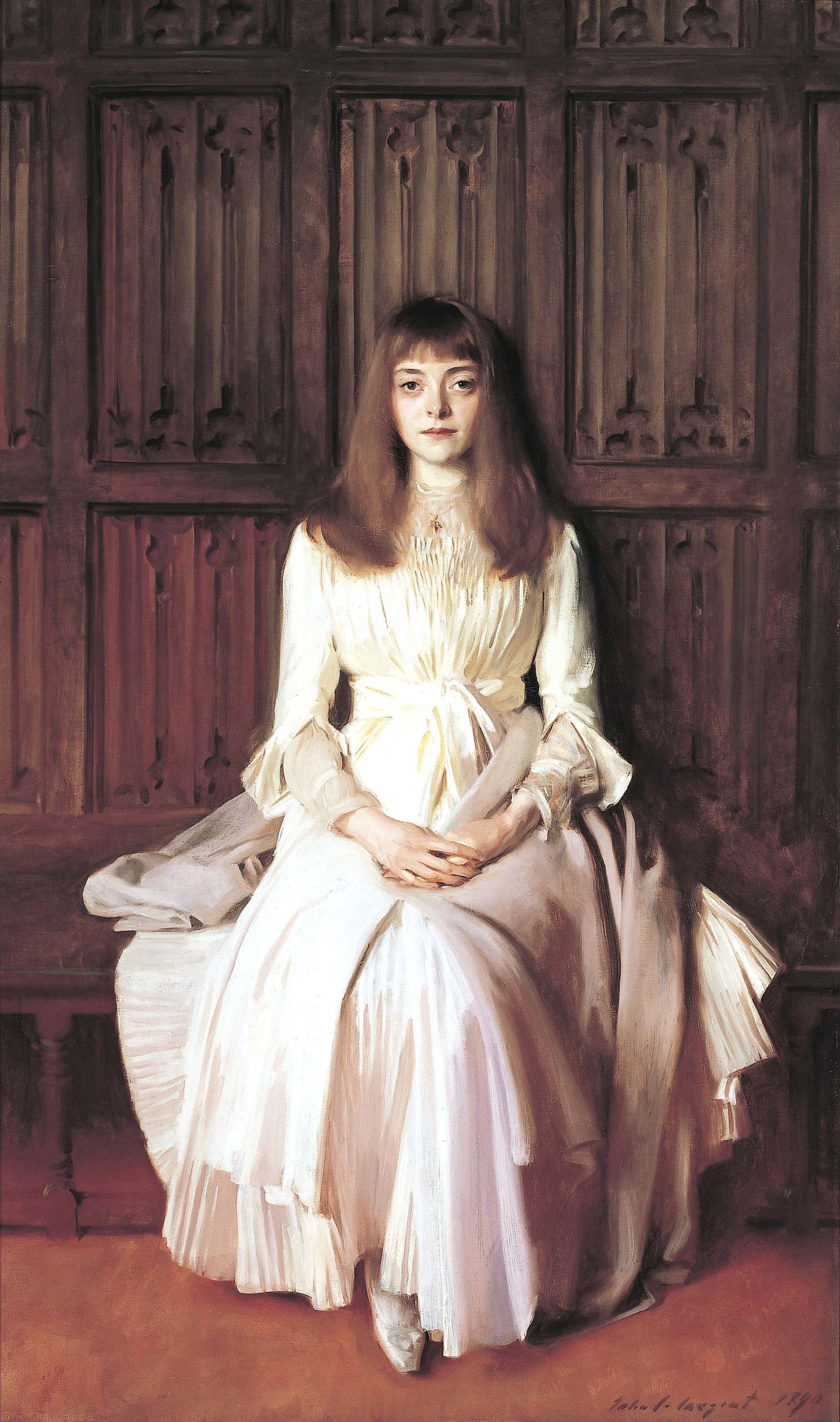

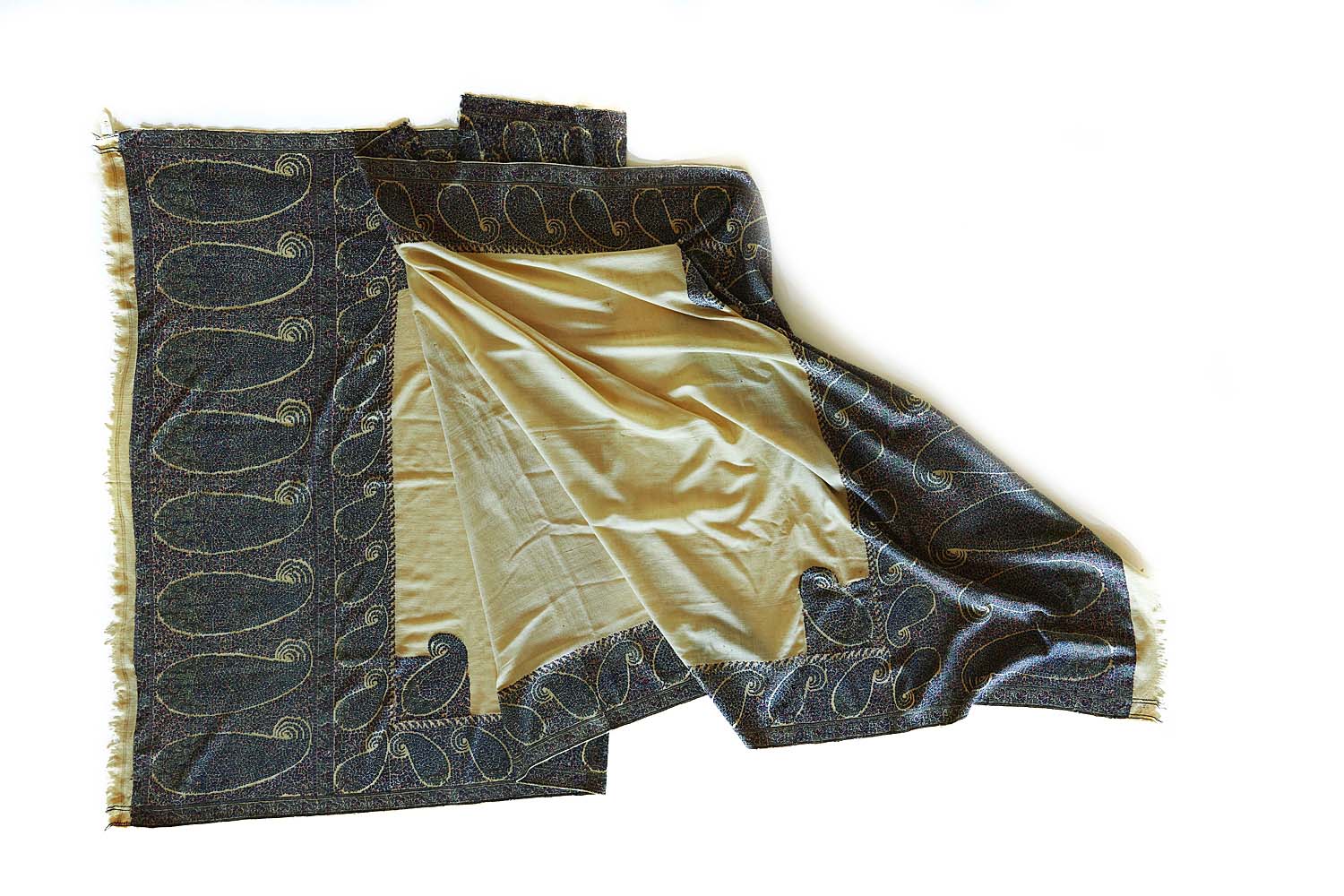

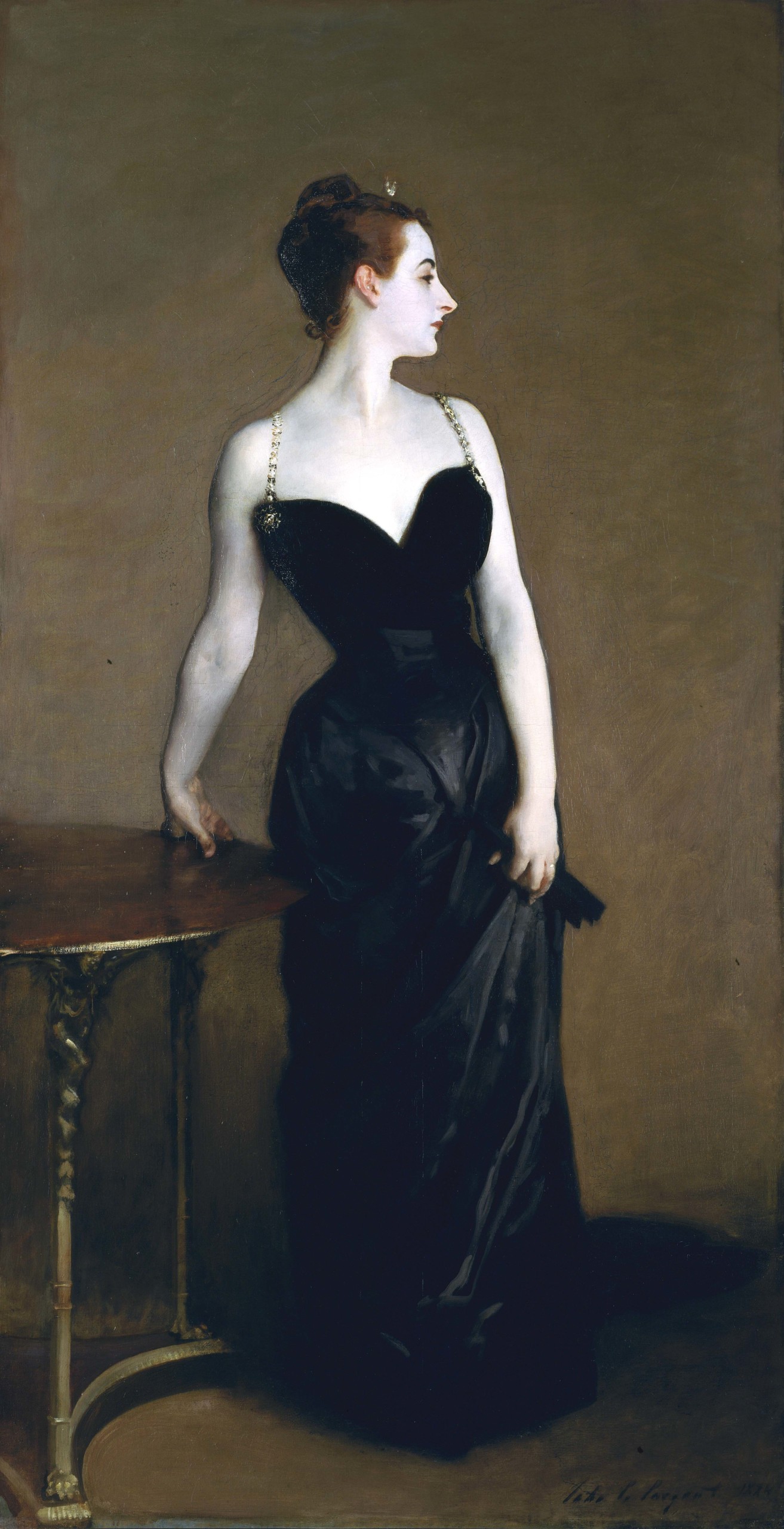

The exhibition is organized thematically, providing a dramatic glimpse into the world of the painter, the studio, his sitters and his technique: “The Studio in Black and White” reveals Sargent’s studios as sites of imagination. It explores his preference for painting sitters wearing black or white, inspired by Seventeenth Century painters Frans Hals and Diego Velázquez, and demonstrating his mastery of difficult techniques. “The Art of Dress” explores the role of fashion for women in society, and the way Sargent engineered his sitters’ choices to best serve his art. “Sporting with Gender” shows how Sargent used sartorial choices to signal gender ambiguity, tradition and the shifting roles accorded to men and women of the period. “Portraiture and Performance” includes subjects in dramatic costumes, among them Sargent’s portrayal of “Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth” (1889, Tate Britain), which is displayed for the first time with the brilliant green beetle-wing encrusted gown that she wore on stage. “Fashioning Power” emphasizes how clothing — whether uniform, ceremonial attire or even a deliberate choice of casual dress — can signify wealth and position. “Luxury in Cloth and Paint” closes the exhibition with a demonstration of Sargent’s fascination with the ways textiles could be manipulated — folded, twisted and draped — to explore light and shadow.

“Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau),” John Singer Sargent,1883-84, oil on canvas. Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916. Image ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In addition to style icons like “Madame X” (1883-84, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) and “Lady Agnew of Lochnaw” (1892, National Galleries of Scotland), major loans include “Lady Sassoon” (1907, Private Collection) and her black taffeta opera cloak (Private Collection); “Lady Helen Vincent, Viscountess D’Abernon” (1904, Birmingham Museum of Art), which was treated in the MFA’s Conservation Center for display in the exhibition; “La Carmencita” (about 1890, Musée d’Orsay), shown for the first time alongside the dancer’s sparkling yellow satin costume; the striking portrait of “Elsie Palmer” (1889-90, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center); and “Dr Pozzi at Home” (1881, Hammer Museum), which shows the accomplished surgeon in a flowing red dressing gown and Turkish slippers.

Fashion items, including Worth gowns and fans and six paintings by Sargent are drawn from the MFA’s own collection, which numbers almost 600 works by the artist in all media — the most comprehensive assemblage of his art in a public institution — and includes the John Singer Sargent Archive. Sargent claimed both Boston and London as his home, and together, the MFA and Tate Britain have served as guardians of the artist’s legacy.

Following its presentation at the MFA, “Fashioned By Sargent” will travel to Tate Britain, where it will be on view from February 21 through July 7, 2024.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is at 465 Huntington Avenue. For information, 617-267-9300 or www.mfa.org.