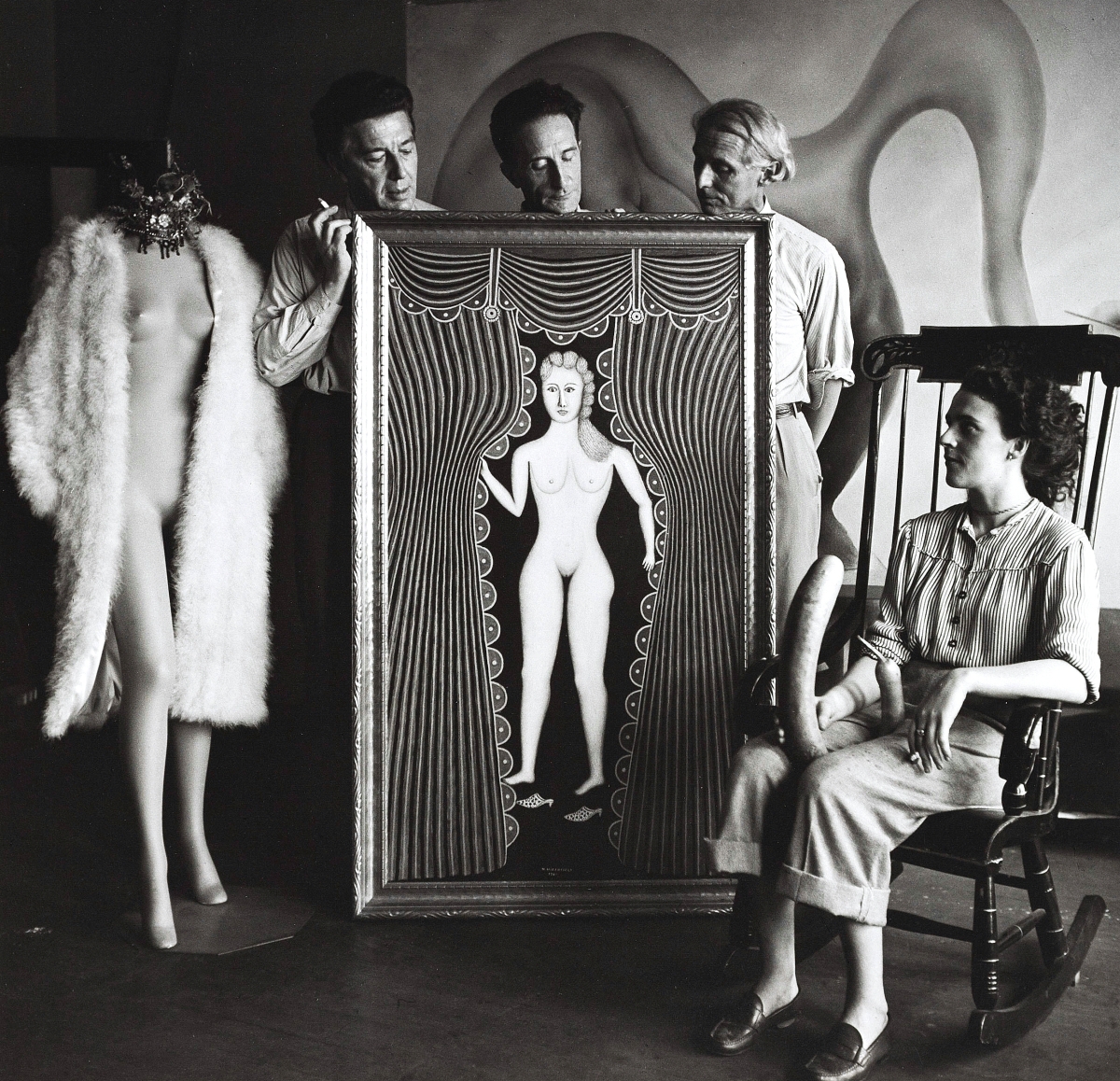

“Tiger” by Morris Hirshfield, 1940, oil on canvas, 28 by 39-7/8 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund, 1941, 328.1941. ©2022 Robert and Gail Rentzer for Estate of Morris Hirshfield / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

NEW YORK CITY – In the study of art history, there is a kind of accepted trajectory for a self-taught artist: years of puttering about within a limited social, economic and cultural sphere before sudden “discovery” and exposure thanks to an art world insider. One might be forgiven for thinking that the painter Morris Hirshfield (1872-1946), active for only about ten years preceding his death in 1946, fits that mold – it is certainly how his story was presented to the art-going public. But the facts tell a tale that this is somehow both more and less typical. Hirshfield, like so many denizens of early Twentieth Century New York City, just wanted to be an artist, and throughout his varied career he never lost sight of that goal. His paintings and the specific path he took to produce and share them are the subjects of “Morris Hirshfield Rediscovered,” at the American Folk Art Museum through January 29, 2023.

The exhibition is guest curated by Richard Meyer, who teaches art history at Stanford University and has just finished a book on Hirshfield: Master of the Two Left Feet: Morris Hirshfield Rediscovered, which serves as the publication for the exhibition. The quirky title comes from a criticism levied at Hirshfield on the occasion of his ill-fated solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1943. Alluding to the art-historical convention of identifying medieval painters by their works – Master of St Cecilia, etc. – a writer for Art Digest dubbed Hirshfield the “Master of the Two Left Feet,” because the figures in his paintings tend to have feet that both point in that same direction. The book and exhibition, Meyer says, seek to “reclaim” the moniker. “If Hirshfield was ‘Master of the Two Left Feet,'” Meyer writes, “it was not because he made pictorial errors but rather because he embraced and exaggerated those errors until they became a sign of his unique vision as a painter.”

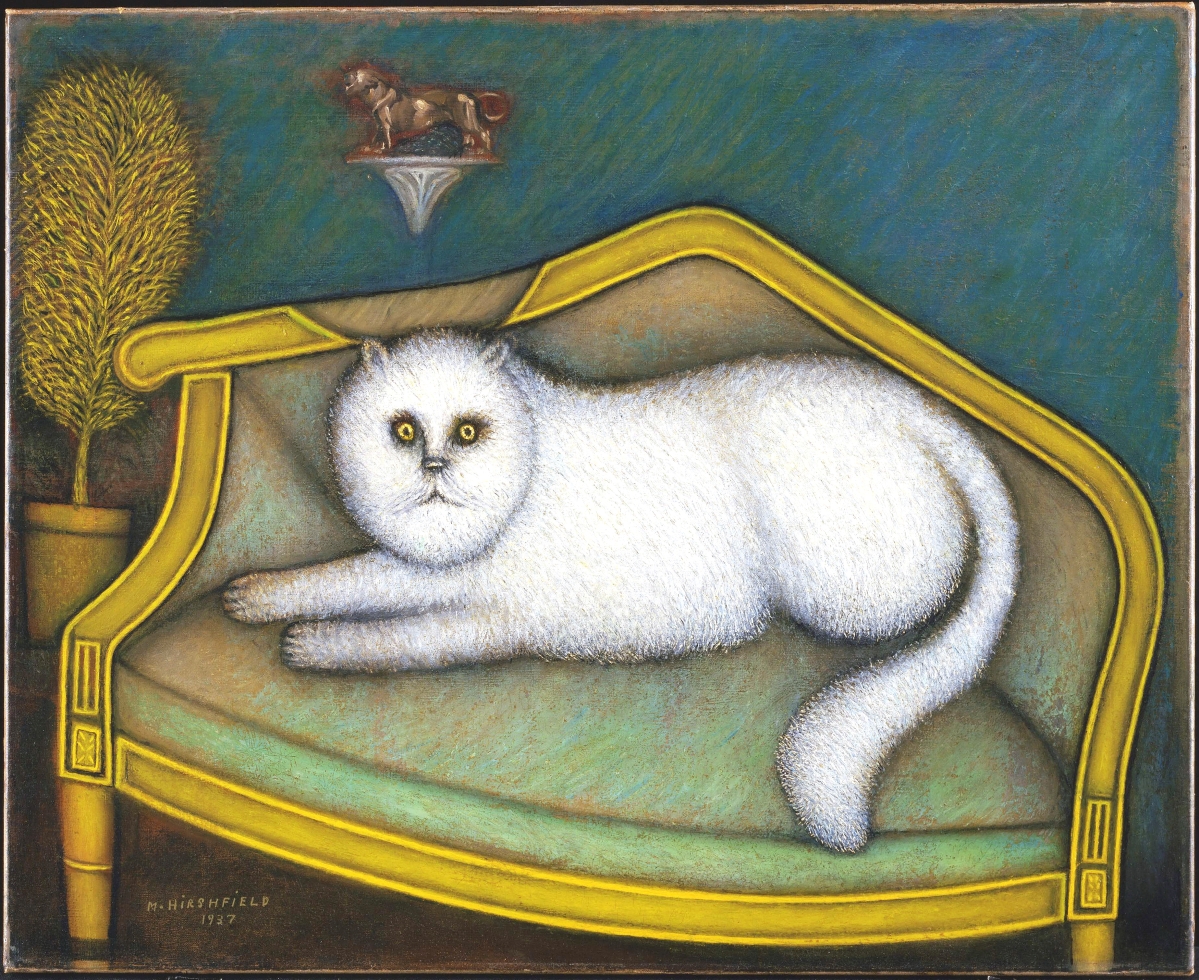

The Art Digest writer was not alone in having difficulty both with Hirshfield’s work and with its display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The exhibition was presented under the directorship of Alfred Barr with support and encouragement from Sidney Janis, an increasingly prominent dealer/collector and a champion of Hirshfield’s work. It wasn’t the first time Hirshfield had been shown at MoMA, which at that point in its history featured – and collected – the work of self-taught artists fairly regularly. But it was his first solo museum show and one of the first and only times MoMA had given a self-taught artist that honor. As Meyer amply demonstrates in his book, there was backlash. There was a certain amount of pearl-clutching over works like “Nude in the Window,” as if museum-going New Yorkers had never seen a painted nude before, but the strongest criticism was directed more at the museum itself than the artist. “While serious, professional artists fight for the recognition that means life to them,” one critic wrote, “the Modern fiddles away its resources building a precious cult around amateurism.” Others lamented that the museum had seemingly made a joke of the artist, whom they perceived as a “fumbling old man who hasn’t an idea why they like him,” and of the public itself, in foisting his work upon them.

Part of the problem was surely the original press release for the exhibition, headlined “Retrospective Exhibition of Primitive Paintings by Retired Cloak and Suit and Slipper Manufacturer Shown at Museum of Modern Art.” While the words are not inaccurate, they are somewhat flattening, suggesting that the most notable thing about the paintings was Hirshfield’s start as something other than a gallery-and-museum artist. When Hirshfield first appeared on the fine art scene, critics had indeed tried to make something of this, relentlessly exoticizing the artist for having immigrated from Russian Poland, for being Jewish, for speaking with an accent, for living in Brooklyn, for working in the garment industry, etc. But by the time of the MoMA show, it was almost as if there was a collective agreement that his backstory was not so very exotic after all – which is true – and an attendant consensus that his art therefore wasn’t particularly noteworthy either, which is not true. It was Hirshfield’s misfortune – and ultimately Barr’s too, as he was fired not long after the show – that a public either not ready or not adequately prepared for his work was most comfortable dismissing it as the idle work of a retired suburban hobbyist.

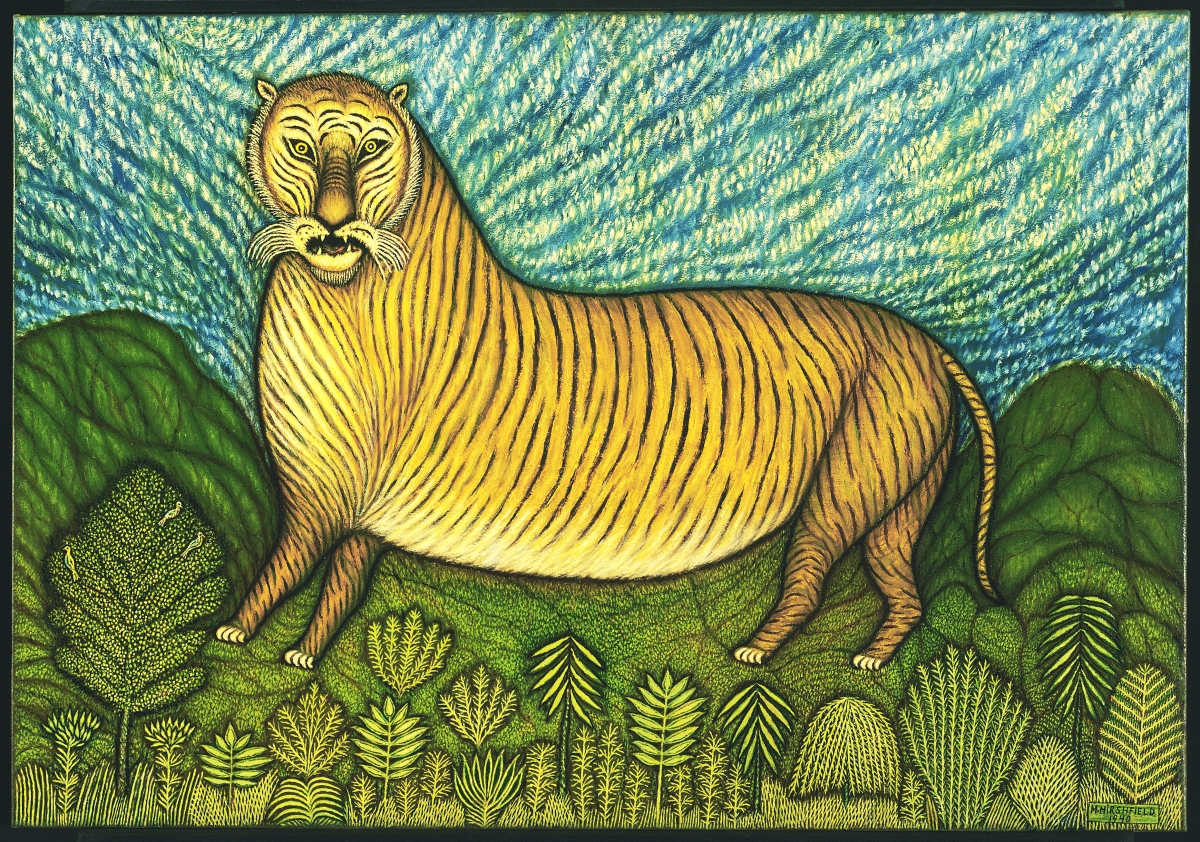

“Parliamentary Buildings” by Morris Hirshfield, 1946, oil on canvas, 36-1/8 by 28 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection, 1969, 611.1967. ©2022 Robert and Gail Rentzer for Estate of Morris Hirshfield / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

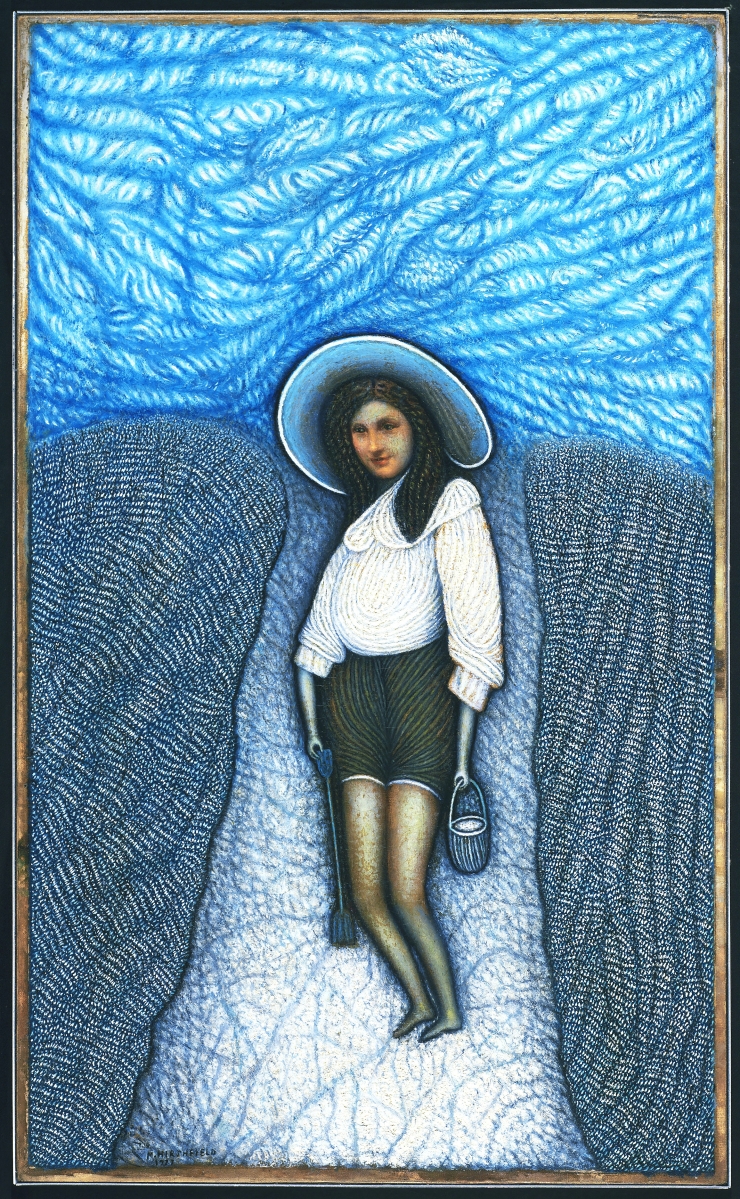

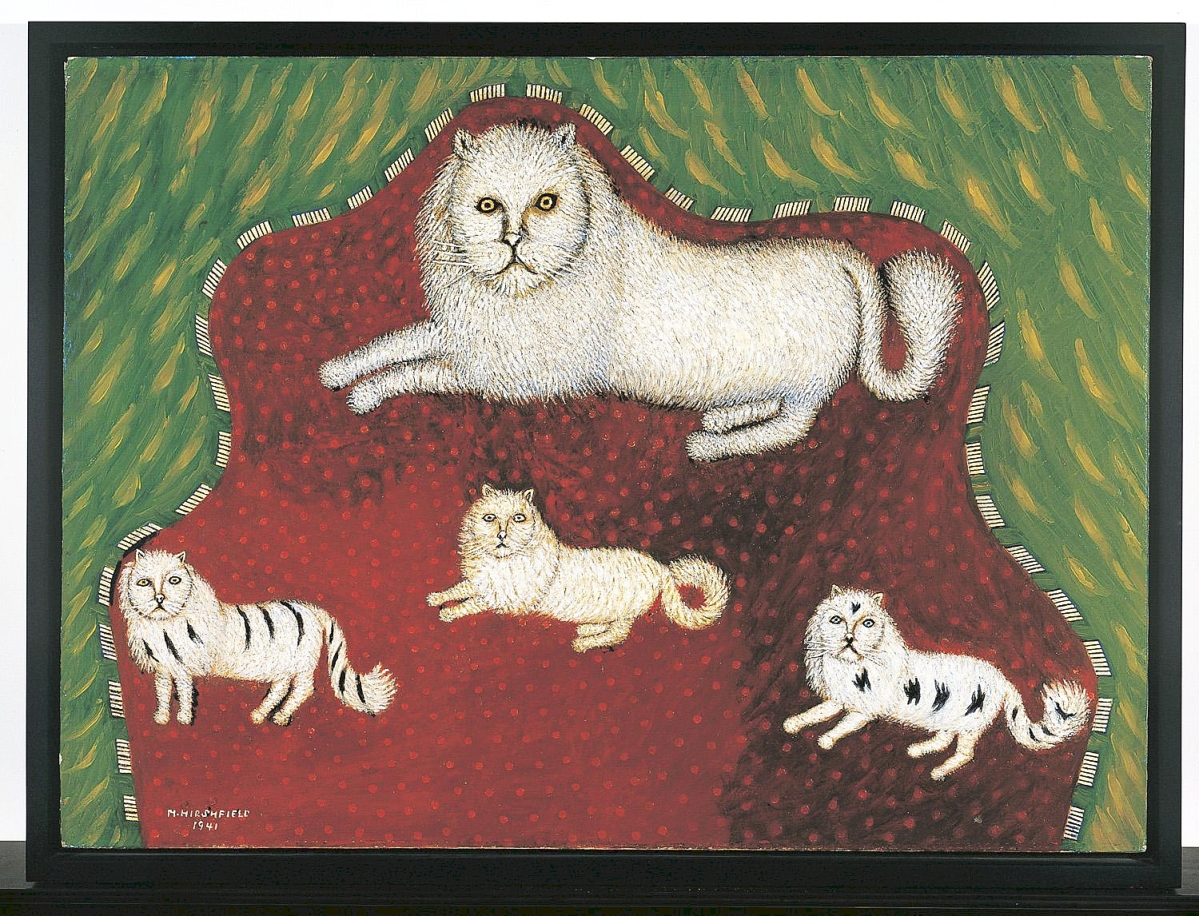

The irony to all this is that Hirshfield was never a hobbyist; he was, in fact, a “serious, professional artist” and never an amateur. Upon arriving in the United States at the age of 18, he found a job as a pattern cutter and quickly parlayed that skill into building his own business as a tailor and, later, the proprietor of a woman’s clothing shop, where he and his brother Abraham designed and made all the garments. Meyer talks about a kind of rootedness in textiles that stayed with Hirshfield through the production of his paintings in the 1930s: the yarn-like skies of “Beach Girl” and “Tiger;” the flecked patterns of “Mother Cat with Kittens.” Though the business operated for 12 years, and Hirshfield remembered that although “we were creating a very nice line of merchandise,” the brothers sought to turn a larger profit, and they found that opportunity in footwear. The E-Z Walk company that they founded featured proprietary arch supports and ankle straighteners – the patents show evidence of Hirshfield’s careful, professional draftsmanship – and ultimately a line of “boudoir slippers” that made him a millionaire.

The roaring success of E-Z Walk’s slipper line and Hirshfield’s ensuing role as a captain of New York’s garment industry make the critics’ persistence in seeing him as a simple-minded old man seem absurd enough. However, the sheer exuberance of the slippers and the obvious delight that went into their design – some had rather sophisticated allusions to classical art and other aesthetic traditions – also work against any argument that his entry into creative work did not happen until his final years. “The professional path he followed did not…lead predictably to Hirshfield’s later career as a painter,” Meyer acknowledges, but “this is all the more reason to take that path seriously as a creative and entrepreneurial enterprise in its own right.” Meyer puts words to action in the exhibition space, where patent drawings and other ephemera are on view, along with modern-day recreations of Hirshfield’s slippers fabricated by artist Liz Blahd.

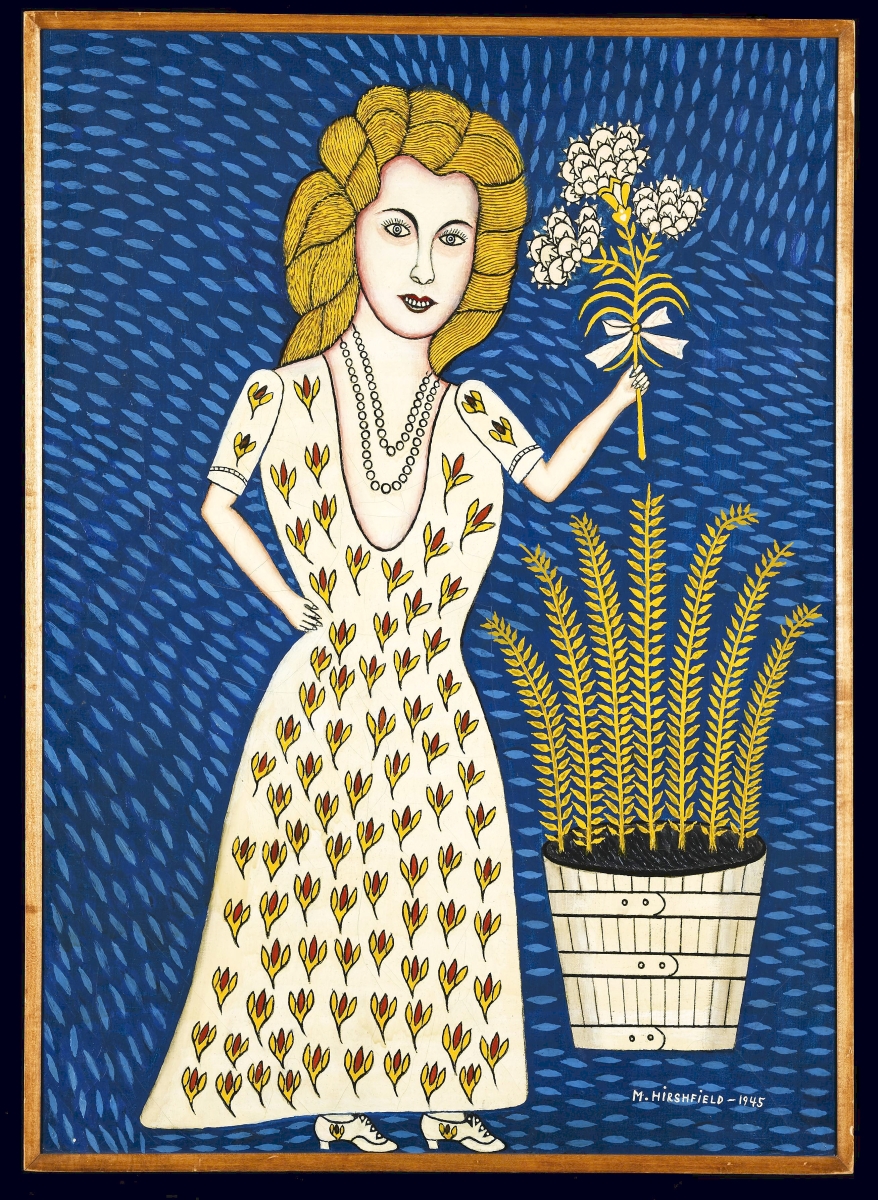

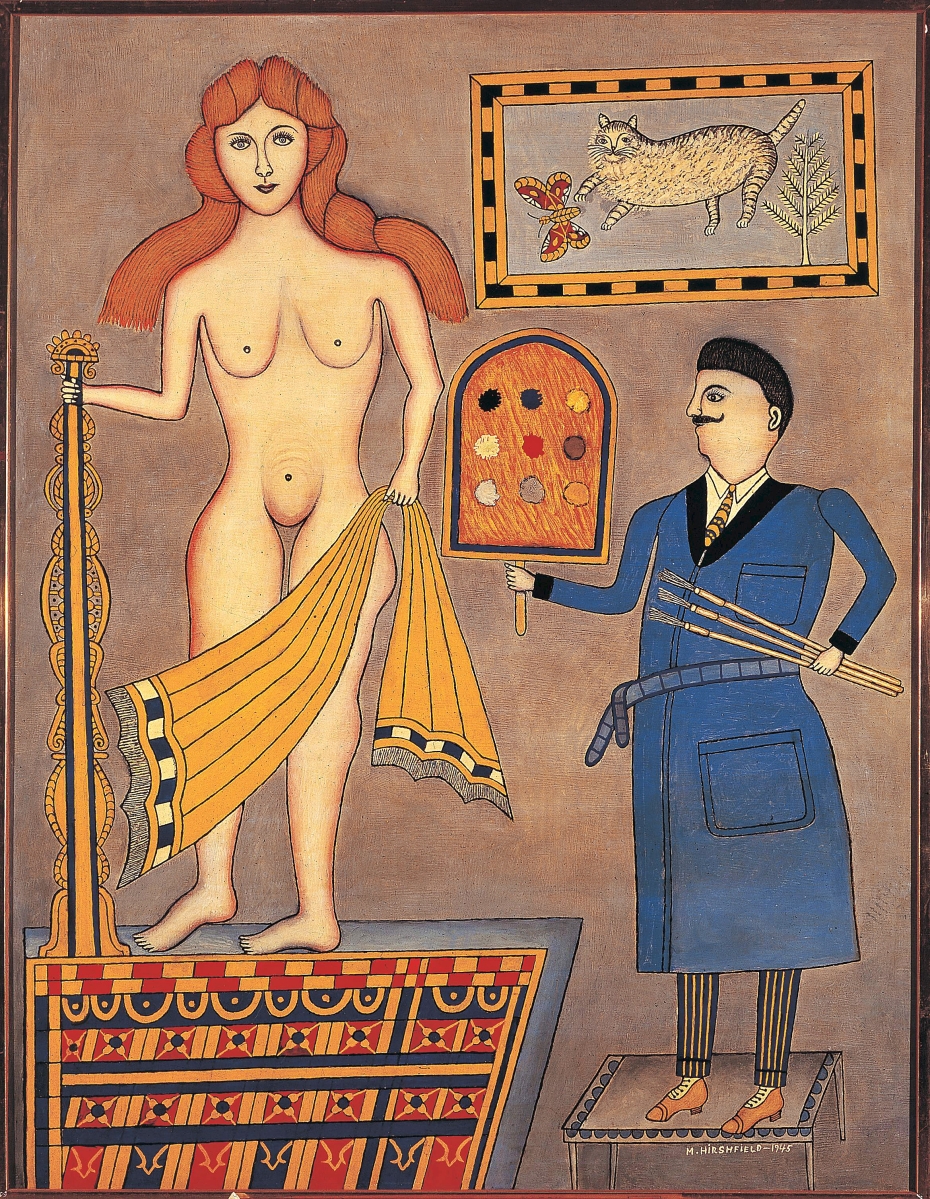

It perhaps stands to reason, then, that feet and their accouterments are rarely throwaway elements in Hirshfield’s paintings: witness the detailed footwear in “Girl in Flowered Dress,” “Stage Beauties,” “Girl with Pigeons” and even “The Artist and His Model,” where the model’s (two left) feet are bare, but the artist’s are clad in a pair of sharp, two-toned brogues. It’s clear that an attentiveness to fashion and self-presentation stayed with Hirshfield long after he sold E-Z Walk Mfg. Co. in the mid-1930s, due to his failing health. Unfortunately, the new proprietors did not share his professionalism or business acumen, and the company dissolved soon after.

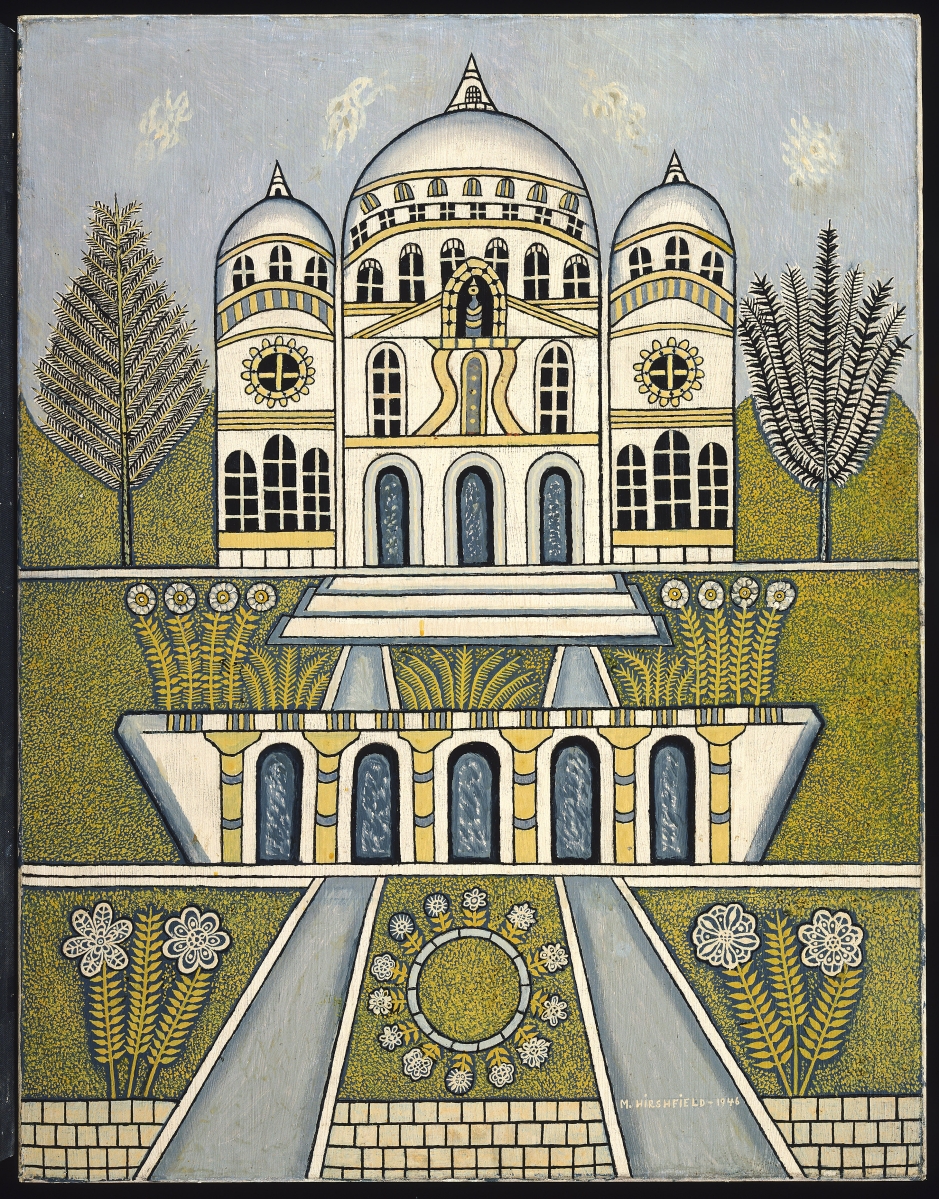

“Without a job for the first time since 1890,” Meyer writes, “he revived his long-delayed ambition to become a painter.” Much of what we know of Hirshfield’s first forays into this new professional life are filtered through Janis, who was a gifted storyteller but not, apparently, a fabulist. Janis remembered that Hirshfield’s first two efforts were painted over existing canvases from his home, “lingering possessions of his affluent days.” These seem to be “Beach Girl,” where the titular figure’s face has been “borrowed” from the original painting, while everything that surrounds her is all Hirshfield’s yarn skies and herringbone grasses; and “Angora Cat,” where the reused element is the bronze dog on a shelf behind the cat’s head.

“Angora Cat” by Morris Hirshfield, 1937-39, oil on board on canvas, 22-1/8 by 27¼ inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection, 1967, 607.1967. ©2022 Robert and Gail Rentzer for Estate of Morris Hirshfield / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

“Angora Cat” is in fact the key work in the story Janis told of how he “discovered” Hirshfield. Janis had just sold his own lucrative business in the garment industry, M’Lord shirts -the parallels between Janis’ and Hirshfield’s early life stories are remarkable – to focus on collecting and dealing art. He visited a Brooklyn gallery in search of works by “unknown” artists for his upcoming show at MoMA. On his way out, he noticed two canvases turned toward the wall. Leaning one back, he remembered, “What a shock I received! In the center of this rather square canvas, two round eyes, luminously gleaming in the darkness, were returning my stare!”

Were the paintings really rejected, turned away from the wall, “about to be cast on the dustbin of history,” as Meyer puts it? To some extent, it may not matter; there is no denying that Janis’ backing made Hirshfield’s career. Perhaps more important is to attend to the rest of what Janis tells us about this encounter: that Hirshfield had originally brought the paintings to the Brooklyn Museum; that the museum then called the gallery in to consult. These are not the activities of a hobbyist but a seasoned businessman. From the start, Hirshfield was serious about showing and selling his art, and he brought all his professional experience to bear in making that happen.

“I don’t think Hirshfield by any means was innocent of publicity or marketing or what it would mean to have a solo show at MoMA,” Meyer says. “I think he knew how to market himself as someone who didn’t know anything, because there was this appeal to the idea of a so-called ‘modern primitive.'” What Hirshfield may not have fully understood was the fickleness of the art world and its insularity, both of which contributed to the disastrous reviews of his solo show in 1943. “I think it has to do with the way in which the life – in peoples’ minds, their perception of the life – collided with their perception of the art in Hirshfield’s case,” Meyer says. “Hirshfield lived a conventional life in many ways…the Hirshfields were observant Jews, with kids who lived nearby, they were very Brooklyn-based – there’s nothing from outside that would suggest the sort of flamboyant erotics you see in the paintings.” Meyer is quick to clarify that these “erotics” include not only the nudes that the critics found so troubling, but also the “flamboyance in general about the palette and the brushwork…the critics thought it was an inexplicable choice for a solo show at MoMA.”

Meyer has spent his career grappling with outsiderness, remembering that when he wrote his dissertation on queer art back in the 1990s, he worried that it might close off certain opportunities to him. Things are different now – as a tenured professor at Stanford, he is able to take on passion projects like this one in a way that he knows others cannot. Still, he muses, “there are moments in your life where you see that what made you an outsider may be exactly what you want to retain when you have access.” He sees something like this in Hirshfield, who stayed true to his unique aesthetic – arguably leaned into it – even after taking a beating from the critics in 1943. “One of the key points in the book is that Hirshfield was creative (and self-taught) long before he was a self-taught painter in the 1940s,” Meyer says. Hirshfield trusted those creative and professional instincts all the way to the end.

The American Folk Art Museum is at 2 Lincoln Square. For more information, 212-595-9533 or www.folkartmuseum.org.

.jpg)