“Portrait of Emily Crane Chadbourne” by Tsuguharu Foujita, 1922, tempera and silver leaf on canvas. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Emily Crane Chadbourne, 1952.997. ©Foujita Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City, 2023.

By Kristin Nord

WASHINGTON, DC — The women featured in “Brilliant Exiles: American Women in Paris, 1900-1939” were an astonishing lot…remarkably creative and innovative, and eager to proclaim their independence from the lives they had left behind. Robyn Asleson, curator of paintings and drawings at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), has taken obvious pleasure in assembling a scrapbook of this historic pantheon, women as diverse as Isadora Duncan and Josephine Baker, Gertrude Stein and Sylvia Beach, Augusta Savage and Anais Nin. The exhibition combines portraits with biographies on these women.

“Each could be a novel in herself,” Asleson said recently, and a number of them, notably Mina Loy and Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, have been on the radar lately in significant solo shows, at Bowdoin College Museum of Art and the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, respectively. Asleson, who is curating the exhibition, has also overseen the creation and publication of its 288-page catalog, a joint venture of the NPG and Yale University Press, which will be available after May 28.

“At the dawn of the Twentieth Century,” she writes in one of the catalog’s essays, “the mythic stature of Paris as the epicenter of modern innovation, personal liberty and diversity made the city a beautiful destination.” These women would help redraw the cultural map, and their contributions, in art, literature, music, fashion, publishing, journalism, theater, interior design and dance, she says, would be significant. They were early influencers, for sure, casting off the clothes and the societal expectations that had constrained them.

“Greek Dance, Neuilly” by an unidentified artist, circa 1906, gelatin silver print. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Alice Pike Barney Papers, Accession 96-153.

The artist Anne Goldthwaite reports on just such a transformation of her friends Ethel Mars and Maud Hunter Squire: “They were nice Middle Western girls in tight, plain gray tailor-made suits, with a certain primness. This was in September. By May you would never have known they came from Springfield…Miss Mars had acquired flaming orange hair, and both were powdered and rouged around the eyes until you could scarcely tell whether you looked at a face or a mask.”

The sculptor Nancy Elizabeth Prophet presented herself as a regal high priestess, often wearing her distinctive bibbed blouse, dark skirt, cloak and signature jewelry. Gertrude Stein dressed in androgynous brown corduroy robes and sandals, while her longtime partner, Alice B. Toklas, wore ultra-feminine frocks and hats. In just a few years’ time, Mina Loy would go so far as to dress herself as a lampshade for the legendary Blindman’s Ball in New York City.

Socialites Agnes Ernst Meyer and Katharine Nash Rhoades clung to couture even as they sought to escape their seemingly predestined patrician lives. Meyer became a journalist, but after returning to New York and sensing “a conspiracy to flatten out my personality and cast me into a universal mold called ‘woman,’” she plunged back into that avant-garde milieu that had so invigorated her in Paris.

“In Exaltation of Flowers: Rose – Geranium (Katharine Rhoades)” by Edward Jean Steichen, 1910-13, tempera and gold leaf on canvas. Art Bridges. ©2023 The Estate of Edward Steichen/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

Rhoades and Frances Cranmer Greenman were deeply influenced by the Fauvists and embraced vibrant color and unblended brushwork. Marguerite Zorach (née Thompson) was establishing the foundation for a multi-faceted career as a painter, textile artist and graphic designer.

As these women tested their independence, there would be some blowback. Asleson says it was hard to miss the parallels of the “Me Too” movement when she encountered tales of Rhoades fending off the advances of the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. And yet sitting for him for her photographic portrait, Rhoades appears to be fully in control. She is gazing directly into the camera, out from under a hat crowned with feathers.

Remarkably, for Black women, Asleson writes, “Paris seemed untouched by the stultifying effects of racial discrimination and segregation they had experienced in the United States. The City of Light earned a reputation for being magical, and African American women artists, writers, intellectuals and performers deserved that touch of magic in their lives if they could afford the price of an international ticket.”

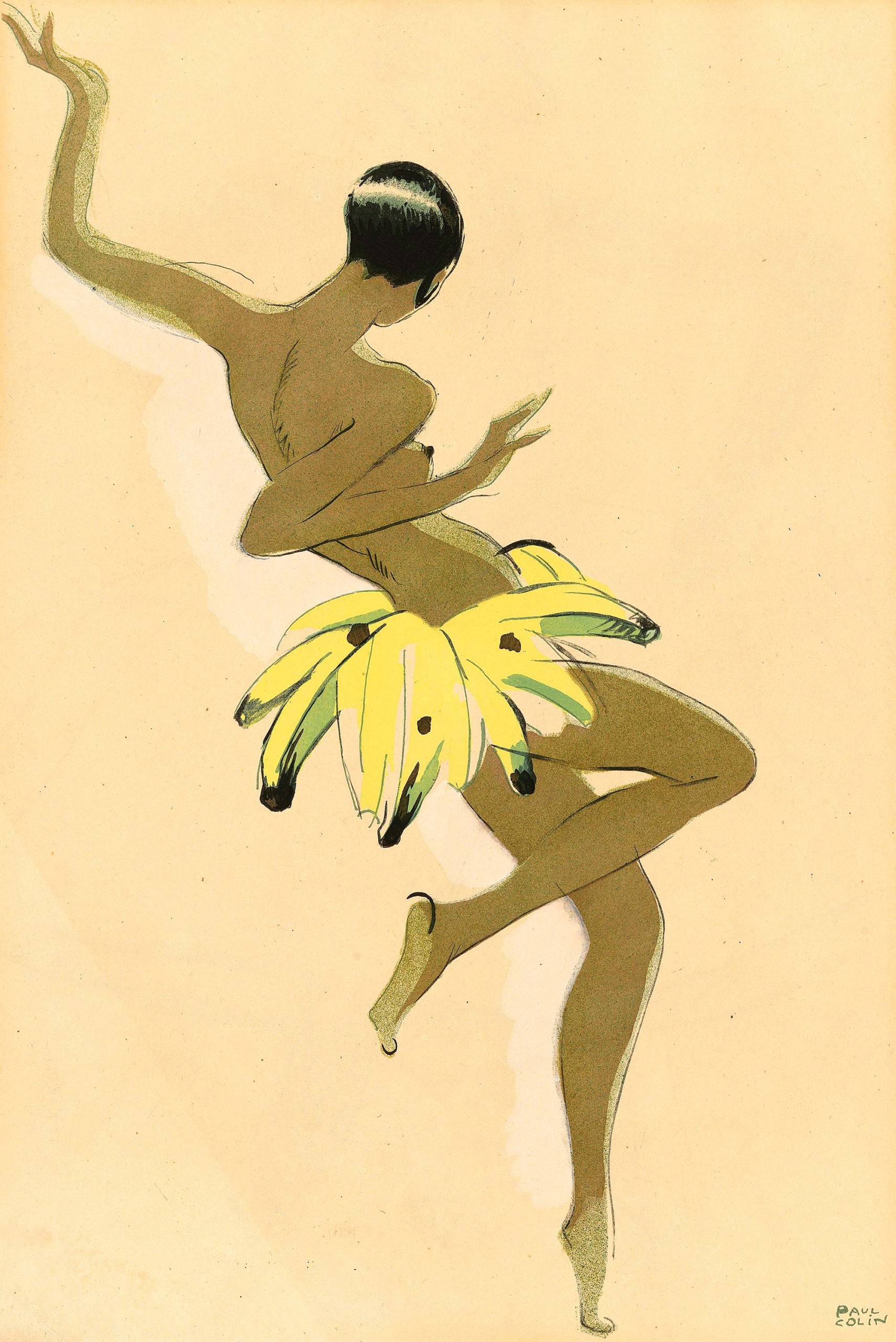

“Josephine Baker” by Paul Colin, 1927, lithograph with pochoir coloring on paper. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Bequest of Jean-Claude Baker ©2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City / ADAGP, Paris.

Once again, those seeking expressive freedom would include the sculptor Augusta Savage, who was free as she would not have been in the United States to visit museums, galleries and exhibitions. Paris “fired the ambitions of Mary Church, Meta Vaux Warrick and Bella de Costa Greene, three women of color and prodigious intellect and talent. Living in Paris liberated Church to “pass,” she said, “as an American”; later she defended negation of color as a form of self-preservation and wrote that she would support it if it helped Black women survive “the capriciousness of American racism.”

Warrick knew that she would need the endorsement of European masters if her art was to be taken seriously, yet despite success and critical acclaim in Paris, she was unable to translate her experience into commissions or sales when she returned home to Philadelphia. Meanwhile, da Costa Green sidestepped the matter of race by presenting herself as a woman of Iberian descent while serving for more than 40 years as J.P. Morgan’s librarian.

Among the other portraits in this heady 60-person assemblage are those of the trailblazing Isadora Duncan and Natalie Clifford Barney, Sylvia Beach, Lois Mailou Jones and Berenice Abbott. We encounter Rose O’Neill’s phenomenally successful Kewpie dolls, which became an important revenue stream for her social activism. Alice Estelle Rice, Frances Cranmer Greenman and Louise Blair Daura were gifted artists known for their experiments with style and the fauvist’s palette. Beach, as the owner and proprietor of Shakespeare & Company, the English language lending library, would jolt the world with its shelves of experimental literature. She became famous for publishing James Joyce’s Ulysses — asserting with confidence that “one day it will be ranked among the classics of English literature.”

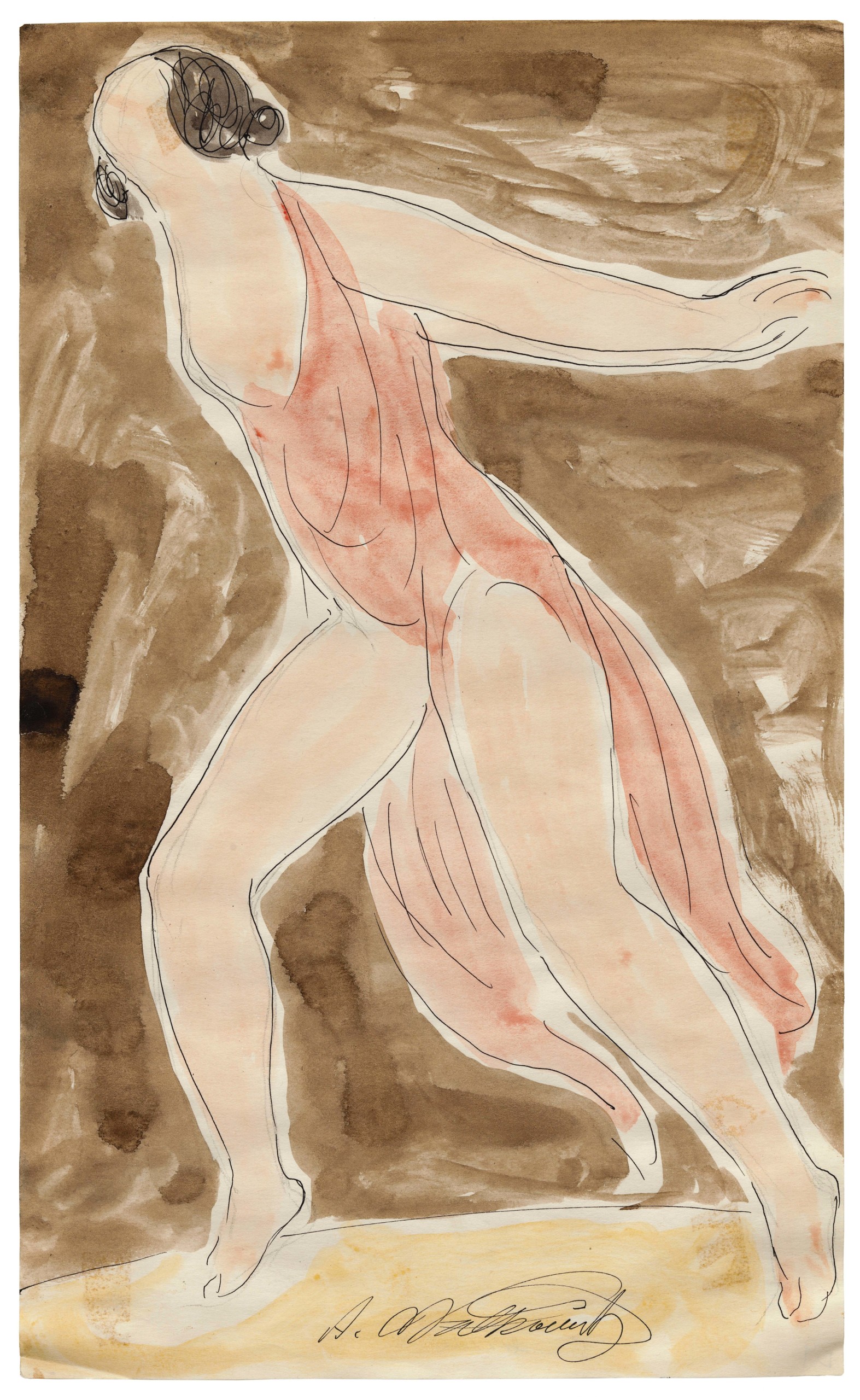

“Isadora Duncan” by Abraham Walkowitz, n.d., ink, watercolor and pencil on paper. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, The Joseph H. Hirshhorn Bequest, 1981. Alex Jamison photo.

Janet Flanner’s Letters from Paris, which ran from 1925 to 1975 in The New Yorker, kept American readers up to date on Parisian art, theater, politics and society. As the magazine’s only foreign correspondent, she wrote under the androgynous pen name of “Genet,” and her ironic and irreverent tone helped define The New Yorker’s style for much of the Twentieth Century.

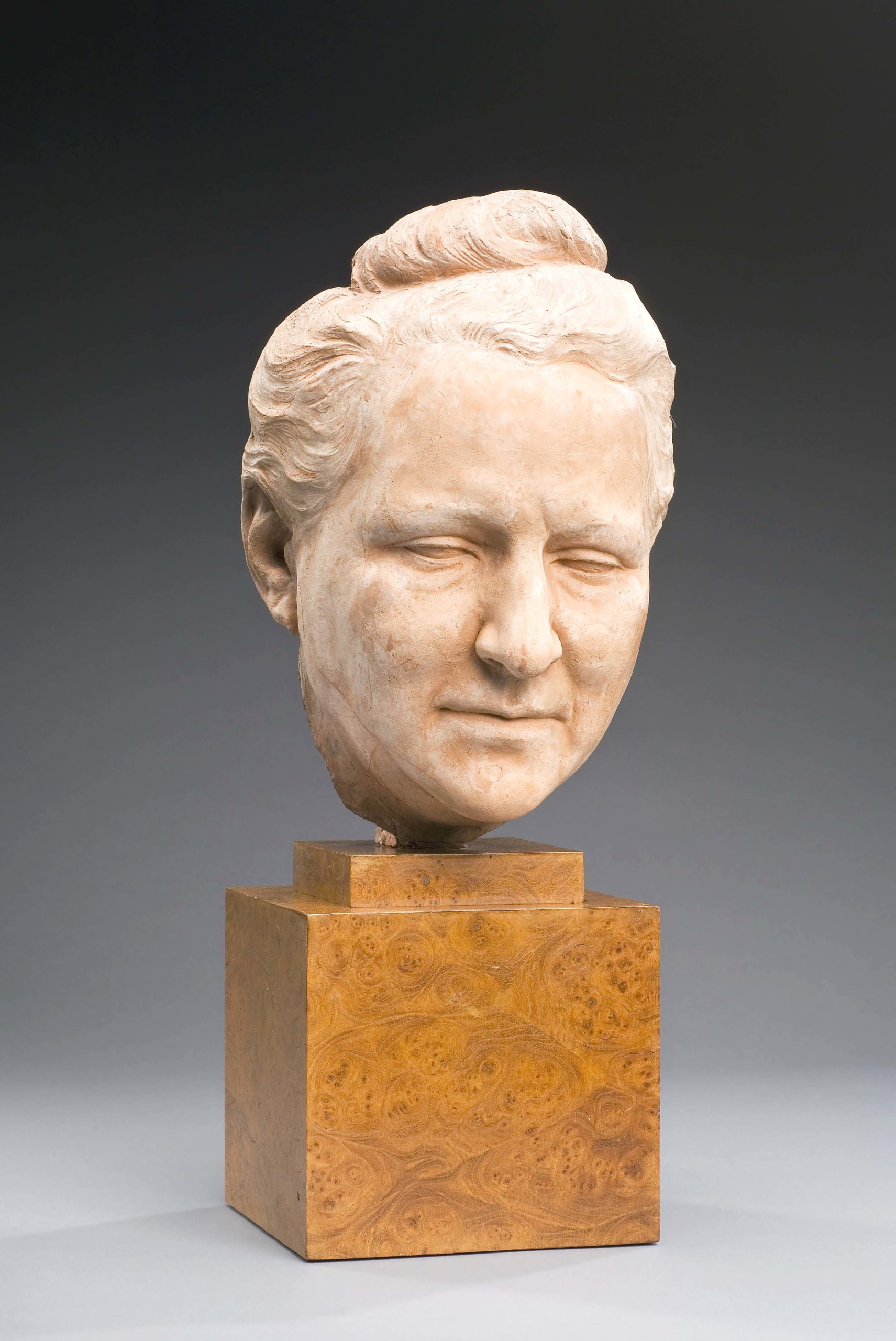

Gertrude Stein had embarked upon a mission to become famous after moving to Paris in 1903, and she did so by assembling an unparalleled collection of avant-garde paintings. Her Latin Quarter atelier did indeed become legendary — and she became one of the most extensively painted, sculpted and photographed writers of the Twentieth Century.

Asleson notes that many of these women “were drawn to influential cultural forums in which same-sex desire was the rule rather than the exception.” Then there was Flanner and her partner Solito Solano’s entanglement with the wealthy British writer and publisher, Nancy Cunard. The three saw themselves as a fixed triangle” of soulmates — and they often appeared in stylish clothes appropriated from the wardrobes of Cunard’s mother.

“Gertrude Stein” by Jo Davidson, 1922-23, terracotta. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Jane Heap, a magazine editor and gallerist, would exert a force in artistic and literary circles, as she expanded her radical magazine’s coverage of emerging art movements. Heap was among women who openly proclaimed their queer identity and who entered into serious same-sex liaisons.

And Ada “Bricktop” Smith, a singer and dancer originally on the Black vaudeville circuit, would gain international renown as the host and owner of some of the most famous and influential nightclubs in interwar Paris. The cultural historian T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting notes that Bricktop, as she was affectionately known, served as both an anchor and a magnet for the expatriate community of African American women, taking the young Josephine Baker under her wing, and welcoming Florence Mills, Nora Holt and many Black performers into the fold. For a number of years her Montmartre nightclubs were go-to stops for those seeking good jazz and to dance the Charleston.

Fast forward a few decades to when the NPG was founded and was charged in 1966 with defining who was historically important and why. “Women were ‘barely part of the equation,’” the NPG director Kim Sajet writes in the catalog with obvious chagrin. Indeed, in the museum’s first exhibition catalog, which featured 164 portraits, 145 were of white men, 10 were of people of color and nine were women.

“Lillian Evanti” by Lois Mailou Jones, 1940, oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Max Robinson. ©The Loïs Mailou Jones Pierre-Noël Trust.

Since then, Sajet said the NPG has made it a mission to “change these dismal statistics” but change “is not only slow but limited by the history of gender discrimination itself,” she said.

“Even today only 11 percent of the works acquired by museums are by women; less than 15 percent of exhibitions are dedicated to their work.”

“The exhibition came to fruition at a time when book banning and controversies over sexual and gender nonconformity roil debate. These present-day concerns are not new. They were pertinent a century ago and help to account for the self-imposed exile of the women in this exhibition,” Asleson writes. Within this context, “Brilliant Exiles” is a long-awaited corrective.

“Brilliant Exiles: American Women in Paris” will be on view at the National Portrait Gallery through February 23. The exhibition will then travel to the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Ky. (March 29-June 22, 2025) and the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia, Athens (July 19-November 2, 2025).

The National Portrait Gallery is at Eighth and G Streets, Northwest. For information, 202-633-8300 or www.npg.si.edu.