Portrait of Nathaniel Rochester (1752-1831). Courtesy Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Rochester.

By Justin W. Thomas

NEWBURYPORT, MASS. — There has always been a question as to who the potter or potters were that worked at Colonel Nathaniel Rochester’s (1752-1831) pottery business in West Bloomfield, N.Y., circa 1818-31, seeing that he was just the business owner. But there has never been an accurate answer to this question, although it does appear that this part of Western New York was an area that some potters trained in before relocating elsewhere in the region, to establish their own business. One particular potter, Alvin Wilcox (1801-1862) is known to have trained a group of potters at another West Bloomfield business, and at least one of whom relocated to operate some sort of relatively unknown red earthenware pottery to the south of Buffalo, perhaps as early as the late 1840s and the 1850s.

Following the American Revolution, the land in Western New York opened up for settlement and many of the people who relocated to this area came from New England, Pennsylvania and Maryland. Rochester was among those settlers, moving from Hagerstown, Md., to 155 acres of land that he had purchased in Dansville, N.Y., during a prior trip to the Genesee Country in September 1800.

Colonel Rochester led a procession of carriages bearing the younger children and women of the household and three great Conestoga wagons with household goods, 10 enslaved African Americans and some of his neighbors who came along to help. The 275-mile journey lasted three weeks. The Colonel moved north, he said, “to escape the influence of slavery, to set his slaves free and to rear his family in a free state.”

This is the house Nathaniel Rochester built in Dansville, N.Y., about 1797, now on the grounds of the Genesee Country Village & Museum.

In Dansville, Rochester purchased a plank house, which is believed to have been built around 1797 that was saved from demolition in 1987 and moved to the grounds of the Genesee Country Village & Museum. Once settled in Dansville, Rochester purchased most of the water rights at Canaseraga Creek. He also erected a large paper mill and a gristmill, whereas, in the meantime, Rochester began to survey the 100-acre tract at the falls of the Genesee River that he and his colleagues had purchased in 1803.

After five years in Dansville, Rochester moved to a large farm in East Bloomfield, N.Y., and continued his work laying out what would become the Village of Rochester. In 1818, he and his family finally moved near the falls into a house with a large garden and grounds sloping down to the river. It was also around 1818 that he established a rather sophisticated pottery business, and in 1824, he built a brick house, where he resided for the rest of his life.

A circa 1820 slip-decorated red earthenware jar attributed to Nathaniel Rochester Pottery in West Bloomfield, N.Y. The jar was previously owned by R. Scudder Smith, founder and publisher of Antiques and The Arts Weekly. The personal collection of Gene and Nancy Pratt.

The red earthenware produced at the Rochester Pottery in West Bloomfield is unquestionably some of the most colorfully decorated wares made anywhere in Western New York, and perhaps anywhere in the state. Much of the known pottery is adorned with various colors of slip-decoration, where the known forms include various types of jars and pitchers. However, there is certainly a lot more to be learned about this business in terms of shapes that were produced and the inspiration for some of the more unusual decorations, such as imitating some English mochaware design. But the big question really does surround the idea of who the potter or potters were that worked for Nathaniel Rochester. There is a possibility that Rochester may have recruited a potter from the Hagerstown area when he initially decided to open a pottery. Although, I have always questioned whether there were any African Americans employed at his business, seeing that he supported the abolition of slavery while in New York, even though he did own slaves in Maryland.

But while the pottery produced on Rochester’s property is rather well known today, it may not be as widely known that a portrait of Rochester is owned by the Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Rochester. According to the museum, “This formal gentleman is the founder of the city of Rochester, N.Y. His portrait was originally thought to have been painted by James John Audubon (1785-1851), but current scholarship has weighed in against that opinion. Born in Virginia, Nathaniel Rochester was an enterprising individual, which was a characteristic of many early settlers. He founded businesses and churches, and he held governmental positions. He was the first president of the Rochester Athenaeum, the precursor to the Rochester Institute of Technology, and he was instrumental in the organization of Monroe County and the building of the Erie Canal. His practical and inventive bent may have led him to wear four-lens spectacles, which allowed him to read small print and see at a distance using the same pair of glasses.”

A circa 1820 slip-decorated red earthenware jar attributed to the Nathaniel Rochester Pottery in West Bloomfield, N.Y., collection of George R. Hamell, Courtesy Rochester Museum & Science Center.

Rochester and Buffalo also became canal cities in Western New York, which transformed the area’s trade ability, although since Colonel Rochester had a big involvement with the Erie Canal, then it is possible that he utilized the waterway to ship some of his company’s pottery production to other locations.

The site of the Rochester Pottery was excavated by archaeologist and museum specialist George R. Hamell and archaeologists from the Rochester Museum & Science Center in the 1970s, where a large assemblage of artifacts were recovered. The red earthenware sherds revealed a wide range of slip-decorated dishes produced there, much of which is very similar to pottery produced in Pennsylvania and throughout the Mid-Atlantic region. There was also a broad spectrum of glaze colors, including a bright green glaze, along with a wide variety of jars.

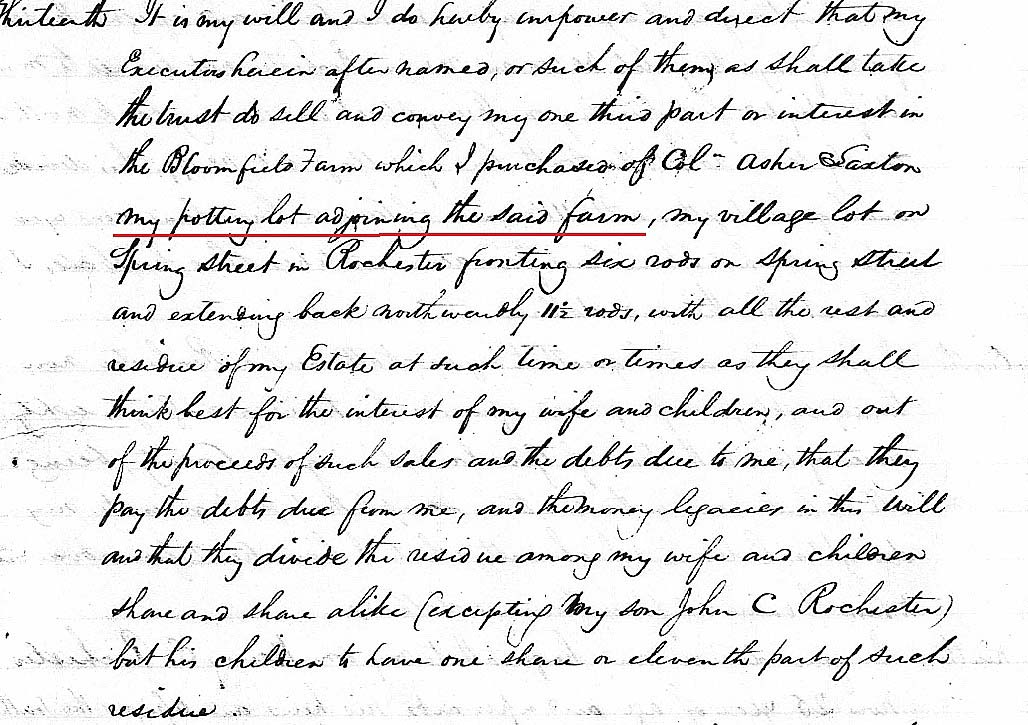

Furthermore, while conducting some archival research recently for my forthcoming two-volume book, titled, America’s Great Awakening and Migration: The Red Earthenware of Western New York, I came across Nathaniel Rochester’s three-page handwritten will in probate records from Monroe County that was previously unknown to me and many others.

The location of Nathaniel Rochester’s pottery business in West Bloomfield, N.Y.

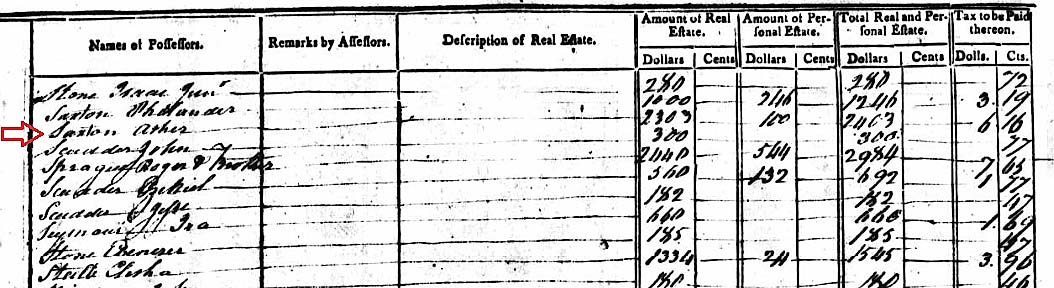

The will notes Rochester’s massive net worth, farm, pottery business and estate holdings, which were left to various family members upon his death in 1831. Within the will, Rochester states that his pottery business was located next to his farm, but he does not identify the name of any potter. However, he did write that he purchased the land that he used for the red earthenware business from Colonel Asher Saxton (circa 1747-1818), a landholder in West Bloomfield. According to the 1802 United States Tax Assessment Rolls of Real and Personal Estates, Saxton owned $2,303 worth of West Bloomfield real estate.

It is also worth mentioning that, based on the wording of Rochester’s description of his pottery business in 1831 (or thereabouts when the will was written), it would appear that he had already ceased production of the pottery company. Therefore, it is most likely that much of this company’s production dates from the 1820s period and earlier. It has also been a topic of discussion about what happened to the potter or potters once the business closed. Did they stop producing pottery or did they relocate elsewhere in Western New York or even to another state? Nonetheless, the surviving wares associated with the Rochester Pottery and the archaeological findings undoubtedly prove that it was a highly accomplished business.