Charles Henry Miller (1842-1922) studied painting at the Royal Academy in Munich. When he returned to America, he settled in Queens, N.Y., and by 1874, his subject matter focused primarily on picturesque Long Island scenes. “The Rising Moon” by Charles Henry Miller, circa 1880. Oil on canvas.

By Rick Russack

HUNTINGTON, N.Y. – Images and myths concerning the moon exist in nearly every culture on our planet. NASA considers the earliest known representations of the moon to be lunar calendars on cave art found in France and Germany, with roots going back more than 30,000 years. Other sources state the age of lunar representations in cave art on the walls of caves in Lascaux, France, to be 15,000 years old. Many countries and cultures lay claim to the “earliest” representations of the moon. Obviously, interest in the moon is not a recent phenomenon. Leonardo da Vinci depicted the moon in the early years of the Sixteenth Century, but probably the first depiction in western art was about a hundred years earlier, done by Jan van Eyck whose first painting including the moon was done in 1420.

“Moonstruck: Lunar Art from the Collection” is an exhibit of more than 30 images of the moon on view at the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, on New York’s Long Island, running from January 20 through September 18. It includes lithographs, oil paintings, watercolors, photographs and sculptures, as well as serigraphs, linoleum block prints, ballpoint ink drawings and a digital dye-sublimation print on aluminum. The works were created over a time period of more than 150 years between 1870 and 2021. “Moonstruck” is organized by Karli Wurzelbacher, curator, the Heckscher Museum of Art; and Shelley DeMaria, art historian and curator.

The exhibition will fill two galleries and highlight paintings from the founding collections, which had belonged to August and Anna Atkins Heckscher, who funded the museum’s construction in 1920. Objects from recent acquisitions will also be included.

“Moon Dreamers” by Joseph Hirsch, circa 1962. Ballpoint ink on paper. Gift of Dr and Mrs Marvin Sinkoff.

According to curator Karli Wurzelbacher, works by Nineteenth Century European and American artists, displayed in the first gallery, “gravitated to the moon as subject matter in response to rapid modernization and urbanization. The shining orbs in their nocturnal landscapes are emblems of the power of nature and also nostalgic reminders of a world before the Industrial Revolution and electric light.” A second gallery, Wurzelbacher continued, “explores how our understanding and thoughts about the moon changed again during the Space Age, as science fiction morphed into reality. With NASA’s 1969 lunar landing, the moon became tangible, but no less captivating. This gallery explores understandings of the moon as cosmic, surreal and mythic.”

One of the highlights in the exhibition is “The Poetry of Moonlight” by Ralph Albert Blakelock (1880-90), an oil on canvas. It depicts the full moon rising behind and above trees in the foreground. It was part of the original Heckscher collection and the artist apparently was a favorite of Heckscher, as the museum’s collection includes five of his works, more than any other artist. Blakelock was primarily a self-taught artist whose works became quite popular in the early years of the Twentieth Century, with forgeries appearing as early as 1903. One of his paintings, a moonlight scene, sold for $20,000 in 1916 – at that time the highest price achieved by a living artist.

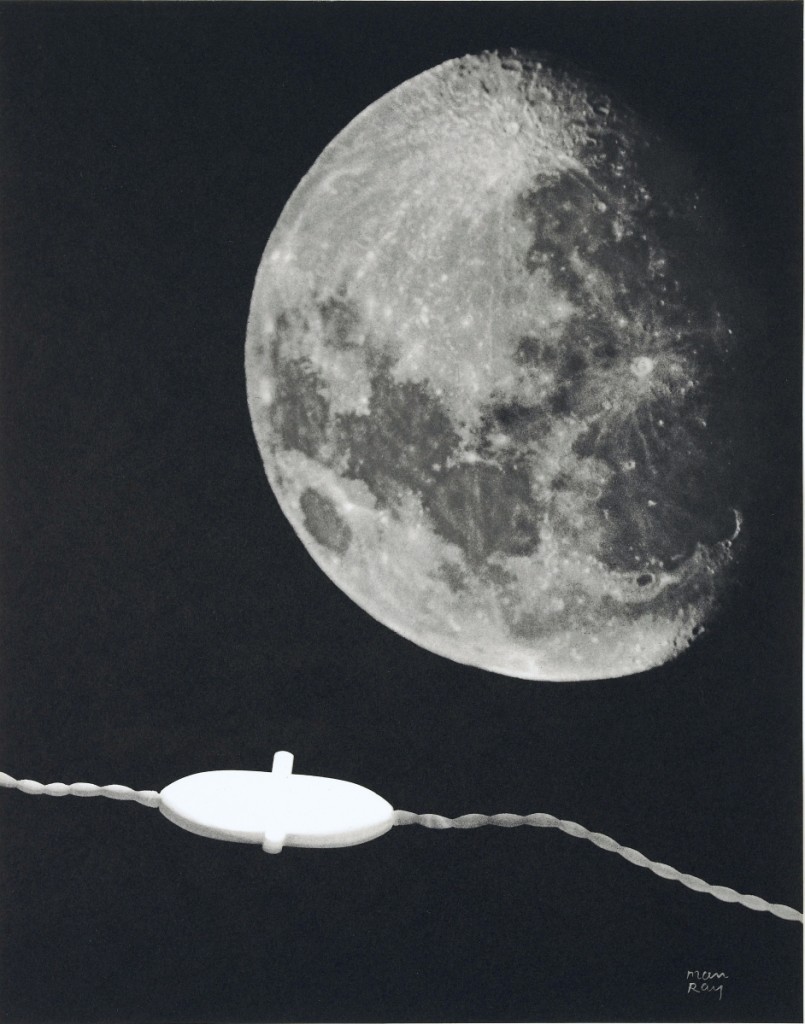

Another highlight, although certainly at the opposite end of the spectrum, is the newly acquired “The Moon Person Ascends” by at Jeremy Dennis, (b 1990) a contemporary fine art photographer, winner of several awards and a tribal member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation in Southampton, N.Y. This work gives visual form to a Native American story, attributed to the Biloxi Nation, a Louisiana tribe, that accounts for the moon’s crater and phases. Dennis relates this historic myth through the relatively new medium of digital photography. Photographic images of the moon date back to the earliest days of the medium, with one having been done by Louis Daguerre in 1839. That one was destroyed by a studio fire and the earliest surviving photograph of the moon is believed to be a daguerreotype done by John Draper in 1840 and now owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition includes photographs by Man Ray and Edward Steichen.

“Le Monde” is one of ten images in the portfolio “Electricite,” commissioned from Man Ray (1890-1976) in 1931 by a French electric company to promote the domestic uses of electricity. In 1917, he invented, by chance, rayographs, which were produced by placing various objects on light-sensitive paper in the darkroom and exposing the paper to light, creating images that resemble x-rays. “Le Monde (The World)” by Man Ray, 1931.

Another monumental highlight is “Coin Noir” by James Rosenquist (1933-2017). A proponent of the Pop Art movement, Rosenquist pushed the traditional boundaries of printmaking. At a time when most artists were producing modestly sized black and white prints, Rosenquist created vibrantly colored works that rivaled the scale of paintings. “Coin Noir,” translated as “Black Corner,” evokes the starry night sky and incorporates imagery that suggests science and technology, reflecting Rosenquist’s fascination with outer space, technological advances and scientific theory.

We discussed the exhibition with Wurzelbacher. “I wanted to do this exhibition because our founding collections include numerous works with images of the moon. When I noticed that, it just seemed appropriate that we highlight those works along with related works that we have. The moon affects so many aspects of daily life that we sometimes overlook. It affects the tides, many cultures schedule planting times by the phases of the moon and it’s always been a source of wonder – what’s up there? What is it? Artists have always used changing technologies to capture images, from cave drawings to digital photography. The moon landings encouraged more curiosity, so it’s a rich source of inspiration. It’s time to let folks know about our collections and maybe encourage them to think about how perceptions and concepts of the moon have changed. Artists have portrayed the moon in endless ways: romantically, nostalgic, natural scientific, surreal, dreamlike, spiritual, and that list could go on and on. The artworks in ‘Moonstruck’ reveal the intersections of romanticism and technology, mystery and discovery, imagination and fact. Now with the advent of “space tourism” and NASA’s plans for the next moon landing as early as 2025, these images reflect the perpetual pull of the moon.”

Wurzelbacher has been with the museum since 1999. She previously was assistant curator at the Hunter College Museum of Art and earned her PhD at the University of Delaware.

For more information about this exhibit, or the museum, visit www.heckscher.org or call 631-380-3230.