By Rob Hoffman

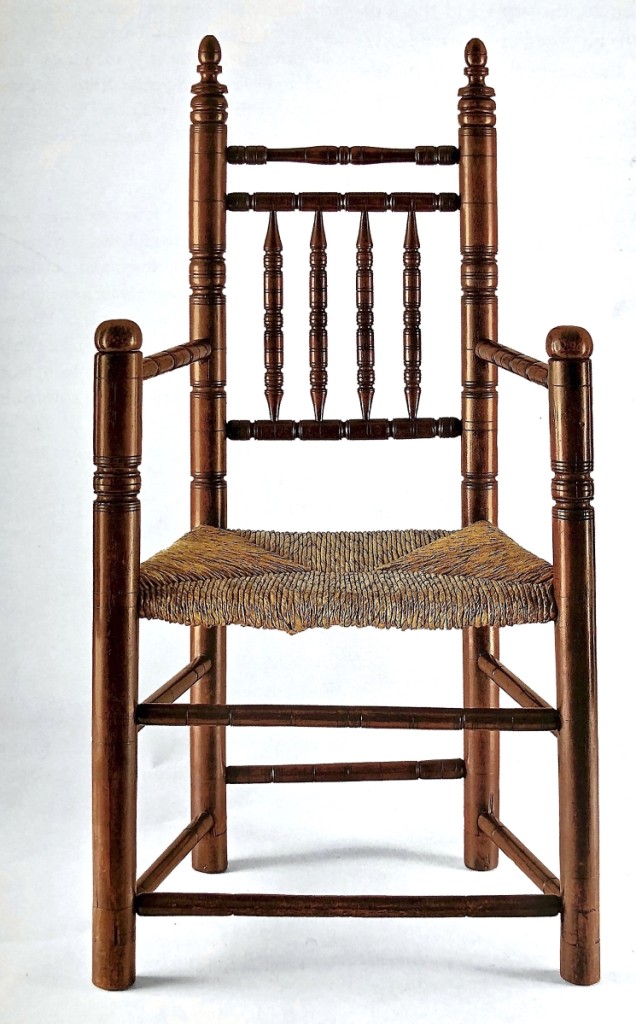

The maple armchair shown in Figure 1 had dwelled for some 50 years in the collection of the late Marion and Theodore Gore, Williamsburg, Va., prior to its consignment into Brunk Auctions’ (Asheville, N.C.) Premier sale of March 23, 2019. The Brunk catalog had identified this as an early “Great” chair – terminology that connotes seating furniture of massive proportions and imperious character (i.e. armchairs with chutzpah). Such pieces were rare even during the Seventeenth Century and are thought to have been consigned exclusively for use by people of high status and prestige. To quote John Kirk in his 1977 The Impecunious Collector’s Guide to American Antiques, “When you sit in the chair and put your hands on these handholds you get a proper sense of being in command of the space around you. Such chairs were reserved for the most important people, while others sat on stools and benches.”

The longstanding tradition among American collectors is to brand specimens of this vintage and character as “Pilgrim Period” (circa 1620-1720) and of the “Carver” variety (via fictive association with Plymouth Colony Governor John Carver, 1576-1621).

Figure 2: Bolles Spindle-back Carver-type Great Chair. Photo courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Early collector’s romantic nomenclature for spindle-back chairs distinguished two varieties: the “Carver” type, having spindles above the seat versus “Brewster” type, with spindles both above and below the seat. The latter term derived from association with Plymouth Colony senior elder William Brewster (1566-1644).

This terminology was popularized a century ago by venerable American pioneer-collectors such as Wallace Nutting and Luke Vincent Lockwood. The updated nomenclature for Seventeenth to early Eighteenth Century seating furniture is less romantic. Chairs of this variety are now called “spindle-backs.” I hope readers will not be offended if I were to perpetuate the antediluvian. “Carver” is less arid and maybe the antiques world could use a little more romance and a bit less pedagogy.

Theodore Gore and wife Marion had devoted more than 50 years to collecting art and antiques. Theodore Gore was a newspaper editor. Judging from pieces in the Brunk sale, it is clear that the Gores had a great affinity for Seventeenth Century pieces, though mostly of English and Continental manufacture. The Gore chair was among the few American pieces in the collection.

While early Carver chairs of any variety are relatively rare, the less spirited specimens (post Seventeenth Century) do crop up with some regularity. On the other hand, the bolder and more dynamic earlier examples such as the Gore chair are rarely seen outside of museums or historical society collections. Thus, ascertaining comparable references to the Gore chair was simply a matter of browsing among published specimens whose sum total is possibly fewer than 100 examples.

The chair shown in Figure 2 was bequeathed to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1909 as part of the Bolles collection.

Eugene Bolles was a Boston lawyer who had established a substantial collection of “Pilgrim Period” and other furniture during the late Nineteenth Century.

This chair (Figure 5, Met accession number 10.125.207) is also referenced as “Spindle-back Armchair” in Frances G Safford’s 2007 American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art., Vol. I, Early Colonial Period: The Seventeenth Century and William and Mary Styles and stated to be circa 1650-1700, from Eastern Massachusetts with Boston influence.

Figure 5: Bolles Spindle-back Carver-type Great Chair as acquired in 1909. Photo courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Even a cursory comparison of the size, proportions, material and especially the details of turnings between the Gore and Bolles chairs reveals an unlikely contingent act of fate – namely, that these two chairs are somewhat akin to a pair of 350 year old twins separated at birth. These pieces are not merely of the same “school” but were unquestionably made by the same person in the same shop using the same lathe, gouges, scribes and calipers. What is the degree of singularity and probability of such an event? Hold that thought momentarily as we review Safford’s keen observations.

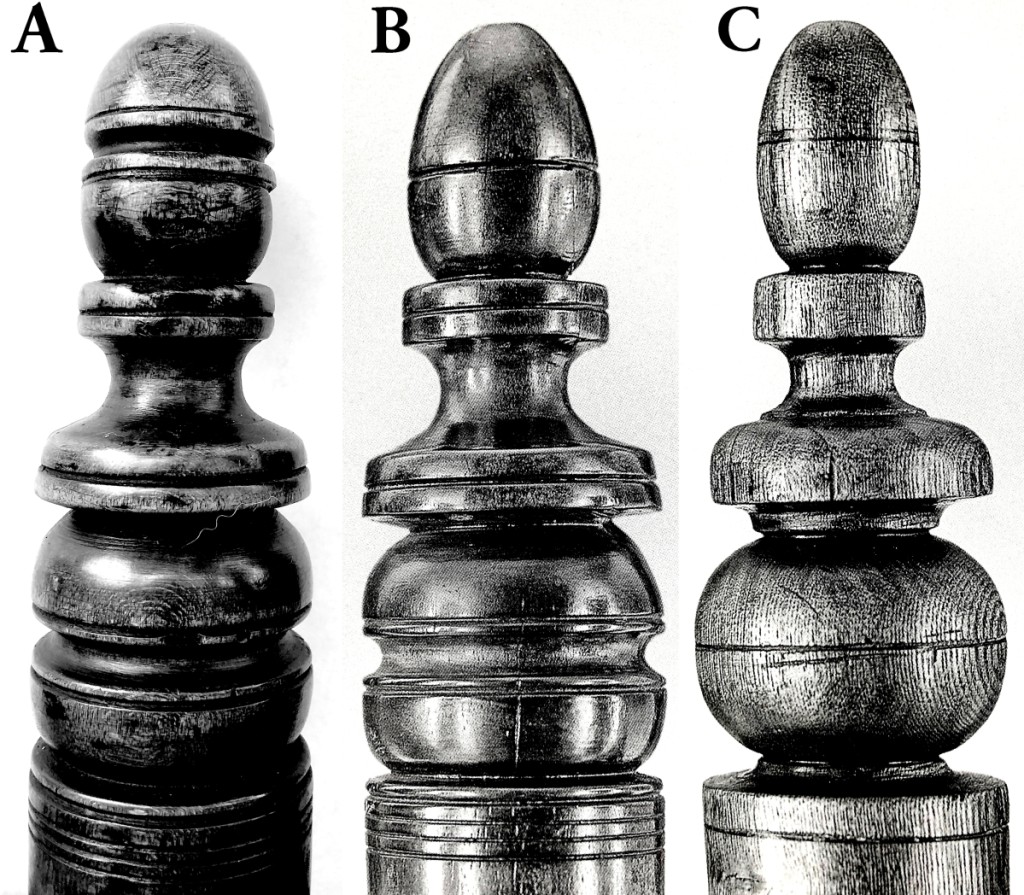

Perhaps the most diagnostic feature of any turned chair is the finials, as much a signature of the chairmaker as the scroll of a Cremonese violin. The Bolles and Gore chair finials bely a generic Eastern Massachusetts regional archetype known as the Boston style “urn-and-flame.” Note in Figure 3c that the lower portion of the “urn” is actually comprised of a compressed ball. A feature that distinguishes both the Bolles and Gore chairs from other Eastern Massachusetts finials was the maker’s trademark habit of bisecting the compressed ball with a half-round groove (i.e. “reel”) rather than a simple score mark typical of most Boston-type finials. Contrasting the various examples in Figure 3, a subtle but significant difference emerges between the Bolles and Gore finials. In the case of the Gore chair the maker reiterated a smaller version of the half-round groove in the upper flame portion of the finial.

If we want to be picky, we might say this warrants likening these chairs to twins of the fraternal rather than identical variety. Otherwise, nearly every other feature of both chairs are virtually indistinguishable, especially the unique complex turning patterns of the back spindles. Both chairs are maple with posts precisely 2¼ inches in diameter at their tops; both chair’s posts narrow slightly toward the floor; and finally, both chairs are characterized as having a greater quantity and complexity of score marks than ordinarily found on Boston/Eastern Massachusetts Pilgrim Period chairs.

Figure 3: Urn-and-flame finials. A: Gore Chair finial; B: Bolles Chair finial; C: example of generic Boston-type finial.

Safford, like any good researcher, also sought to find comparative examples. Miraculously, she found one. This was a needle in a haystack and how she pulled it off I cannot say.

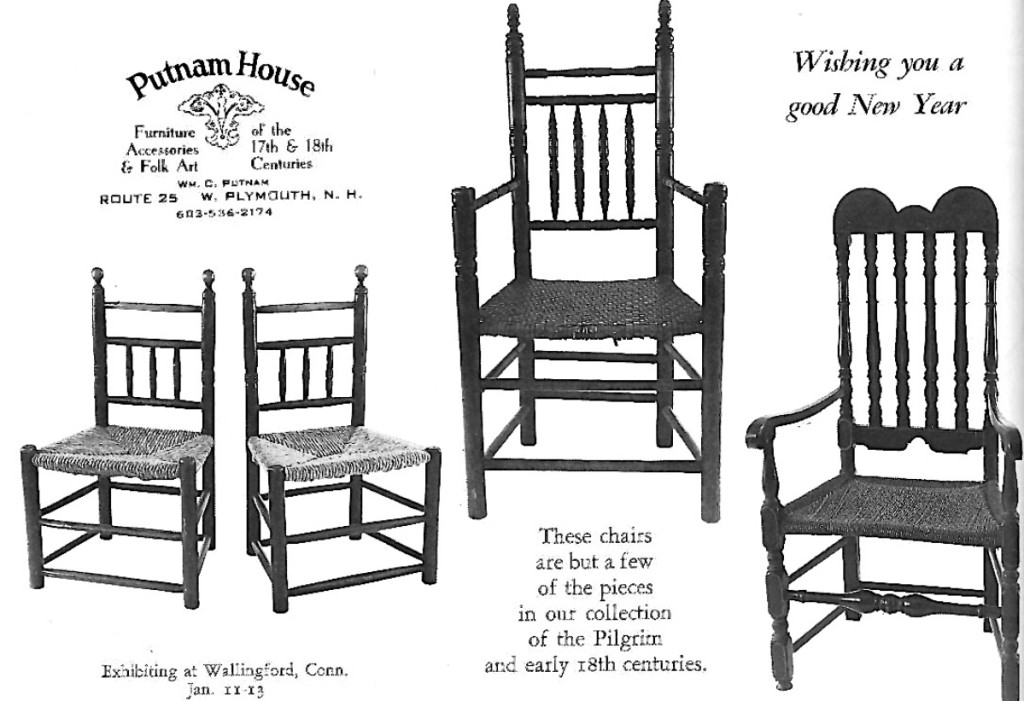

In her own words: “A chair advertised in Antiques (magazine) in 1967 is the only other piece published that has like idiosyncratic turnings.”

Safford’s amazing comparative specimen discovery presents two hypotheses: either there are two extant 350-year-old Carver chairs by the same maker or there are three. Obviously, the way to ascertain the truth was to find the 1967 Antiques ad.

I am indebted to my friend and Winterthur curmudgeon Brock Jobe for providing access to Figure 4 – the Antiques ad to which Safford referred. Alas, the two-chair hypothesis is confirmed. The 1967 Antiques ad chair and the Gore chair are one and the same. At some time after the ad was published, someone (perhaps the Gores) had swapped the splint seat for a more appropriate rush seat. Otherwise it is empirically the exact same chair.

In describing the Antiques chair (Q.E.D., Gore chair) Safford observed, “Those hand grips are in keeping with the overall decorative scheme, in contrast to the replaced pommels on this (the Bolles) chair.”

Consider Figure 5. This is a Met archive photo of how the Bolles chair appeared when initially donated to the museum. By present day standards many collectors would prefer the “before” to the “after” picture. At some point in its Met tenure, the feet and pommels were restored by “piecing” (i.e. grafting). In addition, the original dry finish and patina of the chair that Bolles had known and loved had been exchanged for something more vanilla with a sugar-coated membrane. Such was the inconsonant history of the evolution of American museum conservation theory. Kirk’s 1977 maxim “buy it ratty and leave it alone” has not always been the gold standard for scholars and curators. But in light of the fact that so many of these old chairs have been substantially altered over time, it does raise the question about the integrity of the Gore chair. The Brunk cataloger did acknowledge that the feet had been pieced. I might add, in such an expert manner that the graft joints are barely visible. The restorer had meticulously matched the pieced extensions to precisely fit into the rocker slots.

But what about the handholds on this chair? With only the benefit of a 40-year-old black and white magazine ad, Safford proffered that the pommels were “of appropriate character.” As the actual chair is now accessible after a half-century hermitage, other means are available. Examination of the pommels in Figure 1 suggest via the quality of maple, color, patina and wear patterns that these are original factory parts. However, as savvy antiques people who have dealt with a lot of old New England furniture will attest, those anonymous Yankee carpenters from back in the day could be skillful and clever.

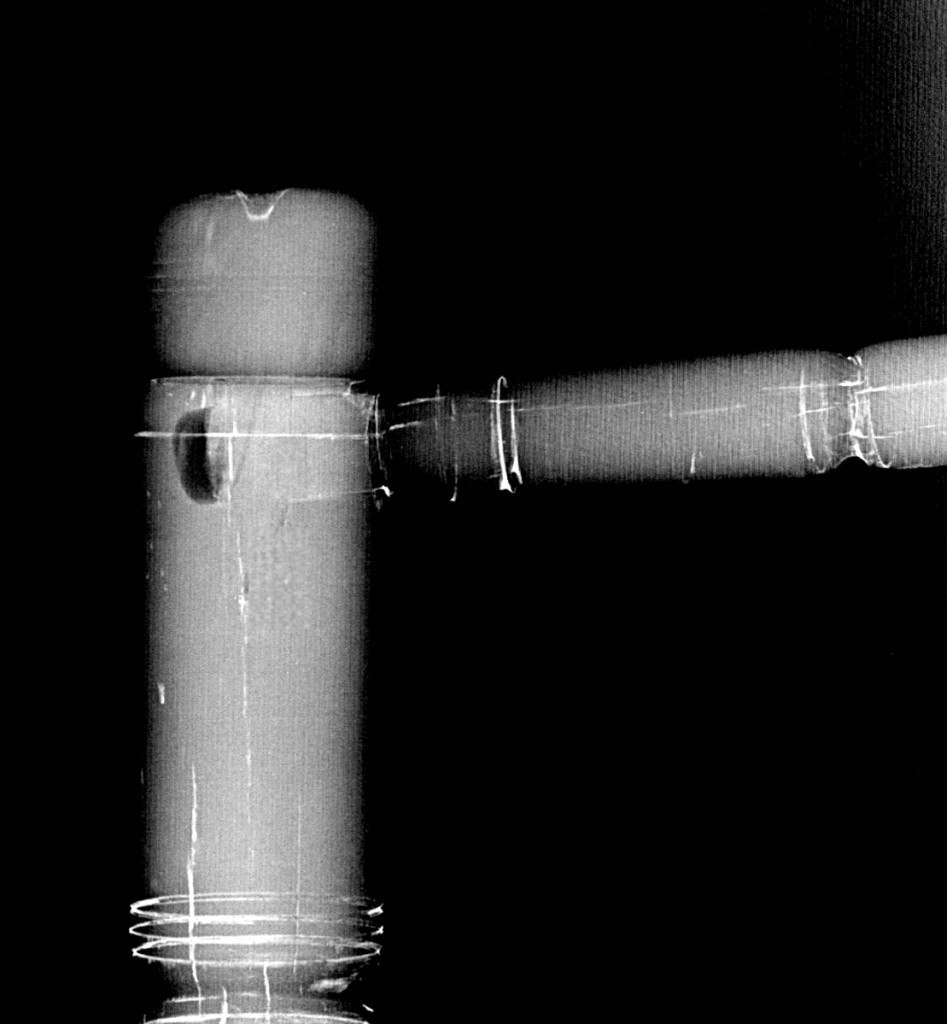

Consider Figure 6, a radiograph of the vicinity of the right-hand post of the Gore chair. The chair had remnants of black paint which probably contained metallic ingredients. This accounts for X-ray image illuminating white lines wherever there were score marks, cracks or fissures which trapped old paint. While the radiograph revealed no evidence of any sort of foreign intrusion from the pommel into the vertical post, we can clearly see the intrusion of the horizontal arm spindle. Note especially, the dark spot at the terminus of the auger hole used to mount the spindle into the post. This is what the profile of an ancient drill hole looks like from the days before the advent of gimlet bits. It seems safe to advise that if the Met ever wanted to perform a redux on the Bolles chair pommel repair they could comfortably use the Gore chair as a template.

Let us now return to the point where I had stated “hold that thought.” How can two ancient handmade chairs, even if made by the same person, share so many fine points of craftsmanship and detail, including the precise arrangement of dozens of scribe marks? Such are the hallmarks of modern mass-produced factory-made objects rather than preindustrial antiques. The answer is that even vernacular craftsmen used tools and techniques that would actuate uniformity and redundancy. Benno Forman in his 1988 American Seating Furniture 1630-1730 discussed various turner’s devices including a tool called a chairmaker’s marking stick – essentially, a wooden rod studded with sharp metal points at various intervals. A similar sort of template tool was almost certainly used by the maker of the Bolles and Gore chairs to facilitate the near-perfect uniformity of complex scribe marks that embellish these posts and spindles.

As noted, Safford summarized the turnings of the Bolles and Gore chairs as “idiosyncratic.” Though if assessed on the basis of aesthetic merit, we might say these chairs are florid, dramatic, original and creative. Clearly, the Seventeenth Century Massachusetts craftsman who made these objects had ne plus turner talent and it is a good bet that these two chairs were not his first rodeo. This person was a professional. He made chairs and perhaps other types of furniture and probably sold these things to support himself and his family. We can only guess as to how many chairs he might have produced. Perhaps dozens; perhaps more; or maybe less. We will never know for sure. In time we may see other chairs by this maker surface from private collections. On the other hand, these may be the only two extant examples on the planet.

In conclusion, consider a final observation in comparing similarities of the Bolles and Gore chairs – an observation of a forensic nature. Note – both chairs were altered to accommodate rockers; both in the exact same manner, via slotted mortices. Such was the earliest perturbation of American rocking chairs, circa 1790-1800. So-called “rockerization” was a common practice for refurbishing and resuscitating old-fashioned and outdated chairs. While spindle-back great chairs may, as Kirk stated, give one a sense of “being in command,” they don’t exactly cradle or pamper the human lumbar. As symbols of status, early great chairs may have been designed and engineered more for the visual impact to the onlooker rather than the comfort of the sitter. The seats of these chairs are shallow and the multitude of complex spindles, albeit crisp and beautiful, become fairly ruthless with extended use. Perhaps there’s a bit of an anatomical reprieve in the ability of “rockerization” to facilitate comfort by allowing modest reclining. But the fact is that even by the mid-Eighteenth Century there were more ergonomic options available to American chair shoppers. One might view “rockerization” as the terminal stage in a chair’s voyage en route to becoming fireplace kindling. Taking into account cultural and stylistic evolution along with other vagaries (human as well as natural), it is perhaps something of a miracle that any of these things survived even long enough to suffer the indignation.

So what are the odds that two nearly identical Pilgrim Period Carver chairs by the same maker could survive more than three centuries to make it to the year 2019? This is a trick question, of course. The odds are exactly 100 percent. The odds of finding others? Definitely a long shot.

Acknowledgements: The author is indebted to the following individuals and institutions for their cooperation and assistance in supporting this manuscript. Thanks to Michele Parparian and Brunk Auctions for kindly sharing information and photos of the Gore Chair. Kudos, as well to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s CCO program which allows researchers to freely access and use their public domain information including the various images of the Bolles chair. Finally, thanks to Brock Jobe, Steve Arsenault, Robert Morrissey (Morrissey Antiques, St Louis) and others who were kind enough to take the time to review this manuscript and share their comments.

-575x1024.jpg)