By Kate Eagen Johnson

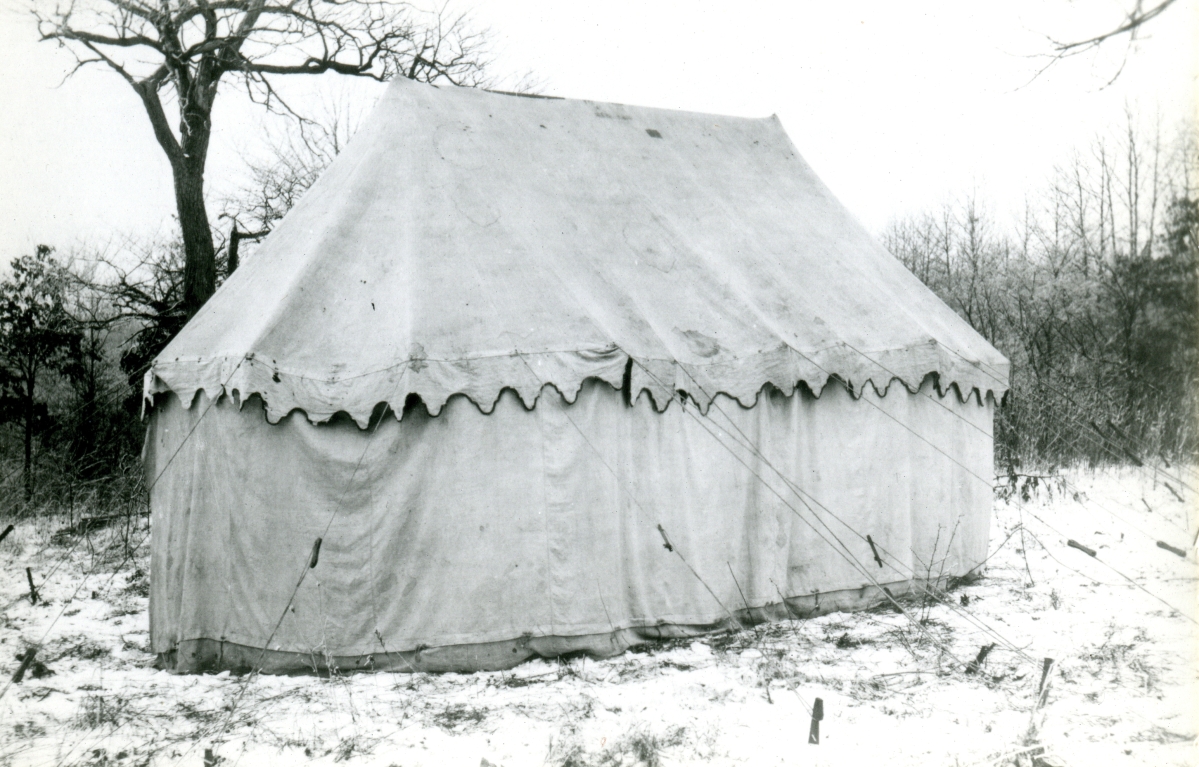

PHILADELPHIA, PENN. – “I refer to it as a century-old startup. Our roots go back to Reverend Burk and his 1909 acquisition of the George Washington war tent, which we call the ‘first oval office.'” R. Scott Stephenson thus characterized the Museum of the American Revolution, where he serves as vice president of collections, exhibitions and programming. The newest star in Philadelphia’s firmament of cultural institutions opens its state-of-the art building designed by Robert A.M. Stern Architects on April 19. The museum explores the story of the nation’s formation through a major exhibition of some 450 artifacts, interactive displays and dynamic recreated environments.

Brigadier General John Muhlenberg of Trappe, Penn., carried these pistols engraved “PM” during the Revolutionary War. He led the Eighth Virginia Regiment, a corps of largely German-speaking soldiers from the Shenandoah Valley. Pistols, London, 1750–60. Walnut, brass, iron and steel.

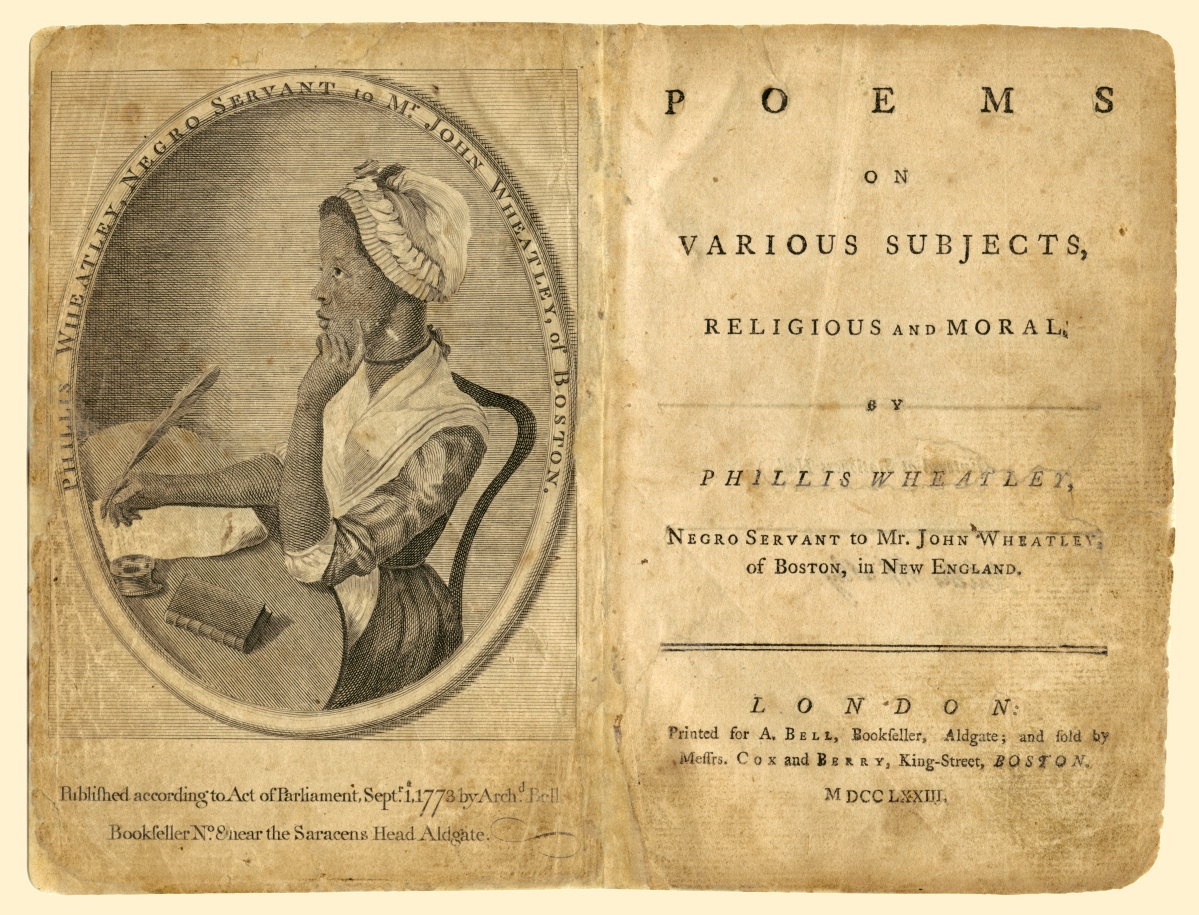

It all began in 1909 when antiquarian Reverend W. Herbert Burk (1867-1933) acquired General Washington’s field tent for the Valley Forge Museum of American History, later called the Valley Forge Historical Society. With the dream of creating a museum honoring Valley Forge’s role in the War for Independence, Burk raised $5,000 to purchase the iconic object from Mary Custis Lee, Martha Washington’s great-great-granddaughter and Robert E. Lee’s daughter. Over the decades, Burk and his successors assembled an extraordinary array of military and domestic Revolutionary War-related artifacts and publications even as the collection lay slumbering in warehouse storage.

In the tale of institutional progression, the Valley Forge Historical Society preceded the American Revolution Center, which later became the Museum of the American Revolution. The society’s collection was transferred to the new organization in 2003. When the project began, no museum was dedicated to telling the story of the American Revolution as a whole, according to president and chief executive officer Michael Quinn. Stephenson added, “During the mid-2000s, museum chairman H.F. “Gerry” Lenfest became very excited, considering the project long overdue and something that the nation needed.”

The nonprofit organization has completed a $150 million campaign to construct the building, install the core exhibition and create an endowment. Lead gifts came from Lenfest, the Commonwealth’s Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program and the Oneida Indian Nation.

Discussing his firm’s approach to the design of the museum building, Robert A.M. Stern commented that while some current practitioners view architecture as self-portraiture, he and his team aim “to portray the institution we are asked to serve.” Stern emphasized, “We have done our best to address its context,” pointing to the neighboring historic structures of Independence Hall, Carpenter’s Hall and the First Bank of the United States. The 118,000-square-foot facility, devised to achieve Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) gold certification, contains core and temporary exhibition galleries, educational and collections-support spaces and visitor amenities. The building was erected where a Bicentennial visitors’ center had once stood, a site made available through a 2010 land exchange with the National Park Service for 78 acres near the Schuylkill River in Valley Forge. The museum is envisioned as a tourism portal for historical and cultural attractions in Center City and elsewhere in Philadelphia.

The powder horn belonging to Virginian rifleman William Waller is inscribed “Liberty or Death,” “Willm Waller,” “Appeal to Heaven” and “Kill or be Killd.” British and Hessian troops captured him after the fall of northern Manhattan’s Fort Washington on November 16, 1776. Powder horn, Virginia, 1775–76. Horn (cow), wood, brass and ink.

Asked about his own participation in the project, Stephenson reflected, “It’s been an evolving role over the past ten years. It started in January 2007 when I was inventorying and cataloging the collection from the Valley Forge Historical Society…. Collecting had continued into the 1980s and 1990s. We were in an accessioning mode and I was working on how objects would form the basis of the museum’s exhibitions.”

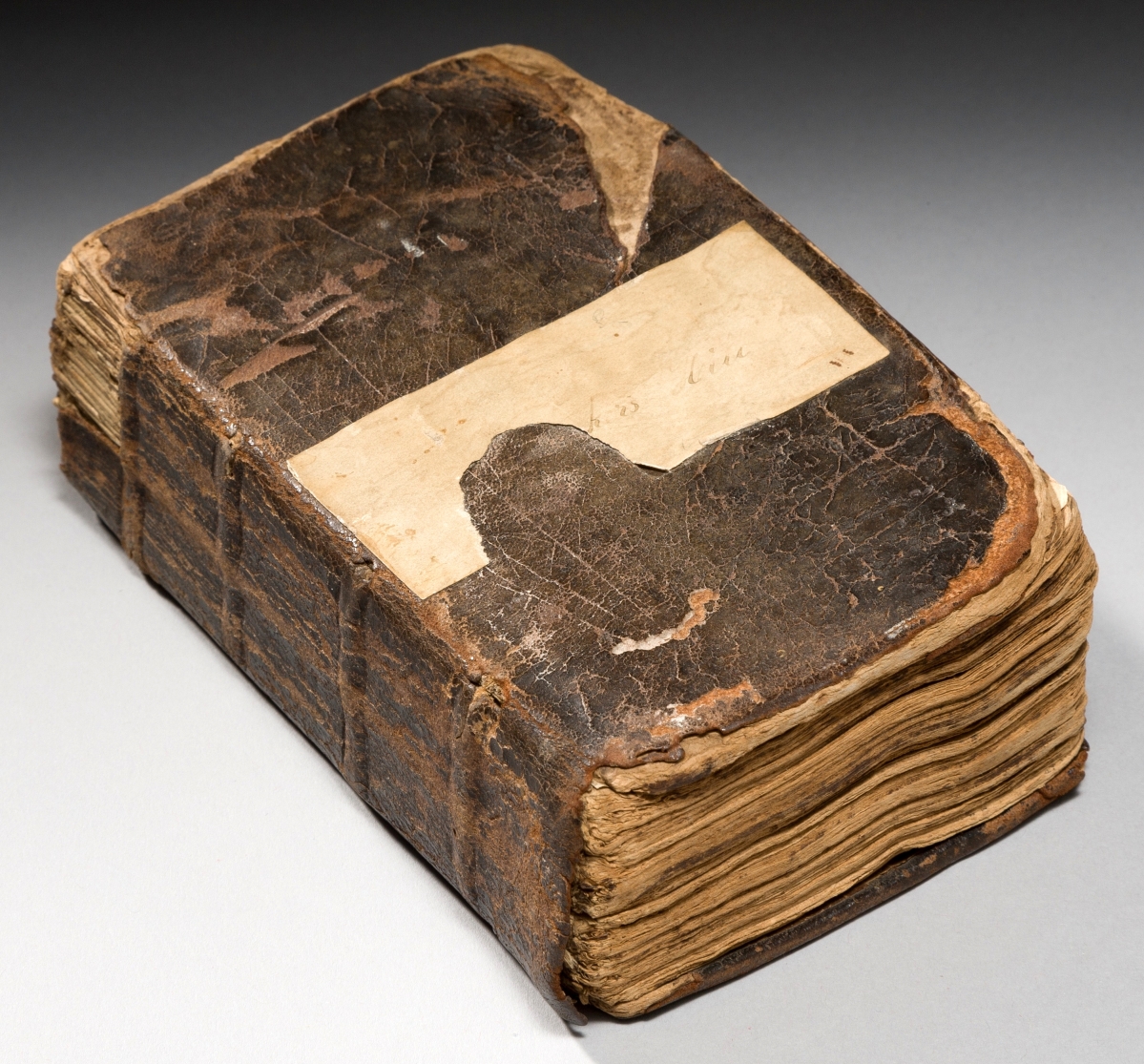

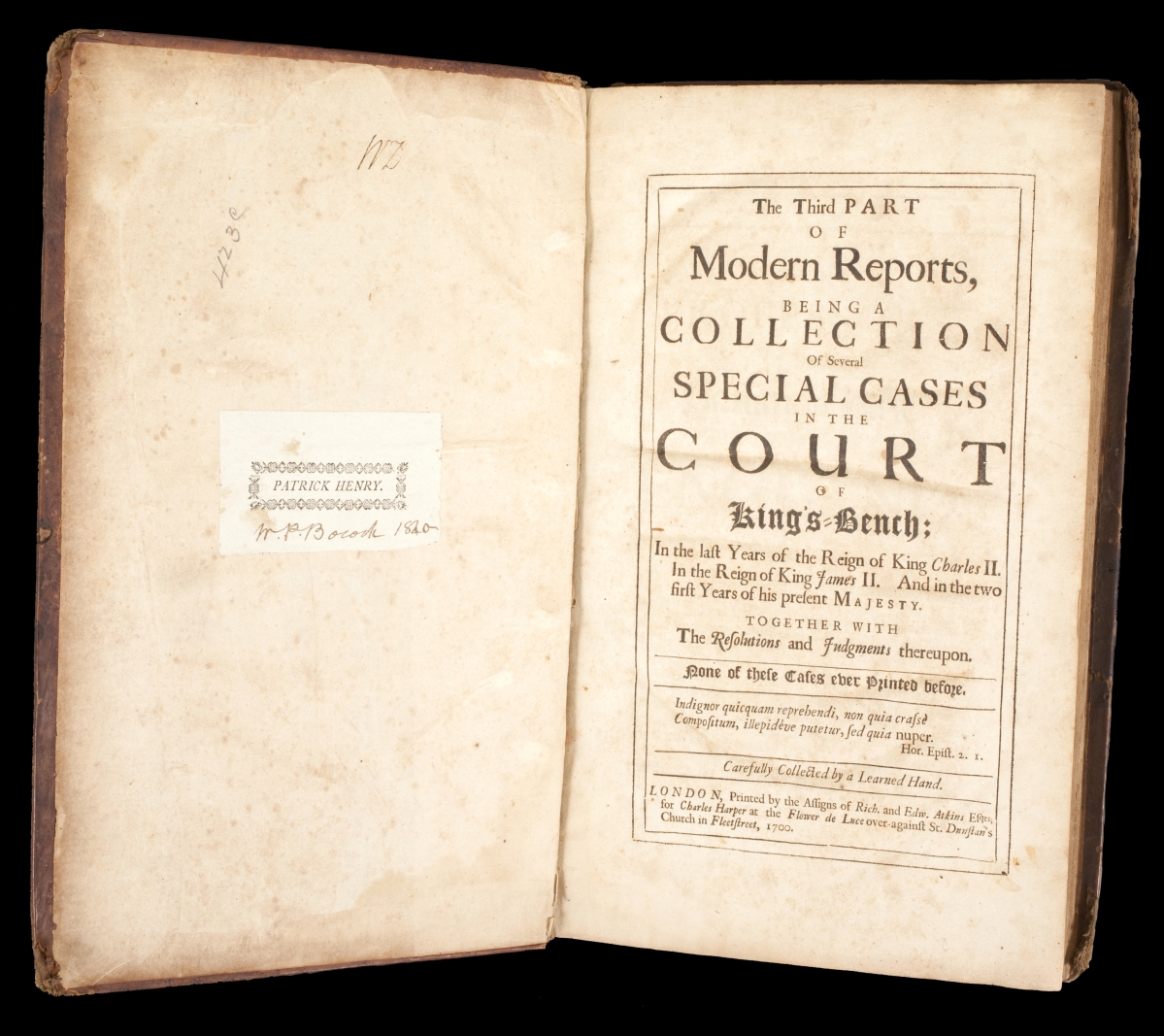

To suggest the flavor of the discovery phase, Stephenson shared a story. He described the time he was methodically unpacking a box, pulled out a leather-bound volume and opened it to find a simple bookplate stamped in printer’s type “Patrick Henry.” It turned out to be one of five law books, three of which bore Henry’s bookplate. Upon investigation, Stephenson located all five titles on Henry’s 1799 probate inventory. Stephenson also came across the catalog for the 1910 auction where Henry’s descendants had sold the books and Reverend Burk had purchased them. “So I was finding treasures and then doing the research and getting my arms around the collection we had inherited.”

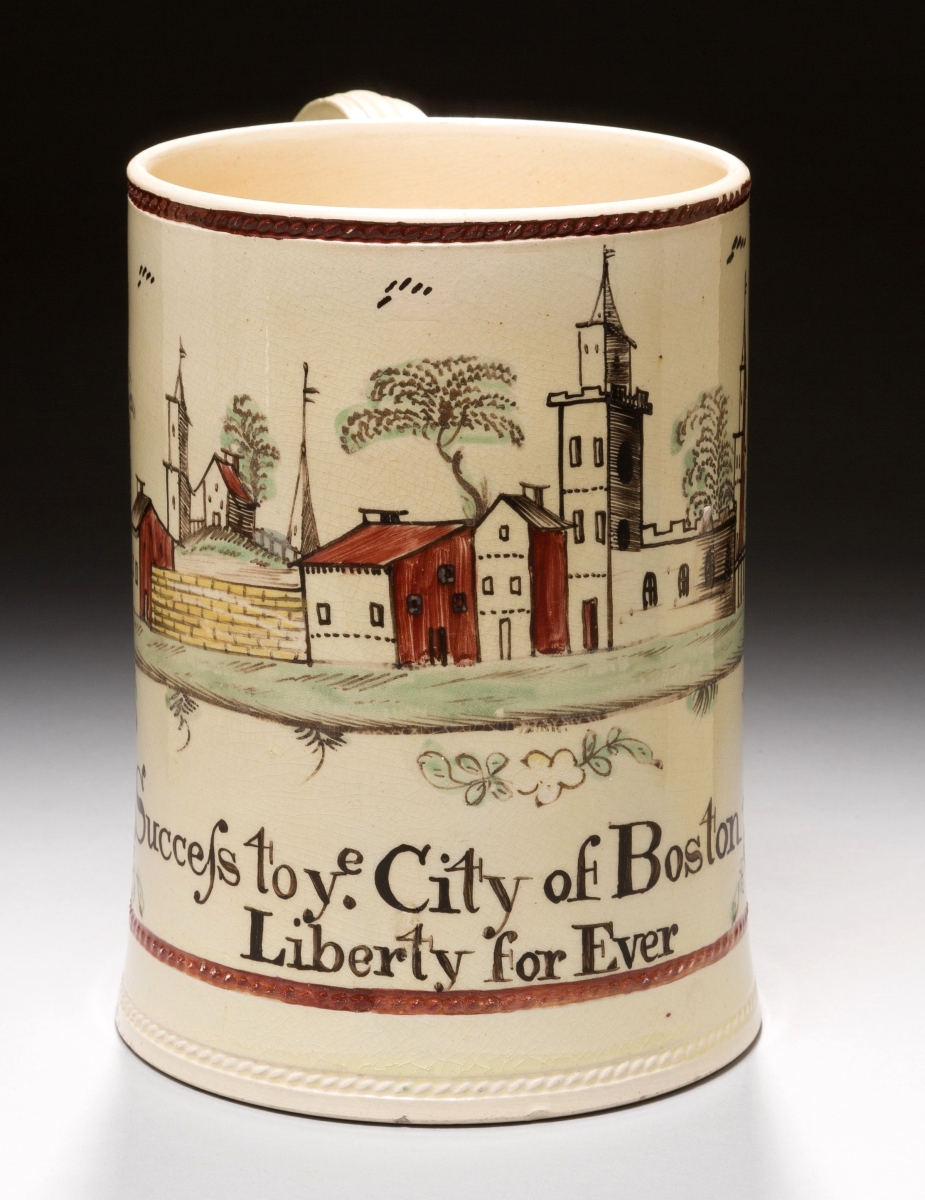

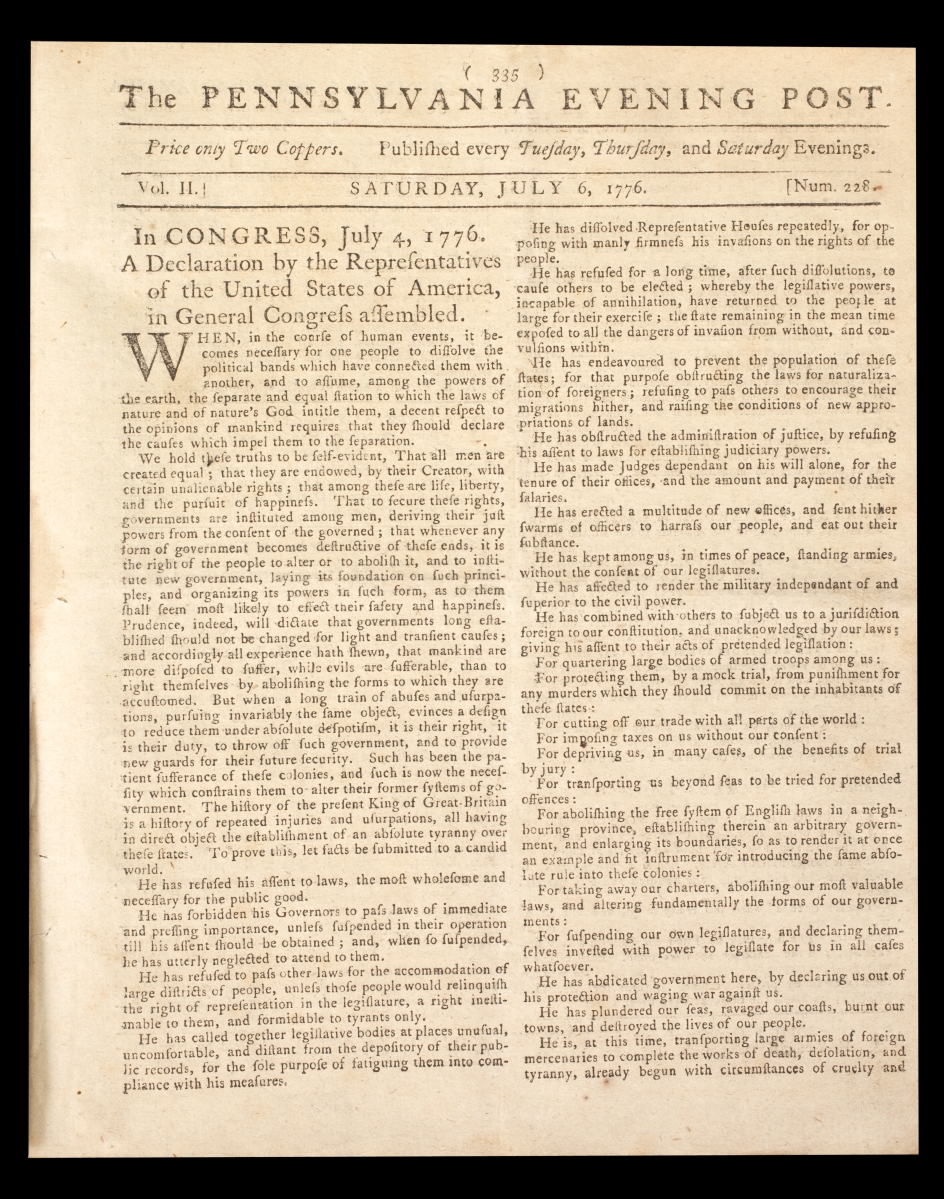

Other historical riches were literally unearthed. Archaeological investigation was conducted on the future site of the museum at Third and Chestnut Streets. Stephenson told how he happened to visit crew members on the day they were starting on the circa 1780 privy of the Humphreys family, who ran an unlicensed tavern there. He laughingly put in an order for a “No Stamp Act” teapot. Not two hours later, the head of the crew was texting him photographs of shards of a bowl with a ship depicted on its interior bottom. Eventually 90 percent of the punch bowl inscribed “Success to the Triphena,” a variation on the actual ship name Tryphena, would be recovered.

Stephenson determined that the vessel had sailed between Liverpool, Philadelphia and Charleston – and sometimes to the West Indies – during the 1760s and 1770s. In December 1765, it carried a petition signed by 300 Philadelphia merchants to the merchants and manufacturers of Britain asking them to intercede with Parliament and urge repeal of the Stamp Act. Stephenson crowed, “So didn’t they find it!” This emblematic tin-glazed earthenware bowl has been conserved and will be on display in the exhibition.

This canvas commemorating one of the Patriot Army’s most difficult times was exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1883. “March to Valley Forge” by William B.T. Trego, Philadelphia, 1883. Oil on canvas.

Examples of other historical gems retrieved from the privy include a windowpane inscribed with neighbors’ names as well as a quotation from Cato’s Letters, a collection of political essays popular among America’s revolutionaries, and the earliest hard-paste porcelain of American manufacture, a fragmentary bowl attributed to Philadelphia’s Bonnin and Morris Factory. While neither the windowpane nor the porcelain bowl will be on view when the museum opens, those interested can read about the latter in the Ceramics in America 2016 article “An Eighteenth-Century American True-Porcelain Punch Bowl” by Robert Hunter and Juliette Gerhardt. In all, more than 82,000 archeological fragments were uncovered at the site.

Exhibition concepts were developed based on collection strengths, with additional objects required to amplify the narrative secured through gift, purchase and loan. That said, artifacts are not asked to carry the entire exhibition. The story is related through multiple perspectives, including the diverse opinions and circumstances of African Americans, Native Americans, women and Loyalists. Immersive environments evoke Colonists gathering for political discourse under Boston’s Liberty Tree, irate New Yorkers pulling down the equestrian statue of King George III on Manhattan’s Bowling Green, members of the Oneida Nation debating whether or not to break from the Iroquois Confederacy and fight on the Patriots side, and British troops charging at the Battle of the Brandywine.

Stephenson remarked, “We tell a story set in wartime, not simply the story of a war. The museum is not an encyclopedia of a war. Visitors start the exhibition as subjects of a monarchy and by the end they are citizens of a New Republic.” Four overarching questions help guide them through this journey. How did people become Revolutionaries? How did the Revolution survive its darkest hour? How revolutionary was the war? What kind of nation did the Revolutionaries create?

Lieutenant James Grant of the 77th Regiment, a Highland Scottish Regiment, owned this campaign chest. Great Britain or North America, 1757–63. Wood and iron.

Plainly, Stephenson has thought a great deal about public understanding of this crucial but sometimes misunderstood era, noting that there is often a conflation of the American Revolution and the Revolutionary War. The Founding Fathers defined the term “American Revolution” variously, said Stephenson. The museum’s approach most closely aligns with Benjamin Rush’s. In his 1787 “Address to the People of the United States,” Rush asserted, “The American war is over: but this is far from being the case with the American Revolution. On the contrary, nothing but the first act of the great drama is closed. It remains yet to establish and perfect our new forms of government; and to prepare the principles, morals, and manners of our citizens, for these forms of government, after they are established and brought to perfection.”

Through engaging exhibition techniques, which won’t be revealed here, visitors are reminded in the most immediate way that they are the future of the American Revolution.

As for the curatorial department’s own future, staff will be rotating objects in the core galleries while attending to the temporary exhibition galleries expected to open in the fall and winter of 2018. For both initiatives, Stephenson and his colleagues will draw upon the approximately 3,000 objects in the museum’s collection as well as borrowed items.

Revolutionary War-era players and events have been on the rise in the public’s collective consciousness as teenagers sing and rap along to the cast album of Hamilton and as their elders consume one or more of the recently published Founding Father biographies and find themselves contemplating Liberty and Equality as more than abstractions. Then again, perhaps the subject had nowhere to go but up. A 2010 Marist Poll found one in four Americans did not know which country the Thirteen Colonies had fought to gain independence. The ambitious and impressive Museum of American Revolution launches just in time to catch this wave of popularity. Scott Stephenson invites readers “to make a beeline to Philadelphia and tell us how we did.”

The Museum of the American Revolution is at 101 South Third Street. For more information, www.amrevmuseum.org or 877-740-1776.

Kate Eagen Johnson is an expert in American decorative arts and an independent museum consultant, historian, lecturer and author.