WILLIAMSBURG, VA. — How were buildings constructed in the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Centuries in Virginia? What did the builders use? What can the collecting habits of 85 generations of rats reveal?

Wetherburn’s Tavern intact section of shingles courses, circa 1740, cypress, removed from under a circa 1785 shed roof addition on the tavern. All photos courtesy of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Valuable clues and answers can be found in the architectural objects and fragments from both surviving and demolished buildings and will be revealed in “Architectural Clues to Eighteenth Century Williamsburg,” which opens May 28 and will remain on view indefinitely at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, one of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

The exhibition will explore objects in the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s architectural collection illuminating seldom-seen details and information used to inform work in the Historic Area from the 1930s to present day. “Architectural Clues” not only will enhance visitors of all ages’ exploration of Colonial Williamsburg’s historic area, but also architecture aficionados’ understanding of period construction outside the area. These fragments can inform how architectural preservationists know what they know and how to do what they do.

This pine window sash, circa 1750s, informed the window design and paint colors seen at the reconstructed Charlton’s Coffeehouse.

“Like antiques and works of art, early buildings retain abundant information about past cultures,” said Ronald L. Hurst, the foundation’s chief curator and vice president for collections, conservation and museums. “When properly studied, they speak to us about everything from historic trade practices to social hierarchies. As the steward for scores of historic structures and thousands of architectural fragments, Colonial Williamsburg is an excellent laboratory for such inquiries. At the same time, regular advances in methods of scientific inquiry now allow us to learn from these materials in ways that were unimagined even ten years ago. This exhibition will provide a window into this fascinating subject.”

The earliest objects in the exhibition are the circa 1715 finial and weathervane rod from Colonial Williamsburg’s Magazine. Constructed in 1715 as storage for the arms and ammunition dispatched from London for the defense of the colony, these objects were removed from the building after the roof caught fire in 1898.

Wetherburn’s Tavern (one of the most successful and popular taverns in Williamsburg in the 1750s) provided a wealth of architectural treasures that will be featured, including Eighteenth Century shingle courses. Roof elements such as these help to inform shingle sizes and roof design throughout the Historic Area. The tavern also revealed Eighteenth Century window elements, including a sash, sash weights and pulleys.

Perhaps the most amusing finds are the generational nests that 85 generations of rats over 127 years made as their homes in Wetherburn’s Tavern. The nests revealed quite a snapshot of life within a 300-foot-diameter space; the cache of treasures included fragments of documents, pieces of furniture, ceramics, a corn cob, textiles, shoes, silver utensils and much more.

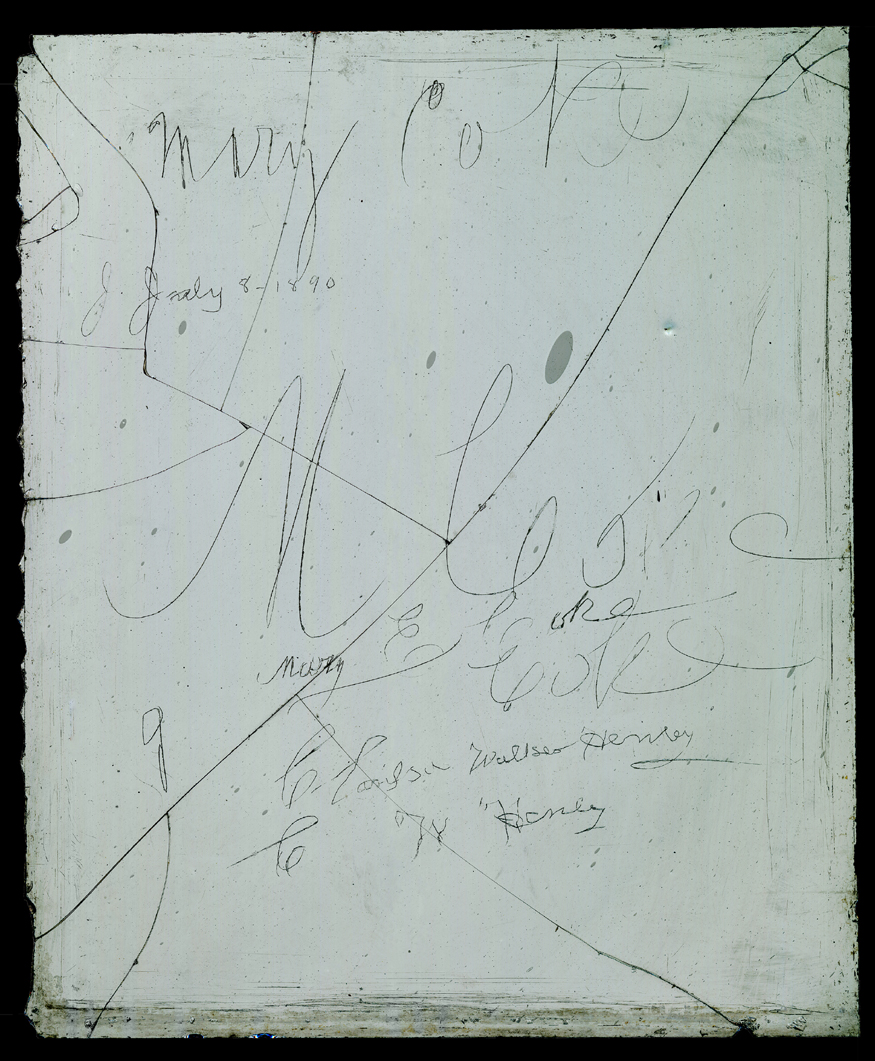

It is believed that two female cousins etched their names in a glass pane (originally installed circa 1753) at Bassett Hall during the time the Coke family lived here from 1843 to 1845. Mary E. Coke would have been about 15 and Clarissa W. Henley about 19.

“All of the objects and fragments collected throughout the Historic Area give us important insight into Eighteenth Century architectural design and are instrumental in informing the work there,” said Matt Webster, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s director of the Grainger Department of Architectural Preservation. “These are just a few pieces from our collection of over 15,000 architectural fragments, and they represent a very important research tool for the foundation and outside scholars,” said Webster’s exhibition co-curator Dani Jaworski, associate curator of architectural collections.

Another important piece in the exhibition is the Bruton Parish Church pilaster and capital, which are believed to have been carved in England. This piece and some of the other fragments removed from the church during the 1905–07 restoration were kept by a local resident. During restoration work in the 1920s, the fragments were found in the cellar of a building on the Raleigh Tavern property and served as models for the paneling, capitals and large round window seen today in the church.

Etched window panes showing hidden and rarely seen construction details; stair posts, rails and balusters showing the hierarchy of Eighteenth Century architectural designs; a variety of interior decorative treatments, including an ornate pilaster and cap section, a faux-marble painted mopboard and a stone paver with a mason’s mark from the Governor’s Palace (the home to seven royal governors, Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson) are also among the highlights of Architectural Clues.

Bricks also tell an intriguing story in the exhibition. A view of glazing strips in one brick indicates the size of the gaps between stacked bricks that allowed heat to rise in the kiln when they were made. The glazed line also informs what happened during the final stages of brick making. In another example, a “dimpled” look appears as a result of the brick having been briefly rained on during the drying process. Proof that the bricks were handmade can be seen in a third example that has a fingerprint in it where the maker picked it up when it was still wet.

Designed with function in mind (to protect the base of the wall), this baseboard/mop board made of yellow pine, dating to the third quarter of the Eighteenth Century, was decorated with faux marbling. The piece is in the Taliaferro-Cole House. The intent was not to portray stone exactly, but instead to show the wealth and status of an owner that could afford to have such work done.

In the Eighteenth Century, color told a story. The exhibition will examine how Colonial Williamsburg’s approach to paint analysis from the 1930s to its use of modern analytical equipment today has helped conservators understand the use of different paints and colors. “Architectural Clues” will uncover the process of developing an accurate view of the materials and true colors used in the Eighteenth Century, which helps inform the streetscape seen today in the Historic Area.

The exhibition will be of keen interest to families and history fans, architectural and design scholars and anyone interested in a greater understanding of how buildings were constructed in the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Centuries.

The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg are at the intersection of Francis and South Henry Streets. For more information, www.colonialwilliamsburg.com or 757-220-7724