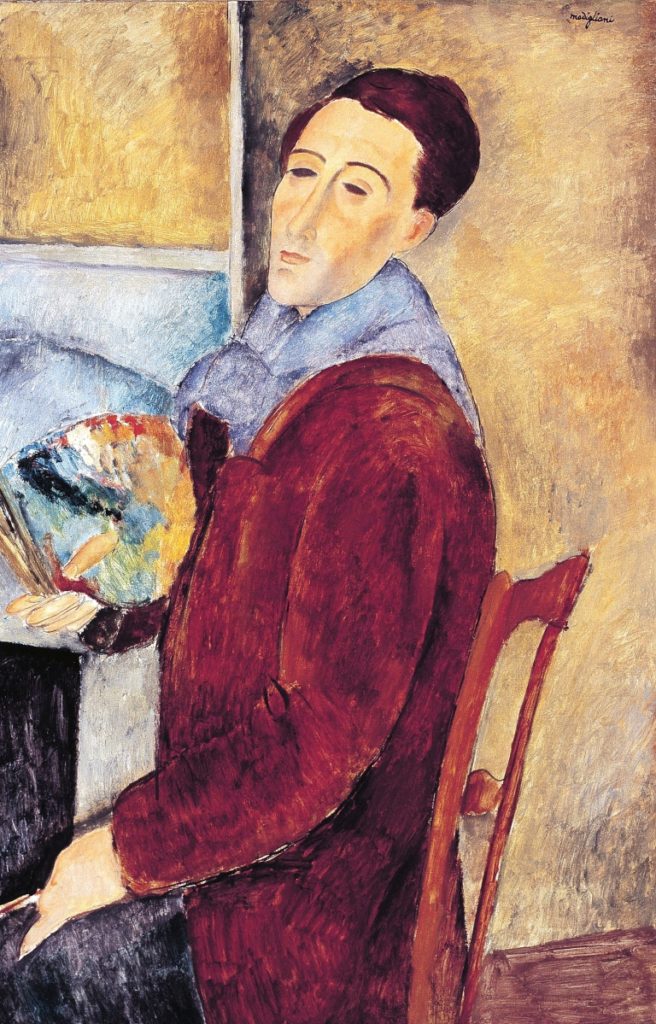

“Self Portrait” by Amedeo Modigliani, 1919. Museu de Arte Contemporanea da Universidade de São Paulo, Gift of Yolanda Penteado and Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho. MAC USP Collection [Museu de Arte Contemporânea da USP Collection, São Paulo, Brazil].

By Kristin Nord

PHILADELPHIA – On the surface, Amedeo Modigliani’s (Italian French, 1884-1920) paintings appear deceptively simple; and forgers throughout the past 100 years have flooded the art market with works bearing his name. His elongated figures have long fetched stratospheric prices at auction, and the absence of a full and accurate inventory of his works has opened the gates to charlatans for a century.

In “Modigliani Up Close,” on view at the Barnes Foundation through January 29, efforts to set the record straight are firmly underway. By putting some 47 major works through their paces, the exhibition reveals the tools with which experts are hard at work deconstructing the artist’s materials and working methods.

Organized by a team of curators and conservators that includes, from the Barnes, Barbara Buckley, senior director of conservation and chief conservator; Simonetta Fraquelli, consultant curator; and Nancy Ireson, deputy director for collections and exhibitions and Gund Family chief curator; and Annette King, paintings conservator at Tate, London – the show builds upon the herculean research project that began in 2017 and led to a major retrospective at Tate Modern in 2018.

While technical analysis has become a significant tool in understanding the work of contemporaries Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse, the curatorial team notes, it is particularly important in understanding Modigliani, whose work to this day lacks a comprehensive catalogue raisonné.

“Head” by Amedeo Modigliani, circa 1911. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Mass. Gift of Lois Orswell. Photo ©President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Though this team asserts that “close looking” remains the quintessential tool in any art historian’s kit, X-rays, infrared reflectography, ultraviolet photography, light microscopy and paint chemical analyses using X-ray fluorescence have become increasingly important in establishing authenticity. And the Barnes Foundation, which holds one of the largest Modigliani collections in America, has tested its own Modiglianis using the latest tools available.

The artist was born into a genteel Sephardic Jewish family in Livorno, a major port on the Ligurian Sea. He was already drawing upon a cultured background and academic training when he settled in Paris in 1906. It was there he found Europe’s artistic capitol teeming with avant-gardists and where non-European and prehistoric artworks, often looted from Indigenous sites in the French colonies, were readily viewed.

He initially dedicated himself to sculpting, and for three intense years, between 1911 and 1914, he created a series of stylized and androgenous heads. His primary material was limestone, which he probably bought from stonemasons or culled from worksites.

In approaching these sculptures, Modigliani preferred to make preparatory drawings and then cut directly on stone, letting the carving determine the form. He often left portions of the blocks unfinished, showing the marks of his carving tools. With support from his early patron, Dr Paul Alexandre, who shared his passion for antiquities and African and Oceanic material culture, he created works distinct for their elongated necks and noses and lidless eyes.

“The Pretty Housewife (La Jolie ménagère)” by Amedeo Modigliani, 1915. The Barnes Foundation.

“Modigliani’s heads are all highly stylized, with inspiration having come from far and wide,” Jessica Fertig, Christie’s New York’s senior vice president of Impressionist and Modern art, commented recently in a Christie’s newsletter. “They’re best seen as an elegant fusion of elements from Egyptian, Khmer, Cycladic, early Christian and, above all, African sculpture – specifically, Baule figures from the Ivory Coast and Fang masks from Gabon.”

Seven of Modigliani’s sculpted heads have been mounted in the round for this exhibition and they make for commanding presence, from a smiling head believed to be his earliest work, on loan from the Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Art Museum, to a second head, held by the Barnes, whose elongated face and neck is framed by two projections that appear to be tears. The artist’s tool marks and process of drawing, carving and reworking can be seen in each.

Those on loan from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the National Gallery of Art were featured in his early exhibition at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1912. Taken together with heads from the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden at the Smithsonian Institution, the Museum of Modern Art, The National Gallery of Art, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, they are extraordinary examples of the artist’s early mastery of the form.

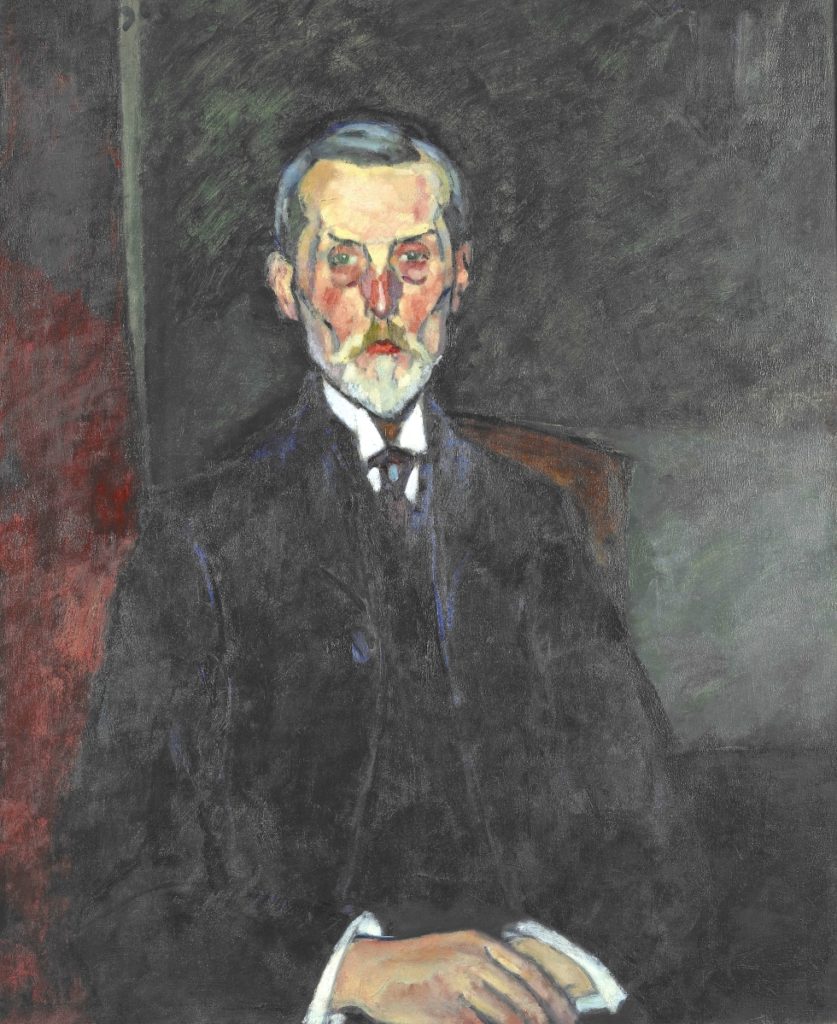

Transmitted light photograph showing the thinness of the paint layer in “Portrait of Roger Dutilleul” by Amedeo Modigliani, 1919. Collection of Bruce and Robbi Toll.

Modigliani’s sculpting career was cut short when he found the dust from his carving was seriously compromising his health. He suffered from tuberculosis and pleurisy for most of his life, and he would die of tubercular meningitis in 1920. Yet, Fertig cautions, “It would be entirely wrong to think of Modigliani’s sculptures purely in relation to his paintings. Many accounts from those who knew the artist attest to just how seriously he took his work in three dimensions.” And his skills at sculpting could be seen in some of the innovations he made as a painter.

One curious aspect of his efforts during these years of shift in media was his penchant for painting on top of already finished paintings. “While it is tempting to attribute the practice to the artist’s lack of funds for buying new materials,” the curatorial team writes, “it is likely that in some instances Modigliani enjoyed the challenge of covering older works or used the underlying colors and textures to enhance aspects of the new painted image…”

“The Pretty Housewife” (1915, The Barnes Foundation) shows through x-radiography that two and possibly three earlier paintings preceded the finished work. Modigliani used the complex colors beneath the surface actively, as when he painted a wicker basket over a variety of existing colors and textures to create the illusion of contents.

In “Jean-Baptise Alexandre with a Crucifix” (1909, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen), an x-radiograph, similarly, reveals an underlying portrait. In this work the artist’s virtuosity as a colorist is evident as he paints what appears to be the pharmacist’s black jacket from a complex mix of pigments.

“Jean- Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix” by Amedeo Modigliani, 1909. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Gift of Blaise and Philippe Alexandre, Image ©C. Lancien, C. Loisel /Réunion des Musées Métropolitains Rouen Normandie.

If Paul Guilliaume, the artist’s first dealer, had been instrumental in Modigliani’s return to painting, his introduction to the Polish dealer Léopold Zborowski, too, became an important influence on the artist’s choice of subject matter and materials. From this point forward he used commercially produced canvases, often with a blue-grey colored priming. The colored grounds gave the works a warm glow and were the basis for the series of nudes he produced thereafter.

“Nude with Coral Necklace” (1917, Allen Memorial Art Museum), “Reclining Nude from the Back” (circa 1917, The Barnes Foundation) and “Nude” (circa 1919, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), remain provocative explorations of female sexuality. No wonder these and “Nude (1917),” one of seven nudes in the show, jolted then-prudish Parisian society (in 1955 the latter was still causing a stir when it appeared as a reproduction postcard for sale in the Museum of Modern Art’s gift shop). “But if there is a compositional sameness to the reclining nudes Modigliani produced between 1916 and 1919, there is remarkable variation in terms of the physical features of their individual bodies,” the curatorial team writes.

During his sojourn from 1918 to 1919 in the south of France, the artist once again modified his portrait subjects and his palette. He turned to experimenting with white grounds, tempera and diluted paint to better capture Mediterranean light. And he captured a succession of country people and children, and produced luminous portraits of Jeanne Hébuterne, his muse and lover.

“The Young Apprentice” (Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris) dates to this intensely fertile period (circa 1918-19). The artist had made a very thorough drawing of the portrait, and x-radiography shows he was faithful to the drawing but made modifications to the size of the young man’s head and strands of hair on his forehead. He used impasto brushstrokes to create interesting textures; while the hands and forehead were executed with thick paint layers, the flesh tones of his face were much more thinly painted.

Jeanne Hébuterne was probably in the first or second trimester of her second pregnancy when the artist captured her in a white chemise (circa 1919, The Metropolitan Museum of Art). She appears both simultaneously timeless and modern – her left arm draped upon an upholstered chair and her face framed by a finger. Infrared reflectography reveals “the fluidity with which the artist drew her form”; an X-radiograph shows the revisions he made to the placement of her nose, eyes and chin. On some level, one can’t help but marvel on the ways in which Modigliani’s creative growth appears mirroring the growth of their unborn child.

“Reclining Nude from the Back (Nu couché de dos)” by Amedeo Modigliani, 1917, oil on canvas. The Barnes Foundation.

“Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater” (circa 1918-19, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum) offers yet another view of the mother-to-be, this time in the late stages of her pregnancy. It glows, with its yellows and blues harkening to early Quattrocentro painters, who turned to gold leaf and lapulazuli for depictions of holy subjects.

Dr Albert C. Barnes was one of Modigliani’s earliest American collectors, and it seems fitting that “Modigliani Up Close” is having its only appearance here. Barnes had collected 12 paintings, three works on paper and one carved stone sculpture in the early 1920s, seeing immediately in Modigliani’s art kinship to objects from colonial West Africa. He played a major role in shaping the artist’s critical reception in this country. The Barnes’ Modiglianis remain in-situ in the foundation’s permanent galleries, arranged in the vignettes Barnes designed for teaching purposes.

The exhibition begins with the artist’s self-portrait, created in 1919 shortly before his death. It is a masterful painting in which the colors on the palette he is clutching match the pigments in the composition itself. “From the painstaking drawing and painting of his own facial features to the looser depiction of his hands holding the tools of his trade, curators at the Museu de Arte Contemporanea da Universidade de São Palo, which acquired the painting in 1963, note, “Everything in this painting represented the artist’s choice of how to portray himself.”

“We do not know which direction Modigliani’s art would have taken had he lived beyond the age of 35, but we can see in his later portraits the visual ingredients of what would become the ‘return to order’ in European art after the war: a respect for proportion, an adherence to figuration and a preference for balance and solid form,” the exhibition’s curators write. His was art that was grounded in the past, they said, “but looking firmly to the future.”

The Barnes Foundation is at 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway. For additional information, www.barnesfoundation.org or 215-278-7000.