Cornelis Zitman (Venezuelan, born the Netherlands, 1926-2016), “Dining chair,” 1955, teak with woven enea, 33 by 20 by 22 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York City. Committee on Architecture and Design Funds. Digital image ©2024 The Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

By Laura Preston

NEW YORK CITY — Certain design objects are so common to daily life they are functionally invisible. Take, for example, the chair. Since the ancient world, chairs have been our constant, inert counterparts. They raise us from the ground, support the back, aid repose and describe the negative space around a body. This simple necessity has spawned infinite iterations. In an audit of mankind’s chairs, one will find royal thrones, the plain church pew, the pneumatic office chair, the vinyl recliner for the dental patient and the humble ladderback at a farmhouse table. Each chair makes an argument. In its materials, form and use, one will find an essay on the society that made it.

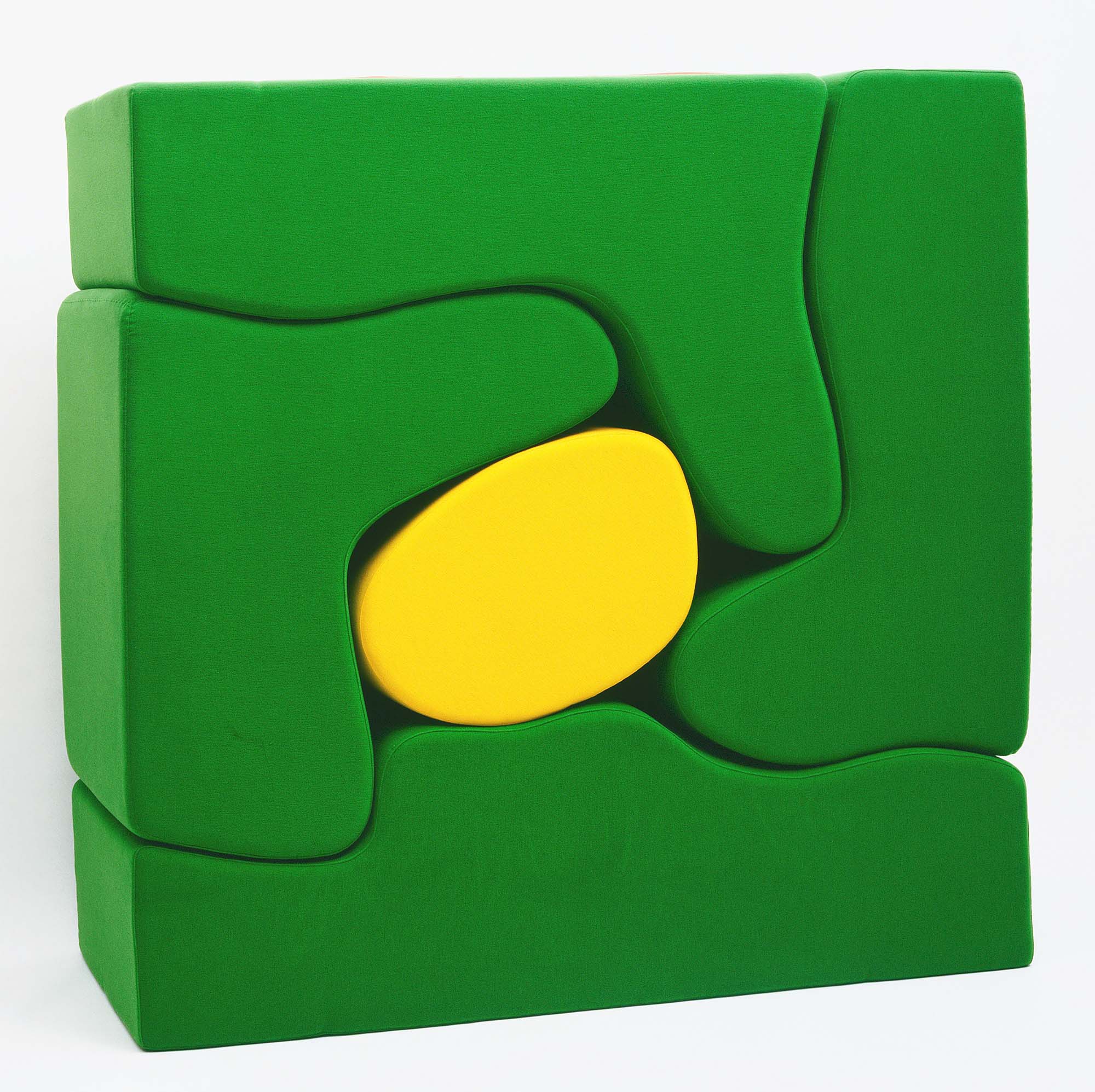

The Museum of Modern Art, New York’s (MoMA) recent exhibition, “Crafting Modernity: Design in Latin America, 1940-1980,” which runs through September 22, is a celebration of chairs. Some of these chairs will take your breath away. There is Jaime Gutierrez Lega’s Oveja armchair, with its chubby, walnut frame draped in a luscious pelt of sheepskin. There is Lina Bo Bardi’s funky, forward-thinking, Bowl chair, whose title describes its shape: a Euclidian half-sphere in plush navy fabric supported on steel legs. There is another Bo Bardi chair, the Tripé de Ferro chair, whose sling-shaped seat was inspired by the hammocks of the Amazon. There is Juan Baixas’s Puzzle Chair, with a wooden frame of interlocking parts on which can be draped a canvas seat. Then, a real showstopper: Jose Zanine Caldas’s Namoradeira Tête à Tête Lounge Chair, carved from a single trunk of salvaged wood using techniques from canoe-building, which allows two sitters to sit side-by-side, face-to-face, and cooperatively rock back and forth. The chair manages to look both modern and folky, with angles reminiscent of Pierre Jeanneret, and deep, glowing striations of grain that recall the stripes of a cat.

Installation view of “Crafting Modernity: Design in Latin America, 1940–1980,” on view at The Museum of Modern Art through September 22. Robert Gerhardt photo.

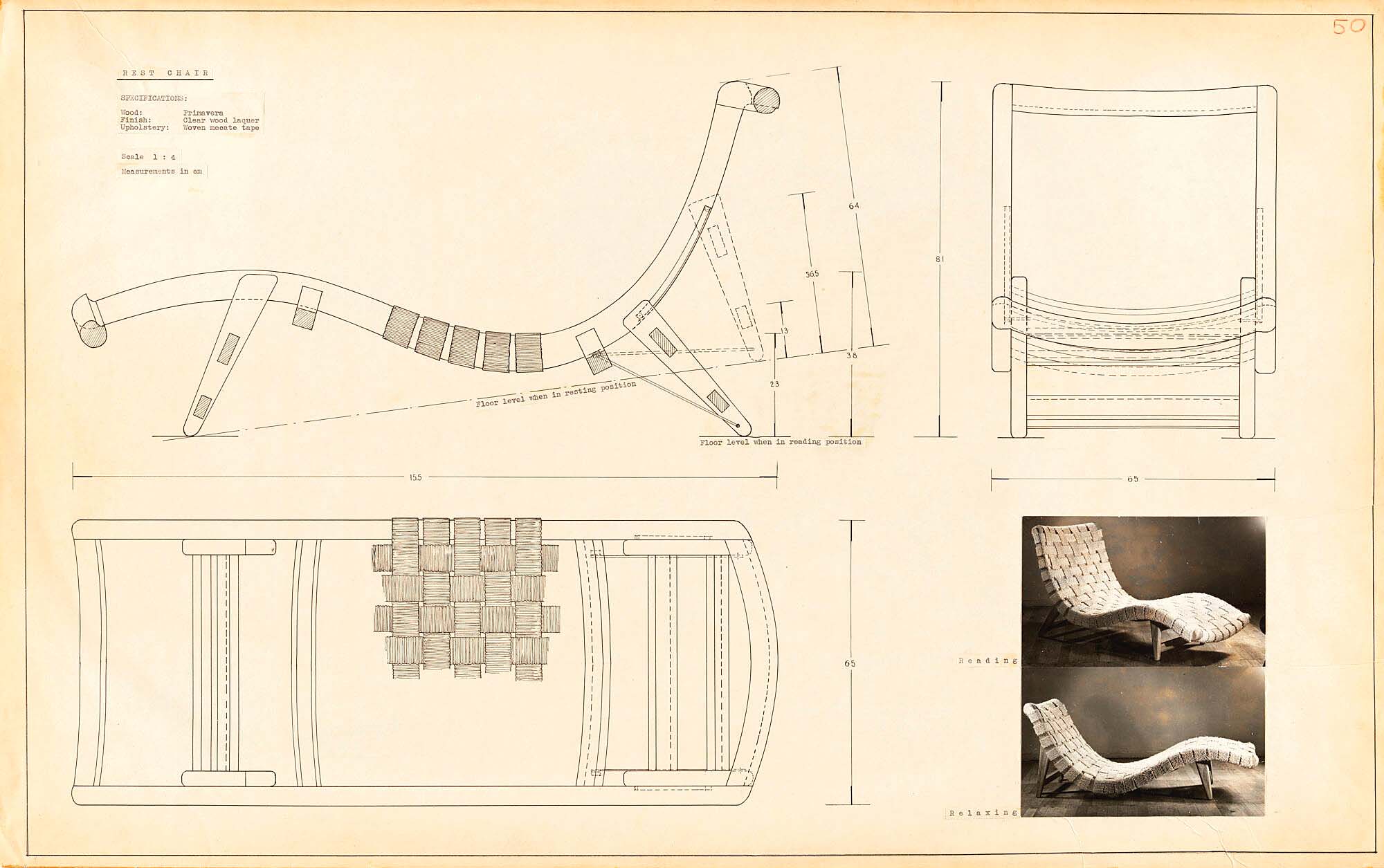

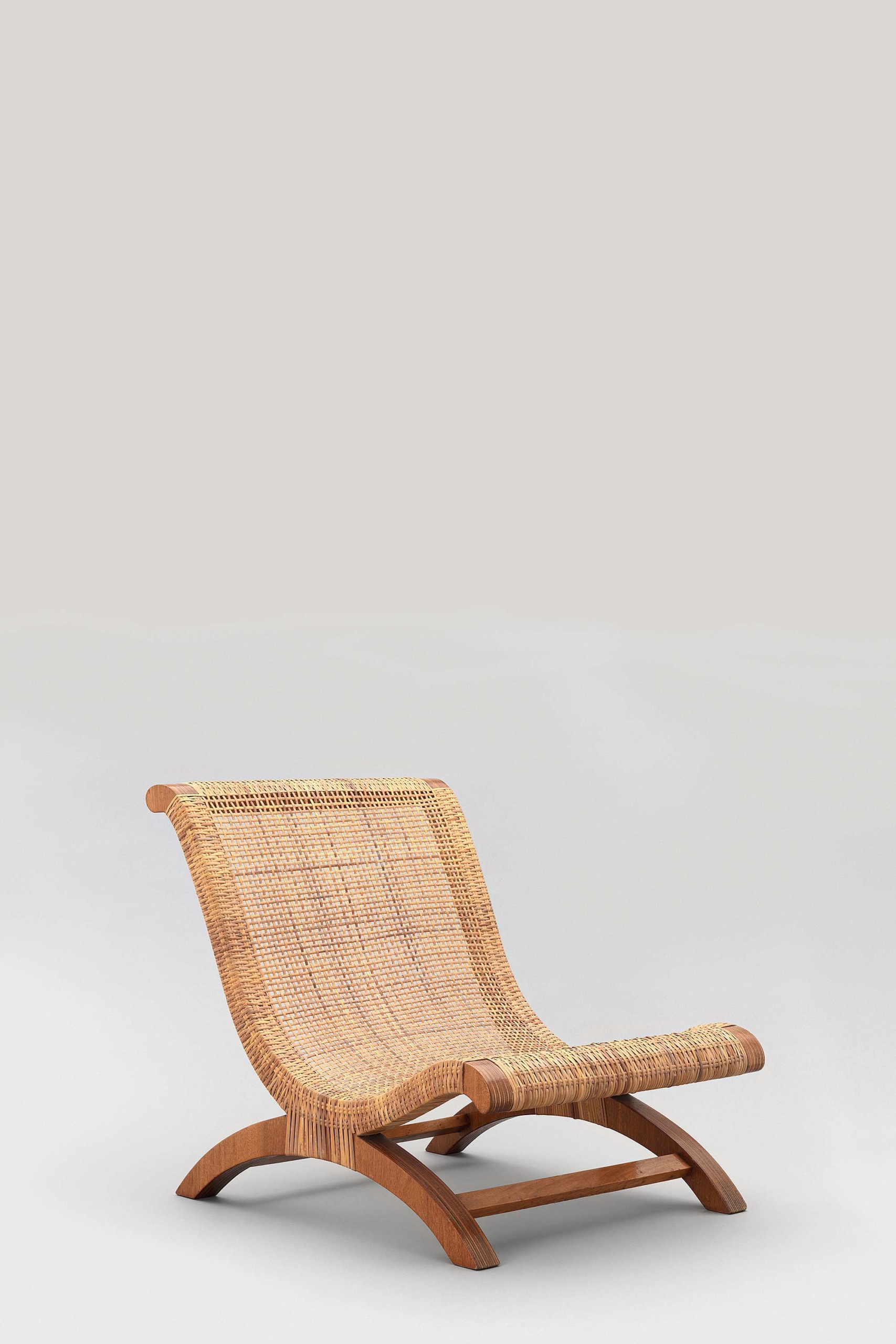

The show’s curators, Ana Elena Mallet and Amanda Forment, were motivated by a central conceit: that Latin America in the mid-Twentieth Century was not only an exuberant hub of modernism, but a laboratory of many modernisms that sometimes conflicted and sometimes rhymed. The show maps a complex network of artists and designers, many of whom studied in Europe and the United States before establishing their practices in Mexico, Argentina, Venezuela and Brazil. Many married emergent forms with local materials and Indigenous craft traditions to make surprising hybrid works. Take, for example, Cornelius Zitman’s small but lovely dining chair, which resembles contemporaneous teak and rope chairs from Hans Wegner and others. Yet Zitman wove his chair with local enea fibers, which are thicker and more varied than the usual paper cord. The material gives the woven seat and back a toothiness that is personal, handmade and compelling.

There is no better example of the marriage between modern and folk forms than Clara Porset’s Butaque chair, which is one of the show’s centerpieces. Here, Porset reinterprets the high-backed, low-slung butaque typology, simplifying it into a clean, minimalist swoop. This frame could be backed with a range of coverings: hide, leather straps or wicker, as the version in this show. While leather and hide have their charms, the wicker here is exceptional. The delicate but firm straw seat, woven by masterful local craftspeople, allows light to pass through the chair and illuminate its sculptural bones. The chair declares modern design values while honoring Indigenous weaving traditions and the regional butaque. The butaque typology is in itself a hybrid form that merges the pre-Columbian duho with the X-framed chairs of Spanish colonists. Porset’s butaque is therefore a pastiche of a pastiche, and the perfect visualization of a layered national identity.

Clara Porset (Mexican, born Cuba, 1895-1981), “Butaque,” 1957, laminated wood and woven wicker, 28¾ by 25-13/16 by 33-7/16 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York City. Gift of The Modern Women’s Fund. Digital image ©2024 The Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

Just as these design objects are sites of cultural and historical interplay, so, too, were the spaces they occupied. When arranging this exhibition, the curators faced a challenge. How does a museum convey to visitors that the objects on plinths were intended to be lived with? “When introducing a show like this, it’s difficult to not pair these items with archival material,” said Mallet. But architectural documents like floor plans are not always legible to a general public, nor do they convey the lively collisions of folk tradition and modern industry that were taking place in certain design-forward homes.

To solve this problem, the exhibition makes clever use of digital resources. As we move through the show, we encounter slideshows of four iconic houses: Enrique Yáñez’s family residence in Mexico City, Mexico; Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro in São Paulo, Brazil; Alfredo Boulton’s house on the island of Pampatar, in Venezuela; and Amancio Williams and Delfina Galvez’s Casa Sobre el Arroyo in Mar del Plata, Argentina. Some of these houses engage with their surrounding environments, creating surprising interplays of indoor and outdoor space. The Casa de Vidro, for example, is a gleaming glass rectangle partially suspended on pilotis, which allows the rainforest to grow up through the empty space beneath it. The Casa Sobre el Arroyo spans a river like a bridge. Other houses play with layered temporalities. Alfredo Boulton’s Pampatar residence was constructed with local materials and traditional techniques. Within the home, objects of modernity mingle with the past. An Alexander Calder mobile hangs near a Sixteenth Century chest, while Spanish colonial chairs sit beside modern butaques designed by Miguel Arroyo. The point, says Mallet, is that these homes were laboratories — not static monuments but organic spaces where ideas recombined and histories collided.

Installation view of “Crafting Modernity: Design in Latin America, 1940-1980,” on view at the Museum of Modern Art through September 22. Robert Gerhardt photo.

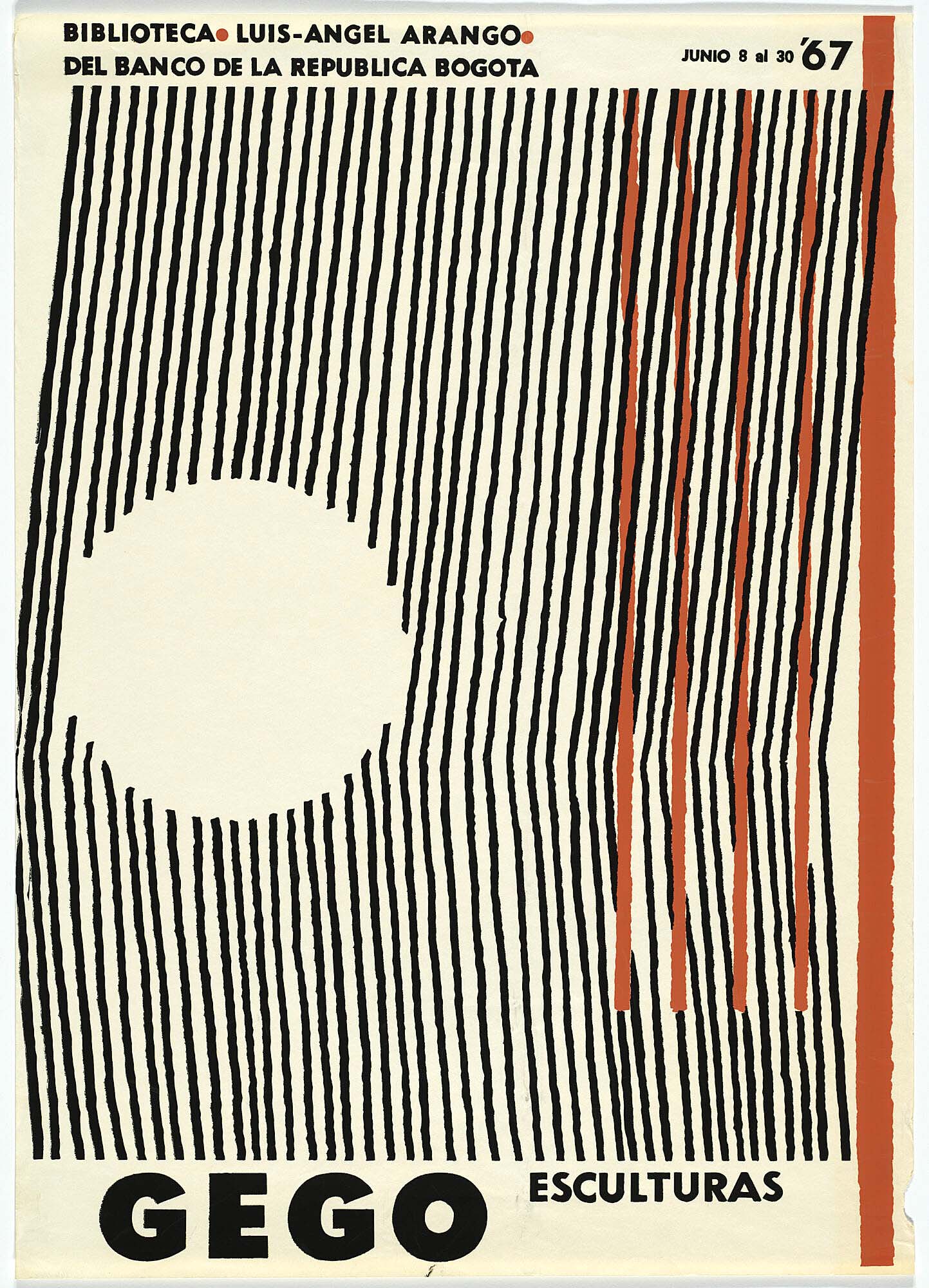

While the chairs are the clear highlights of this show, they are displayed alongside a host of other wonderful items, including textiles, which are particularly strong. A monumental weaving by Gertrud Goldschmidt, the German-Venezuelan artist better known as Gego, is an outstanding piece of work: a thick, shaggy tapestry of brown wool, more than 14 feet tall and nearly 11 feet wide. A ladder of horizontal stripes rises up the middle, while one humorous, free-thinking line interrupts their order. Like many of the items in this show, this weaving lives at the interstices. It is at once full-bodied and delicate, a household textile and a graphic field, an object of handicraft and a philosophical experiment.

Other textiles are similarly charming. A vibrant tapestry of a rooster is a wonderful example of Luis Montiel’s work. Montiel, a member of the Wayuu people, made affordable weavings that straddled Indigenous tradition and op art, and were popular in households across Venezuela in the 1960s. Meanwhile, a small figurative tapestry by Afro-Brazilian artist Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt is a revelation. Reinbolt worked her entire life as a domestic servant, most notably to the Brazilian architect Lota de Macedo Soares and her partner, the poet Elizabeth Bishop. In her spare time, she made “wool paintings” using scrap threads she stitched through burlap backings. Her exuberant, idiosyncratic scenes of people, animals and childhood memories are simply phenomenal, and the one on display here — a spirited dinner scene — is one of the best items in the gallery.

Antonio Bonet (Spanish, 1913-1989), Juan Kurchan (Argentine, 1913-1975) and Jorge Ferrari Hardoy (Argentine, 1914-1977), “BKF Chair,” 1938, painted wrought iron rod and leather, overall: 34-3/8 by 32¾ by 29¾ inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York City. Edgar Kaufmann Jr. Digital image ©2024 The Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

Overall, there is a feeling of contrition to this show, which attempts to make up for Latin America’s elision in mainstream histories of modernity. It has been 83 years since MoMA last engaged with Latin American design. In 1941, the museum staged a juried exhibition, “Organic Design in Home Furnishings,” which called on designers from the United States and Latin America to propose furniture that would slough off “the clutter of inheritance from the Nineteenth Century” to create “a better environment for today’s living.” Even then, Latin American designers were a footnote, with a mere five pages at the back of the exhibition’s 50-page booklet. The prize for American winners was a contract with a major furniture manufacturer, while the prize for Latin American winners was a trip to New York “to observe and study the work being done here.” In perusing MoMA’s current show, it seems that the conceit of 1941 — that Latin American designers should learn from American schools — is due for a reversal. Through this show, one can see the clear lineage between Latin America’s exuberant, eclectic design innovations and our contemporary tastes. Modernism, this show argues, is not a monolithic doctrine, but a river of concurrent conversations agnostic to borders.

Another way in which “Crafting Modernity” corrects the record is in its celebration of women designers who have been unfairly neglected. In the 1941 competition, Clara Porset and her husband, Xavier Guerrero, won a citation for their group of “rural furniture” made from pine and ixtle webbing, but only Guerrero was credited. Now Porset gets her due. Like any show about modernism, the gallery is full of men’s work, but the women artists are the knock-out stars: not just Porset, but Bo Bardi, Gego and Reinbolt, and also Colette Boccaro, whose sensitive ceramic work deserves close attention.

Installation view of “Crafting Modernity: Design in Latin America, 1940-1980,” on view at the Museum of Modern Art through September 22. Robert Gerhardt photo.

There is a celebratory energy to this show, with its abundance of imaginative design objects, but a sadness lingers over the display. The designs here embody the buoyancy, hope and progressive politics of the region in the middle Twentieth Century. But this future did not arrive. Through the 1960s and 1970s, a cascade of coups upended cultural production. One of the most haunting objects of the show comes near the end of the presentation: a child’s chair, by Gui Bonsiepe, designed for Chilean kindergartens as a way to merge socialist principals with common material culture. The chair sits on a plinth, pristine and unused. Though MoMA’s policy is to never display reproductions, here they made an exception. On view is a reproduction from 2017, on loan from The Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago, Chile. Within months of the chair’s design, a CIA-backed coup installed a military dictatorship. The original chairs were never made.

“The history of design in Latin America is a relatively new field,” said Mallet, who hopes that “Crafting Modernity” will introduce students to the area of study and inspire new scholarship. Mallet also anticipates that the show will be meaningful to visitors with Latin American heritage, especially during the summer months, when people travel to New York from abroad. All of the show’s gallery texts appear in both English and Spanish, so that visitors with shared heritage can identify with the works.

“We are used to the big narrative of modernism, but there are different modernisms,” said Mallet. “Crafting Modernity” makes this clear. Modernism is not a monolith, but a continuum of material, formal and historical exchange. It is an endless global conversation, a life force, a system of roots without a center.

The Museum of Modern Art is at 11 West 53rd Street. For additional information, 212-708-9400 or www.moma.org.