“Knickerbocker Stage Line Omnibus, New York City” by William Seaman (active 1840s-60s), circa 1850, oil on canvas. New-York Historical Society, Gift of the Estate of George Shepherd, 1912.8.

By Madelia Hickman Ring, Editor

NEW YORK CITY — Residents of — and visitors to — New York City may not be aware of how much the current landscape of the city has changed over time. A new exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, which is scheduled to remain on view through September 29, explores once-vibrant neighborhoods and lost landmarks. Drawn entirely from the museum’s collection, the exhibition, “Lost New York” is curated by Wendy Nālani E. Ikemoto, the museum’s vice president and chief curator and features nearly 100 paintings, photographs, lithographs and objects that offer a tantalizing glimpse into the city’s rich heritage of landmarks and monuments as well as sites related to transportation, leisure, nature and communities.

The specific topic is not one that’s been previously explored in such depth and Antiques and The Arts Weekly asked Ikemoto what prompted the exhibition’s development.

“The exhibition concept has been on my mind for a while, but really got off the ground when I helped the museum acquire two large painted renderings of the city by Richard Haas (b 1936) that combine Nineteenth and Twentieth Century views of the city. You can see the dramatic difference in the landscape,” the curator shared.

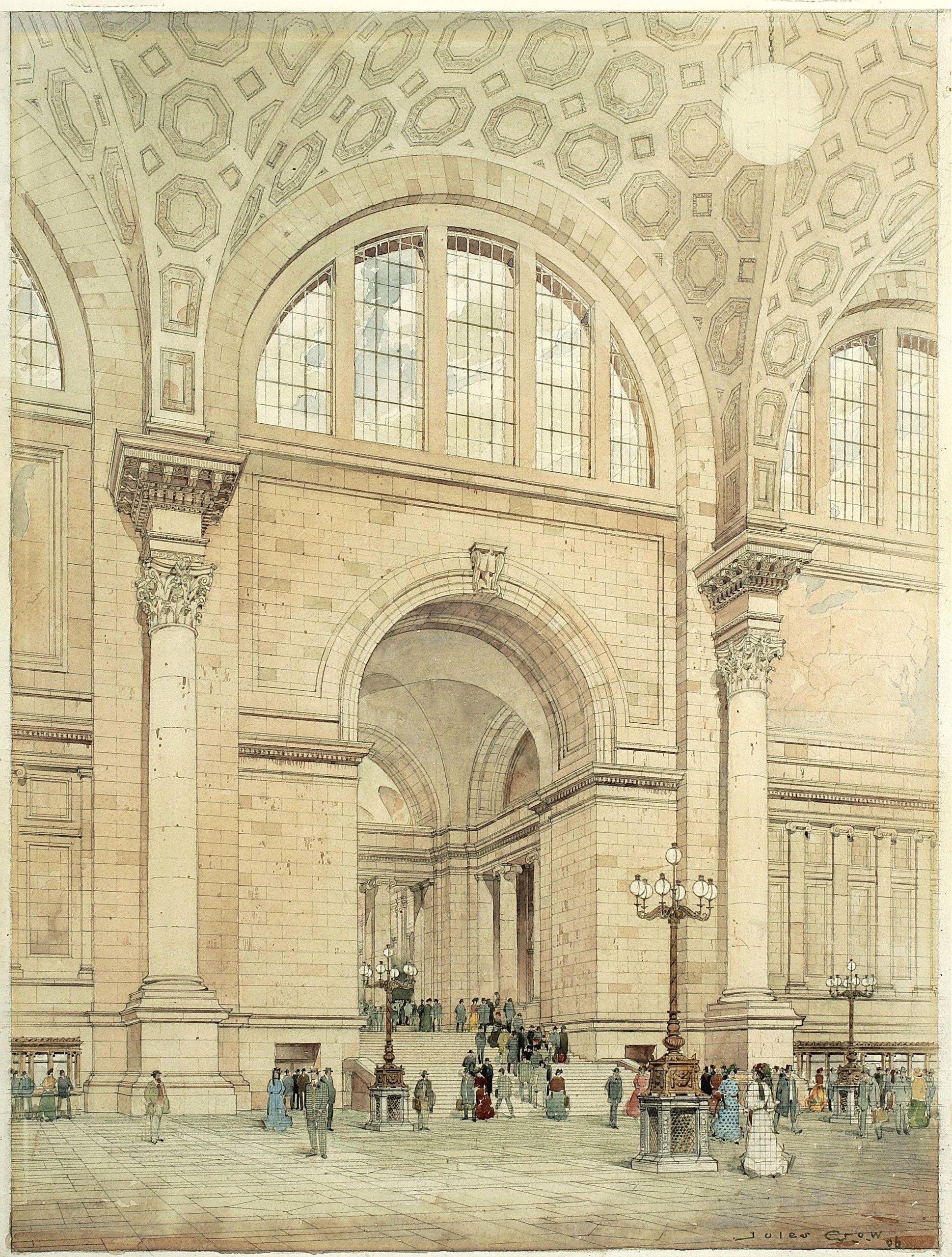

“Pennsylvania Station Interior” by Jules Crow (fl 1905–1906), 1906, watercolor, ink, and graphite on paper. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society.

In 2012, architectural and art historian and Yale professor Vincent Scully told The New York Times that through Pennsylvania Station “one entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat.” He was referring to the old McKim, Mead and White-designed Beaux-Arts building that opened in 1910 and was demolished in 1963 (the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission was formed in 1965, spurred by its destruction). One of the highlights of the exhibition is a watercolor, ink and graphite drawing of its interior, done by Jules Crow, that captures its awe-inspiring and dramatic 148-foot-high coffered ceilings.

Penn Station was one of just several architectural wonders no longer extant but which are featured in “Lost New York.” The Latting Observatory, a 315-foot-tall iron-braced wooden structure at the corner of 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue, was built in 1853 for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. Once the tallest structure in the United States, it offered sweeping views of the city from three tiers of viewing platforms but burned down in 1856.

New York City’s Crystal Palace, built in 1853 to house the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations and modeled after London’s Crystal Palace of 1851, was deemed “loftier, fairer, ampler than any yet” by no less than Walt Whitman. The poet was among those who visited the glass, steel and iron building — then considered the largest in the western hemisphere — to marvel at the technological wonders on display. It also burned down, in 1858; a vestige of its footprint survives in what is now Bryant Park, behind the New York Public Library.

“New York Crystal Palace for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations” by François Courtin (1820-1871), printed and published by Veuve Turgis (active 1826-1864), 1853-54, hand-colored lithograph. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society, Gift of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot, 1941.

Omnibuses – large horse-drawn stagecoaches that ran on designated routes – were the city’s first form of public transportation, foreshadowing the streetcars and, eventually, the subways and buses that New Yorkers now rely on. One of the lines, the Knickerbocker Stage Line Omnibus, which operated from 1835 to 1865, ran out of Knickerbocker Hall, its main depot at 23rd Street and Eighth Avenue. A painting by William Seaman brings both the vehicle and its depot to life.

Edifices that hosted leisure activities for New Yorkers are also among those that remain a faded memory and play a prominent part of the exhibition. These would include the Chinese Theatre, located at 5-7 Doyers Street, which opened in 1883 and was the first Chinese language theater on the East Coast. Uptown, at 43rd Street and Sixth Avenue, the New York Hippodrome (1905-1939) had a seating capacity of 5,300 and was billed as the largest theater in the world. A Gilded Age marvel, the Old Met Opera House opened in 1883 at 39th Street and Broadway. Proving too small, the building was torn down in 1967.

Many readers may be surprised to learn that in the Nineteenth Century, pigs once freely wandered the city streets; as many as 20,000 in the 1820s. The pigs were owned by the working class, who saw them as a ready source of food and income by selling them to butchers. Ultimately, when wealthier New Yorkers complained that they blocked traffic and created a stench, a series of policies were enacted, including the 1859 law that pigs were not allowed in Manhattan south of what is now 86th Street.

“No. 7½ Bowery, New York City” by De La Prelette Wriley (active in New York, 1842-1850), circa 1837-39, oil on wood panel. New-York Historical Society, Purchase, 1936.799.

A painting by De La Prelette Wriley (active 1842-1850) of “No. 7½ Bowery, New York City” memorializes this cultural phenomenon by including a black and white pig in its foreground.

An innovative aspect of the exhibition is the inclusion of community voices that breathe life into these structures. Among these, a woman remembers attending the Old Met Opera House in 1939, when she was seven years old. A Broadway carpenter reminisces about a photograph of his father in front of the Hippodrome Theatre. The demolished Harlem Renaissance moment, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” inspires reflection from a choir director.

Two works by Anne Eisner show the Union Square department store, S. Klein, which was in business from 1906 to 1975, selling everything from clothing to furs, jewelry and pet supplies. “Klein’s Inner Sanctum” and “Klein’s Outer Sanctum,” both circa 1934-38, speak to a space that was both public and private. A woman who shopped at Klein’s as a child added her voice to other community ones, recalling, “Because we had little money, Klein’s was the only place my mother took me for clothes. While some items were on hangers, there were mostly tables piled high with unfolded clothing which the women would grab over one another.”

“Untitled (View of Manhattan Looking South toward the Empire State Building)” by Richard Haas (b 1936), 1994, acrylic on canvas. New-York Historical Society, Gift of Cooley LLP, 2022.41.2. Image ©Richard Haas.

Ikemoto recognizes the importance of bringing in contemporary recollections, which she feels also helps the exhibition break new ground. “It’s really meaningful to have voices from people connected to these sites bring them to life. We want to prompt people to think not only about what’s been lost and the socioeconomic drivers that led to those losses but also about how the past lives on and how history matters today.”

The New-York Historical Society is at 170 Central Park West, at Richard Gilder Way. For information, www.nyhistory.org or 212-873-3400.