“Blossoming” by Milton Avery, 1918. Oil on board, 11 by 15 inches. Milton Avery Trust. ©2021 Milton Avery Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

HARTFORD, CONN. – Milton Avery has always been a paradox. His late-blooming career broke across several key moments in the development of American art, but his work has never fit comfortably into any particular movement. He is known, broadly speaking, as an abstractionist, and yet he remained grounded in the observed world and rarely painted anything that wasn’t right in front of him. Perhaps most surprising, this quintessential New York artist actually spent most of the first 40 years of his life in Hartford, Conn., which is where museumgoers and lovers of Modern art can see the first retrospective of his work in 30 years, at the Wadsworth Atheneum through June 5.

Avery is probably best known for his highly abstracted figure paintings of the late 1940s-50s, works like “Poetry Reading” (1957) that marry color and form in a way that is both utterly absorbing and definitively modern. It requires something of a recalibration, then, to realize that he was born in 1885 and that he came of age in an era when American Impressionism still dominated. Indeed, Avery’s earliest works – a remarkable number of which are included in the present exhibition, thanks to the family’s deep archives – have a distinctly impressionist bent. Paintings like “Blossoming” of 1918 use broken brushwork and thick impasto to articulate lovely but unassuming landscapes like those being produced in Connecticut art colonies such as Old Lyme and Cos Cob.

This was no doubt the favored approach at the Connecticut League of Art Students, where Avery began to take free classes (held at the Wadsworth Atheneum) in 1905, and he seems to have been content at that point to simply observe and learn. Avery was from a solidly working-class family, and while it was clear to him and those around him that he had artistic talent, he had little to no context for the history and practice of the fine arts before beginning his studies. He took classes at the league for 13 years, through 1918, before beginning formal instruction at the School of the Art Society of Hartford, all while working full-time in the city’s various industries – manufacturing and insurance, moving from the assembly line to desk jobs. Increasingly, he identified as an artist and began to rack up awards and recognition before finally moving to New York in 1925.

“Poetry Reading” by Milton Avery, 1957. Oil on canvas, 44 by 56-1/8 inches. Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Museum of Art, Utica, N.Y. ©2021 Milton Avery Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. Photo ©2021 Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute/Art Resource, New York City.

It is interesting to think of this methodical, incremental advancement in the context of his later work. Avery was an innovator, and his mature paintings are unlike anyone else’s, and yet at no point did he burst upon the scene with work that sought to redefine what art is or call into question the very nature of painting itself. He was more of a worker than a disruptor, researching and fine-tuning his approach through experimentation, testing and streamlining.

Soon after Avery relocated to New York, he was joined by his new wife, the artist Sally Michel, whom he had met on a painting trip to Gloucester, Mass. Michel’s commercial work supported the couple as they put down roots in the city, and Avery’s work from this time conveys the delight they found in their new home and their loving partnership. “Studio View (Chop Suey)” is the view from their apartment in a low-rent artists’ building on the Upper West Side, a “lovely celebration of the urban environment,” says Wadsworth Atheneum curator Erin Monroe.

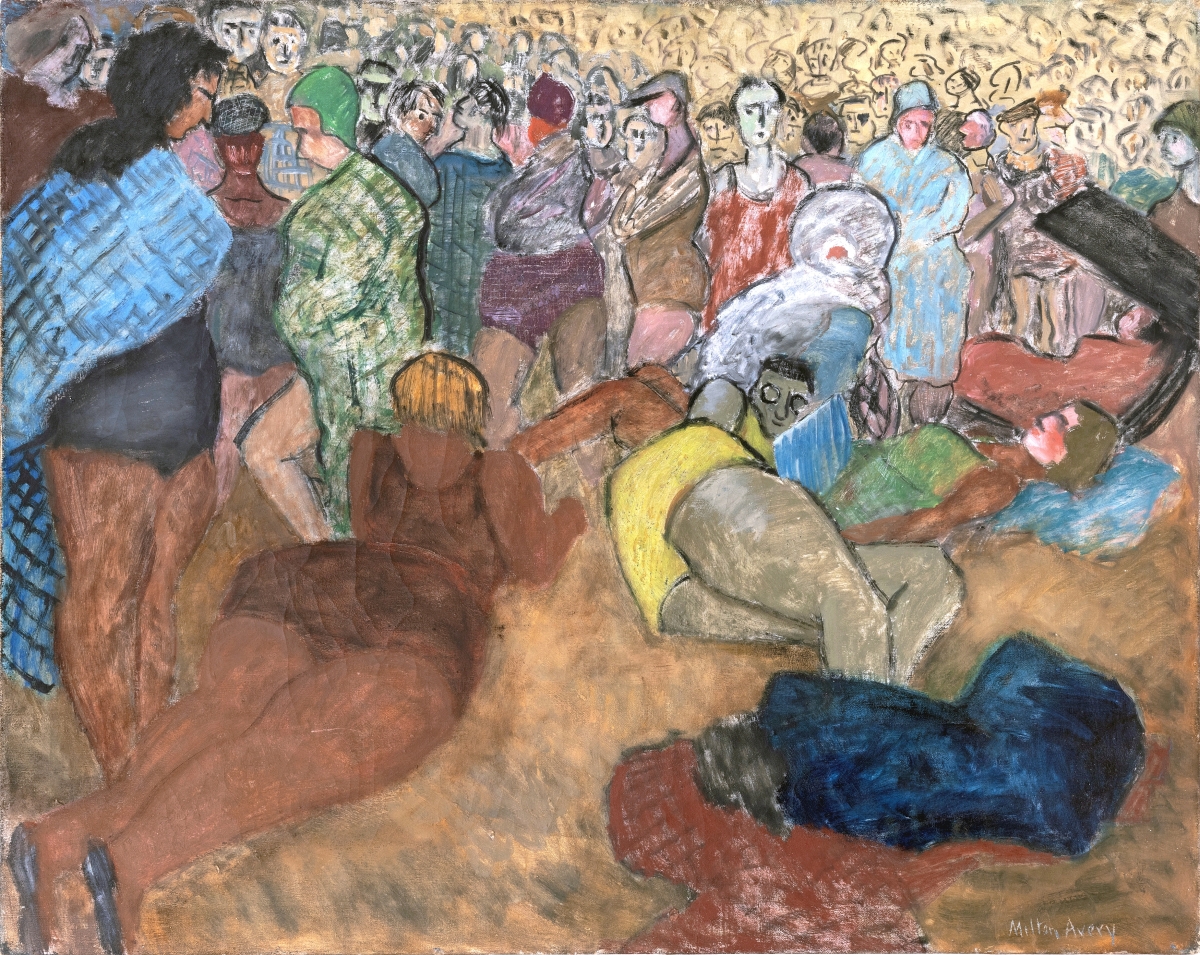

This and other works from this time, when Avery was experimenting with various approaches and trying to find his voice as a painter, are reminiscent of the so-called Ashcan School of painters who were his peers: George Bellows, George Luks and Reginald Marsh, among others. Like them, he reveled in New York’s teeming masses living their lives in the modern city. A small group of theater scenes, for instance – the brightness of the lights, costumes and bare flesh set against the darkness of the auditorium – recalls Luks’ and Marsh’s decadent paintings of burlesque performances. “Coney Island” of 1931 seems like it could have been compositionally inspired by Bellows’ already-famous “Stag at Sharkey’s” of 1909, with its three central figures surrounded by blurred and progressively faceless throngs.

Another Coney Island work of the same year, “Seaside, “is remarkably prescient of the direction Avery’s work would go some 15 years later. But for a while yet, Avery would continue to take everything in and test out various approaches. There was a period of transmuting his interest in nature and landscape into a more modernist, regionalist approach, inspired by repeated trips to Gloucester as well as Vermont (“Moody Landscape,” 1931; “Blue Trees,” 1945), the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec (“Little Fox River,” 1942), and California. Avery and Michel’s daughter, March, was born in 1932, and Avery was, in Monroe’s words, “the proverbial road-trip dad” – although unlike most other dads, he would turn around and go back to the house if he realized he’d left his watercolor paper behind.

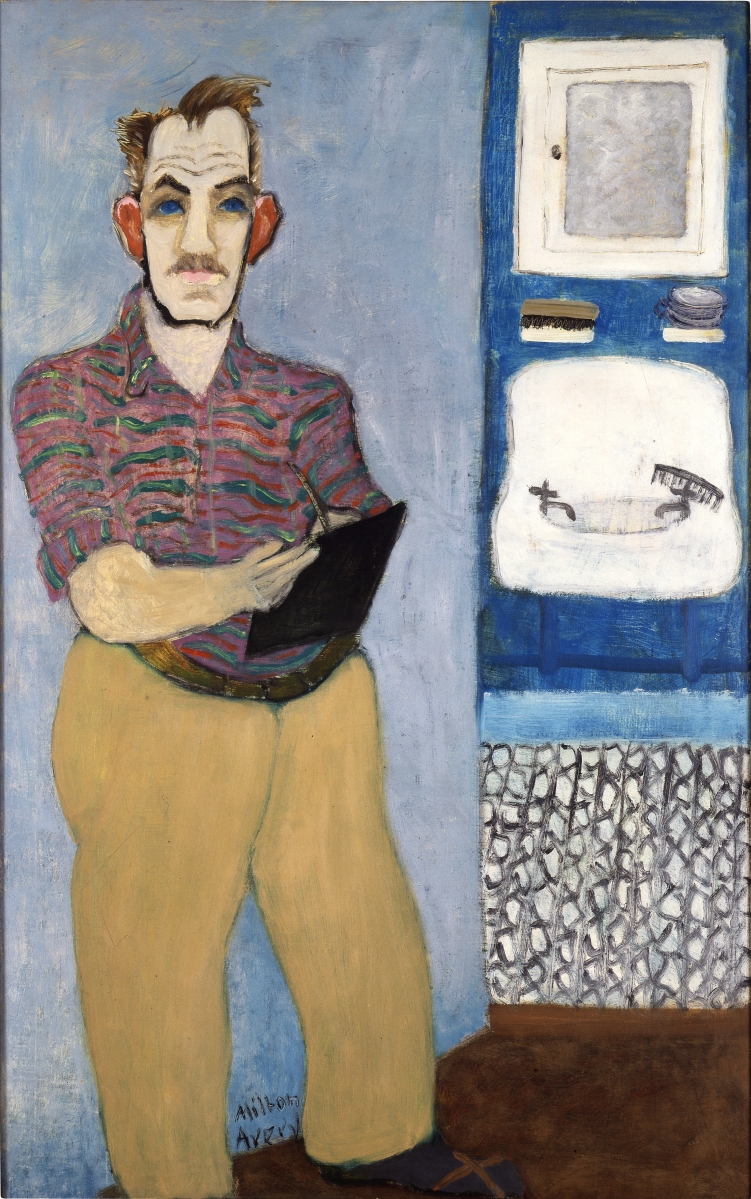

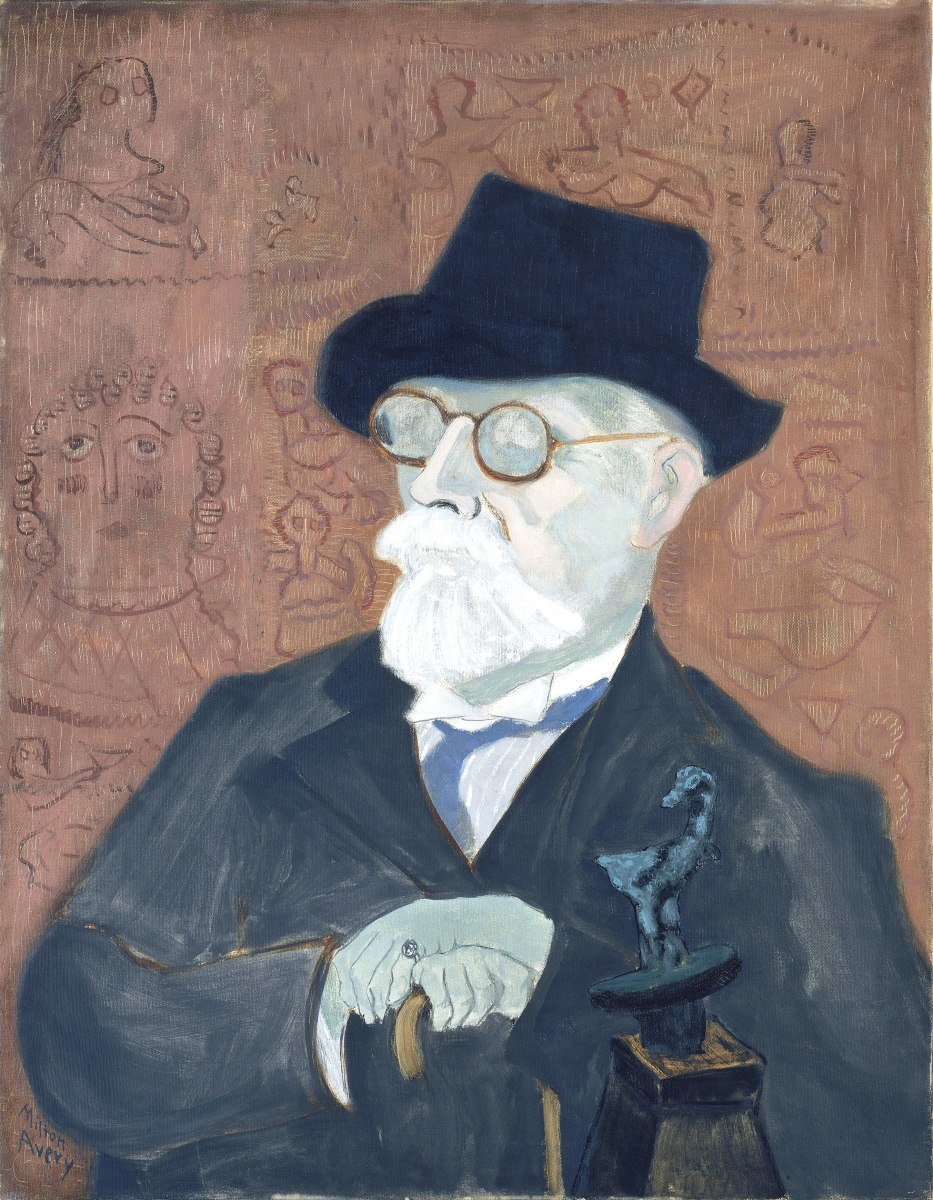

“Self-portrait” by Milton Avery, 1941. Oil on canvas, 54 by 34 inches. Collection Friends of the Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York. Gift from the Estate of Roy R. Neuberger, EL 02.2011.11. ©2021 Milton Avery Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. —Jim Frank photo

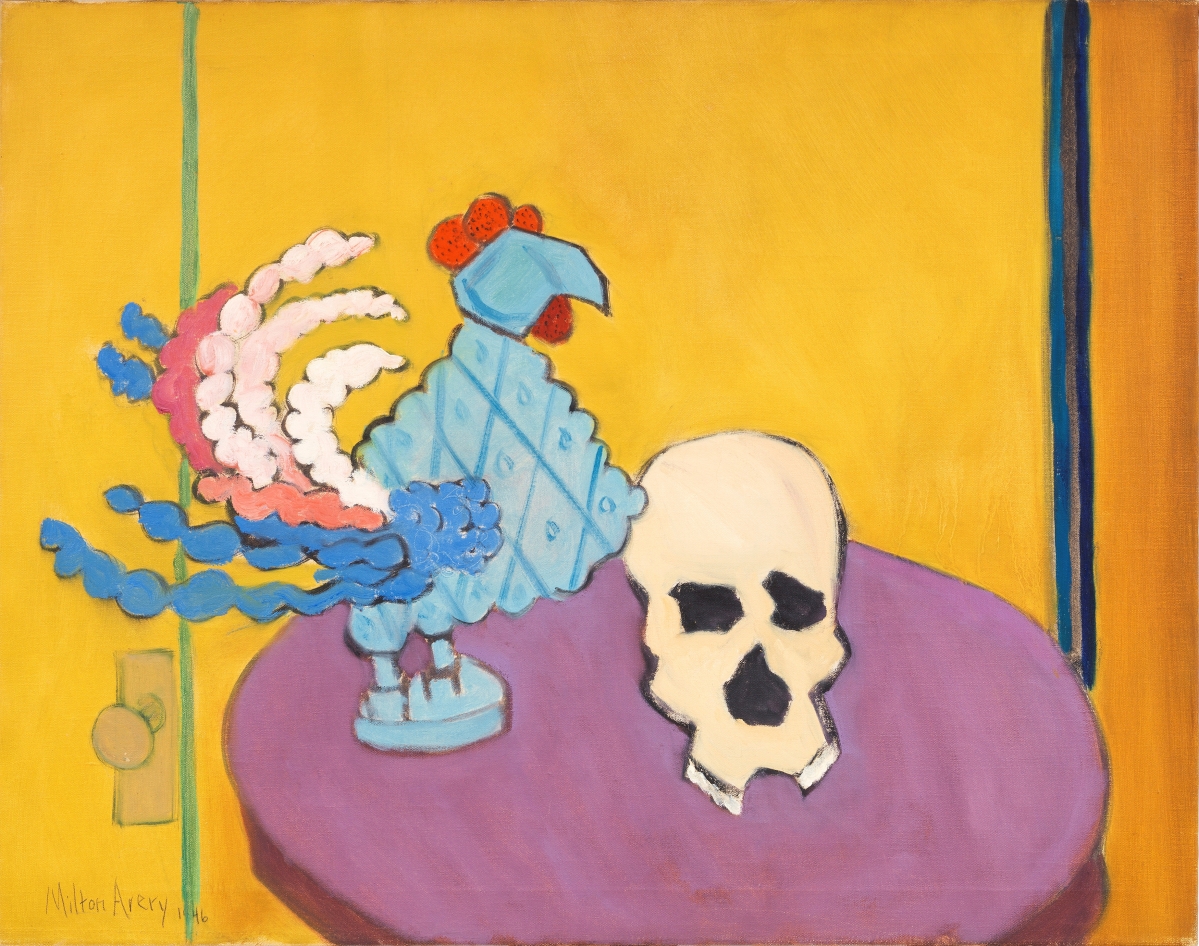

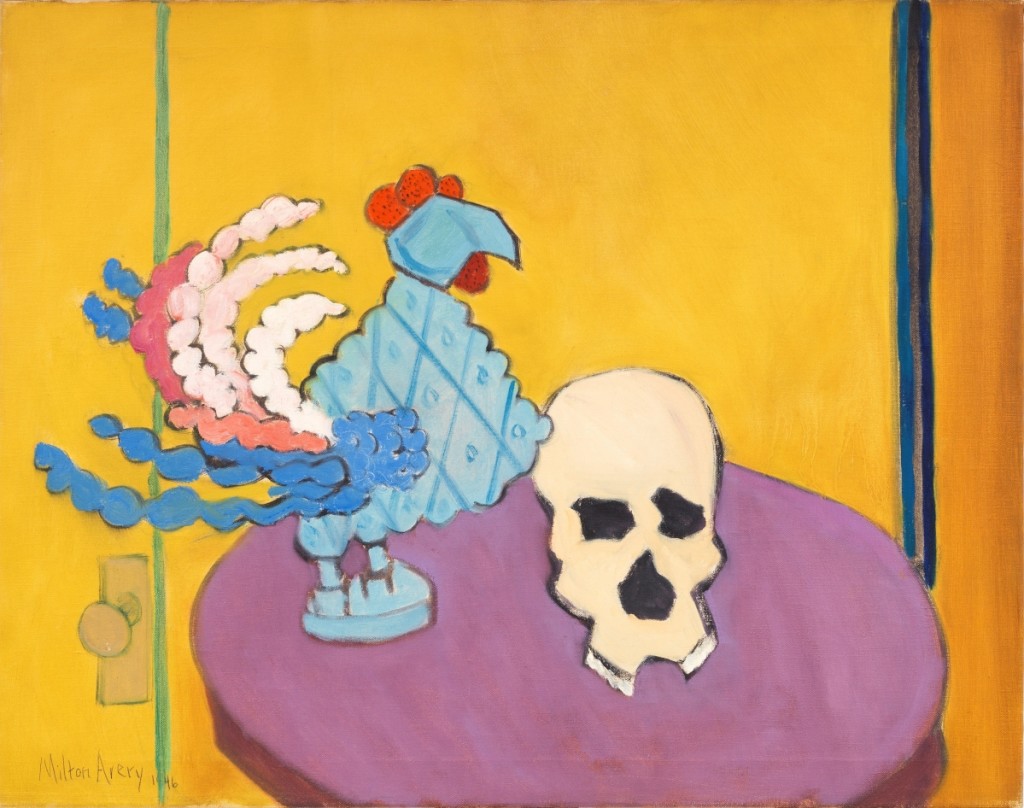

Around 1935, Avery joined the stable of artists at Valentine Gallery, which also represented heavy-hitters like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. The influence of these European modernists is apparent in works like “Still Life with Skull” (1946), which uses the same subject matter and compositional motifs as Picasso’s still lifes, if not necessarily his Cubist representation of space, and in the remarkable “Self-Portrait” of 1941, which wittily recasts the patterning, sophisticated coloration, and inside-outside elements of Matisse’s work from the South of France into the disheveled artist’s microscopic New York apartment. (The influence of Matisse in Avery’s work is the topic of an essay in the catalogue by Marla Price.)

Just as Avery looked to what preceded him and found inspiration there, he also looked to the next generation of painters and saw a future for art in America that held a place for him. Since the 1930s, he had been friendly with artists who would eventually become game-changers in Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting: Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. Avery hosted an informal salon with them that extended more than 30 years and moved from New York to Gloucester to Provincetown, Mass., depending on where Avery was working at the time. The monumental shift in Avery’s work in the late 1940s, however, is less about their influence on him than about this group of artists together entering a new chapter defined by the interests they shared: the layering of color, the simplification of form, the increase in scale, all of which would become defining features of postwar American art.

Monroe points out that Avery’s portraits provide the clearest illustration of this evolution. From his 1941 self-portrait, in which he mercilessly depicts his own physical traits in a convincingly three-dimensional space, he moves to “Dikran G. Kelekian” of 1943, an art dealer posed alongside the objects he sold, still an identifiable individual except for his blurred-out eyes. By “March in Babushka” in 1944, the background is completely gone, blending into the tied edges of the headscarf, and the figure, while recognizably March Avery, is little more than a series of abstract shapes in complementary colors, apart from some scratched-in lines to indicate features. Later that same year, in “Seated Girl with Dog,” March’s facial features are gone as well, her face and hair bisected into colored shapes to indicate the shadow cast by the light of the window.

“Still-life with Skull” by Milton Avery, 1946. Oil on canvas, 28 by 36 inches. Private collection. ©2021 Milton Avery Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

Works like these are tonal symphonies that read simultaneously as pure abstraction and gestural portraits of real people, real places, real moments in time. Here, the beloved daughter sinks her fingers into the glossy fur of the family’s cocker spaniel, Picasso, who nudges his nose affectionately toward the crook of her arm. Behind her, out the window, utterly invisible in reproductions, is the scratched-in outline of the fire escape across the way, the view the family saw every day. And yet, step back a few paces – either physically or mentally, or both – and the work is both complete and convincing as a total exercise in color and form.

The only one of the Atheneum’s own Avery works to be part of the touring exhibition appears in this section of the exhibition: “Husband and Wife” of 1945. This painting, too, demands in-person viewing, not only to appreciate the sgraffito details (eyebrows, bowtie, pipe) but also to experience the colors. More vibrant but also more nuanced than any reproduction, the pigments seemingly cover the in-between hues of the entire color wheel in complementary pairings: acid yellow with chalk-blue, sea-salt rust with moss green. “All of the colors have something to say,” Monroe observes, confessing that this long-familiar work remains her favorite among those on view. “To see it next to other works from that same period, which I’d never really done, helped me see it in a different light and helped me appreciate what was so incredible about…Milton Avery’s breakout moment.”

Here, too, are Avery’s famous nudes, clearly Matisse-inspired but more spare and economically expressed than any of that master’s works, as well as magisterial paintings like “Poetry Reading” and “March in Brown” (1954). One notable aspect of these works, compared to what had come before, was Avery’s remarkably restrained application of paint. Price writes in the catalog that Avery bragged he could make a tube of paint last longer than any other artist. The thinly painted surfaces helped him achieve the formal effects he wanted, but Monroe and Price also connect the technique to a certain sense of thrift, observing that he also painted on dish towels and the backs of other paintings (his own or not), and that his canvases were stretched with the absolute minimum amount of overhang. “He is a Yankee at heart,” says Monroe.

“Blue Trees” by Milton Avery, 1945. Oil on canvas, 28 by 36 inches. Collection Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York. Gift of Roy R. Neuberger, 1971.02.05. ©2021 Milton Avery Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. —Jim Frank photo

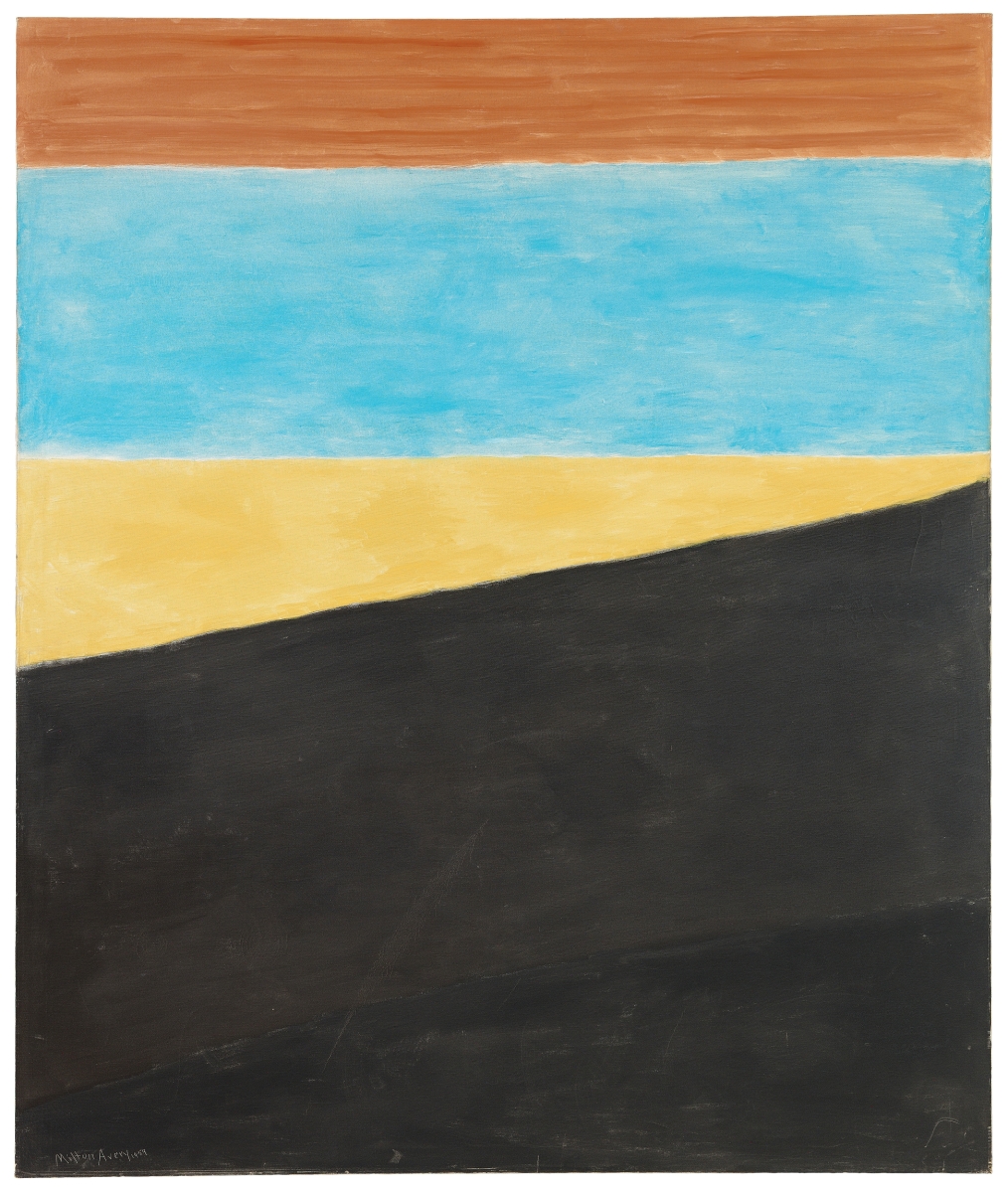

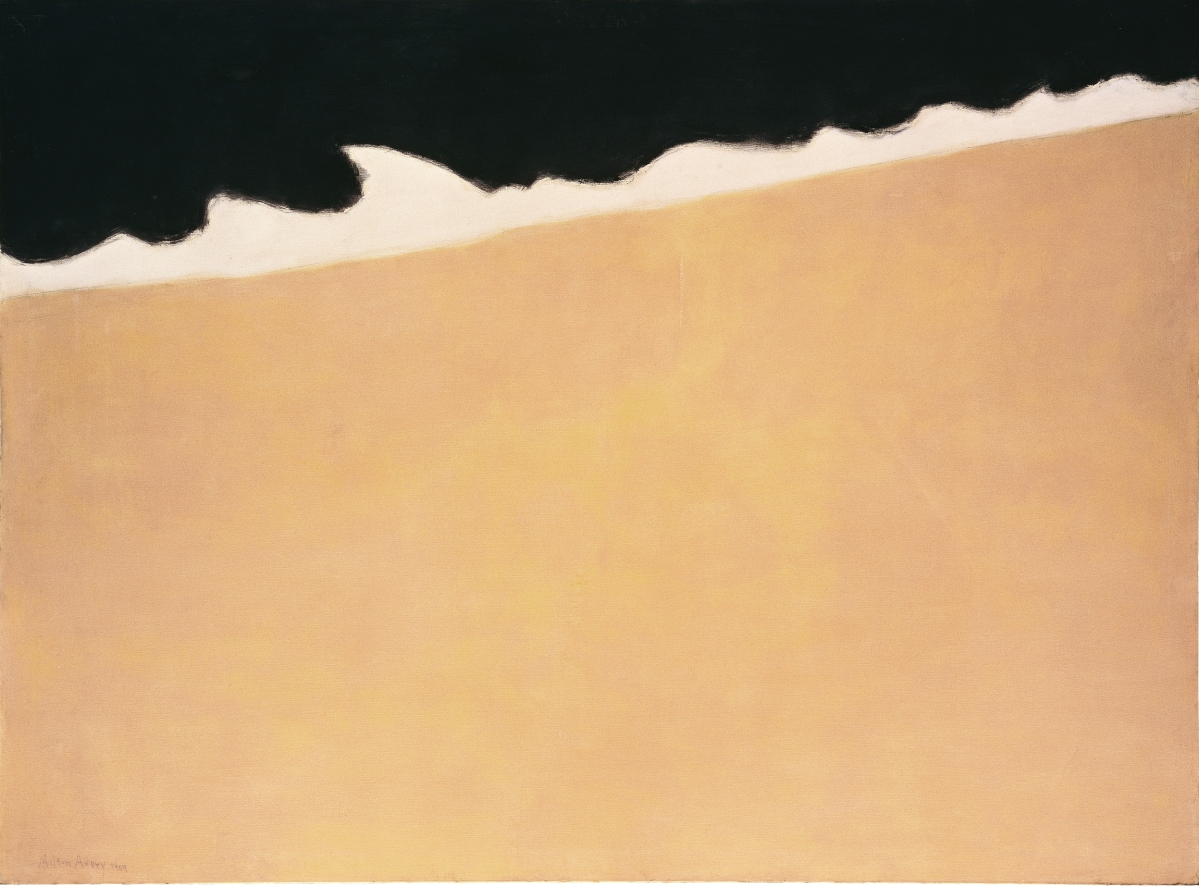

Avery had another burst of innovation in the last decade of his life (he died in January of 1965), when he was traveling frequently to Provincetown and spending time there in the company of his Abstract Expressionist friends, who had by then fully come into their own. “There is sort of a two-way conversation,” Monroe says, “and at one point, Avery says, ‘I started to paint on large canvases; I wanted to be like the abstract boys.'” The late canvases are indeed larger and more expressive than anything he’d done before that time – earning him the hard-won approval of Clement Greenberg, as well as other critical kingmakers – but they are still of things, real things, identified in the titles. The Provincetown shoreline is discernible enough in “Black Sea” (1959), with its slim crest of seafoam dividing sand and water, and “Sea Grasses and Blue Sea” (1958), a rarely seen work from the Museum of Modern Art that will only be on view in the Hartford venue of the tour. But even in “Boathouse by the Sea” (1959), which is composed of only four bands of orange, blue, yellow and black, once you know the title you cannot unsee the scene it depicts: an ocean view from the shadow of a beachside building. It is an abstraction, but on the other hand it isn’t at all, and in this way it and the other late works encapsulate the contradictions of this distinctive artist’s career.

That Avery’s workmanlike background and approach to his art undergirded such poetic creations was no doubt part of the reason he drew the attention of Edith Devaney of the Royal Academy in London, which originated the exhibition. It is a perfect art-school show, since Avery’s art education was both so foundational and so atypical, and yet there is deep relevance for the Wadsworth Athenaeum as well. “I would argue we’re probably introducing Avery to Hartford and Connecticut,” Monroe says, noting that he is not always included in lists of notable artists from the state. The fate of most artists is to be known in their hometown and not the world, but Avery’s situation has long been something of the opposite – just another one of the paradoxes this major survey seeks to explore.

The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art is at 600 Main Street. For more information, www.thewadsworth.org or 860-278-2670.

.jpg)