“Painter at Work,” House of the Surgeon, Pompeii, First Century CE. Fresco. National Archaeological Museum of Naples: MANN 9018. Image ©Photographic Archive, National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY – I don’t know if “Painter at Work,” the First Century CE fresco from the House of the Surgeon in Pompeii is the earliest image of a woman painting, but it’s the earliest I’ve seen. And, like every work in “Pompeii in Color: The Life of Roman Painting,” now on view at New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, it’s astonishing on a host of levels. That this work, and so many others, survived the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE and the subsequent burial of the city of Pompeii in volcanic ash and rock is, in itself a miracle. What’s more, it is one of the few places in archaeological history that shows us a culture in a particular moment in time. Contrast this with an essay I wrote for these pages not long ago on Stonehenge, where the challenge for archaeology is to make sense of a sacred place that witnessed many cultural changes over centuries of occupation – a condition that its more the norm in the field – and you’ll have some sense of the uniqueness of Pompeii.

But of the 35 or so frescoes in the exhibition, gleaned from a larger number lately on view in Oklahoma City, Okla., and all part of the collection of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, Italy, “Painter at Work” made me do a double take. Indeed, it is a work of deliberate doubling. “Painter at Work” is a painting of a painter painting a painting – held at an angle by a child so that we can see it – a painting not of an old man, but of a statue of an old man on a pedestal. The statue and the painting of the statue are mirrored by the pair of women – clients, perhaps, or patrons – at right, peering – peeking? – from behind a pillar, watching the painter at work. We watch the women watching the woman paint, just as those who resided in or visited the House of the Surgeon would have.

Excavations have gone on in Pompeii since early in the Eighteenth Century and show no sign of abating as fresh discoveries are made every year. The frescoes in House of the Surgeon, as an example, were unearthed in 1771. Though the walls of the room on which “Painter at Work” was painted are, as the sumptuous accompanying catalog states, in a poor state of preservation, drawings made in the 1770s, and subsequently published, offer a sense of the context of the work. In this case, “Painter at Work “was surrounded “by a complex decorative scheme with architectural side panels richly decorated with tritons, seahorses and the figures of donors…” (cat. p. 92) On the opposite wall, a fresco of a seated man, writing, while two women look on, surrounded by a similar decorative scheme is yet another doubling, celebrating the twin arts of painting and writing.

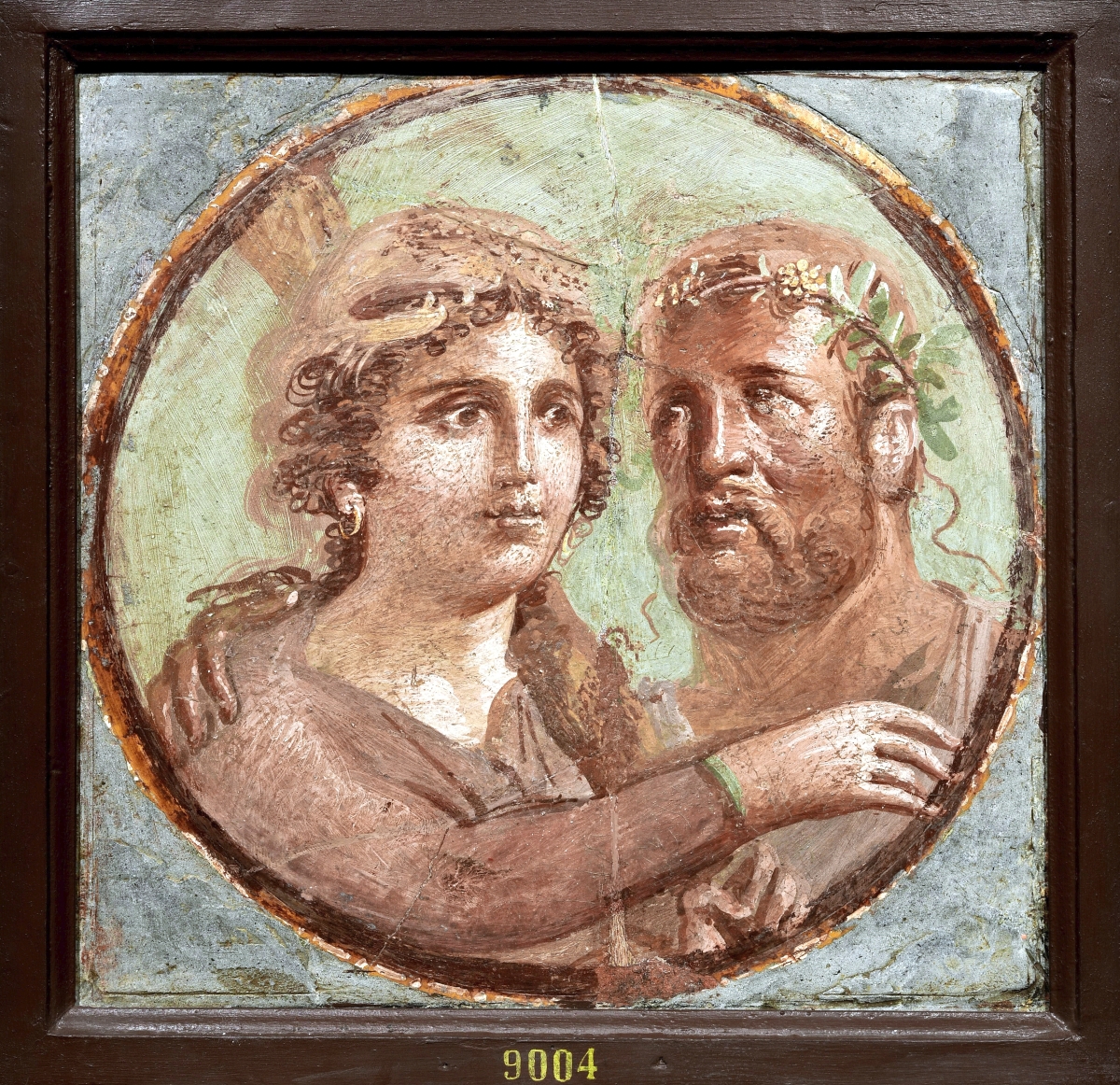

“Polyphemus and Galatea,” Villa at the Royal Stables on Portici, Pompeii, First Century BCE. Fresco. National Archaeological Museum of Naples: MANN 8983. Image ©Photographic Archive, National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Many frescoes, such as those in the exhibition, were removed from their walls and framed as paintings. Today, archaeologists leave the works in situ wherever possible. Context, which is a central aim of the exhibition, leads to stronger hypotheses about the anonymous artists who painted the frescoes, the patrons who commissioned them, the rooms they decorated, the relationships between the images, and, by extension, what they may have meant to those who lived with them, and what they may have meant to convey to those who visited. Perhaps those who dwelled in the House of the Surgeon fancied themselves as amateur painters and writers, or perhaps they wanted visitors to take note of their patronage of the arts. Or both. “Painter at Work,” taken out of context, is intriguing. Doubling is a figure or trope we generally associate with more recent artists and artworks – Diego Velasquez’s 1656 painting, “Las Meninas,” to name one. In its original context, however, as we envision “Painter at Work” opposite the fresco of the writer at work, the possibilities proliferate, and the work becomes a social statement as well as an artistic creation.

In terms of doubling, another fascinating aspect of “Pompeii in Color: The Life of Roman Painting” is the repetition of images of popular mythological stories in different houses, painted by different hands in different eras. Figures in these frescoes are similar to one another and are often positioned almost identically in the picture plane. This is difficult to describe in words, but easy to see when you look at the two versions of “Achilles on the Island of Skyros,” one from the House of Achilles, the other from the House of the Dioscuri.

The story of Achilles on the Island of Skyros is an apocryphal, Iliad-adjacent tale in which Achilles, not wanting to go to Troy, hides out at the court of King Lycomedes on the Island of Skyros. When Ulysses and Diomedes come to fetch him, he appears, dressed as a woman. When Ulysses, ever the crafty Greek, has a soldier sound the call to battle on a trumpet, Achilles reflexively grabs his swords and shield and reveals his identity. In the two renderings, the central grouping – Ulysses at right, grasping Achilles’s arm, Achilles placed in the center, right hand on the shield, looking back at Diomedes, who grabs Achilles’s right arm. Despite losses to the House of the Dioscuri version, there are other congruities in the background figures, columns and architectural details, and in the objects on the floor in the foreground. Both shields, for example, depict young Achilles and his teacher, Chiron the centaur.

Installation view from “Pompeii in Color: The Life of Roman Painting,” 2022. Image ©Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. —Andrea Brizzi photo

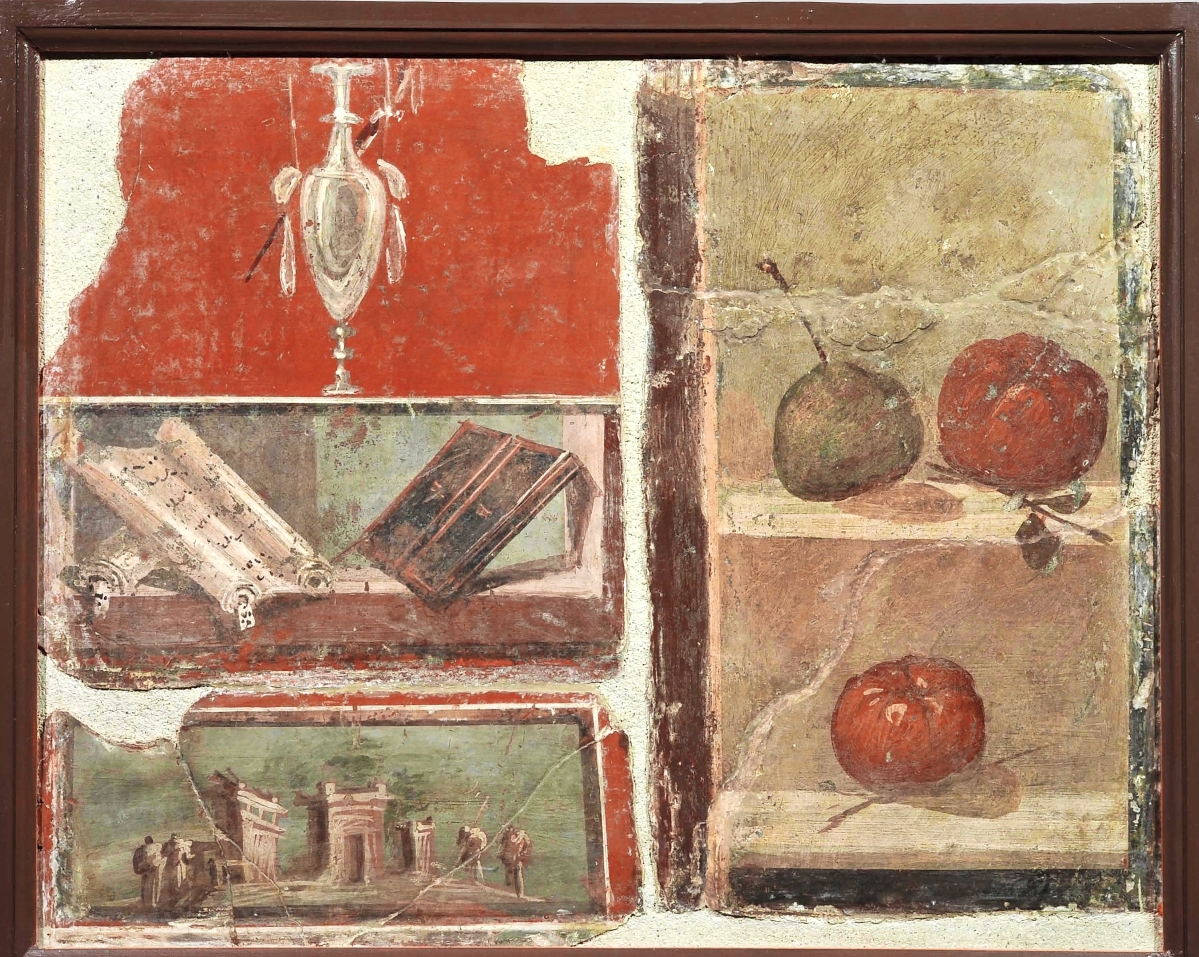

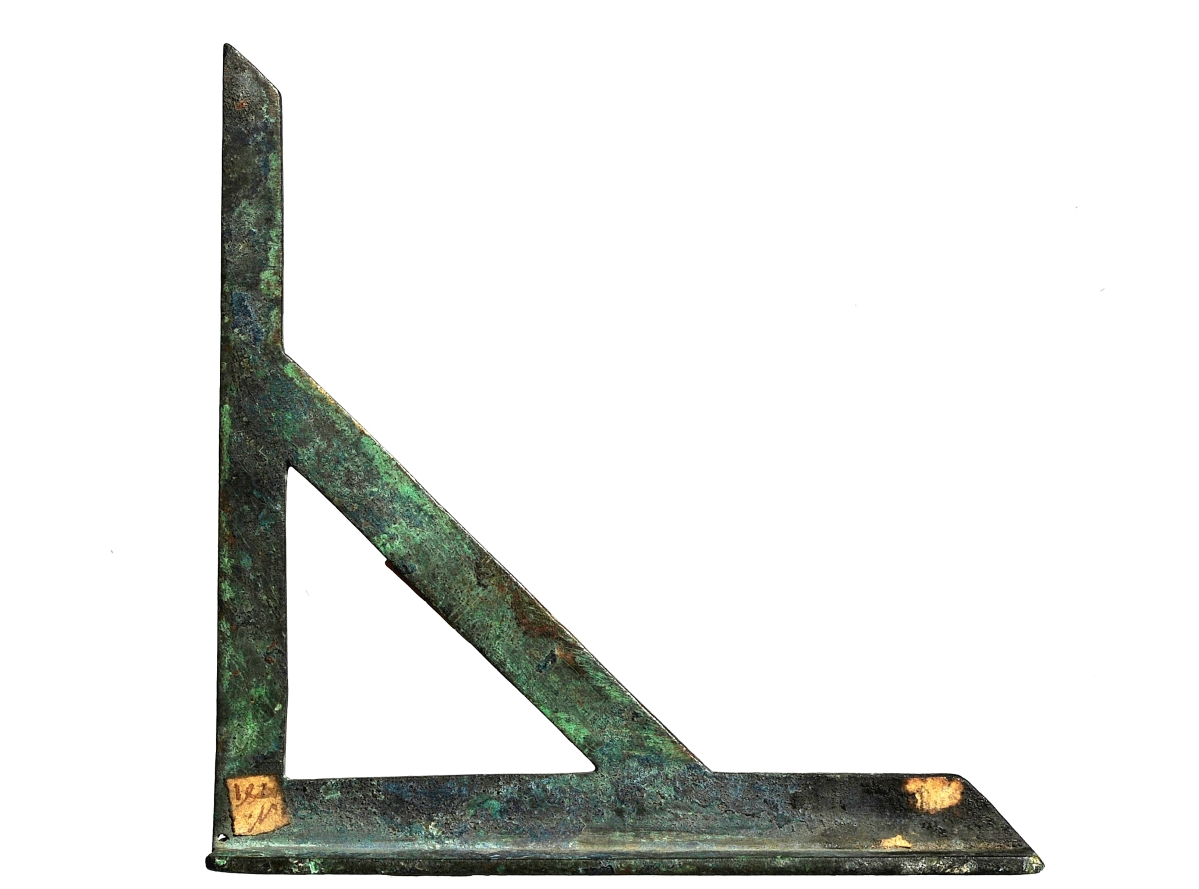

All of this begs the question: how did Roman fresco painters paint, and how did they create these “copies?” One of the rooms in the exhibition recreates, in part, a story of painters leaving their work and fleeing as the eruption of Vesuvius begins. A fragment of wall retains an artist’s drawings and a grid red line achieved by snapping a pigment-covered string against the wall. Recovered plumb bobs and set squares show how artists measured the area and made sure the grid squares were identical and square. Cups of pigment, also recovered, match the cup in the hand of the “Painter at Work.” As for the images themselves and their curious copying, scholars surmise that this may have been achieved in four ways, none of them mutually exclusive:

“1) from a model-book that captured all the details of a particular painting; 2) from an outline-book that was like the model-book but recorded only the outlines of figures and backgrounds; 3) from a figure-book with sketches of individual figures or simple groups; 4) from memory.” (cat. p. 38.) It would have been relatively easy to transfer images from a book onto a gridded wall, make adjustments based on the space and surrounding decorations, and then add one’s own style to the fresco. Despite their anonymity, this sort of coordination is suggestive of teams of painters, perhaps workshops or guilds. It also suggests that people may have visited one another, liked the paintings they saw, and commissioned versions for their own homes.

On reflection, certain works stand out. The sulfurous yellow and red tones glazing “Architectural Landscape” from the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum, turn out to be the direct result of exposure to the sulfurous fumes of Vesuvius. At the top of the stairs, a ghostly shape is sometimes thought to be a person with, perhaps, a dog. A half-vanished abstraction, the almost formless form is an eerie apparition within an apparition.

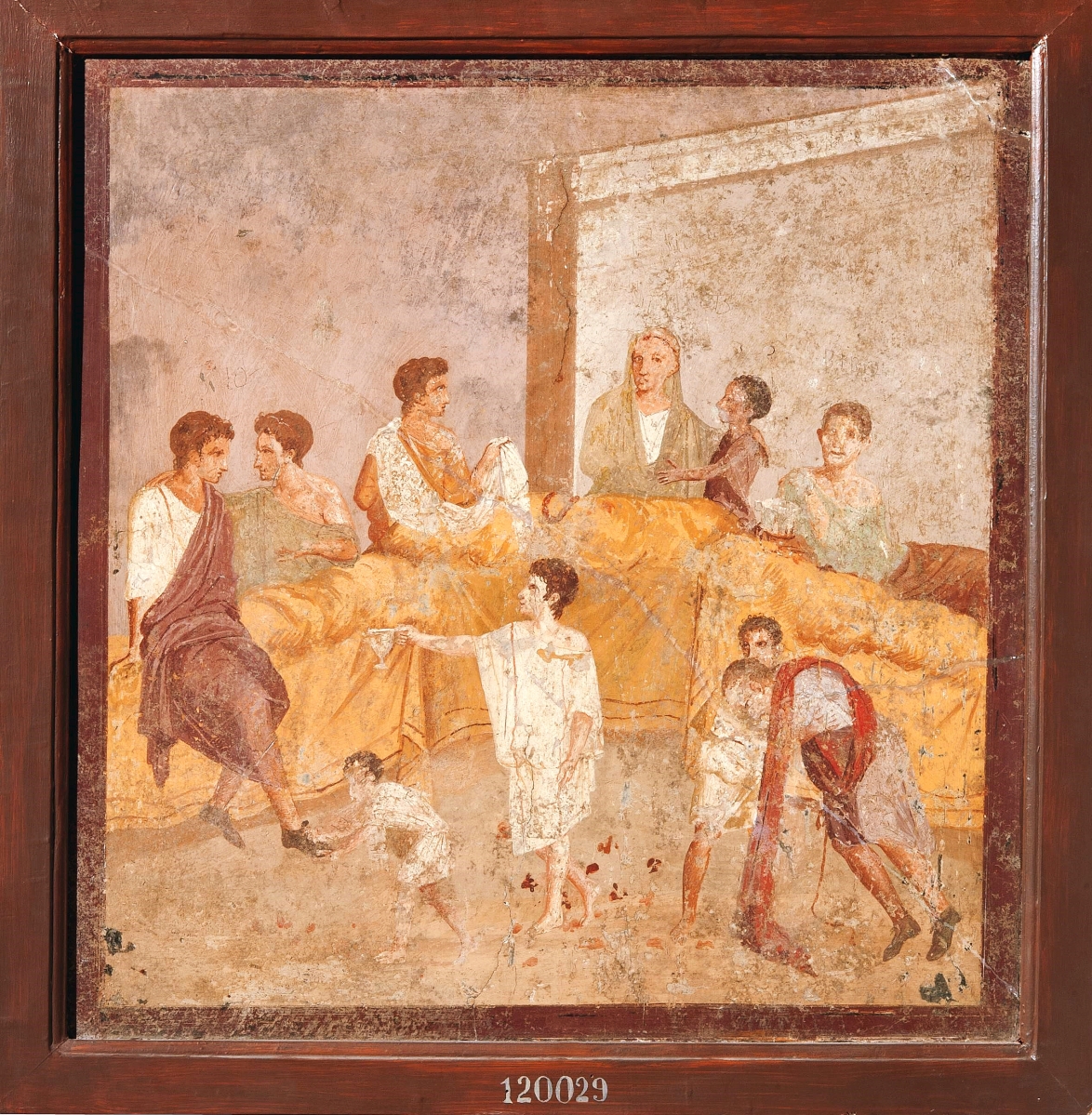

Humor leavens the tragedy of the end of Pompeii and reveals another side of Roman life and thought. “Banquet Scene,” or “Symposium,” from the House of the Triclinium, Pompeii, depicts people at the beds in the triclinium, or dining room, covered in cloth as they chat, flirt, drink, serve and vomit. It is the moment near the end of the party when the bad behavior has just begun. As a bonus, legible words in Latin, thought to have been added before the eruption – of the volcano, not the party guest – are scratched in above the figures. The one above the figure at right reads “Bibo” (“I drink”). At center, “Valetis” (“Be well”) seems to refer to our friend who has overindulged. Besides that, “Isisa” may well be the name of a guest of someone in the household. That this fresco was painted in a dining room suggests that it is a mirror of sorts, a humorous yet cautionary tale against exactly this kind of party, one that leaves a bad taste in your mouth.

Architectural landscape, Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum, First Century BCE. Fresco. National Archaeological Museum of Naples: MANN 9423. Image ©Photographic Archive, National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

The age-old art history myth holds that Roman art was comprised of debased copies of lost Greek masterworks. Greek artists did work in Rome and did inspire Roman artists, even in Pompeii, but a quick comparison of the works on these pages with images of Hellenistic art shows that in almost aspect, Roman art went its own way. From stories, like the one of the timorous Achilles in women’s clothes who can’t resist the battle blare, to the playful notions of doubling, to painting architectural details in trompe l’oeil fashion, to the very human humor and pathos – foibles leveling gods and humans – depicted in the frescoes, Roman art represents the Roman world as Romans saw it.

I had the distinct pleasure of a tour of “Pompeii In Color: The Life of Roman Painting” with Dr Clare P. Fitzgerald, Bernard and Lisa Selz exhibitions director and gallery curator at ISAW accompanied by my daughter, Lucia. Lucia and I have followed events at Pompeii ever since we read Vacation Under the Volcano – one of the Magic Tree House books for kids – in which Jack and Annie find themselves in the doomed city just days before the eruption. Like Jack and Annie, Lucia and I urge you to run, run as if a river of lava were chasing you, to see “Pompeii In Color: The Life of Roman Painting.” ISAW is a stone’s throw from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. You won’t regret the quick detour or the extra time it takes to see this once-in-a lifetime exhibition.

“Pompeii in Color: The Life of Roman Painting” will be on view through May 29 at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University, at 15 East 84th Street. For information, 212-992-7800 or www.isaw.nyu.edu/exhibitions/pompeii-in-color.

EDITOR’S NOTE: At 4 pm EDT on Thursday, June 9, the author of this story, James Balestrieri and Dr Clare Fitzgerald, will be participating in a virtual salon titled “The Working Artist in Antiquity.” To attend, click clarkhulingsfoundation.org/chf/salons/.