By James D. Balestrieri

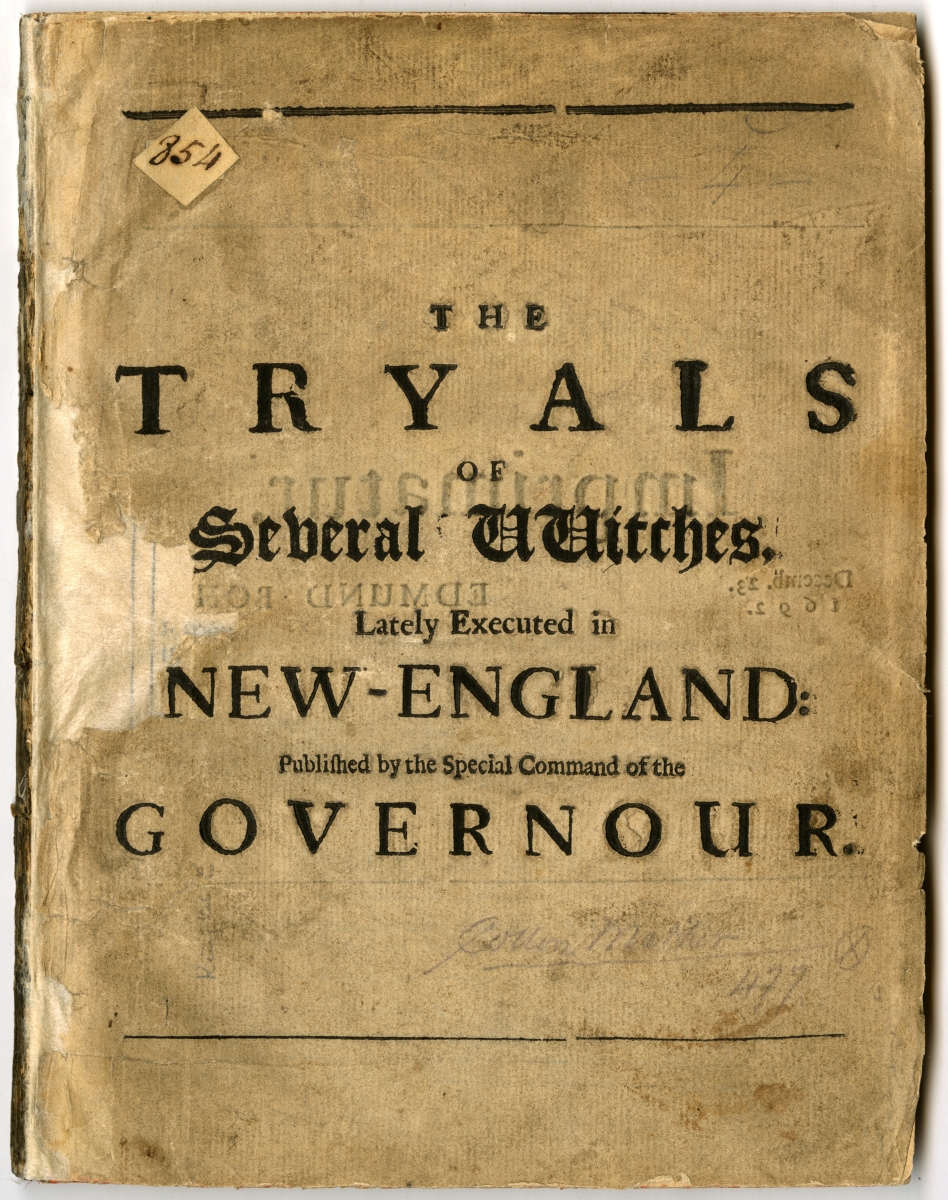

NEW YORK CITY – Science and reason nudged magic aside. In the age of enlightenment, an era of reason – and revolution, let us not forget – dawned in Europe and her colonies in the Eighteenth Century. Magic, which had, since the dawn of religion, been viewed not only as real, but also as an integral part of life, began to be severed from ordinary reality.

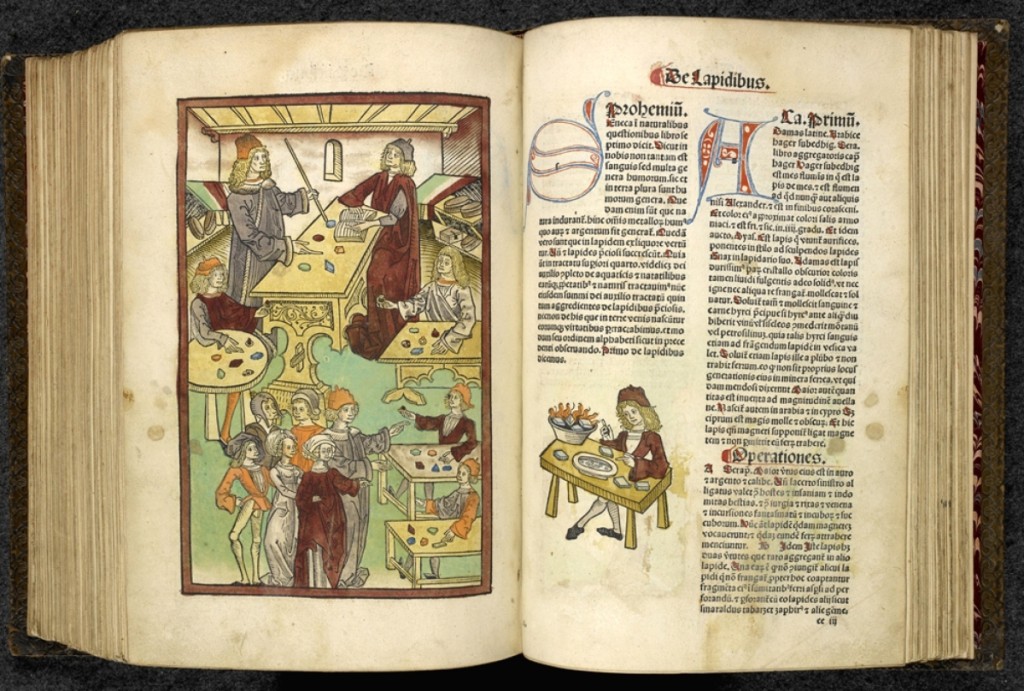

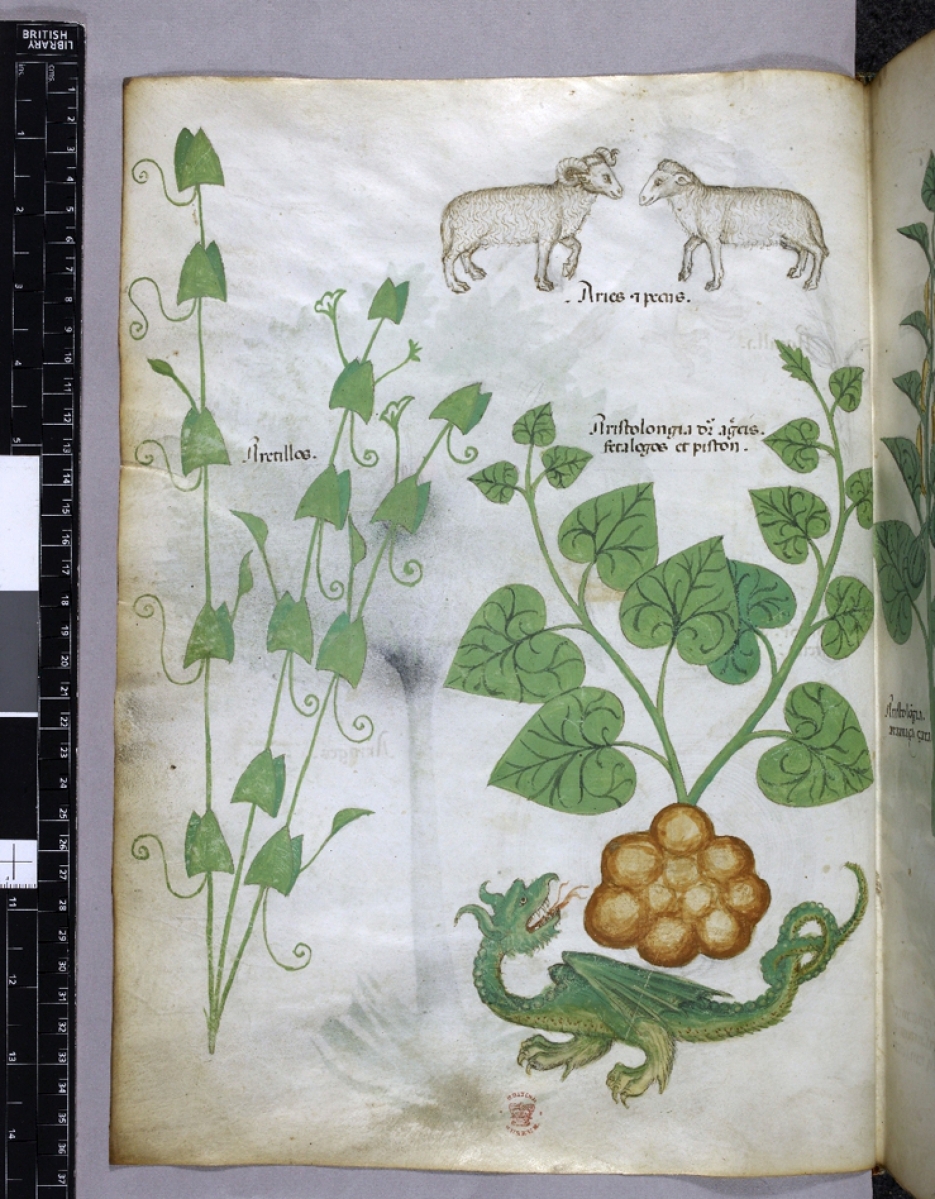

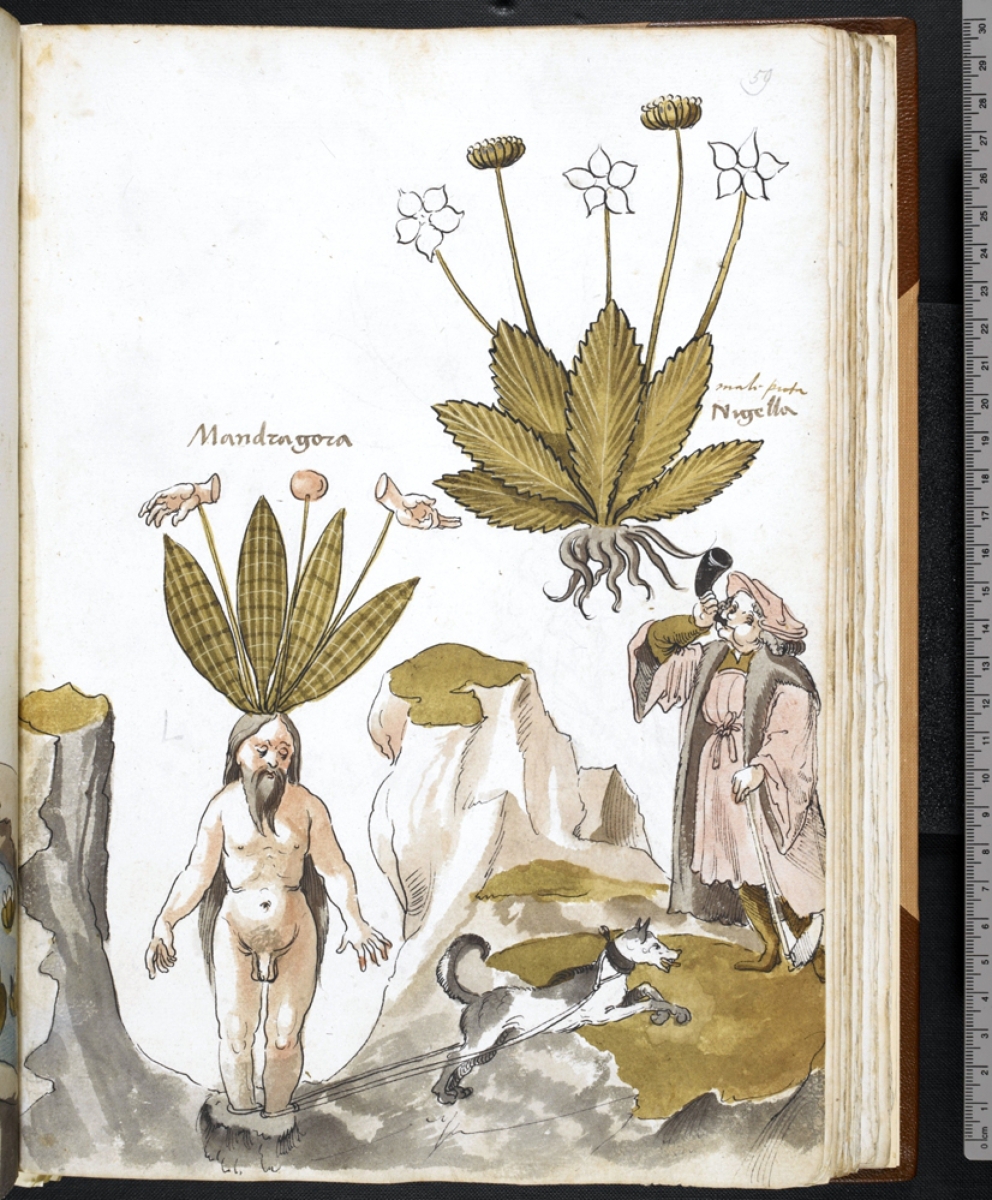

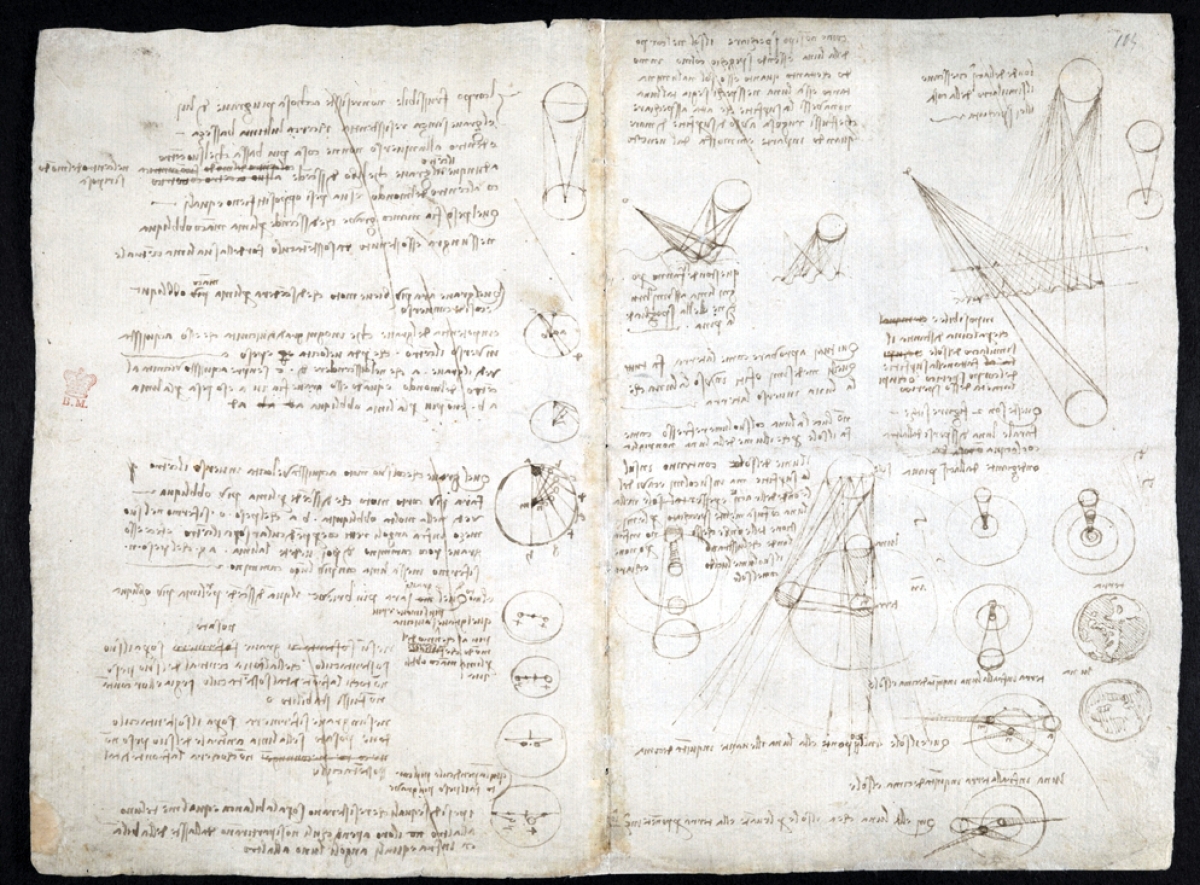

Alchemy became chemistry. Philosophy shed its philosopher’s stone. Astronomy left astrology behind. Herbology split into botany and medicine. The notion of spells, of casting them and falling under them, morphed into the studies of mesmerism, hypnotism and psychology. Electricity no longer came from a wand, but could instead be captured and studied. If you are a Harry Potter fan and planning on seeing “Harry Potter: A History of Magic,” the exhibition celebrating the twentieth anniversary of the American publication of the first novel, to be presented at the New-York Historical Society after its smash run at the British Library last year, you see where I am going with this.

It is not that magic, or magical worlds and beings, disappeared. (I did not say science and reason performed the “evanesco” spell on magic, only that they nudged magic aside.) Magic did not, in fact, disappear; it went underground, as in Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere, or resided somewhere in between, with J.R.R. Tolkien’s hobbits and elves, or continued to exist right alongside us in our obliviated Muggle Earth, as in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels – and films, fanfiction, websites, merchandise, theatrical plays and theme parks that followed. Magic transformed from something we desperately wanted to avoid – a mechanism of real evil at work in the world – to something we desperately wanted to escape into via the conduit of fiction: a realm of fantasy and adventure that the rational world denied us.

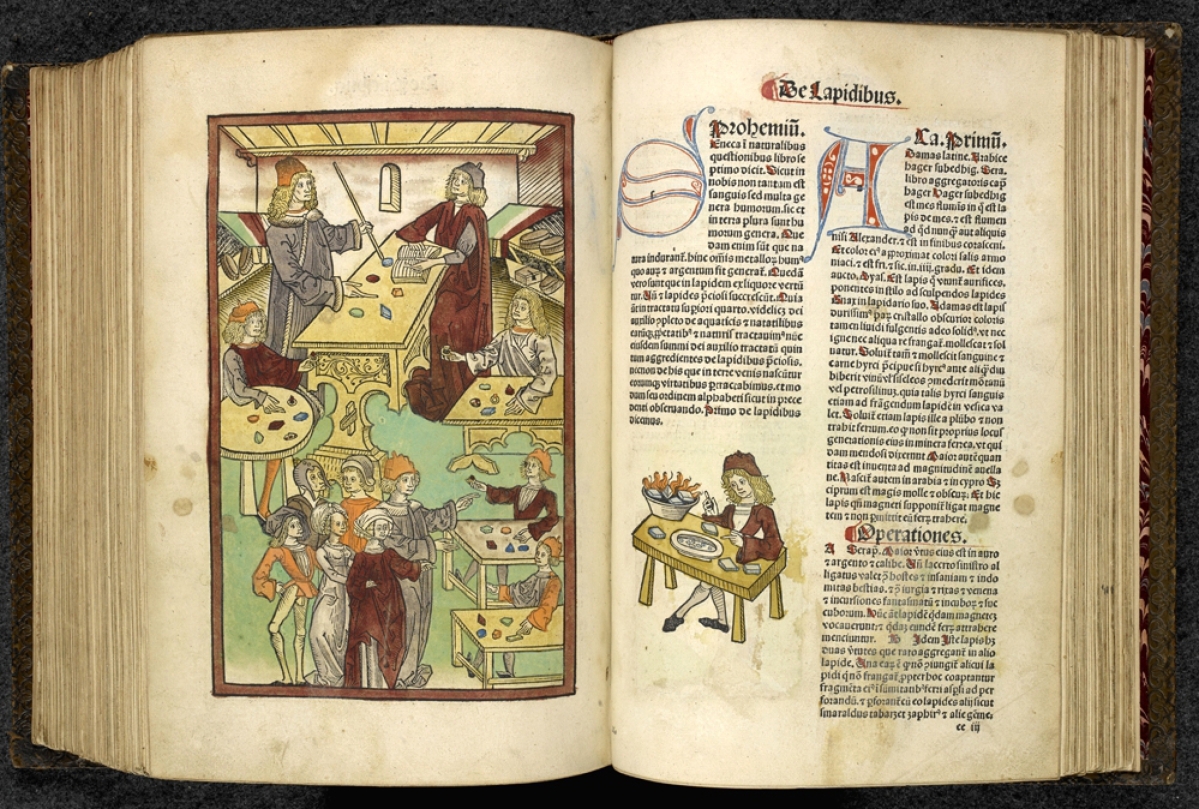

Like Gaiman, Tolkien and many others, Rowling creates a world out of whole cloth. It is centered around Hogwarts, the ancient school of witchcraft and wizardry that Harry attends in order to learn to hone and control skills he is only dimly aware of and to come to terms with his destiny as the chosen hero who must oppose the villainous Voldemort’s machinations. But Rowling distinguishes herself from other authors by creating connections between the world of Harry Potter and ours, making key references to actual figures and impedimenta from the age before reason, when magic was in season and very much believed in. The exhibition is split between Rowling’s manuscripts – early notes, drawings and original illustrations for her books – and medieval illuminations depicting alchemists and herbologists at work, crystal balls, witches’ brooms, magic stones and more. These, in turn, are organized by the Hogwarts curriculum, the subjects that Harry studies: Divination, Defense Against the Dark Arts, Care of Magical Creatures and so on, in which objects from the history of magic correspond to specific aspects of the novels.

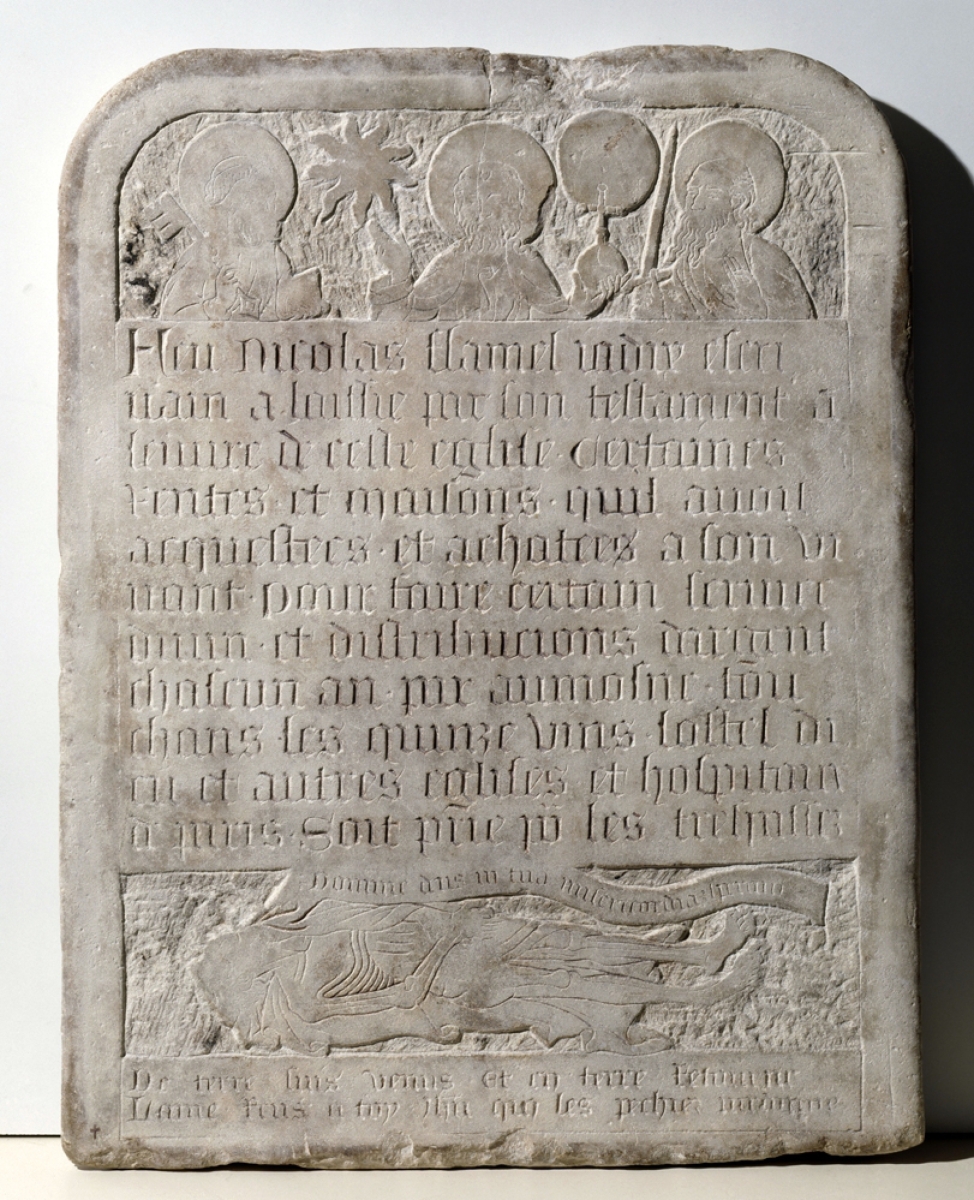

For example, the tombstone of the historical medieval French scribe Nicolas Flamel, who lived from 1340 to 1418, is on display. A respected scholar in his lifetime, Flamel’s legend – which Rowling draws on in her first Harry Potter novel, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Sorcerer’s Stone here in the US) – states that he had ferreted out the secret of the philosopher’s stone, allowing him to turn base metal into gold, and that he had also discovered a recipe for immortality. What is fascinating is that it was not until the Seventeenth Century that Flamel acquired his mystical, cabalistic reputation – one that only grew over time. Flamel himself does not appear in Harry Potter (he actually has his own young adult series of books), but the stone and its power to confer immortality is the MacGuffin in the story.

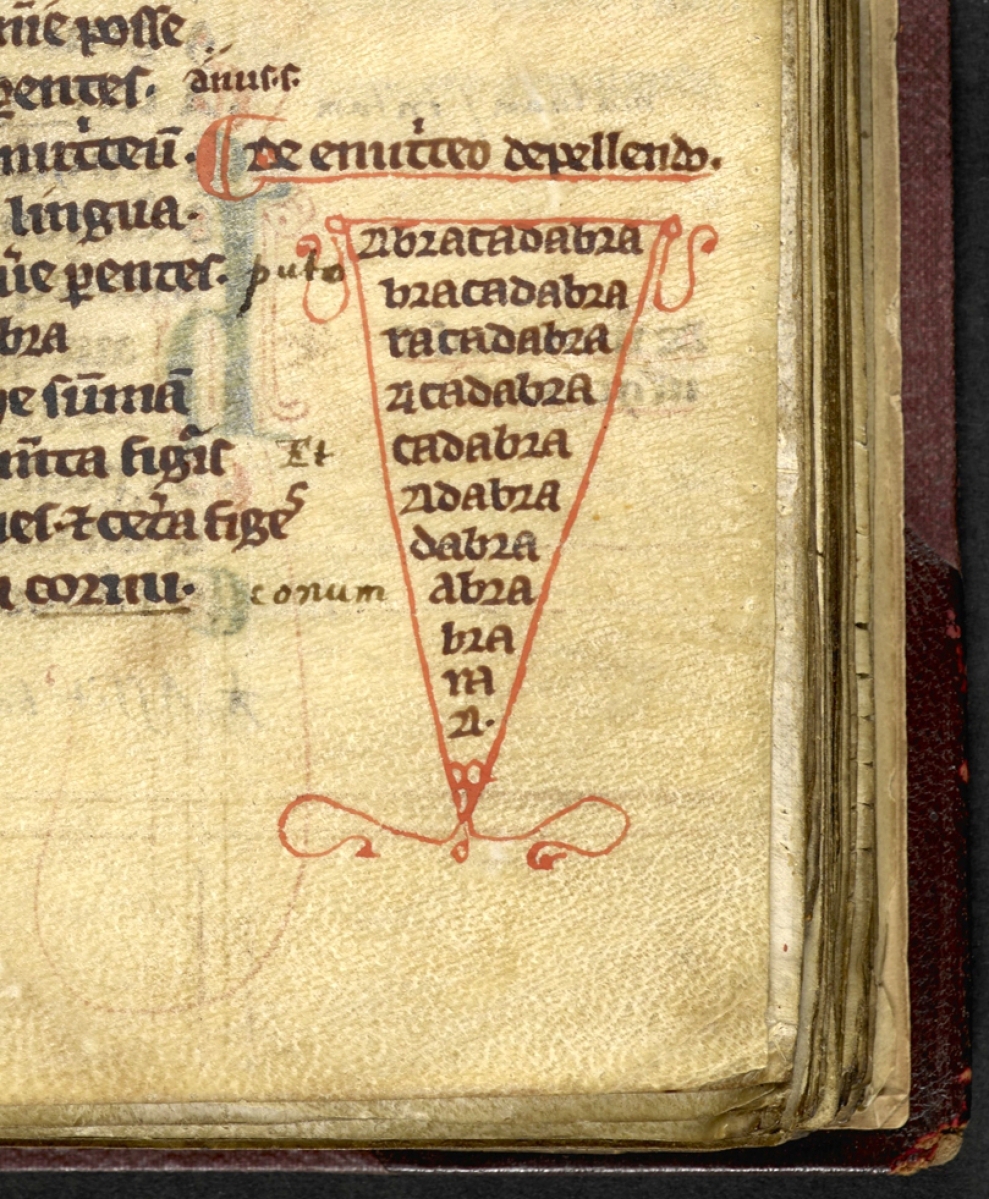

The first documented appearance of the most famous magic word of all (apart from “please,” which is what Harry demands from his horrible aunt, uncle and cousin in the second novel, once he realizes the power he has) is on display in the exhibition. “Abracadabra,” offered as a cure for malaria in the Thirteenth Century manuscript Liber Medicinalis, appears here as a kind of acrostic inscribed within an inverted triangle, a feminine water symbol in alchemy. One wonders if the malaria sufferer has to recite the word down, up, left to right and right to left, adding and subtracting letters in order to flush the fever out (in the Harry Potter books, the business end of “Avada Kedavra” means instant death – hardly a healing spell).

Bezoar stones, the undigested residue found in the stomachs of ruminants, were thought – and not only by Professor Snape – to ward off the effects of poisons. The dark, slick ball in the exhibition is encased in exquisite gold filigree, testifying to its Arabic origins. Bezoar, as the book accompanying the exhibition states, means “antidote” in Persian. What is less clear is how the stone was used. Do you take a piece off it and mix it into a potion, or does the mere possession of it ensure immunity?

Magic has had its faddish revivals, notably in late Nineteenth Century spiritualism and fairy photography and in the craving to contact the dead that seemed to arise after the horrors of World War I – think seances and the Ouija board. A number of modern items in the exhibition attest to these periodic spikes in magical interest.

Twentieth Century English witch Olga Hunt’s broom, though it does not compare to Harry’s Firebolt, bore Olga over Dartmoor on the night of the full moon, as legend has it. It is hard to imagine such superstition in the not-so-long-ago, but our wish and will to believe in magic reaches more deeply and broadly than our hyperrational minds can conceive. Every lottery ticket purchased, every internally incanted wish for luck, is a rabbit’s foot we keep to ourselves, the leap onto Olga’s broom or into the witch “Smelly Nelly’s” black moon crystal ball. Smelly Nelly got her nickname because she thought her strong perfume attracted spirits, though making her clients’ eyes water and clouding their vision might have been another reason.

Objects from the larger world of Harry Potter, such as the set models and costumes for the West End and Broadway play, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, a sequel to the novels, will represent the cultural phenomenon that the story has become, and the exhibition will be accompanied by many events for children and adults. Wand making, spell casting and cosplay will be among them, but the events featuring artists who have illustrated Rowling’s seven novel saga – as well as their original artworks – seem particularly appealing. Mary GrandPré, Jim Kay, Kazu Kibuishi and Brian Selznick have – or will have, in Selznick’s case – adapted their several styles to the material: GrandPré sees the Harry Potter novels as if through a child’s eye; Kay finds the Gothic darkness in adolescence and the painful trials of adulthood and responsibility that Harry and his friends face.

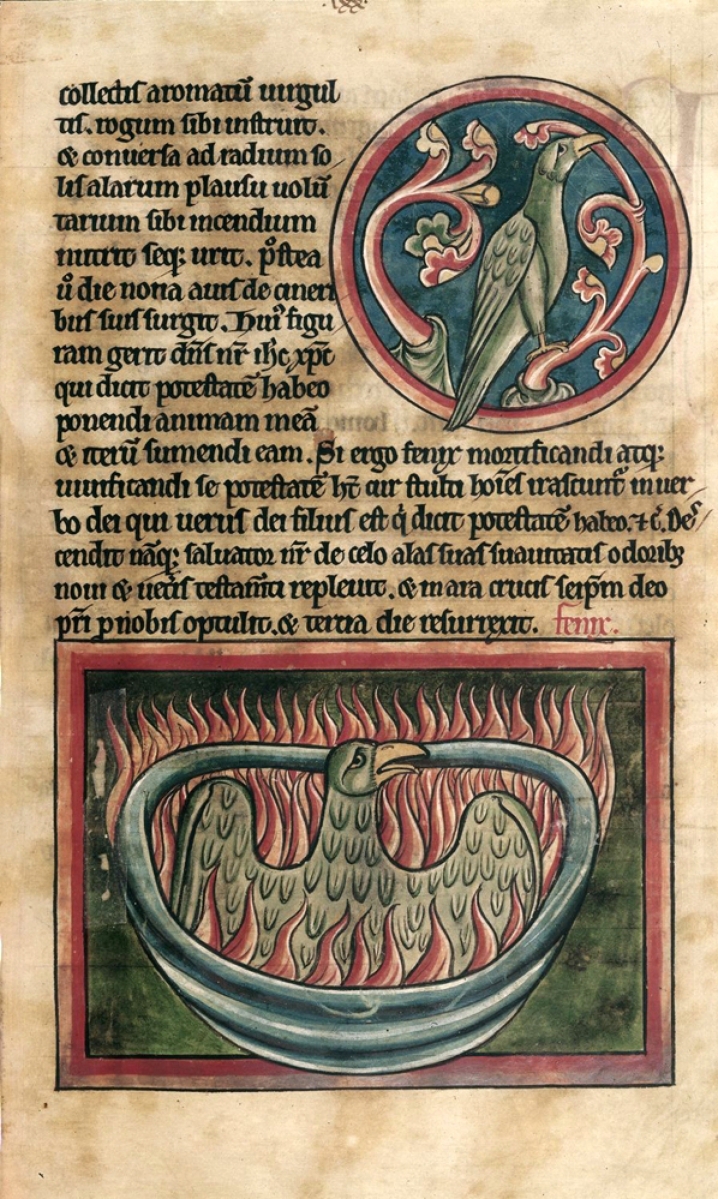

I myself am hoping to see how each artist has depicted the phoenix, like Hogwarts headmaster Albus Dumbledore’s brave familiar, Fawkes, who goes on to inspire the Order of the Phoenix, the secret society created by Dumbledore to fight Voldemort and his allies and minions. The phoenix, rising from its own ashes, an ancient emblem of resurrection and rebirth, seems to symbolize Harry’s courage, Rowling’s perseverance and the tenacity of magic in the human imagination. Jim Kay’s Phoenix, appearing in the illustrated edition of the series, is a palimpsest overlaid on a faded manuscript page dealing with magical creatures. The brilliant, flowing bird, wings outstretched, seems to have been born of, and to have leapt out of, the words on the parchment, suggesting the spell that the story casts and the images formed in the minds of readers.

Of course, there are other forms of magic. There is the practice of illusions, the trade of professional magicians that closes the loop and takes us back beyond reason, where the senses give way once again to imagination; whether it is Houdini or David Blaine, we cannot figure how they did that if they are not in league with dark powers. The stuff of magic – the apparatus of illusions, posters, books and manuscripts – is hot property at auction. Entire sales are devoted to magic. Couple that with the popularity of Harry Potter, the sensation across generations and in many languages, and you have to ask what yearning – or absence – magic speaks to and fills.

And then there is the magic in science itself, made manifest from the time of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, harnessed by mountebanks and mesmerists, fakirs and prestidigitators in carnivals and sideshows and passed off as magic, carrying through to the very real wizardry of space exploration, particle physics, genetics and artificial intelligence.

But the underlying implication in “Harry Potter: A History of Magic” is that what Rowling has achieved is itself a kind of magic, the alchemy of transforming words into beloved tales. Her own story, the very real hardships she endured as she labored to bring Harry Potter into being, and her ultimate belief – her faith – in her creation appear to us, especially to those of us who write, as magic of a high order, combining Divination (visualizing success), Defense Against the Dark Arts (rejection and despair), and Care of Magical Creatures (words can be tricky beasts) into a single, hard course of study in a school of magic older even than Hogwarts. Most of us matriculate into this ancient school for writers, disappear into its labyrinthine corridors like so many interns at the Ministry of Magic and are never heard from in the world at large. Rowling and her Harry are indeed magical.

“Accio!” is the spell that the New-York Historical Society casts, summoning you to “Harry Potter: A History of Magic.”

The exhibition opens October 5 and continues through January 27. The New-York Historical Society is located at 170 Central Park West. For more information, www.nyhistory.org or 212-873-3400.