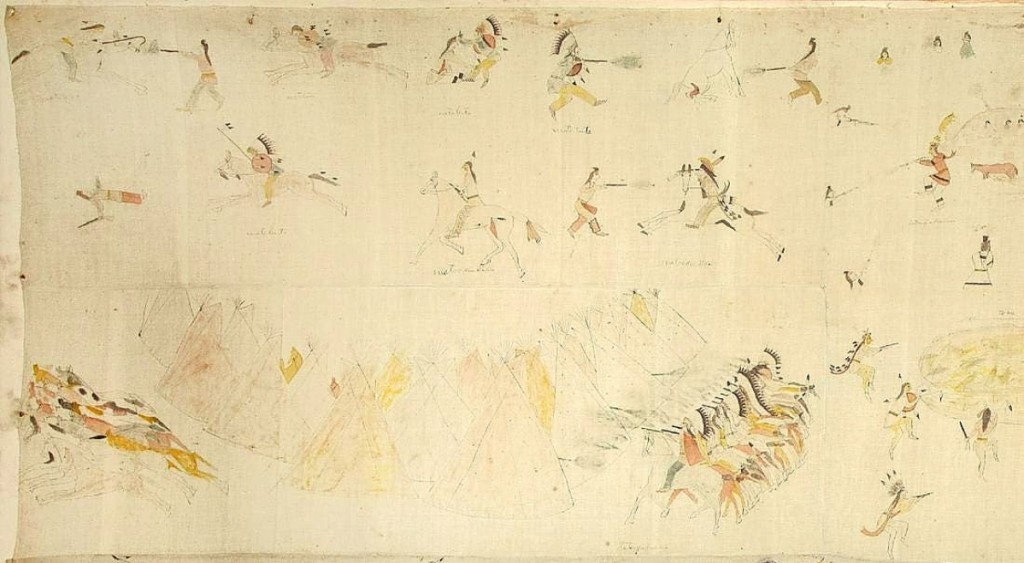

At $90,000, the top lot of the sale was this pictographic painted muslin tipi liner attributed to Mato Luta (Red Bear), a Lakota Hunkpapa. Pictured is a detail of one of the four sections, which stretched ten feet long in total. It was believed to have been created at Fort Yates during the final years of the Sioux-Cheyenne campaign.

Review by Greg Smith, Photos Courtesy Santa Fe Art Auction

SANTA FE, N.M. – Native American art was front and center at Santa Fe Art Auctions through two days of sale February 6-7 as 417 lots crossed the block from contemporary and historic makers. Mediums and forms were wide and far, ranging from works on paper, pueblo pottery, kachinas, basketry and Navajo textiles.

“It was a very strong sale, extremely robust,” said Gillian Blitch, president of the firm on her $750,000 total tally. “The collecting area is very strong, we have new demographics really interested in developing Native American arts. Historic to modern – that’s what the sale demonstrates.”

The sale’s top lot was found for $90,000 in a pictographic painted muslin tipi liner attributed to Mato Luta (Red Bear), a Lakota Hunkpapa. It dated to the late Nineteenth Century, believed to have been completed at Fort Yates during the final years of the Sioux-Cheyenne campaign. Identified by Christina Burke, curator of Native American art at the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, were some of the figures, including the heads-of-households Mato Luta (Red Bear), Mehaka Ciqala (Little Elk), Mato Nape Ska (White Paw Bear) and Kangi Ohitika (Brave Crow). In four sections, the ten-foot-long liner depicted both domestic and battle scenes.

Blitch said she had only seen maybe two of these shaman’s ceremonial guardian implements come to sale in the last few decades. This example measured 21¼ inches high and brought $39,530. Shamans of the Quinault Indians were said to fashion these figures as spirit helpers to assist the shaman at work.

Rising to $39,530 was a shaman’s ceremonial guardian implement, circa 1850, from the Quinault Indians. The carved wood power figure measured 21¼ inches high and appeared as a figure standing atop a handle. In The Box of Daylight: Northwest Coast Indian Art, Bill Holm wrote that these were made to give assistance to a shaman at work, “a representation of a spirit helper of the shaman, said to look just like that spirit experienced by the owner in a trance. The facial painting […] are just as the spirit appeared.” An example of similar form resides in the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection.

Blitch said she had only ever seen two others come to market, this example emerging from a modern art collection featuring alongside works by Picasso and Braque.

Pottery was plentiful, led by a stunner in a 32-rib swirled blackware melon bowl by Santa Clara potter Nancy Youngblood, which brought $9,440. It measured only 8 inches diameter. Youngblood comes from a line of potters before her, including her grandmother, Margaret Tafoya, and those after her, extending to her three sons. Her swirled works were inspired by her great uncle, Camilio Tafoya, a noted pueblo potter. Behind that were a number of late Nineteenth or early Twentieth Century jars. An Acoma example measuring 13 inches high went out at $8,260, a Zia water jar measuring 10½ inches high brought $6,490, another Zia example took $5,664, and an Acoma black on white wedding jar went out at $5,428.

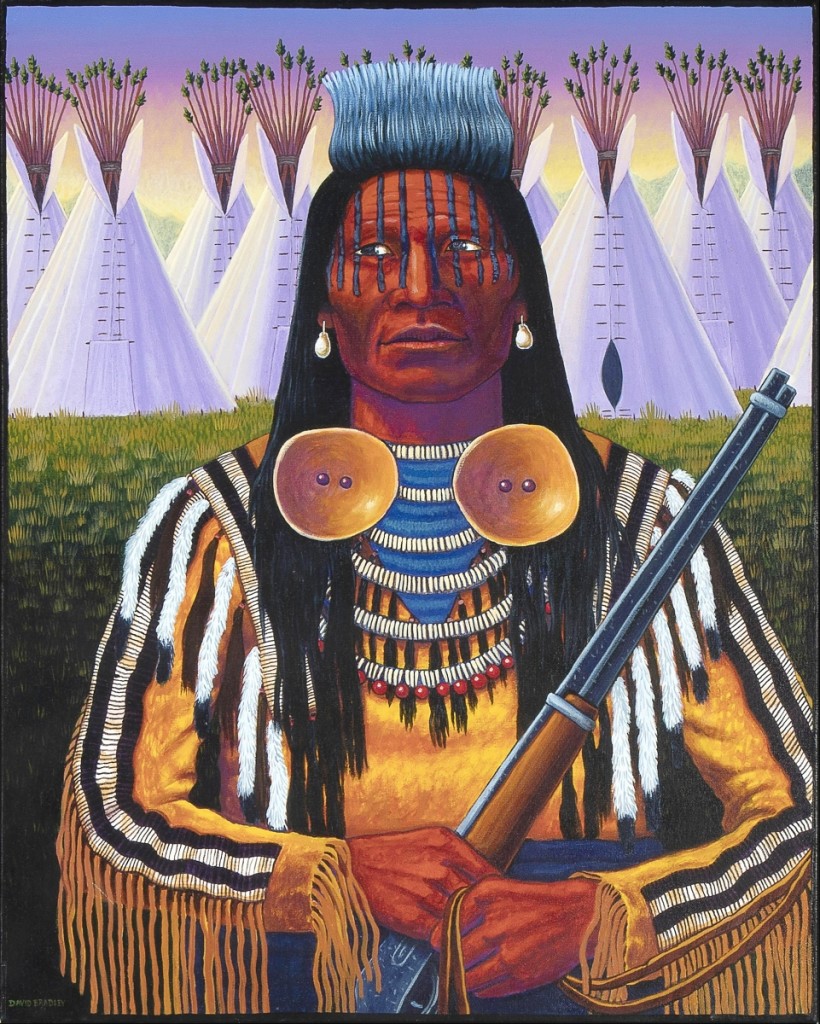

“Crow Warrior” by David Bradley (Chippewa, b 1954), acrylic on canvas, 30 by 24 inches, 1994, $11,800.

Twentieth Century Kachina dolls found competitive bidding, including $6,490 paid for two Zuni Kokosori, or “Little Fire God,” examples that dated to circa 1950. One of the figures retained its original trading post label to the underside, which read “Zuni / Fire God / Cholawitze / 29.” One figure in brown featured multicolor spots while the figure in black featured white spots only. Both had cloth around their waists and the same braided rope and feather to the top. Dating to 1920 was a Hopi wolf kachina in cottonwood that brought $5,664. It too had the trading post label that identified it by name as Kweo. Notes in both of the lot descriptions related that these were sold to benefit a New Mexican Native American museum.

Other dolls, including Tesuque Rain Gods and Mojave examples, came from the personal collection of dealer Mark Blackburn. Two fired clay Tesuque rain gods, circa 1880, went out at $2,242. “Tesuque Rain Gods have always appealed to me, even though they were made for the burgeoning tourist market beginning in the 1880s,” Blackburn wrote. A pair of male and female painted clay Mojave dolls with black and white glass seed bead necklaces and earrings went out at $1,770.

Most notable from the Blackburn collection was a group of five Hopi clay figures, circa 1880, that brought $8,260. They were offered alongside a copy of the Report on Indians Taxed and Not Taxed in the United States (Except Alaska) at the Eleventh Census 1890, where two figures were illustrated, as well as two copies of the 1892 title The Song of the Ancient People. The figures had been collected prior to 1890 by artist Julian Scott, who traveled west and worked on the census.

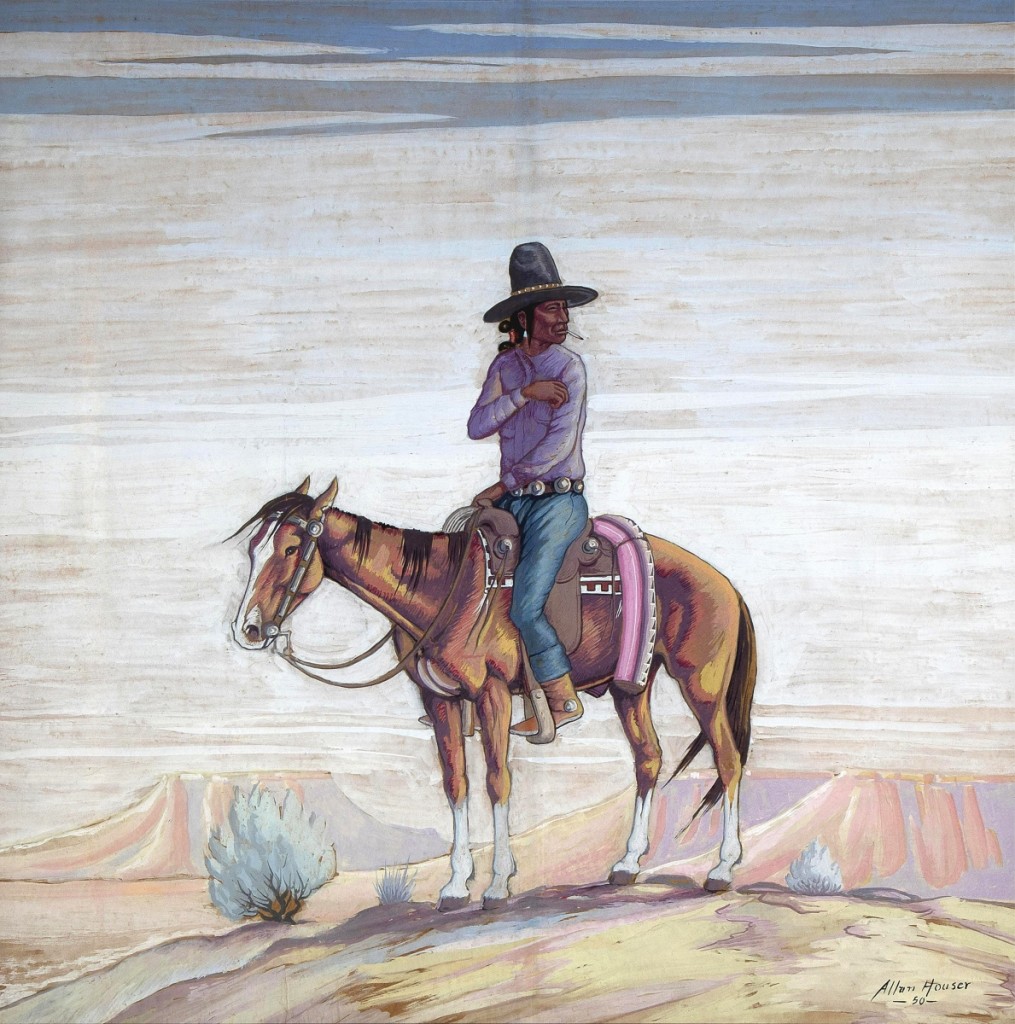

Blitch said “Indian Rider” by Allan Houser was among the largest two-dimensional works by the artist the auction house had ever handled. The mixed media measured 42 by 42 inches and came from the collection of artist Tony Abeyta. Both artists had connections to the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. The work went out at $10,620.

Textiles were led by a Navajo pictorial double saddle blanket, circa 1960, that sold for $5,664. It featured a band of three horse heads across its middle and a cow on each side. Taking $5,412 was a Navajo Germantown third phase chief’s blanket, circa 1890, that measured 68 by 51½ inches.

Selling for $4,956 to a collector was an area textile in gray and black on a cream ground, that was accompanied by a note from the A. Arnold Trading Post. In the note dated 1912, Arnold writes that the blanket he sent “was woven by the Wife of Old Manuelito the last War Chief of the Navajo Tribe, who happens to be a personal friend of mine. This is the Chief that was called to Washington D.C. during Grants administration regarding the western Indians.” Chief Manuelito’s wife’s name was Juanita Asdzáá Tl’ógí, or “Weaver Woman,” and she accompanied her husband on those delegations. In 1868, Manuelito was among the 29 Native American signers of the Treaty of Bosque Redonodo, which ended the Long Walk – a forced relocation – and established a sovereign Navajo reservation in New Mexico and Arizona.

“There was no border on it and it was so tightly woven, but most striking was its simple, modern design,” Blitch said. “She went very much for more muted colors. It was all about simplicity. It’s very rare to come across anything that you can trace the provenance to her.”

Leading fine art was David Bradley’s (Chippewa, born 1954) “Crow Warrior,” a 30-by-24-inch acrylic on canvas done in 1994. It sold for $11,800. Also from Bradley was “Ghost Dance Revelations: Resurrection #3,” a 1996 mixed media on canvas measuring 40 by 30 inches and seemingly depicting the auras of spirits rising from a group of tipis. That brought $6,490. Bradley received a traveling retrospective in 2015 that began at Santa Fe’s Museum of Indian Arts & Culture and concluded in 2019 at the Autry Museum of American West. Dan Namingha’s (Hopi-Tewa, b 1950) “Pahlik Mana (Butterfly Girl), a 60-by-48-inch acrylic on canvas, sold for $4,720.

Nancy Youngblood, a descendent of the Tafoya family of potters, produced this rib-swirled melon bowl that sold for $9,440. An 8-inch diameter.

Work from deceased artists found competition as Allan Houser’s (Chiricahua Apache, 1914-1994) “Indian Rider” took $10,620. The 1950 work had at one point been handled by Santa Fe’s Zaplin Lampert Gallery and was in the collection of Navajo artist Tony Abeyta, whose auction record was set in November at Santa Fe Art Auction. “We think that’s the largest two-dimensional Houser work we’ve ever come across,” Blitch said. Houser’s “Indian Rider” was created during a two-year period that the artist was living on a Guggenheim Fellowship. A ledger drawing by Tsaitkopeta [Bear Mountain] (Kiowa, 1852-1910), went on to bring well above estimate at $7,670. In ink on paper, the circa 1875 work featured two Native Americans on a hunt with spears chasing a bull. It was featured in the 1971 book by K. Daniels Perterson, Plains Indian Art From Fort Marion.

In beaded works was a $4,720 result for a Lakota/Sioux pictorial beaded pipe bag, circa 1880-90. It featured images of American flags, tipis, the word “PuP,” and a miniature strike-a-lite bag with images of pipes. A pair of Arapaho beaded tipi bags from the Nineteenth Century went on to bring $4,720, while an Arapaho beaded dispatch case took $4,484.

“It was thrilling to have such a broad array of native arts – we had everything in there,” Blitch said. “Interest was global, some things selling to Paris and others across the country.”

All prices include buyer’s premium. The firm’s next Native American art sale will take place in August. For more information, www.santafeartauction.com or 505-954-5858.