The second gallery displays pamphlets on loan from the Crab Tree Farm Foundation. Installation image of “Morris & Company: The Business Of Beauty” at the Art Institute of Chicago through June 13. Photo Joe Tallarico.

By Karla Klein Albertson

CHICAGO – “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.”

If everyone followed those words of William Morris (1834-1896) in his 1880 discussion of The Beauty of Life, the world – at least, that part where we spend much of our time – would be a better place. “Morris and Company,” an exhibition at The Art Institute of Chicago through June 13, explores how his foundation of a firm devoted to the creation of beauty attempted to eliminate the curse of repellant surroundings.

Morris was a man of many passionate enthusiasms in both related and far-flung fields. He was an aesthete and an antiquarian, fascinated by the culture of the Medieval Period. Artistic contemporaries that he counted as friends included Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, notable members of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. In addition to a devotion to creating the beautiful, he also had socialist political viewpoints that influenced his actions.

So strong has been the focus on his talent for design that many have forgotten that he was also an author of poetry, essays and fiction and the translator of ancient and medieval texts. In the 1890s, he was writing books like The Well at the World’s End, which puts him into the alliterative fantasy-fiction-founder category. The much younger J.R.R. Tolkien, eventually more famous in the field, had been a reader of Morris’ works with their underlying Icelandic influence.

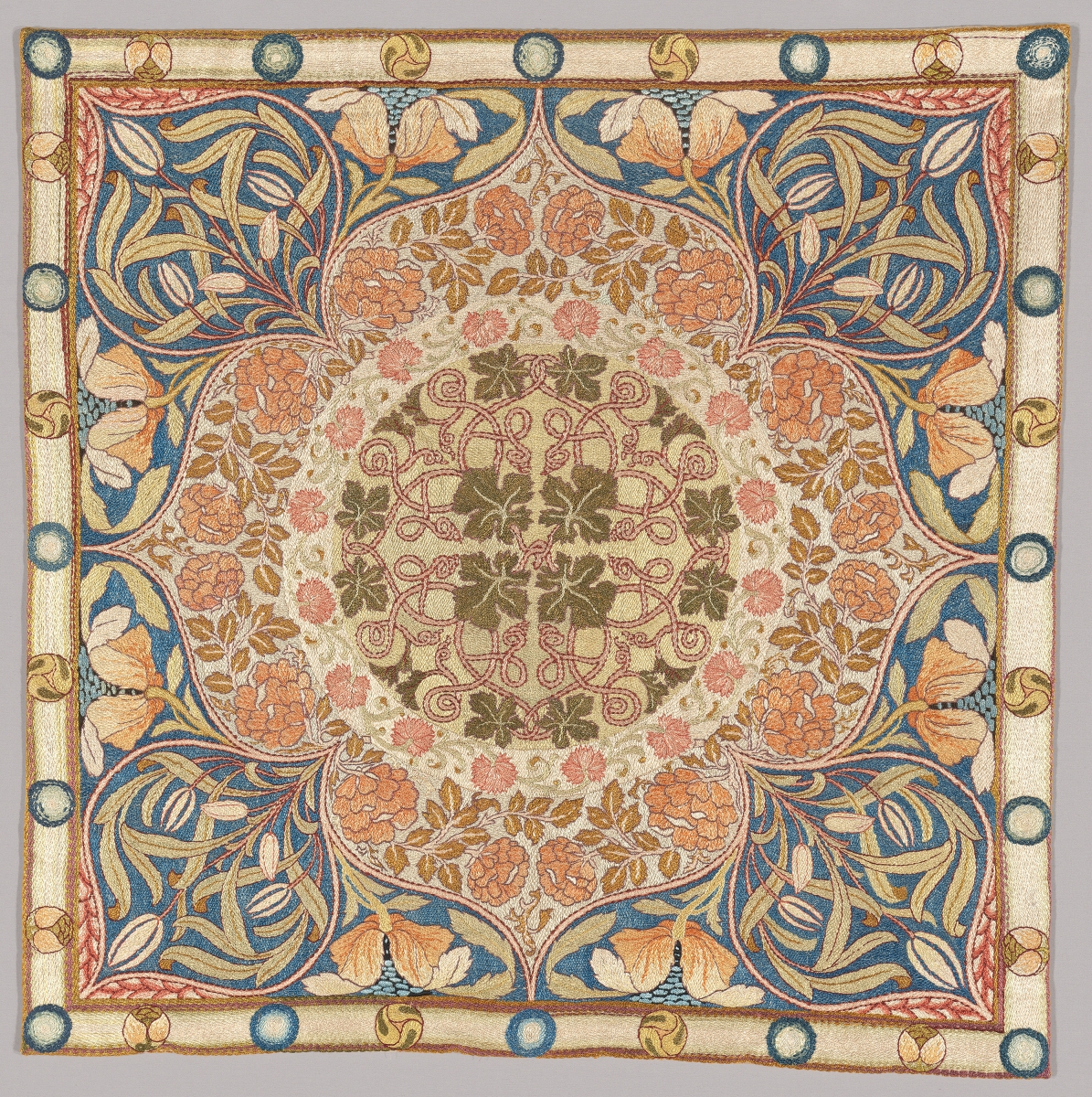

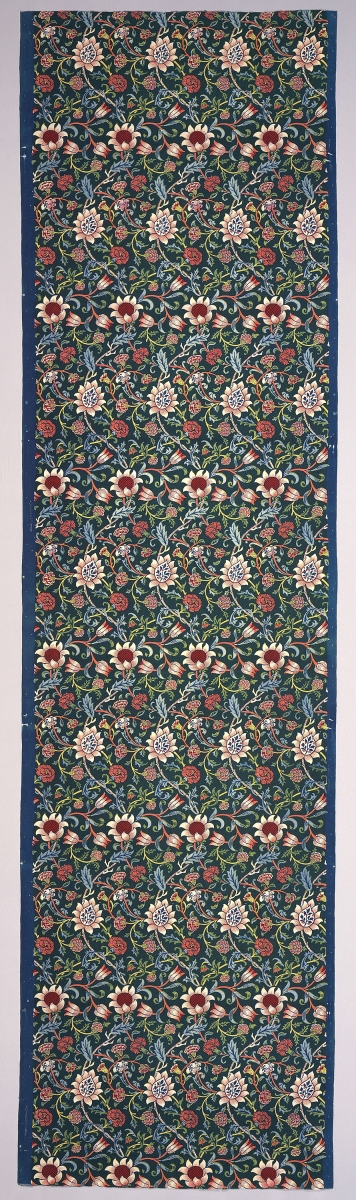

But the Chicago exhibition – as indicated by the title – focuses on the foundation and philosophy of Morris & Co., founded in 1861, with the collaboration of William’s wife Jane, an excellent embroiderer, his artistic daughter May, and creative friends such as Burne-Jones and Rossetti. The exhibits are predominantly textiles and wallpapers with lush designs drawn from the natural world.

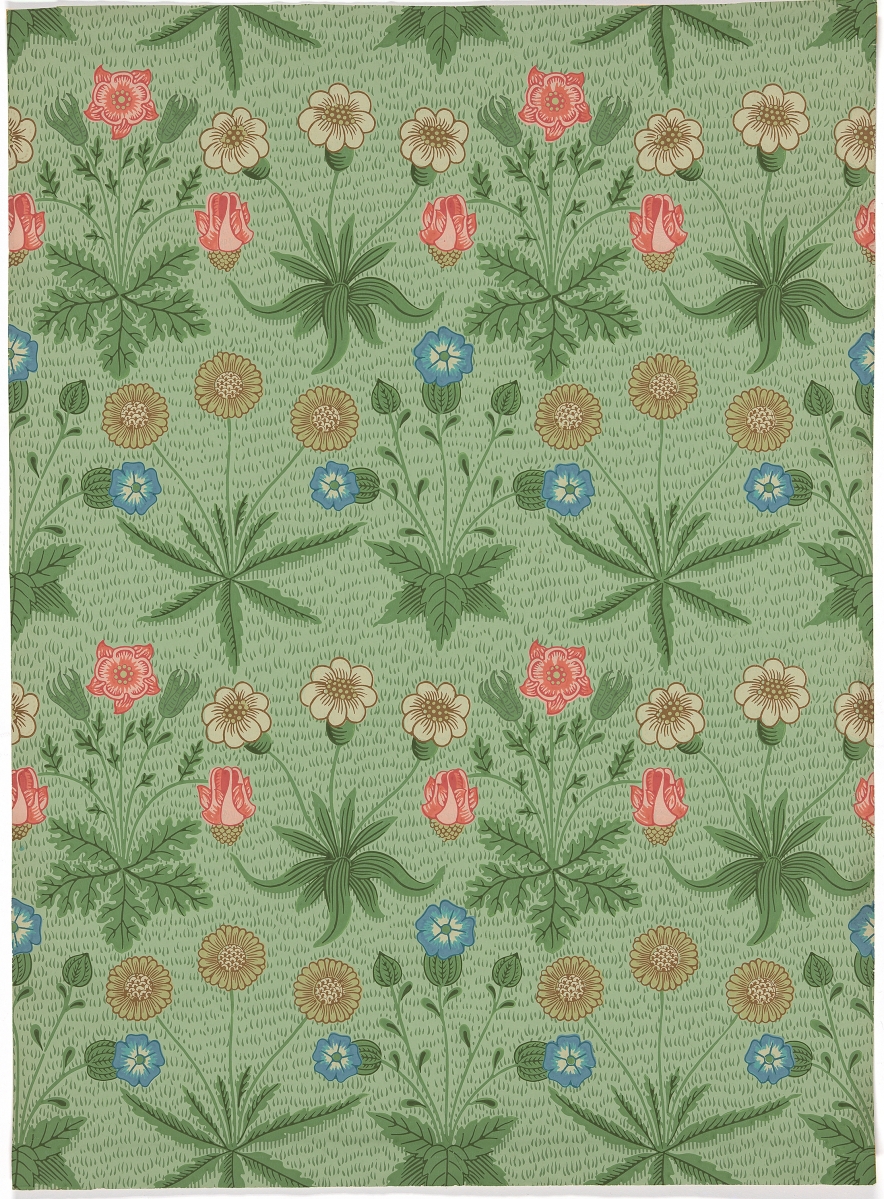

“Pimpernel,” design 1876. Designed by William Morris (English, 1834-1896), produced by Morris & Co., London (English, 1875-1940), printed at Jeffrey & Co., London (English, 1836-1927). Woodblock print in colored inks on cream wove paper, 22½ by 29- inches. Gift of Crab Tree Farm Foundation.

Entering the pattern-saturated gallery, visitors are introduced to the company philosophy: “Designing and making objects primarily for home interiors, the enterprise strove to fuse art and life, and the Morris style quickly became synonymous with the British Arts and Crafts movement of the late Nineteenth Century. Morris and collaborators espoused a philosophy that exalted handmade objects over mass-produced goods. Their lofty goals were to foster an appreciation for the design and handmade production of household furnishings and to bring beauty to the lives of all citizens.” A lofty goal, indeed.

The organizing spirit behind this important exhibition is Melinda Watt, chair and Christa C. Mayer Thurman curator of the Textiles Department, who came to the Art Institute four years ago from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where she had been working in the department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts and was responsible for Western European textiles.

Talking about the origins of the show with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, she explained that the theme was a natural choice because of the contributions made by local civic leader and museum supporter John H. Bryan, Jr, who passed away in 2018. He had been an avid collector of British decorative arts – read more about his work at the Crab Tree Farm Foundation website. The curator explained that his generosity “put us in a stellar position to take a comprehensive look at the textile and wallpaper designs of Morris & Co.”

“When he gave us this gift in late 2018, I thought, we can present a comprehensive view of design strategies but also think about the longevity of the Morris & Co. aesthetic, and we can do it with our permanent collection. There have been a number of Morris exhibitions in England and in northern Europe and important Pre-Raphaelite exhibitions here in the United States. But Morris & Co., William Morris himself, May Morris, his daughter – who became such an important designer and also ran the embroidery studio – I don’t think they really have gotten their due in the United States.”

Watt also wanted to introduce a local audience to the material because of an important Chicago connection. A house still standing in the Prairie District, designed by Henry Hobson Richardson for John and Frances Glessner and completed in 1887, had been furnished with Morris textiles and wallpapers. The website features views of the architecture and collections.

The Glessner family in Chicago purchased a richly patterned Morris & Co. carpet for their front hall, where it appears in the foreground of a photograph made around 1923. The knotted pile example of wool and cotton is now in the collection of the Art Institute.

As far as the designer’s sources of inspiration were concerned, the curator stated: “Morris was very knowledgeable about historical textiles – he had his own collection, he consulted with the Victoria & Albert Museum, he advised them on purchases, he studied their historical collection. He was very well-versed in pattern design of the late Middle Ages through the Eighteenth Century, and we see echoes of that in all of his work. He really understands repeating pattern design at a very deep level. But he’s also insisting on revisiting, revising, reinventing historical techniques. He learned how to use natural dyes and how to weave tapestry and to weave on a floor loom, how to embroider. He was a very well-educated man, but in terms of process, he doesn’t hesitate to get his hands dirty.”

Finding the best way to display pattern pieces was met by creative exhibition design: “I worked with two young designers – the exhibition designer Samantha Grassi and the graphic designer Marc Choi. I’m finding with younger audiences that they really respond to this maximalist aesthetic. And they respond to the diversity of his activities – that he didn’t settle for just being a designer of repeating textiles or one type of textile technique. But he was the type of person that was constantly questioning and exploring and creating in many ways. Samantha Grassi responded to my idea of having wallpaper throughout the exhibition. Marc Choi really embraced the idea of him being a highly literary person, he used graphics that look somewhat book-like.” Watt found it to be a gratifying collaboration and emphasized their thoughtful design.

The curator concluded, “I am not attempting to show Morris’ work in its entirety – this is about the textiles and wallpapers. They were and are the bread and butter of his company. I want visitors to realize the continuing relevance of Morris & Co. designs. People who are familiar with this work revel in seeing a quantity of this work in one place. People who are not familiar, I hope that they start to understand that this still feels relevant.”

“I’m also extremely pleased to bring the May Morris story to the fore. We have one gallery that is devoted to embroidery and to her work.” To read more about the daughter in the family business, go to the artic.edu website under “articles” for Watt’s discussion of “May Morris: Designer and Advocate.” There the curator notes, “May harshly criticized the economic structures that resulted in low prices for handmade embroidery – prices that reflected neither the aesthetic value of the work nor the value of the labor involved.” An American lecture tour May undertook in 1909-10 spread an interest in Morris & Co. designs as well as her strong personal viewpoints.

“Pomona,” figure design 1882, background design 1898, made 1906. After designs by Sir Edward Burne-Jones (English, 1833-1898) and John Henry Dearle (English, 1860-1932), produced by Morris & Co., London (English, 1875-1940), woven by Walter Taylor (English, 1875-1965) and John Keich (English, active 1890s-1910), Merton Abbey Tapestry Works, London (English, 1881-1940). Cotton, wool, and silk, slit and double interlocking tapestry weave, 36½ by 65 inches. Ida E.S. Noyes Fund.

To gain a deeper understanding of the multi-faceted head of the family, the curator recommends the new volume William Morris, edited by Anna Mason, released last November by the Victoria & Albert through Thames & Hudson, on the 125th anniversary of the artist’s death.

Many other scholars have written about Morris’ determination to do more than just philosophize. Over 20 years ago, Charles Newton wrote a chapter on “William Morris and his Circle” in the Victoria and Albert Museum publication Victorian Designs for the Home. There he said: “Morris was a dreamer but a practical one, in the sense that he was not content merely to imagine but needed to make.”

In a further statement on Morris’ complexity, the author noted: “It is a great irony, and one of the many paradoxes of the Nineteenth Century, that this man did so much to recreate the best bits of the Middle Ages and was influenced by Pugin, the fanatical Christian medievalist, yet he was finally heralded as a pioneer of modernism… Morris’ stern rejection of the gross commercialism of his own age and his practical attempts to restore some kind of integrity in the arts made him a hero for design reformers in the Twentieth Century.”

For those fortunate enough to visit Scotland this year, catch an exhibition on “The Art of Wallpaper – Morris & Co.” at Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh through June 11.

The Art Institute of Chicago is at 111 South Michigan Ave. For information, www.artic.edu or 312-443-3600.