“Large Turquoise Urchin Basket” by Jeremy Frey (Passamaquoddy, b 1978, Indian Township, Maine), 2019, brown ash and sweetgrass, overall: 5¼ by 11½ inches diameter. Museum purchase through the Kenneth R. Trapp Acquisition Fund.

By James D. Balestrieri

WASHINGTON DC – Craft has come into its own. At a moment when the word “craft” is everywhere – think “craft beer” – you might think that craft would be relegated to the position of art’s poorer cousin, as it has in the past. Where “artisan” sidles up to “art,” craft, as demonstrated in “This Present Moment: Crafting A Better World,” now on view at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, blurs and smashes any remaining boundaries with art, even as it asserts its own identity.

It wasn’t that long ago that craft could be defined – generally by non-craftspeople – as utility of form expressed through exceptional skill. There’s always been a sort of Taoist condescension towards craft, a “Truly the great cutter does not cut” attitude that single-minded repetition and a oneness with the tools of the trade are the hallmarks of craft, as opposed to the flashes of inspiration and lofty aspirations that mark the true artist. Take one quick look at a great piece of stained glass, however, and this false dichotomy breaks down in a hurry.

Many of the objects in “This Present Moment” play with utility, repudiate utility entirely or repurpose utility into unique, one-of-a-kind works of art that unite beauty with activism. Meaning is their utility. And, after all, craft throughout the ages – baskets, furniture, textiles, pottery, glass – to name five forms, has sprung in large measure from the work of women, people of color and the laboring class. The evolution of these, and many other forms, from the artisanal to the artistic, is only natural in a world as beset by division as “this present moment” is.

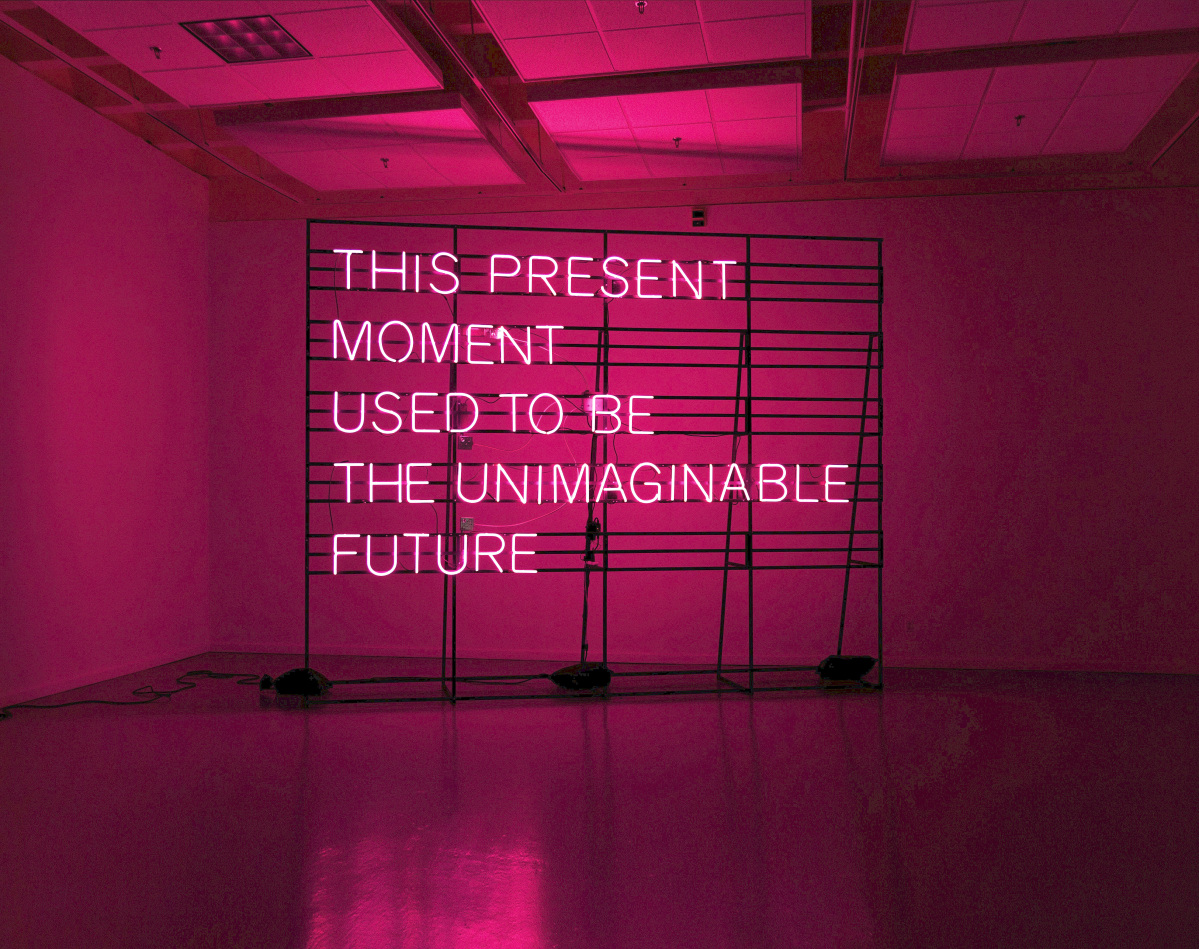

“This Present Moment” by Alicia Eggert (b 1981, Camden, N.J.), 2019-20, neon, custom controller and steel; neon produced by Amy Enlow, fabrication assistance by Teresa Larrabee, Paolo Tamez-Buccino, Jaelyn Kotzur and James Akers, 144 by 180 by 48 inches. Museum purchase through the Renwick General Acquisitions Fund.

Brilliantly, the curators organize the exhibition around a quote from Victor Hugo’s 1831 novel, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, as seen through the lens of philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s seminal work, The Poetics of Space. Hugo wrote, speaking of the titular character: “In the course of time there had been formed a certain peculiarly intimate bond which united the ringer to the church… Notre-Dame had been to him successively, as he grew up and developed, the egg, the nest, the house, the country, the universe.” In her catalog essay, “This Present Moment,” Lloyd Herman curator of Craft at the Renwick, Mary Savig, quotes Bachelard and extends the metaphor to the ways in which we craft and transform our homes: “‘For our house is our corner of the world. As has often been said, it is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word,’ Bachelard asserts. The basic architecture of a house provides a sense of stability and security. Over time, a shelter becomes integral to one’s own conception of self.”

Craft is tethered, even when the tether is tenuous, to memory, to the senses, and to experience – and “home” is a locus of these. Art seems to operate, and oscillate, between the decorative and the disruptive. At the risk of being reductive, craft seems to spring from, and to affect, the deep self, where art vivifies aspects of what I might call the not-self.

Yet this opposition, as I look through the works in “This Present Moment,” isn’t hard and fast.

Taking, as a starting point, the five themes of the exhibition: egg, nest, house, country, universe, I find that the works resist even these themes, fitting quite neatly into more than one – or all of them – or falling in between. I want Cindy Drozda’s (American, b 1958) “Pele (Hawaiian Goddess of Fire)” beautifully symmetrical, precariously perched, burl and blackwood sculpture to serve as my “egg” example, simply because of the ovoid shape and sensation that the egg aspect of “home” is fragile. The pattern of the grain on the burl, however, on that ovoid shape, and the story of the goddess Pele, who created volcanoes, fire and the Hawaiian Islands, suggests elemental, universal forces and images of the cosmic microwave background. Egg is universe; universe is egg. Both are home.

“Drag” by Susie Ganch (b 1971, Appleton, Wisc.), 2012-13, collected detritus and steel, 32 by 32 by 132 inches. Gift of the James Renwick Alliance in honor of Robyn Kennedy.

It’s natural to associate woven works, especially baskets, with nests. Yet the more you take in Polly Adams Sutton’s (American, b 1950) sprawling, chaotic “Facing the Unexpected,” where chaos is mathematical – that is, an order of determined indeterminacy that appears chaotic at certain scale – the more it assumes the shape of neighborhood or nationhood in my mind. The forms pull and push and twist, as if striving to break free of the structure that created and sustains them.

Set aside the overt politics of Gail Tremblay’s (American, b 1945) “When Will the Red Leader Overshadow Images of the 19th-Century Noble Savage in Hollywood Films that Some Think Are Sympathetic to American Indians,” woven from 35mm film from the 1981 film Windwalker. View it on its own terms. What does film weave if not the myths of national identity? What might this basket – this porous egg – house? Preconceptions? Stereotypes? Myths to live by? Myths to die by? Or, perhaps, an emptiness, a potential, a possibility?

Move from nest to house. Margarita Cabrera’s (Mexican, b 1973) works reconceive small household appliances – coffee maker, toaster, blender: things we rely on that make a house a home – in vinyl, thread and wire. They seem like post-modern purses or the kinds of opportunistic items that city birds transform into nests. The threads dangling from them support this interpretation. In vinyl, with their function removed, we notice them, these machines that wait, silent and all but invisible in our homes until we need them. Ever wake to find the coffee maker broken? By imparting a coziness to the shapes of these mechanical appliances, Cabrera reminds us of their importance and restores their essential nest-ness.

“Run, Jane, Run!” by Consuelo Jiménez Underwood (b 1949, Sacramento, Calif.), 2004, tapestry-woven cotton, linen and other fabric with barbed wire and caution tape, overall: 120 by 67-5/8 inches. Gift of the Alturas Foundation.

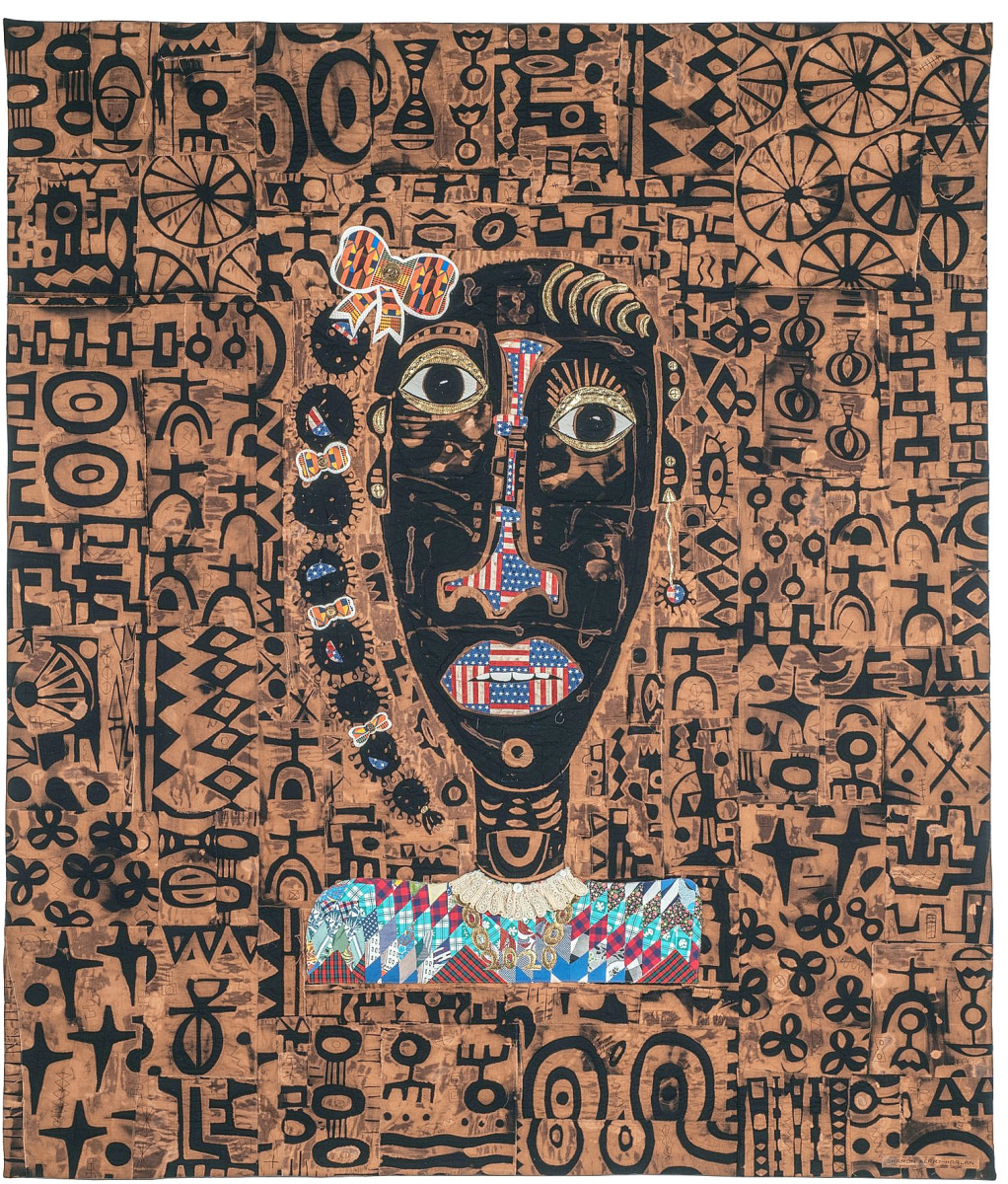

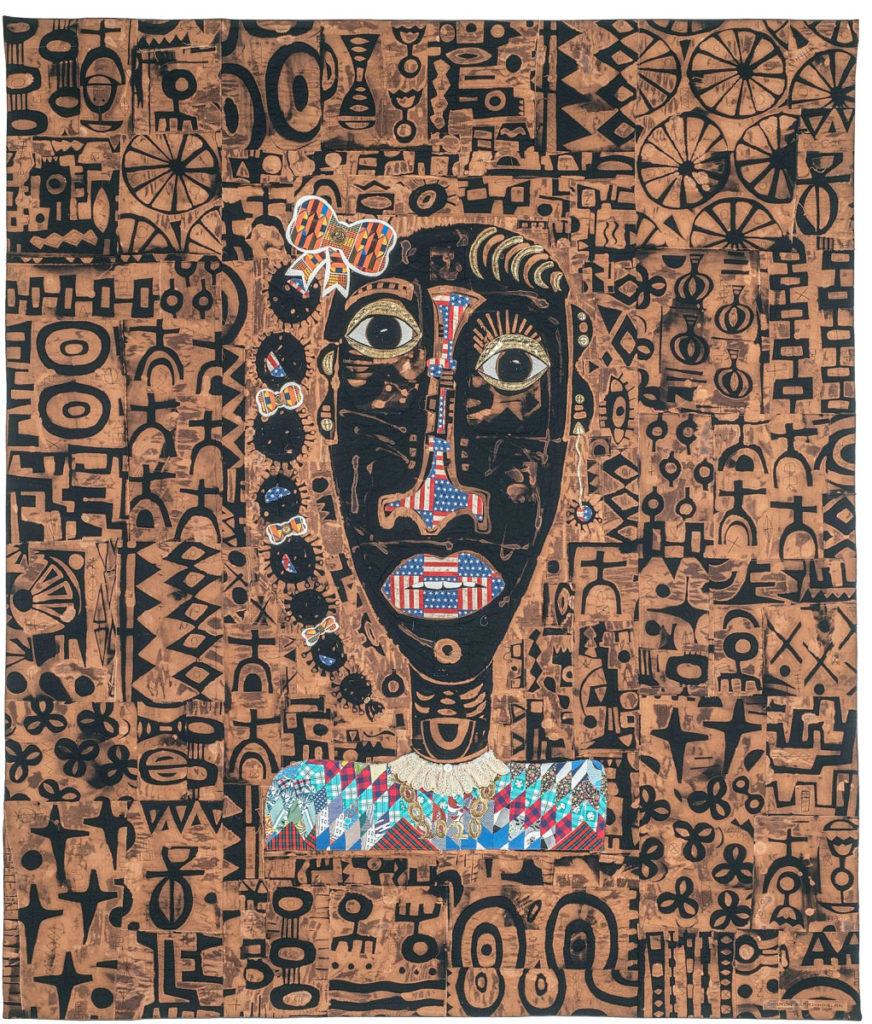

Countries are messes with edges and flags. Spread a quilt on a bed, and it becomes what Robert Louis Stevenson called “the land of counterpane,” a world – a universe – where anything can happen. Hang that same quilt on a wall, release it from its function, and it can become a personal and familial flag, a statement of endurance and tradition. Sharon Kerry-Harlan’s (American, b 1951) “Portrait of Resilience,” as Mary Savig writes, “depicts a girl with a youthful bubble braid. Each bubble is haloed with the crownlike appearance of a SARS-CoV-2 virus particle. The girl’s blouse is constructed of an antique patchwork quilt, adorned with a 2020 golden necklace made with faux leather. Her lips and nose are made of a commercial cotton American flag, and the bows accenting her braid are made of kente cloth. With these materials and symbols representing past and present Black and American culture, this portrait is a window into the experience of a Black American woman during this current moment.” (cat. pp. 43-44) Given the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on communities of color, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the ongoing racial reckoning, the quilt becomes a banner in which the pieces of an American flag that compose the woman’s nose and mouth seem to ask, “How American does she feel?”

Consuelo Jiménez Underwood’s (American, b 1949) textile, “Run, Jane, Run!,” transforms an actual “Immigrant Crossing” sign from the San Diego area into textile art. The equation on the sign between immigrants and, say, deer – or moose, or geese or turtles – is rendered with a shocking luminosity as Underwood severs the image from the category of “road sign” and weaves it into a fabric – the fabric – of the nation. Telling motorists to watch out for people, families on the run, in search of a better home, curves the theme of nation back on itself. Home, a place and idea that we might take for granted, isn’t guaranteed.

There isn’t an object in “This Present Moment: Crafting A Better World” that isn’t, ultimately, a unique universe. The neon piece that gives the exhibition its title, Alicia Eggert’s (American, b 1981) “This Present Moment,” alternates between “This Moment Used To Be The Future,” and “This Present Moment Used To Be The Unimaginable Future.” It’s the qualifier “Unimaginable,” without a moral or ethical component – after all, “Unimaginable” might be good or bad – that connects the statement to our own moment-by-moment lives as well as to the expansion of the universe from its origins. Susie Ganch’s (American, b 1970) “Drag” makes human refuse into a giant chain that then becomes a train that trails behind humanity. The effect suggests that we are wed to the Earth we make, our home in the universe, an Earth – and home – that we are capable of destroying, and that is capable of destroying us. At first glance, and to you, perhaps, Connie Mississippi’s (American, b 1941) “Midnight Mountain” doesn’t readily evoke universe. But to me, the undulant form, inviting tactility, speaks to untapped energies. It’s an object for further study from an as yet unwritten, and possibly unwritable, poem.

“Portrait of Resilience” from the “Flag Series” by Sharon Kerry-Harlan (b 1951, Miami, Fla.), 2020., machine-quilted, dye-discharge fabric designed by the artist and antique quilt, vinyl, American flag and African print fabrics, 86½ by 73½ inches. Museum purchase through the Kenneth R. Trapp Acquisition Fund.

“This Present Moment: Crafting A Better World” draws some of these energies from Indigenous philosophy and practice, summed up in the exhibition in an essay by Anya Montiel as “Respect, Reciprocity, and Responsibility.” Kevin (Ogala Lakota, b 1958) and Valerie Pourier’s (American, b 1959) “Monarch Nation” exemplifies these necessary virtues. Monier writes, “Pouriers’ buffalo-horn spoon with inlaid orange sandstone and mother of pearl, continues a long-ago artform and ensures that little of the buffalo is wasted. Likewise, the overlapping pattern of monarch butterflies on the spoon’s surface pays tribute to the “small ones” (the insects) and to the annual migration of monarch butterflies from Canada to Mexico. All forms of connection are acknowledged with respect and care.” (cat. p. 174)

I have a daughter who calls herself a craftist and a sewist. “Craftist” insists on equal footing with “artist”; “sewist” repudiates both the female “seamstress” and the patriarchal “tailor.”

Craft doesn’t need defending. Indeed, craft is on offense these days, solidifying its hold on the beauty of the act of making while making significant inroads into art. And if, in the offing, craft transgresses and offends, these artists seem to say, so be it.

“This Present Moment: Crafting A Better World” is on view through April 2 at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum at Pennsylvania Avenue at 17th Street NW. For additional information, 202-633-7970 or www.americanart.si.edu.