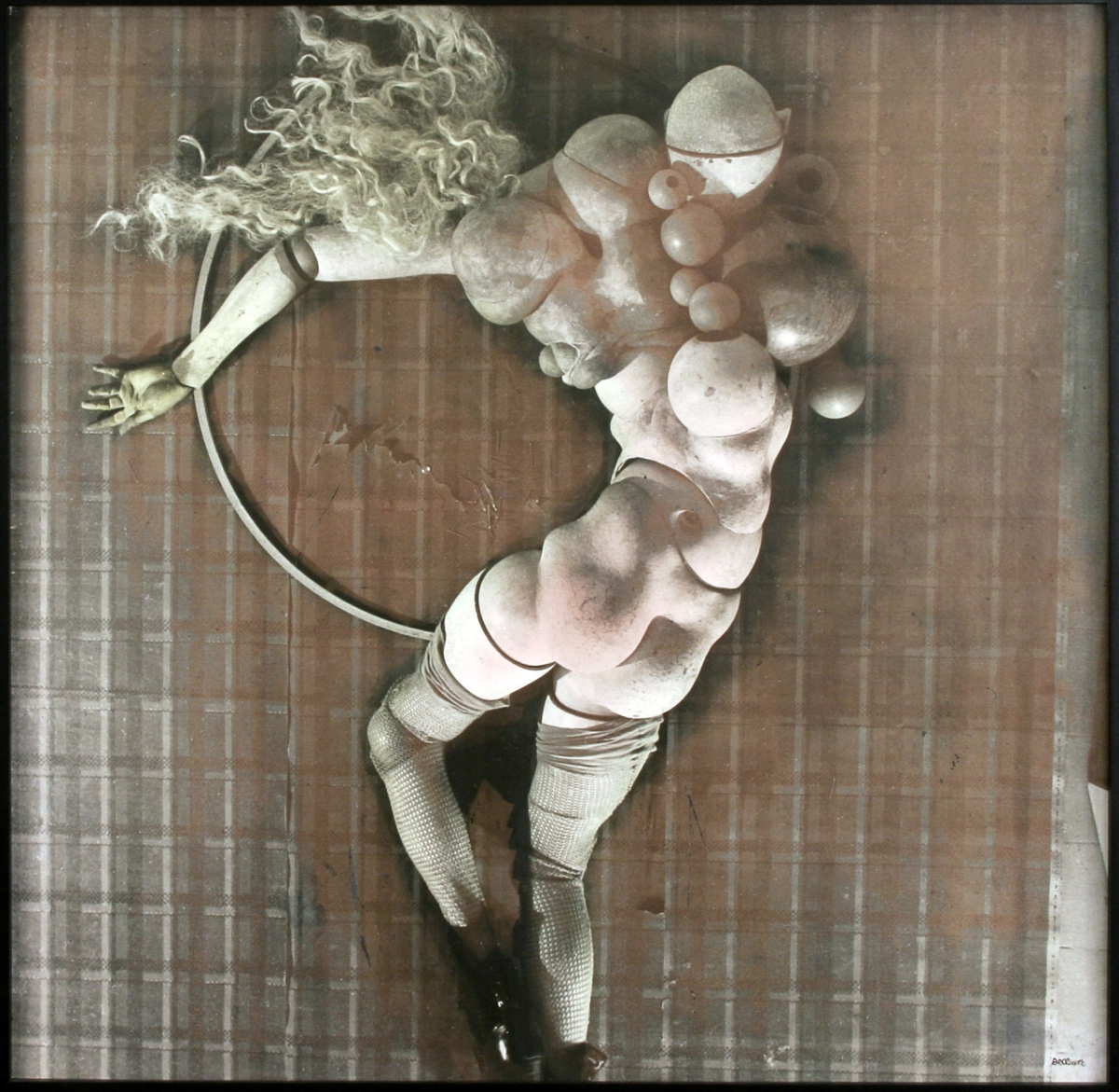

“Tauromachie” by André Masson, 1937. The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Cone Collection, formed by Dr Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Md. ©Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

BALTIMORE – The Minotaur – the fearsome half-man, half-bull monster that haunts the center of the labyrinth in Greek mythology – is one of the most recognizable tropes of the Surrealist art movement. Simultaneously strong and terrifying, yet blind and vulnerable, the Minotaur captured the anxieties of a new century rent by conflict. Surrealism, which was formalized by the French artist André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto of 1924, is most often associated with the period between the two World Wars. Less recognized is the extent to which Surrealist artists were active during wartime, engaging with themes of conflict, upheaval and destruction in ways that meld the political and the psychological. This aspect of the Surrealist movement is the theme of “Monsters & Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s,” on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) through May 26.

“There is a generational thing,” says Oliver Shell, associate curator for European art at the BMA, in that “many of these [artists] were young men who fought in the trenches of World War I” and were profoundly affected by the trauma they witnessed and experienced. The development of Surrealism followed on the heels of the Dada movement, which was in part a reaction to the First World War and used dark humor to, in Shell’s words, “express a real contempt for the kind of nationalism that had led to this war and the class of people who had led them into the trenches.” By contrast, Surrealism was more “inward-looking, trying to figure out where the propensity for violence lives within us.”

Enter the Minotaur, which ultimately became a kind of emblem for the Surrealist movement. This is attributable, in part, to the influence of painter and printmaker André Masson and his brother-in-law, the writer Georges Bataille. In considering a name for a new journal of Surrealist art and literature, Masson remembered, “Bataille and I, who were preoccupied with the most somber Greek myths (in particular the Dionysian myths and the Cretan labyrinth), made the case that our era was absolutely ‘Minotaurian,’ and we prevailed.”

By “Minotaurian,” Shell points out in the catalog, they meant that they were living in “an age of monsters.” The journal Minotaure began publishing in 1933, in the lead-up to the Spanish Civil War, and would run through 1939, coming to an end only as war overtook the rest of Europe.

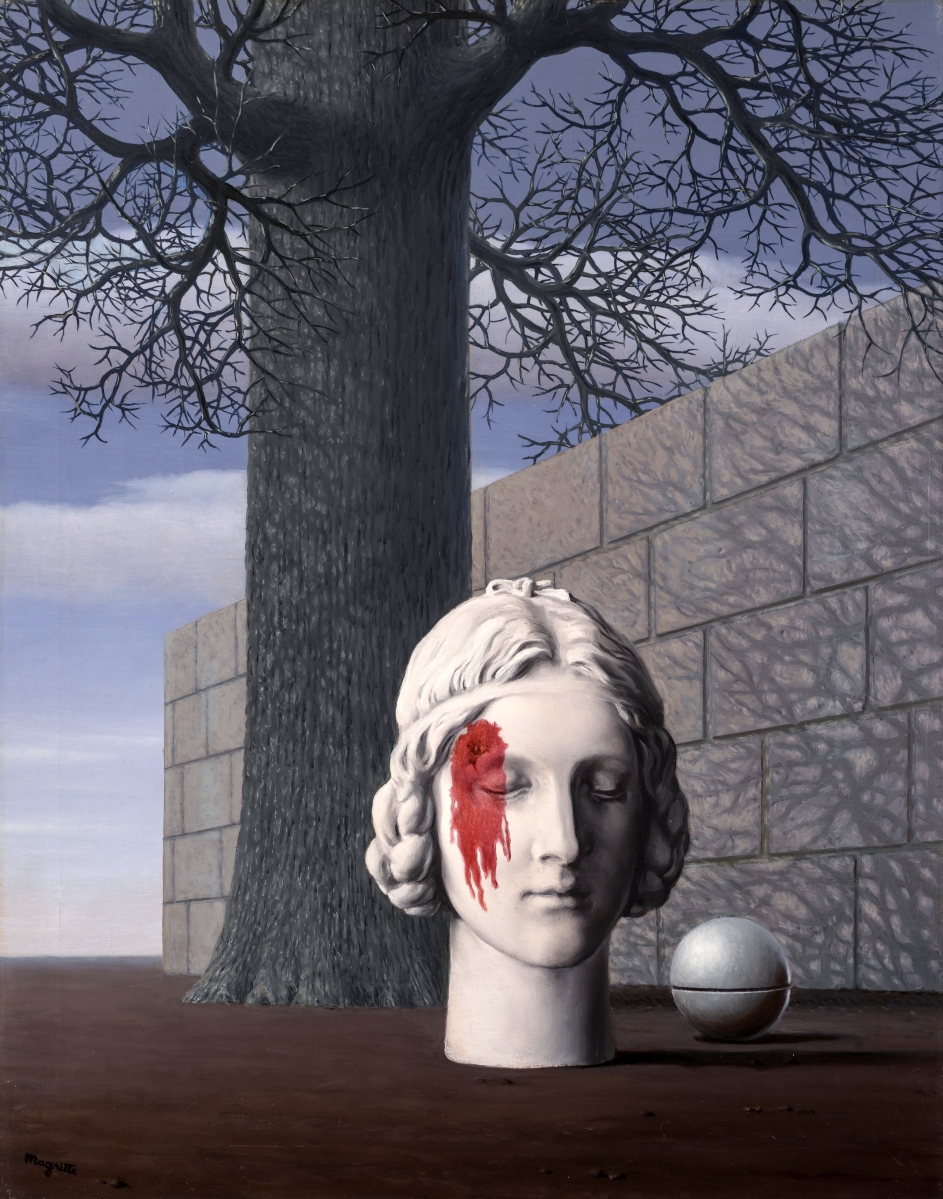

Masson used the Minotaur in many of his works, but the artist who is perhaps most popularly associated with the theme is Pablo Picasso, whose famed etching “Minotauromachy” was completed in 1935, one year before civil war broke out in his native Spain (the title is a portmanteau of “Minotaur” and “tauromachie,” the French word for bullfight). In her essay for the exhibition catalog, scholar Robin Adéle Greeley argues persuasively that the print, which shows the Minotaur hovering menacingly over the fragmented figure of a nude woman and terrified horses, prefigures the composition of “Guernica,” the artist’s famous painting of 1937 that was an impassioned outcry against the bombing of Spanish civilians in a Basque market town.

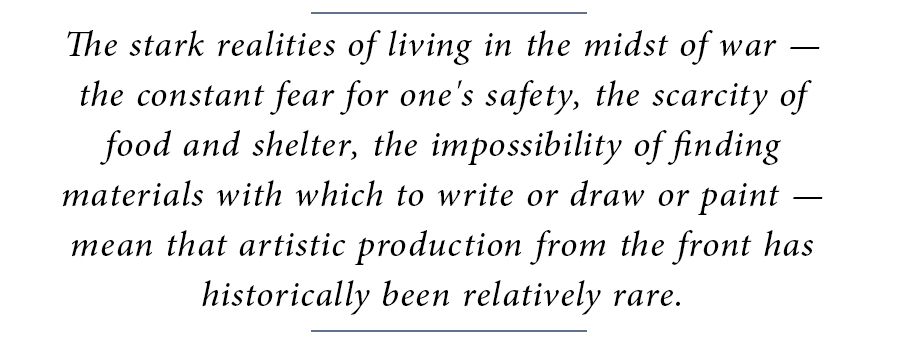

Accordingly, “Minotauromachia” appears in the section of the exhibition that is titled “Premonition of War.” Here, too, is Hans Bellmer’s unsettling “The Doll,” a photograph depicting what appears to be an artist’s manikin overgrown with cancerous tumors, and Max Ernst’s “The Barbarians,” which the artist connected to the “degenerate artist” classification imposed on him (and many others) by the Nazi regime. The identity of the helmeted, beak-nosed, Minotaurian creatures rising up against a blank sky is “ambiguous,” writes scholar Samantha Kavky in the catalog. “Are they the Germanic hordes threatening civilization? Or are they the ‘primitives,’ ‘degenerates,’ and others excised from the Third Reich, rising up in revenge?”

“Premonition of Civil War” is actually the subtitle for Salvador Dalí’s “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans,” although the conflict in Spain had already broken out by the time he completed it. It is painful to look at – contorted body parts stretched across an arid landscape. Shell marvels at how it is “painted with this meticulous detail while being completely constructive of the unconscious”; in other words, it gives the simultaneous effect of hyper-reality and hyper-unreality, a fever dream of a world in which things that should be impossible are happening nevertheless. Dalí himself spoke of the composition as a “vast human body breaking out into monstrous excrescences of arms and legs tearing at one another in a delirium of auto-strangulation” – a description that applies disturbingly well to civil war itself.

The Minotaur had special significance in the country that invented the bullfight, where man and bull square off in a public arena in a fight to the death. The mythical monster combines both beings in a new kind of creature that is perpetually at war with itself – again, a fitting symbol for civil war. But the bullfight itself was also of interest to artists who sought to capture the violence and spectacle of their time. In 1938, André Masson produced illustrations for fellow Surrealist Michel Leiris’ text Le miroir de la tauromachie (The Bullfight as Mirror), which observes how “all the movements are technical or ceremonial preparations for the public death of the hero,…that bestial half-god, the bull.” Masson’s painting “Tauromachie,” produced the year before, seemingly shows an inversion of that trope: the matador is flung over the back of the bull, his eyes closed and his face gray, and the conquering bull, with his wild eyes and flaring nostrils, looks more monster-like – Minotaurian – than godlike.

Masson, who was French, observed the conflict in Spain from some geographical and psychological distance, but his Spanish colleagues felt the brunt of it more directly. Although Picasso, Dalí and Joan Miró all managed to flee to France, they remained actively involved in protesting the fascist regime of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. Divorced, if only temporarily, from their homeland, the incorporated remembered landscapes into their compositions. Dalí’s “Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach” and Miró’s “Summer” share similar imagery in each artist’s inimitable style: a stark shoreline, an inscrutable face, a round and impassive sun. The works’ meanings are ambiguous by design, but undeniable in them is a pervasive sense of distance and disaffection.

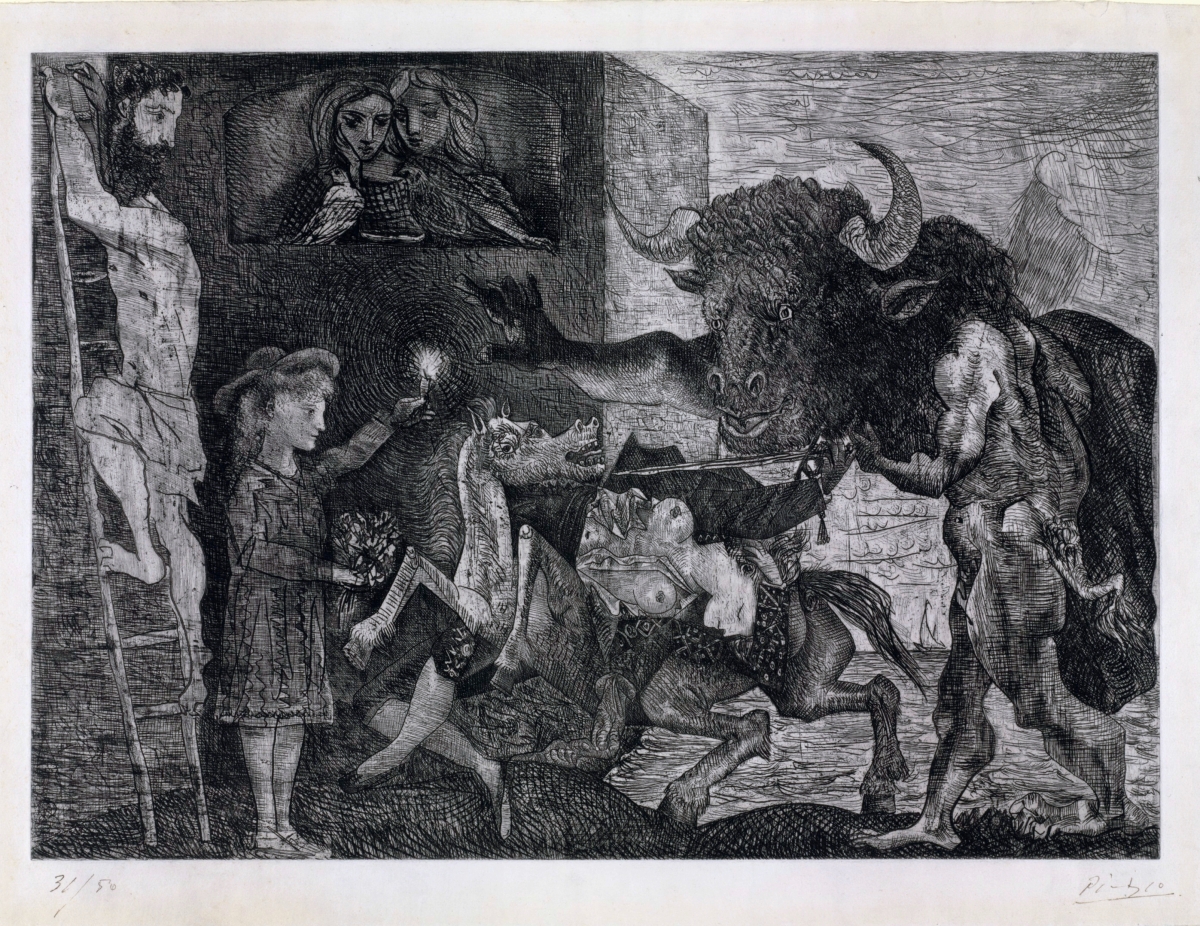

War has often proved to be a catalyst for great and important works of art – “Guernica” serves as a key example. And yet, like “Guernica,” and like the aforementioned works that reference the Spanish Civil War, such works are generally produced with the benefit of distance, either geographical or temporal. The stark realities of living in the midst of war – the constant fear for one’s safety, the scarcity of food and shelter, the impossibility of finding materials with which to write or draw or paint – mean that artistic production from the front has historically been relatively rare. Baltimore’s exhibition, though, includes at least two works that are exceptions.

“Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War)” by Salvador Dalí, 1936. Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950 ©Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society.

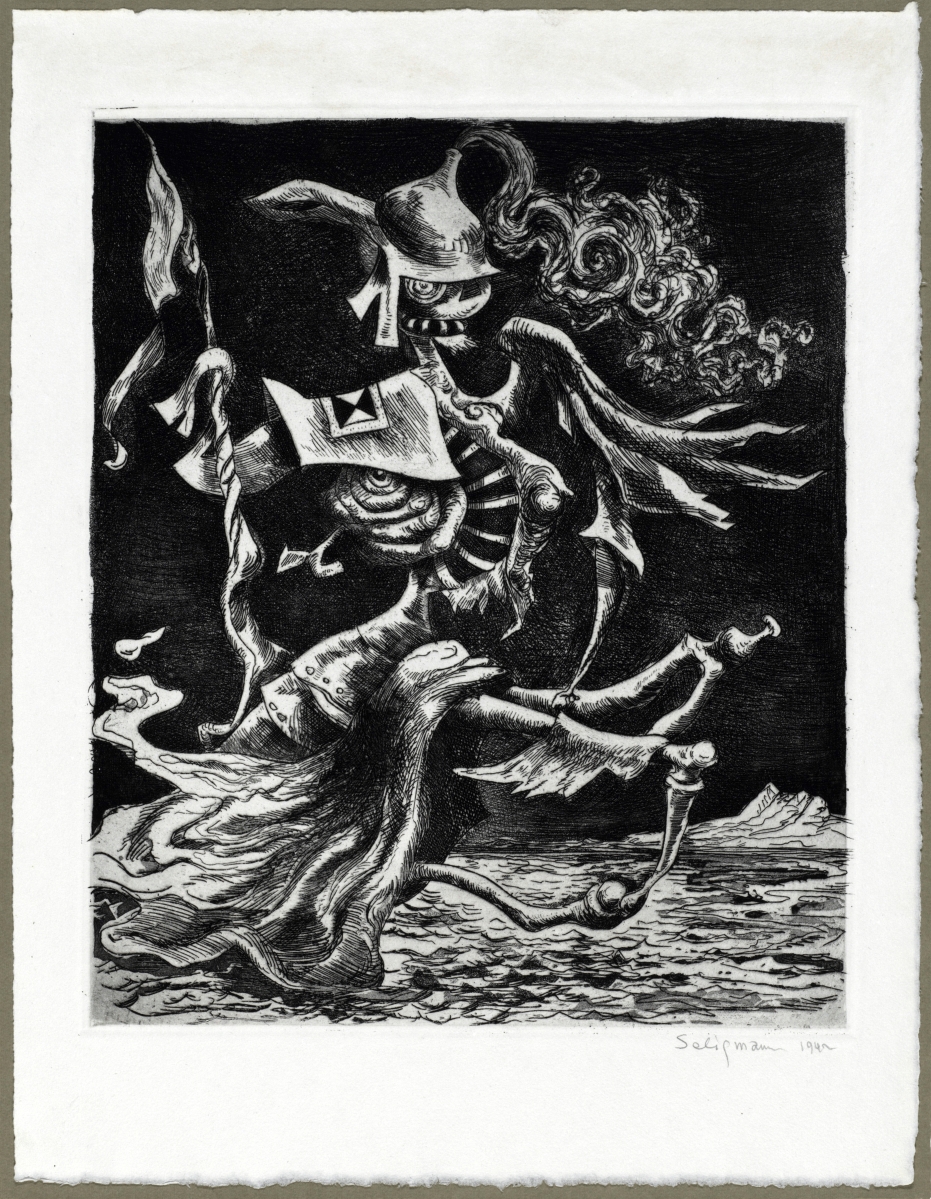

One is André Masson’s “The Metaphysical Wall” of 1940, which, impossibly, was produced even as Germany was invading France. The work’s complex imagery – an entombed skeleton next to a child in the womb, a seemingly impassive wall that nevertheless appears fragile and vaguely transparent, tall male and female figures that are either protecting or threatening – capture the untenableness of Masson’s position in occupied Paris. His wife was Jewish, which meant that they had to flee, or the entire family could be sent to a death camp. In the end, an American patron, Saidie Adler May of Baltimore, helped them to escape to America. Masson gave this painting to May after the war was over, and she in turn bequeathed it to the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Another wartime work is “Europe After the Rain II” by Max Ernst. A native German branded as a dissident and a “degenerate” artist, Ernst was exiled from his home country and became a semi-prisoner, semi-refugee in France. After the German invasion, though, he was arrested by the Gestapo and only managed to escape with the help of the art dealer Peggy Guggenheim, whom he later married. As Oliver Tostmann, curator of the Wadsworth Atheneum (which co-organized “Monsters & Myths”) writes in the exhibition catalog, Ernst had begun “Europe After the Rain II” in Europe. As he prepared to flee, he “shipped the unfinished canvas from southern France to “Max Ernst, c/o Museum of Modern Art, New York.” Miraculously, it reached its destination intact shortly after Ernst’s own arrival in the United States, in July 1941.” Shell spoke about how the work was later completed in America in 1942, inspired in part by a cross-country trip that Ernst and Guggenheim made shortly after their wedding. “[There is a] European side, with a bull and a nude female, but the left-hand side is all just a rocky landscape that looks like Sedona [Arizona],” Shell notes. “It followed his migration and assimilated influences from the American West.”

“Surrealism in the Americas” is the title of the concluding section of the show, and a centerpiece here is Masson’s “There is No Finished World,” also a bequest from Saidie May to the BMA. Rare for the Surrealist genre, this work has a written key, direct from the artist, that explains its complex imagery: the Greek gods Pan, at left, and Demeter, center, along with the Minotaur at the right. “We are thinking it was at Saidie May’s suggestion” that he created this key, says Shell. Such allusions would have been familiar to “anyone who’d gone through a European education system,” but May would have had American audiences in mind – probably the specific audience of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

One of the more surprising works in this section from the show is an early painting by Mark Rothko, better known for his abstract color field paintings of the 1950s. But Rothko began his career as an ardent Surrealist in America, and his “Syrian Bull” resonates not only with the Minotaurian imagery of Masson, Picasso and others, but also the compositional and coloristic innovations of Miró. Shell argues that Surrealism was influential for many of the artists that we now see as the pioneers of the New York School. “[There are] masterpieces of Abstract Expressionism that show how early on these American artists were quite fascinated by these major European artists in their midst… [They were] picking up on mythological themes but also automatic techniques.” By “automatic,” Shell refers to art-making techniques that rely on chance, many of which were developed by the Surrealists.

“Fumage,” for instance, was a method of holding a burning candle against a painted surface to create a flickering shadow effect. “Decalcomania,” used by Ernst to create the craggy landscape forms in “Europe After the Rain II,” involved pressing splotches of pigment against the canvas with a flat surface to create a random shape. It’s not too far a journey from there to the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock, who after all first broke onto the scene with a major canvas titled “Pasiphaë” – the mother of the Minotaur.

This, in the end, is one of the great contributions of the exhibition and catalog: they knit together interwar, prewar and postwar phenomena that have so often been seen as discrete and contradictory – as being irreparably rent apart by the decade of war in Europe. By bridging that seemingly impassible historic moment and by showing what emerged from it, “Monsters & Myths,” despite its challenging imagery, ultimately affirms the theme of rebirth and redemption that is an undercurrent of even the darkest myths.

The Baltimore Museum of Art is at 10 Art Museum Drive. For information, www.artbma.org or 443-573-1700.