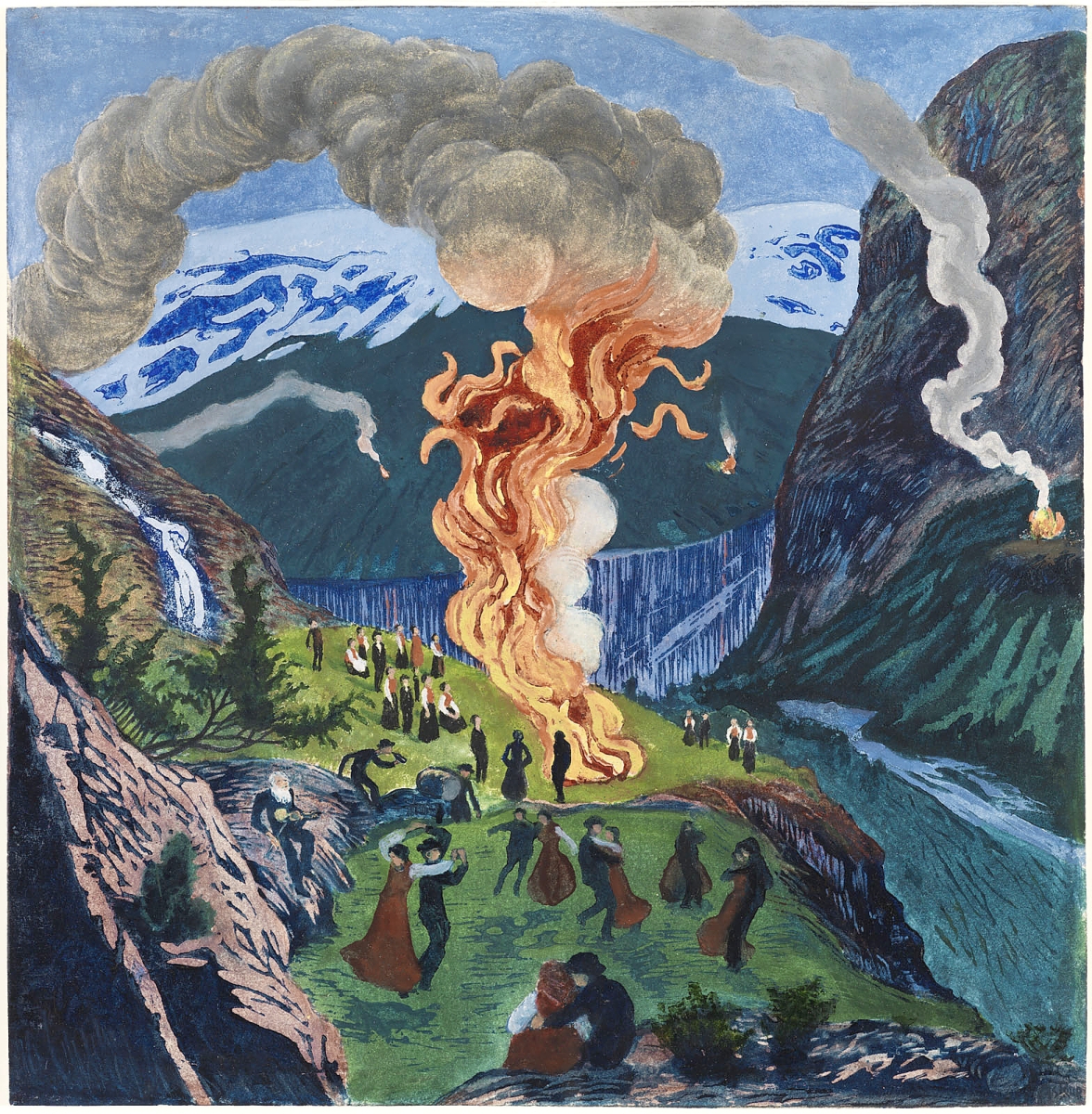

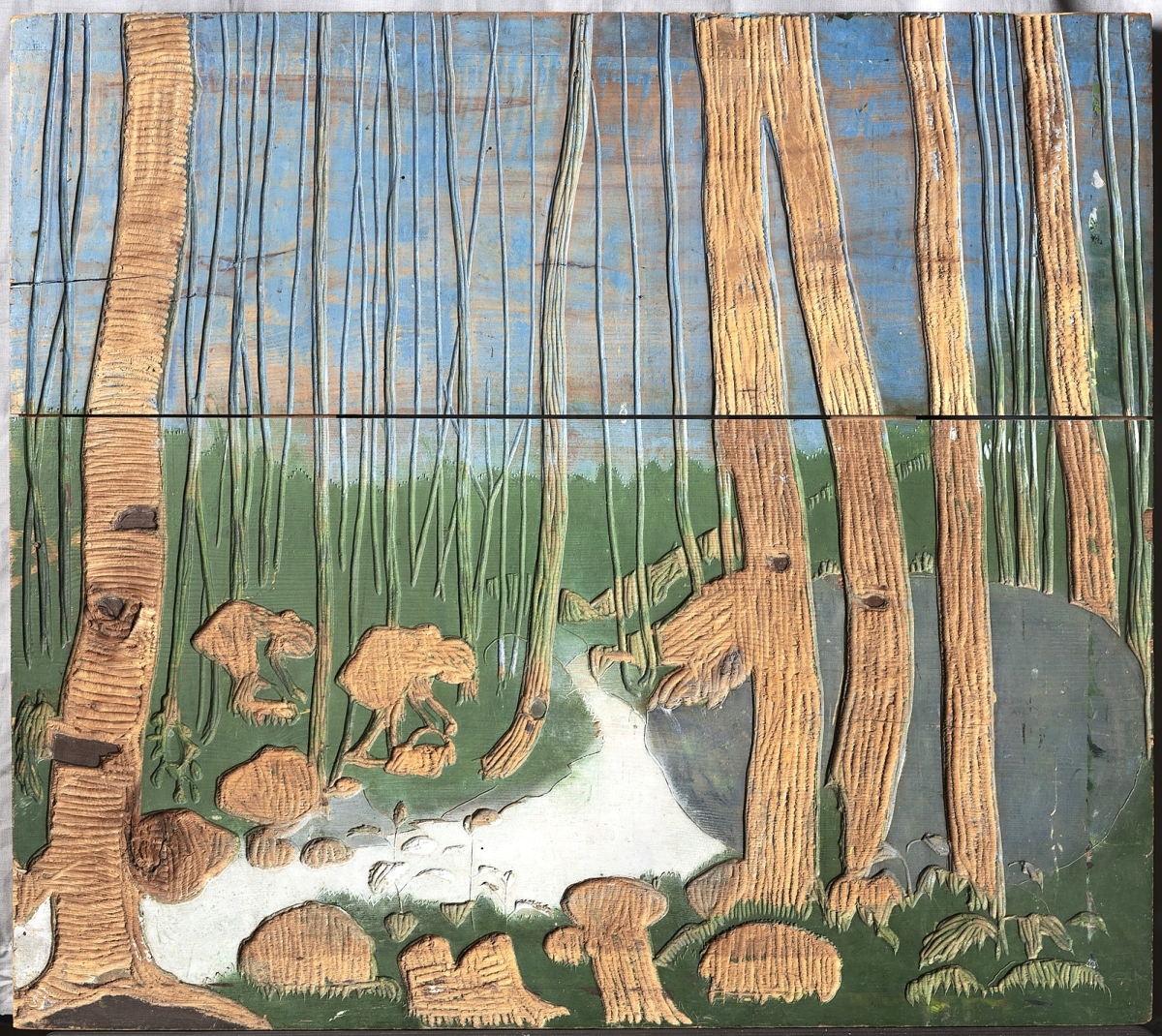

“Midsummer Eve Bonfire” by Nikolai Astrup, woodblock before 1917, print after 1917. Color woodcut on paper. Private collection.

By Kristin Nord

WILLIAMSTOWN, MASS. – As gifted as Edvard Munch, Henrik Ibsen and Edvard Grieg, Norway’s well-recognized triumvirate, Nikolai Astrup (1880-1928) was an original – an artist highly revered at home and yet largely unknown to the wider world.

“Nikolai Astrup: Visions of Norway” celebrates this remarkable Norwegian painter, printmaker and horticulturist in a stunning retrospective at the Clark Art Institute as it presents major works from Norwegian public and private collections in the United States for the first time. In it we encounter a brilliant artist and innovator whose mission was to capture the essence of the specific region in Western Norway where he lived and worked throughout his life.

To Hans E. Knick (1865-1926), Astrup’s great friend and considered by many to be his literary counterpart, “Astrup painted in dialect” – i.e., in that his art, in its directness and simplicity shared the qualities of folktales. Edvard Munch, a generation older, asserted that Astrup captured Norway’s greens as no one else could.

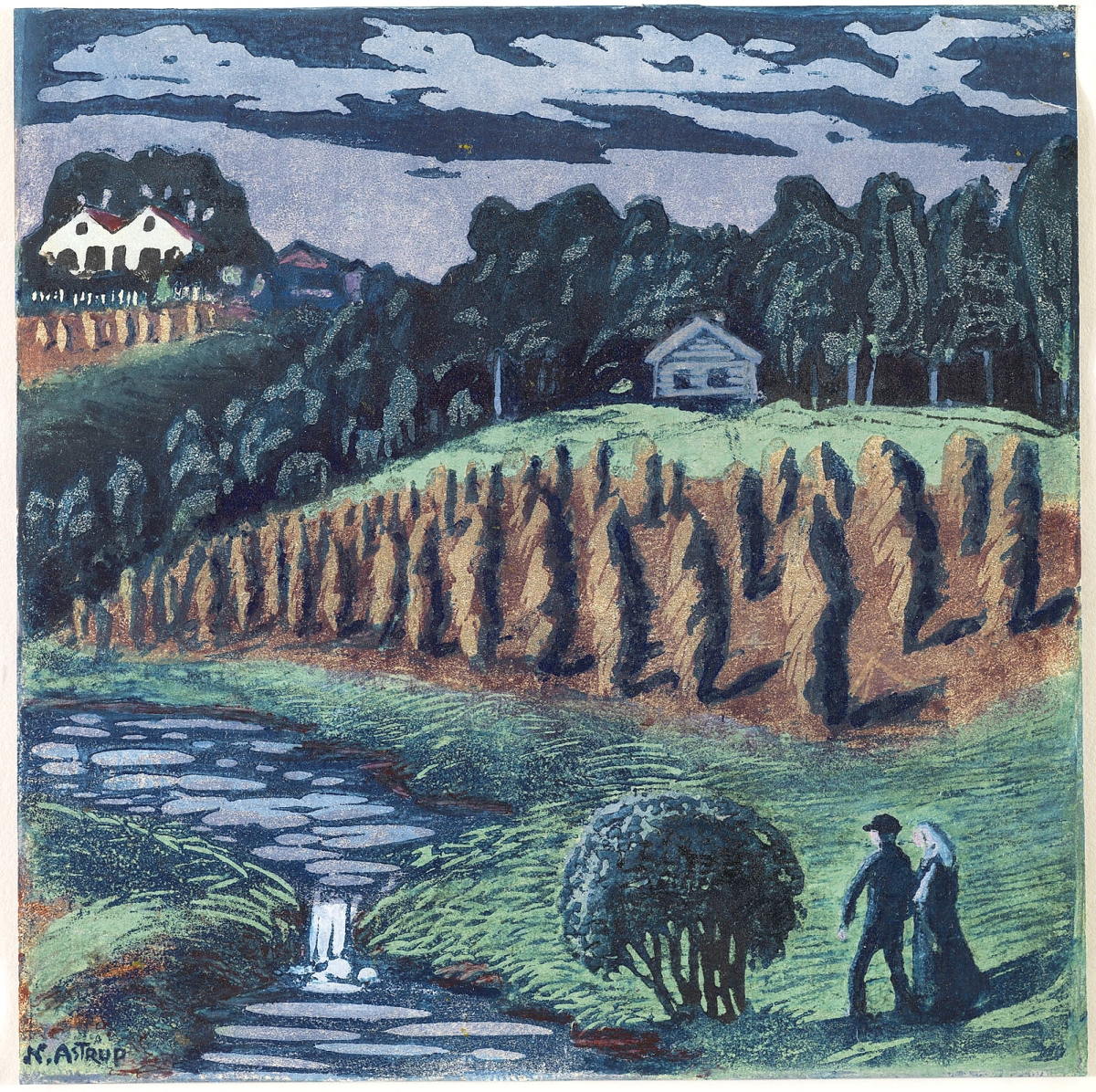

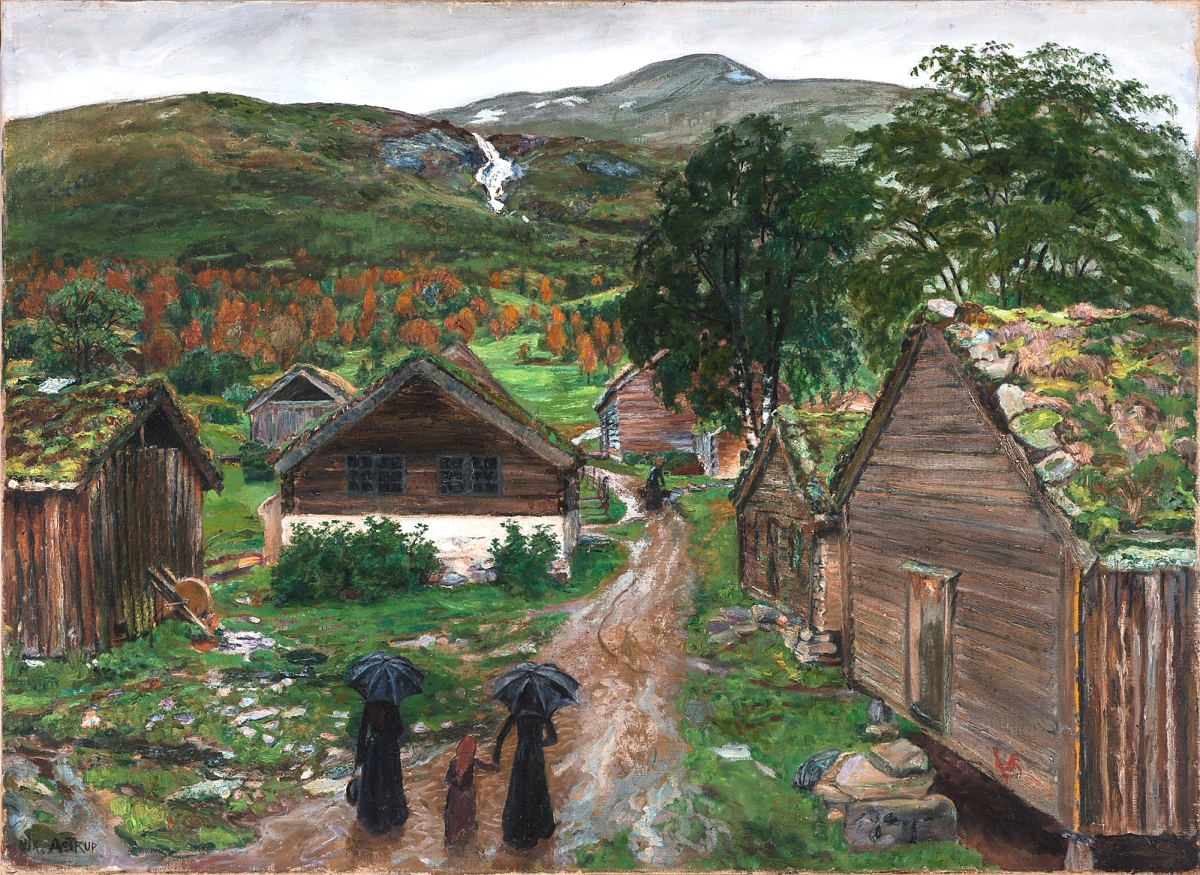

Childhood memories, and the scenes of the homestead where he’d been reared, would provide him with a kind of poetic shorthand that would inspire him throughout his short life. The writer Karl Ole Knausgård, on a visit to his mother, who lived nearby, came back with this field report: “Everything that we could see, the artist had painted. The main house of the parsonage, with its shimmering white walls, the garden outside, the church below, the valley beyond, the mountains above. And they are just not any old paintings, but paintings aglow with color and simplified planes, which give them a powerful radiance, and which no other art or literature from this part of the country have ever come close to rivaling.”

Norway had voted to dissolve its union with Sweden in 1905 as a new aristocracy of intellectuals replaced the former hereditary aristocracy as the shapers of public opinion. In the succeeding decades, a Norwegian identity would be forged in music, literature, architecture and the visual arts. These intellectuals posited that the essence of Norwegian character was to be found in the peasants of the countryside.

Astrup was reared in the village of Ålhus, overlooking Lake Jølster, the son of the local pastor who was known for his rigidly conservative views and his three-hour sermons. This was a remote farming region only accessible by road north of the lake and by rowboat and steamer during the warmer months.

This was also a region in which the Hardanger fiddle, a traditional stringed instrument similar to a violin, had been banished by the church and was seen as “the devil’s music.” In Astrup’s words, he “and many other children in western Norway, suffered under the fanatic religiosity of the elderly generation. Everything was sinful -even sledding.”

It was a harsh climate in other ways, with intense rainfall up to 90 inches annually and extreme fluctuations in daylight.

Several hours away, Bergen was a bustling cosmopolitan port city and an important trading member of the Hanseatic League. It was also a wealthy and fertile intellectual center, home to the likes of Ibsen and Grieg.

If Pastor Astrup had assumed his erudite son would follow him into the clergy, over time he reluctantly acceded to Nikolai’s dream of becoming an artist. The young man, who suffered from asthma throughout his life and would die an untimely death at 47, had roamed the countryside at all hours during his childhood filling notebooks with motifs that would recur in his prints and paintings. To these he added a fertile imagination steeped in the classic Norwegian folktale collections of Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, with their stories of trolls and talking animals.

“The Parsonage” by Nikolai Astrup, no date. Oil on canvas. Savings Bank Foundation DNB / KODE Art Museums and Composer Homes, Bergen.

Initially, he traveled to Kristiania (now Oslo), and studied with Paris-trained Harriet Backer; a seven-month sojourn in Germany and Paris in 1901-02 followed, where he encountered works by Arnold Böcklin, a Swiss artist who was inhabiting his landscapes and seascapes with mythical creatures, and Henri Rousseau, whose work he greatly admired.

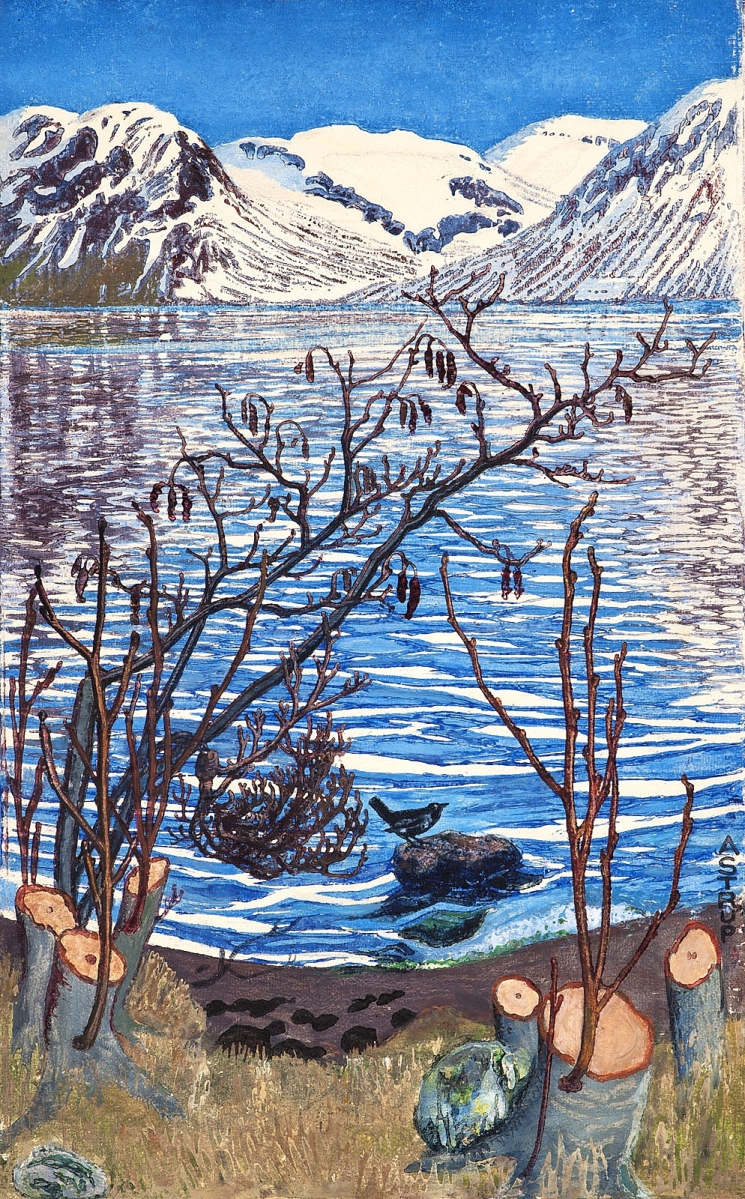

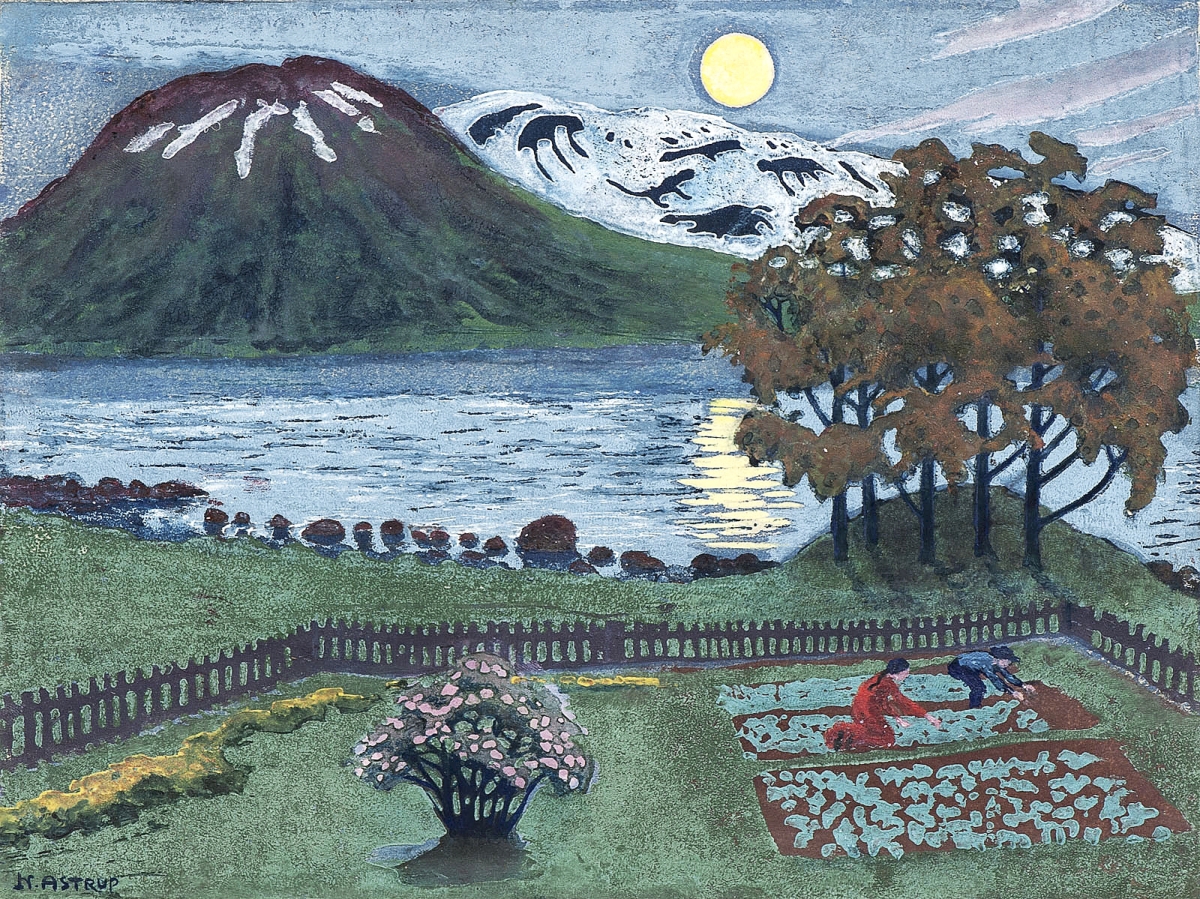

But foremost, however, he was captivated by the Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints that he encountered while studying in Paris. He set about to teach himself the carving process and to study and copy several works in precise detail. Over time he developed a labor-intensive and idiosyncratic process to produce hybrid works that combined elements of ukiyo-e, traditional color woodcuts, hand-colored prints and monotype.

Through hand-carving, and his meticulous use of oil paint inks, he was able to alter the composition and the atmosphere radically as he moved from print to print. These variations, in turn, enabled the viewer to experience the landscape as he had – in its many iterations. Between 1904 and 1923 he would execute 52 of these prints.

Astrup defied expectations early on in his decision not to settle in Kristiania, the artistic capital of Norway, but to return to Jølster in 1902. But, after mixed reviews of his third solo exhibition in February 1911, Astrup left Jølster for a sojourn in Berlin, determined to reinvent himself. It was at this time, guest curator MaryAnne Stevens notes in the exhibition’s accompanying catalog, that the artist absorbed the latest developments in European art and was exposed to Russian avant-garde theater.

“Interior Still Life: Living Room at Sandalstrand” by Nikolai Astrup, 1926-27. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

“As a result of these experiences, Astrup’s work would become increasingly ambitious in scale and technical complexity, his paintings and prints moving away from naturalism to include multi-perspectival viewpoints, simplified forms and an intense, heightened palette,” she writes.

When he returned home, he and his family settled on a steep, north-facing property that he would transform into an artist garden on the order of Claude Monet’s Giverny. Over the next decade he terraced plots on the steep hillsides to raise vegetables and cultivated fruit trees. And the couple acquired several historic wooden buildings with turf roofs that would form a hub for what became a family of 11.

His wife, Engel, was a talented textile artist and theirs was an aesthetic partnership. In several paintings her dresses and other textile designs are featured. In one painting of their living room, the traditional regional tablecloth and woven bench speak to the couple’s interests in preserving local craft and culture. Rhubarb was a family specialty, with many varieties grown each year – providing more than enough ingredients for Astrup’s rhubarb wine.

Through the imaginative installation at the Clark there are two immersive stops – one injects a visitor into a photo montage of the landscape surrounding Lake Jølster, while another places the visitor on a path connecting the farm’s constellation of buildings. The stations seem to signal to visitors that they are about to become immersed in the artist’s natural and sculpted worlds.

The Clark’s curatorial team, which includes Lipp chief curator Esther Bell, curatorial research associate Alexis Goodin, and Marx director of exhibitions Kathleen Morris, worked closely with Stevens, an independent scholar and the former director of academic affairs at the Royal Academy, London, on these and other aspects of the installation.

In Astrup’s imagined world, a pollarded willow tree morphs into a goblin or troll, while grain stacks appear as human figures. A snow-covered mountain is transformed into the Ice Queen, a reclining female nude. And there are rhubarb plants that dwarf the family that is cultivating them.

His beloved, but endangered, marsh marigolds feature repeatedly in his landscapes, and their destruction as the result of agricultural practices fueled his efforts as a conservationist. “Marsh Marigold Night,” circa 1915, a woodcut with hand-coloring on paper, is among the most luminous and textured woodcuts of his production, Stevens writes, with different layers and perspectives that stretch from the foreground to the farm buildings and on to the mountains and sky, all made with distinct colors and forms.

“Night Light, Rhubarb, Goose and Bird Cherry Tree” by Nikolai Astrup, circa 1927. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

In his series titled “Foxgloves,” curatorial research associate Alexis Goodin notes, one sees the interplay between media that characterizes Astrup’s production: an oil painting from 1909 preceded the carving of woodblock, which were made between 1915 and 1920, for a large-scale print of a slightly different composition.

Childhood memories, and meticulous records compiled in notebooks, remained essential tools for his practice. Astrup’s mission remained deeply personal, in that it was part-dream, part-vision and part-lived experience, Stevens writes.

So, too, in his vivid writing, we find an artist/poet painting this scene: “And on Midsummer’s Eve – when bonfires were lit on all the mountains and people swarmed like black dots up the slopes, and the girls were dressed in red with white blouses and stood like points of light sparkling about the flames – it was sinful for Christians to join the celebration,” he writes. “I had to stand back behind the fence and look and listen while the others danced around the bonfire and whooped for joy.”

But art has given Astrup the means by which to cast off the shackles of his repressive upbringing. As he conjures Midsummer’s Eve celebrations, bonfires can be seen up close and in the distance, seemingly engaged in an erotic call and response. In the foreground couples swirl and dance to the strains of the hardanger fiddle. Norway’s national instrument triumphantly fills the night air.

The Clark Art Institute is at 225 South Street. For more information, www.clarkart.edu or 413-458-2303.

.jpg)

.jpg)