-1024x469.jpg)

The “Natural Beauties” installation includes a showcase of deep blue lapis lazuli objects, including a Parisian potpourri vase, 1770s, and Viennese horn adorned with silver, enamel and pearls. On the shelf at upper right, the center covered vase was made in Paris during the 1780s from dark red porphyry.

By Karla Klein Albertson

WASHINGTON, DC – Long before empresses wore faceted diamonds and emeralds, deeply colored semiprecious stones were the bling du jour. The gleaming golden collars worn by the Egyptian pharaohs were inlaid with bits of deep blue lapis lazuli, and Roman emperors wore seal rings of agate and carnelian. Sculpture of jade ornamented palaces of the Orient, and imperial courts from England to Russia commissioned decorative objects made from every sort of hard stone available on the trade routes of the day.

Marjorie Merriweather Post (1887-1973), the memorable heiress and avid gatherer of beautiful things, who turned her Washington mansion into the Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens, was frankly smitten with these beautiful materials. No surprise then that “Natural Beauties: Exquisite Works of Minerals and Gems” should be the subject of an exhibition, which has been extended to January 3. The show brings together more than a hundred objects in the dacha galleries on the estate grounds. Most are from the museum’s extensive permanent collections but also featured are some interesting loans that round out the history of pietra dura artifacts in world art.

Writing about the exhibition, executive director Kate Markert stated, “Marjorie Post was a renowned collector, known for her keen eye and love of beautiful and finely crafted objects. Her passion for hardstone developed at a young age and continued throughout her life, culminating in this unique assembly of treasures from around the world.”

In one section of the galleries, the exhibition has gathered objects from Marjorie Merriweather Post’s stunning “Malachite Room,” a display filled with decorative pieces carved in Russia from the vivid green stone mined in the Urals — at center, a Saint Petersburg clock made circa 1876 and a tall Russian tazza from the 1830s.

The only child of cereal magnate C.W. Post, she began collecting French furniture and decorative arts during her marriage to financier Edward F. Hutton. A later marriage to Joseph E. Davies, who was ambassador to Russia during the turbulent 1930s, brought Post in contact with Russian art at a time when many pieces were being sold for cash on the international market. Hillwood today is perhaps best known for its holdings of works by Carl Faberge, which were made for the Russian royal family, including two of the sought-after Imperial Easter eggs.

Thus, chief curator Dr Wilfried Zeisler, a graduate of the Sorbonne and the Ecole du Louvre in Paris who came to the museum in 2014, had a deep inventory to call upon when he began organizing “Natural Beauties.” In a conversation with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, he noted that Mrs Post’s interest in hard stones is demonstrated in many aspects of her collecting: “We were looking at our Faberge collection, and it was obvious that many objects that she collected were specifically made of hard stone or included them in the decoration. So, I knew that it was a wonderful topic for an exhibition as we have over 400 objects in the category of hard stone. And they’re not only Russian, although that group is a large part of the exhibition. A few of them are on view for the first time in this exhibition.”

When visitors tour the galleries, they find a show divided into sections such as “Fancy Seals” or “Animals and Figurines” but also separated into distinct materials such as agate or jade. There is undeniably a geological aspect to the exhibition. Zeisler pointed out, “The oldest exhibit we have is a piece of petrified wood. That’s how we start the exhibition because it was actually collected by Post’s father, who was the founder of the company and a collector himself.” Furthermore, there are loans of mineral samples from the National Museum of Natural History. In a display devoted to vivid blue lapis lazuli is a hunk of Lazurite from Badakhshan, Afghanistan, an ancient source of the mineral. At the same time, a nearby vase reveals the transformation the material undergoes in the hands of an artist.

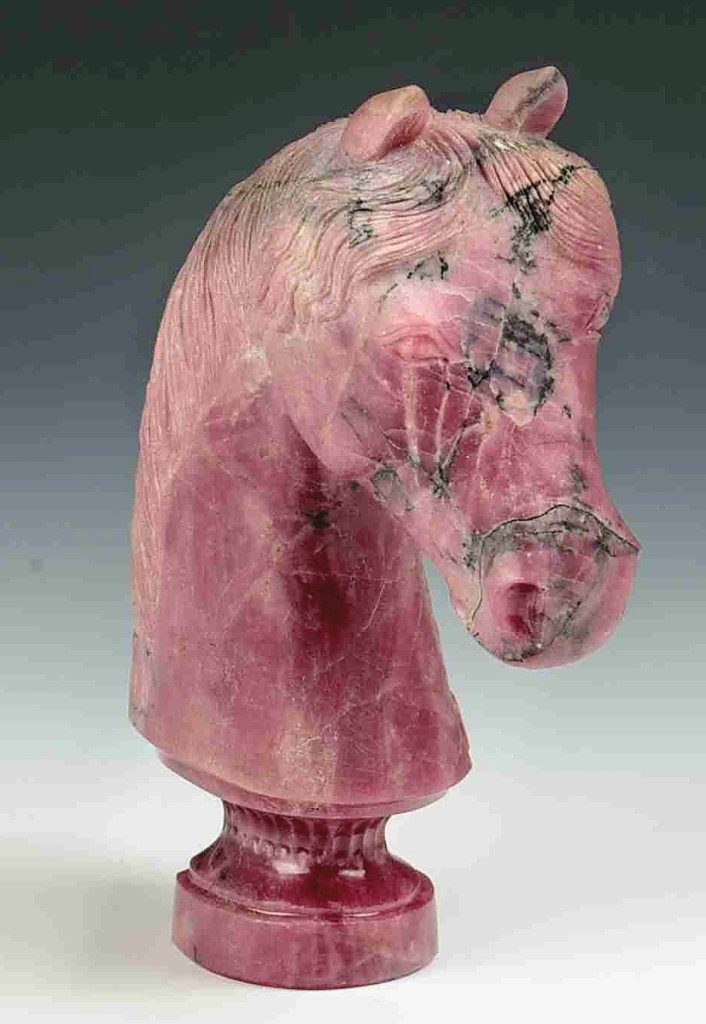

Seal, Russia, Nineteenth Century. Rhodonite. Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens. Photographed by Brian Searby.

Another selection of objects focuses on the beauty of brilliant green malachite, once extensively mined in the Russian Urals in such quantity that an entire table could be assembled with carved elements of the mineral. On the hunt, art historians can find malachite art works around the globe, from ancient Egypt to the early civilizations of Mexico to the churches of Renaissance Rome. Post once had an entire “Green Room” to show off her collection of malachite objects.

Zeisler is delighted to point out some of his favorite pieces, such as the large collection of desk seals – an essential proof of identity in the history of written documents. The diminutive objects, many only 3 or 4 inches in height, were turned into miniature sculptures. There are a number of seals with portrait busts, including a rock crystal example with Russian Empress Catherine the Great and a smoky quartz bust of poet Alexander Pushkin.

The curator also pointed out exhibits connected to the Yusupov family, which amassed great wealth under the Russian tsars and became known for a superb art collection. Of course, that all ended with the Revolution. Like much of the country’s nobility, Felix Yusupov, the last Prince, left Russia for Paris in 1919, taking with him Rembrandt paintings, jewelry and decorative arts made from hard stone. During the 1920s – like many displaced aristocrats – the family sold off many of their treasures to keep afloat financially.

Figurine of a French bulldog, Russia, circa 1900. Agate, gold, emeralds. Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens.

In 1927, Marjorie Merriweather Post purchased her first Faberge piece, which happened to be a box of amethyst quartz with a carved lion of red translucent spinel on top from the Yusupovs’ collection. In the show, Zeisler was pleased to reunite this box with another object from the same family, which is on loan from a New York source. This is a female Buddhist deity, also of spinel, which had been carved in China in the 1400s, then decoratively mounted at Cartier New York around 1925 with rubies, gold, jade and glass.

Zeisler explained that the figure had never been exhibited before: “The Yusupovs fled the Russian Revolution with family heirlooms, some of which were sold abroad. We have a box from the same collection, and the two pieces are back together for the first time since the 1920s in this show. I was very happy to find the figure because Prince Yusupov mentions it in his memoir. We knew that it has been sold in the United States, but it had never been shown in an exhibition with another piece that had belonged to the same family.”

Post’s other home, the intriguing Mar-a-Lago mansion at the tip of Palm Beach island, has been in the news in recent years, although it is now used as the focal point of a private club with dining, golf and beach facilities. Such was the heiress’ fascination with hard stones, that – like connoisseurs of the past – she commissioned for the residence a magnificent dining table inlaid with a mosaic of hard stones, including marble, lapis lazuli and chalcedony. Joseph Urban was the designer, and it was manufactured in Florence in 1928 by the Societa Civile Arte del Mosaico. The table was transferred to Hillwood after her death and now occupies the formal dining room; the intricate pattern of the multi-leaf table can be seen on an example in the exhibition.

Table, Societa Civile Arte del Mosaico, manufacturer, Joseph Urban, designer, Florence, Italy, 1928. Wood, marble, lapis lazuli, jasper, alabaster, chalcedony, shell, gabbro. Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens. Photographed by Edward Owen.

In conclusion, Wilfried Zeisler wrote of the exhibition: “‘Natural Beauties’ will display hardstone as it has not been seen before, offering an exploration into not only the materials themselves and how they were transformed but also the resulting lapidary marvels that speak to the cultures in which they were made.”

Hillwood is at 4155 Linnean Avenue in a quiet residential neighborhood in northwest Washington, DC. The estate is currently open to guests with reservations which can be made at www.hillwoodmuseum.org or by calling 202-686-5807.

.jpg)