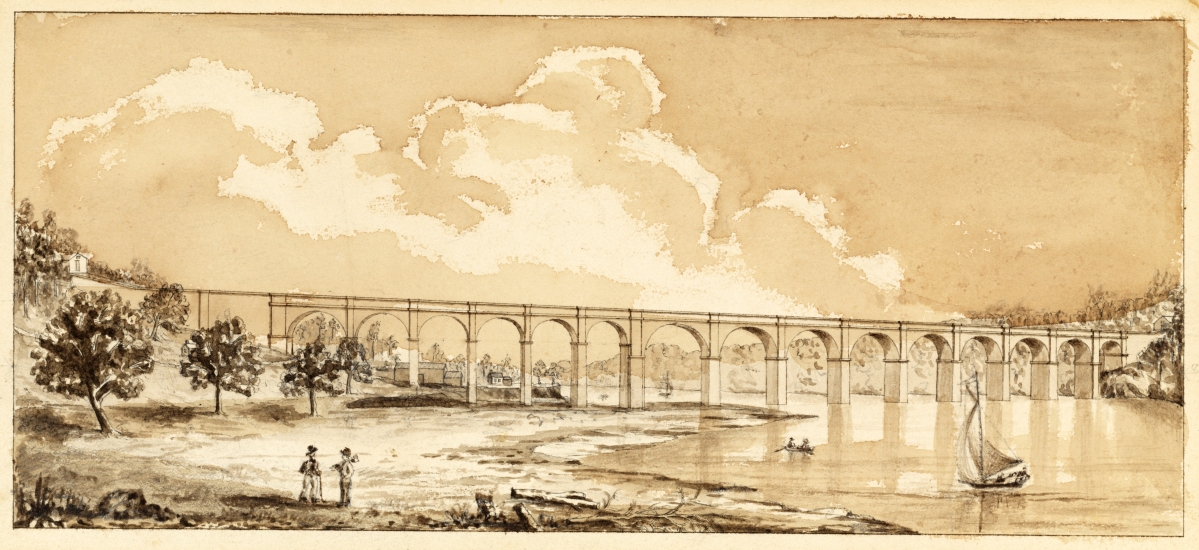

This thoroughfare was considered the “Main Street” of Little Italy at the time the photograph was taken. This image and a companion contemporary photograph by Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao are one of many “then and now” paired projections. “Mulberry Street, Manhattan,” Detroit Publishing Co., circa 1900. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

NEW YORK CITY – “We have high and low and everything in-between. We capture diversity in every sense of the word.” Sarah M. Henry, PhD, deputy director and chief curator of the Museum of the City of New York, so characterized the recently opened “New York At Its Core.” Henry and her colleagues unflinchingly address the tart, sour, rotten and sweet in New York’s history through this permanent museum exhibition, considered the first to cover the sweep of the city’s experience from the early 1600s to the present.

The title of the show obviously refers to New York City’s nickname “The Big Apple.” While there are conflicting theories about the term’s origins, the Oxford English Dictionary indicates that during the early 1920s John J. Fitz Gerald, a writer for the New York Morning Telegraph, used the phrase in the context of New York horse racing, with “apple” referring to first prize. By the late 1920s, “The Big Apple” was equated with “New York City.”

Henry explained, “In the exhibition ‘New York At Its Core,’ we pose the question ‘What makes New York New York?’ as an invitation to visitors to think about what makes this city distinctive and to consider the forces and dynamics that shaped it. For us, the answer lies in four words: money, diversity, density and creativity. Using them as a framework, we look at how New York began as an outpost in a Dutch and Lenape trading network and how it became one of the most important cities in world history, covering the course of 400 years.” The exhibition is designed to provide historical orientation for both New York tourists and residents.

This chronicle highlights municipal and private infrastructure projects, political and economic movements, and other major trends and events. Running in counterpoint are biographical profiles of individual New Yorkers that reveal a range of personal experiences within each era. While the expected Peter Stuyvesant, Alexander Hamilton, J.P. Morgan and Robert Moses are spotlighted, so too are the free-black colonist Maria Van Angola, anarchist Emma Goldman, Chinese American activist Wong Chin Foo and LGBT rights leader and public health advocate Larry Kramer. What is unusual is the dearth of celebratory boosterism generally found in such explorations and the strong emphasis placed upon the lives and circumstances of non-elites and others outside of the power structure, including African Americans, immigrants, working-class people, women, and gays and lesbians.

Henry observed, “It has been a wonderful challenge to formulate and condense New York’s evolution and to select artifacts that carry the story forward.” The subject is huge. Consider the Pulitzer-Prize winning Gotham: A History of New York to 1898 (1998) by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, it totaled 1,416 pages and did not even address the Twentieth Century. Henry and her colleagues have skillfully distilled a complicated narrative while retaining its myriad flavors.

Henry observed, “It has been a wonderful challenge to formulate and condense New York’s evolution and to select artifacts that carry the story forward.” The subject is huge. Consider the Pulitzer-Prize winning Gotham: A History of New York to 1898 (1998) by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, it totaled 1,416 pages and did not even address the Twentieth Century. Henry and her colleagues have skillfully distilled a complicated narrative while retaining its myriad flavors.

Henry led the exhibition team, which included Hilary Ballon and Steven H. Jaffe, as they picked some 400 items for display. These include objects, works of art, archeological finds, manuscripts, printed materials and photographs from private and public collections as well as from MCNY’s own holdings. This is not an object-centered exhibition, but rather one in which artifacts and their kin play a complementary role much like illustrations in a history textbook.

Supplementing these historical resources are large-scale projections of historical New York street scenes that morph into contemporary views of the same areas by photographer Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao, as well as video and audio clips, and still images shared via interactive display.

Demonstrating how objects support themes in the exhibition, Henry pointed to a cocktail shaker epitomizing New York in the 1920s and the changes wrought by Prohibition, a humble cigar maker’s mold representing immigrant workers and the transition from skilled hand-rolling to mass production, and an early typewriter manufactured in Brooklyn that is emblematic of how office work transformed the economic life of the people of New York.

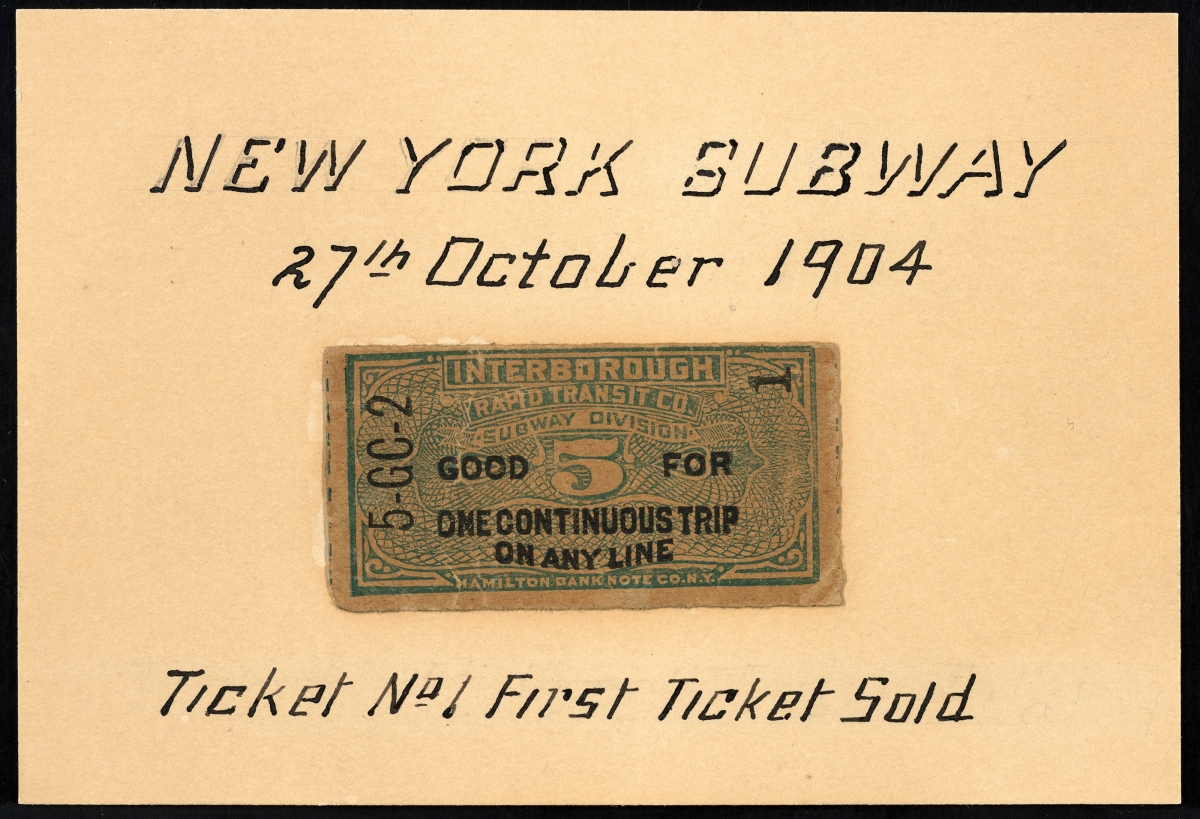

Mayor Robert Van Wyck wielded this ornamental tool at the groundbreaking ceremony for the city’s first subway. Ceremonial shovel made by Tiffany & Co., 1900. Sterling silver and wood.

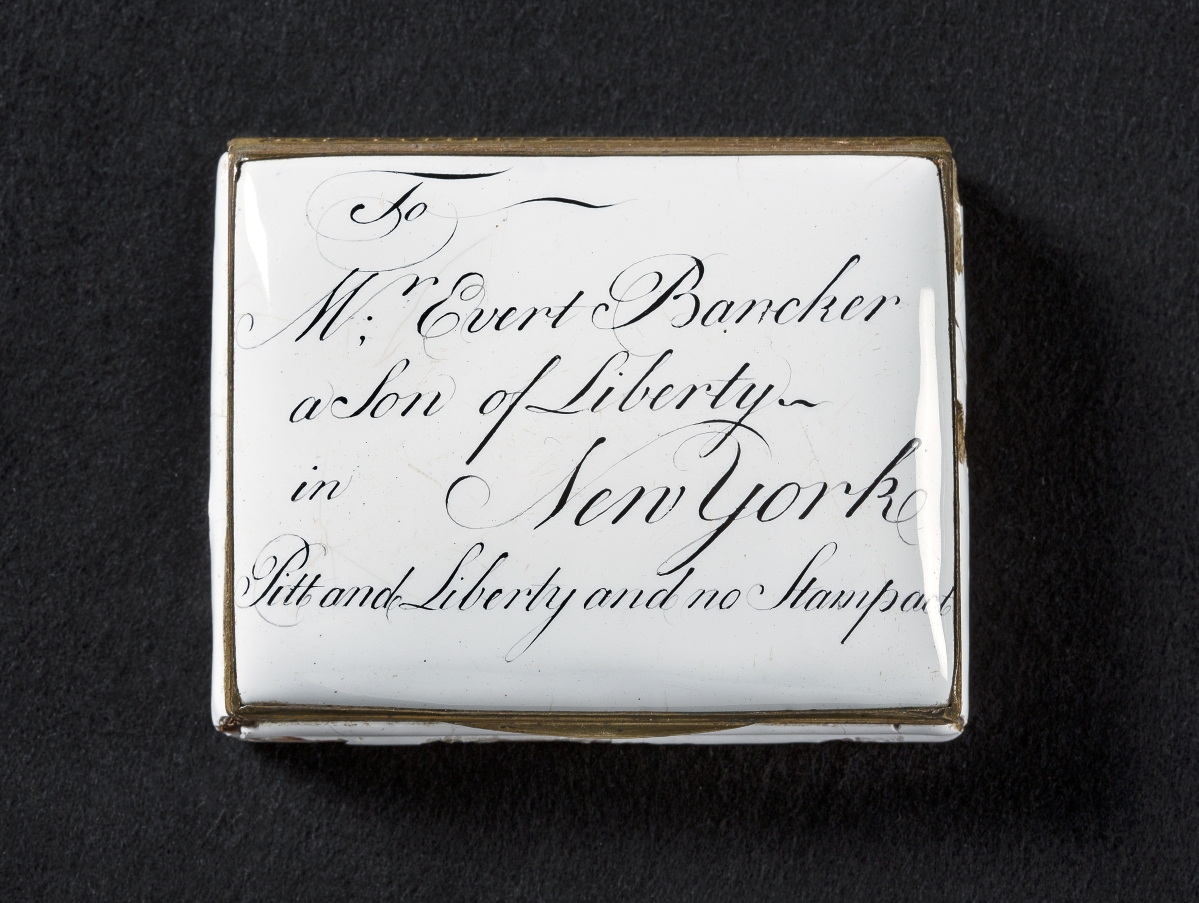

Henry described in greater detail the interpretive value of other artifacts. She drew attention to a silver teapot “with tremendous presence” by Myer Myers. It speaks to the nature of the silver business and the diversity of people in Colonial New York. Myers was Jewish and he created objects for a wide market as well as for the Jewish community. Henry notes, “along with the teapot we have a circumcision shield made by Myers and a circumcision kit on display.”

Likewise, “the Boss Tweed material is fantastic. The cuff links, the bracelets and the walking stick with the Tammany Hall tiger-head handle represent a story that speaks directly to all the themes of the exhibition.” Henry observed, in so many words, that when people hear the term “Tammany Hall,” they usually think of the corruption and the money behind such luxurious objects. William M. Tweed was in a position to embezzle, but this is also about broadening and diversity. He opened the doors of the Democratic Tammany Hall to the new Irish immigrants, recognizing their value as a voting bloc. Deputy Street Commissioner Tweed built out the streets based on the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811. The work of constructing these streets was a lifeline for newcomers with few prospects and resources. The city was realized through jobs, kickbacks and votes. “These objects not only represent the extremes of conspicuous consumption, but also how density, diversity, money and creativity came together.”

Henry underscored the symbolism of the Tiffany & Co. commemorative shovel, used at the groundbreaking of the city subway in 1900, that incorporates “relic” fragments, including gumwood from a tree planted by Alexander Hamilton in 1803 and oak from a vessel involved in the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813. The curator noted, “They were really conscious that this was a historic moment.” She followed, “We think about the subway’s transformational effect on density. It makes population density possible, but it was also a solution to the problem of density. The record-breaking population of the Lower East Side was dispersed across the boroughs through the subway system. As the subway expanded, population rose in Upper Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens and Staten Island and fell in Lower Manhattan.”

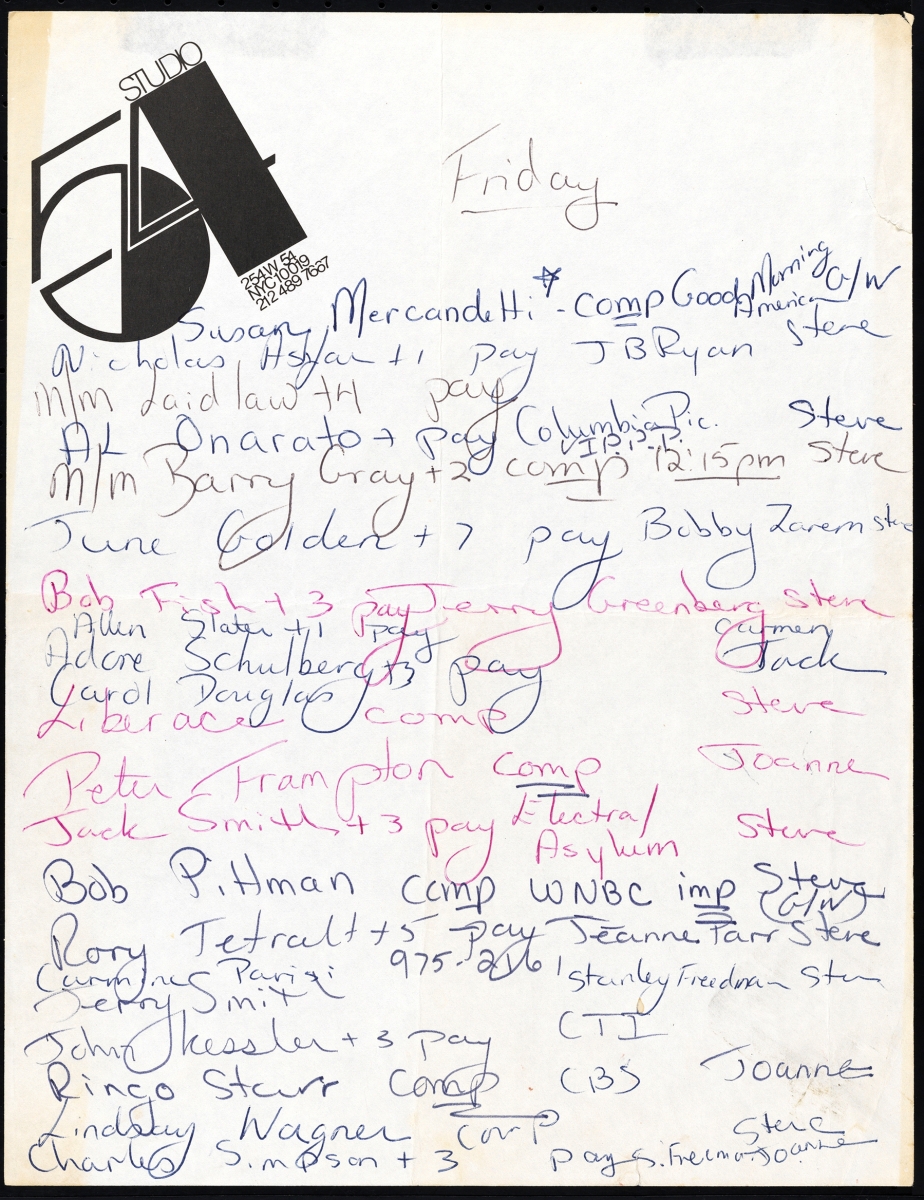

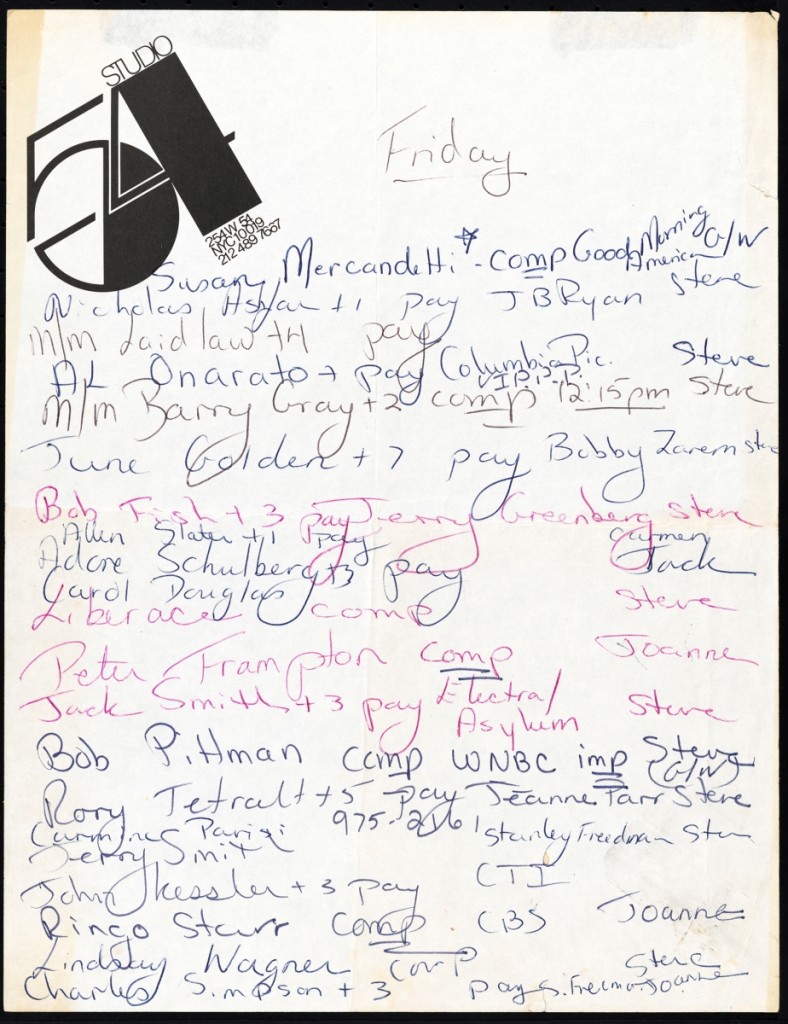

Among the notable names seen here are Liberace, Ringo Starr, Peter Frampton and Lindsey Wagner. More than 400 historical items are on view in the exhibition. Studio 54 Guest List, 1978.

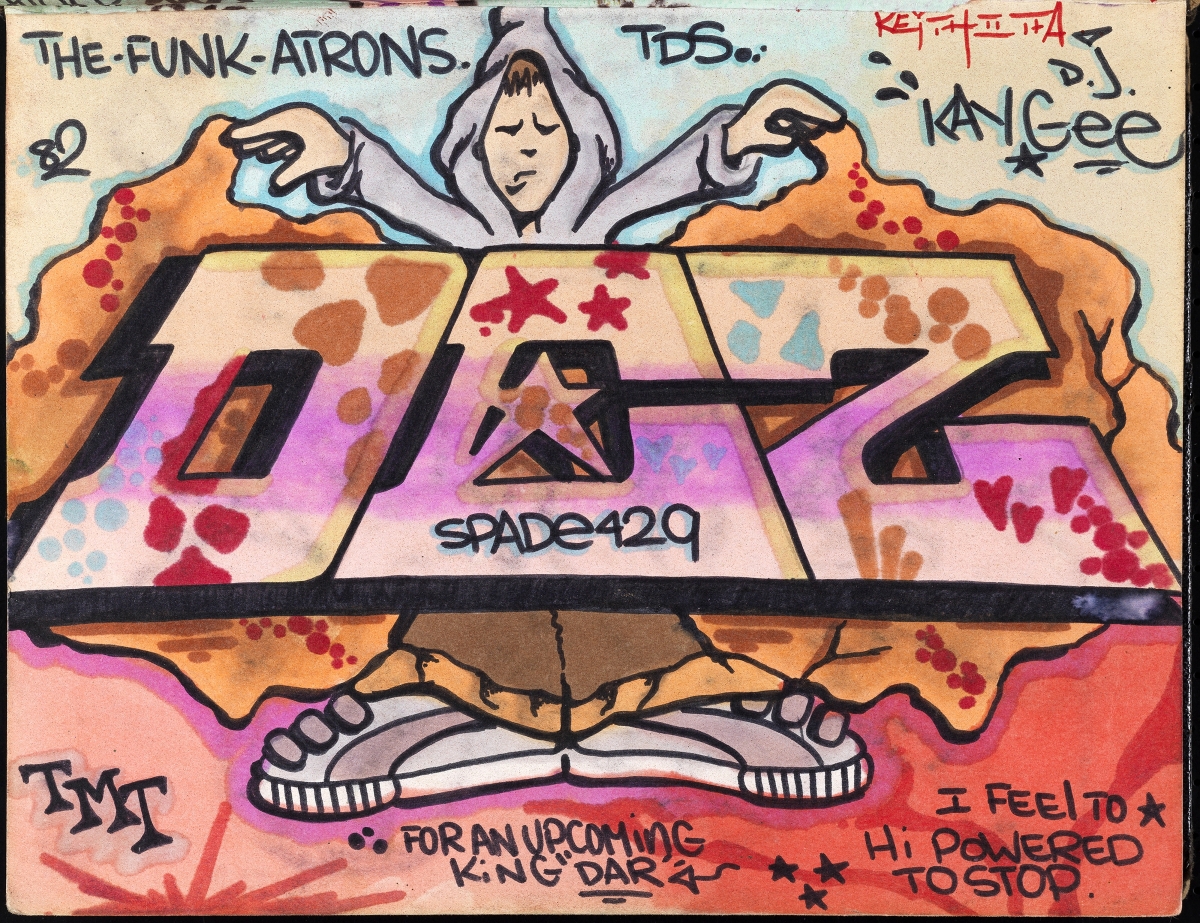

Henry was quick to point out that some exhibition items signify more recent events and movements. These include a Studio 54 guest list, a towel from the Continental Baths, a gay gathering place, and a sketchbook belonging to a graffiti artist of the early 1980s.

Indeed, it is riveting and a bit eerie to see how 1970s and 1980s New York is presented, particularly for those who knew it firsthand. Among the iconic images is a photograph of Mayor Abraham Beame holding up the October 30, 1975, copy of the Daily News with its headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” referring to the city’s fiscal crisis of 1975 and 1976. The interpretive approach to “the best of times and the worst of times” is clinical, not judgmental. During these decades, there was serious concern that the metropolis was on the brink of collapse – or had indeed failed – but Henry and her team have chosen dispassionate reporting rather than expressing a point of view.

The largest gallery is devoted to the Future City Lab. Here museumgoers are invited to learn about, and offer solutions to, issues facing New York in the Twenty-First Century. These include creating modes of housing and transportation to meet impending needs, ensuring opportunities for newcomers and responding to the threat of rising waters resulting from climate change.

While it could be argued that the concepts of money, diversity, density and creativity are applicable to most cities and not solely to New York, their use as an organizing principle is highly effective. Sarah M. Henry and her colleagues have done a monumental job paring down a complex story to its essence. A comprehensive, imaginative and inclusive exhibition stands as the fruit of their labors.

The Museum of the City of New York is at 1220 Fifth Avenue in New York City. For more information, contact www.mcny.org or 212-534-1672.

Kate Eagen Johnson is an expert in American decorative arts and an independent museum consultant, historian, lecturer and author.