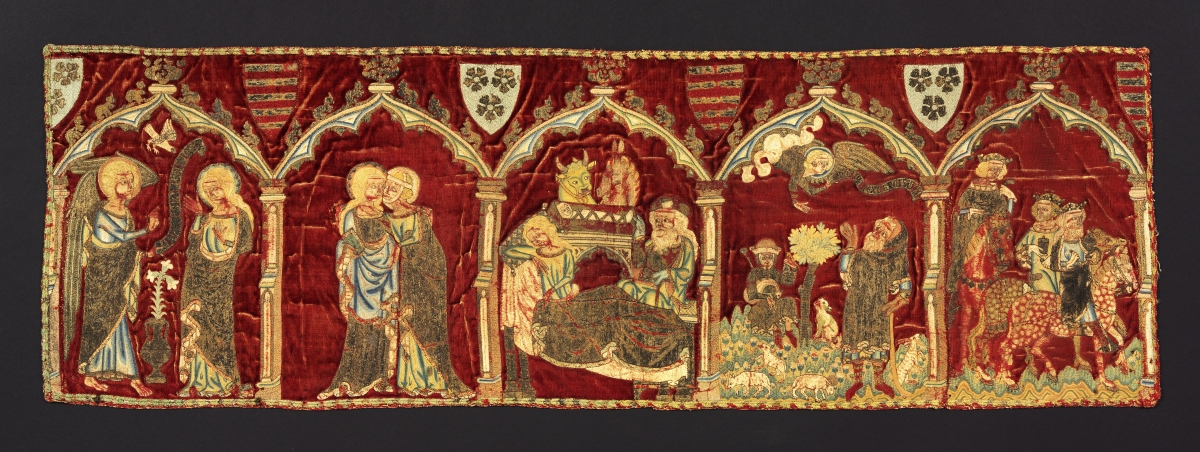

“The Life of The Virgin,” detail from an embroidery, possibly for an alb or liturgical vestment, 1320–40. Silk velvet, embroidered with silver-gilt, silver and silk thread. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

By Karla Klein Albertson

LONDON – “Opus Anglicanum: Masterpieces of English Medieval Embroidery,” through February 5 at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, brings together the most impressive gathering of early English needlework ever assembled for display. More than 100 rare and fragile works dating from the Twelfth to Fifteenth Centuries are carefully arrayed to allow a closer view of the embroidery’s incredible detail. Many pieces are drawn from the museum’s renowned collection of textiles, while others are returning to England for the first time since their creation roughly 700 years ago.

“English work,” or opus anglicanum in the Latin that was common speech throughout the Catholic world, was an exquisite, painstaking and highly prized style of needlework. The gold, silver and silk threads used to compose the embroidery were an expression of enormous wealth. This was an era when the church dressed to impress and the earthly princes of the secular court were rivals in splendor. In addition to ecclesiastical and secular garments, embroiderers decorated elaborate altar furnishings and precious hangings that softened the edges of public and private rooms.

“As a historian, the opportunity to see all these objects, normally scattered across museums and cathedral treasuries in Europe and North America, together in one place is thrilling, and a privilege we are unlikely to have again,” notes Glyn Davies, the V&A’s curator of medieval art and a co-organizer of the show.

“Everyone we approached expressed a willingness to work with us on the exhibition, but some pieces were simply too fragile to travel. We do think that what we brought to London – and the possibility of seeing pieces side-by-side – makes a huge difference to the appreciation of this type of work. And this has been a wonderful opportunity for us to revisit our own treasures,” says Clare Browne, the museum’s curator of textiles. While several exhibits were drawn from displays in the V&A’s Medieval Galleries, more than 40 others came out of storage for the first time in many years.

To Browne’s delight, the public has embraced the show. She notes, “One of the particular things we were very keen on was enabling people to be close enough to really see the embroidery. You can get much closer than in a cathedral or treasury setting, and that’s been really well received by visitors. We’ve been able to explain more. So even pieces that people may have known before are a revelation when they are displayed in this way.”

At first glance, the exhibition makes it appear that most of this magnificent needlework was made for ecclesiastical purposes. Browne stresses, “Certainly there would have been just as much made for the court, but the pieces that didn’t have an ecclesiastical context were much more liable to be recycled, reused, passed down the chain of ownership from the elites to the less elite. Few have survived. The ecclesiastical pieces have been venerated because of their association with the church. Some work would have been done in convents and monastic institutions, but most of the pieces in our exhibition would have been done in professional workshops by people who were paid as part of a highly-skilled trade.”

In an accompanying catalog, Davies, in her chapter on “Embroiderers and the Embroidery Trade,” discusses documentary evidence from the Thirteenth to Fifteenth Centuries that refers to English embroiderers and their output. References turn up in royal records, legal documents and surviving letters. Although it remains impossible to assign surviving examples to particular workers, the references do describe what type of work was available, as well as how the trade worked, and at times cite the names of individual embroiderers. The center of the trade was in London, as might be expected, but documents make it clear that there were lesser workshops beyond the metropolis. Both men and women were praised as skillful professional embroiderers. Larger projects would have occupied workshops for months or years at a time.

Davies writes, “The organization of the textile trades in medieval London was complex. The most powerful figures were the merchants known as mercers. The mercers specialized in selling cloth of all sorts, as well as goods made from them, and came to control a whole class of subordinate cloth-working trades within London. … The greatest mercers also had access to the elite clientele who could afford the luxury embroideries… By the latter part of the thirteenth century, the influence of the mercers within England’s textile trade had greatly increased. While, in the earlier part of the century, the King’s Wardrobe regularly acquired luxury goods at regional fairs, by the later thirteenth century these were supplied directly to the Wardrobe stores in the City of London by London merchants.”

Center, the Vatican Cope, 1280–1300, presented by Pope Pius X to the Musei Vaticani in 1910, is made of red silk twill embroidered with scenes of Christ, the Virgin Mary, disciples and saints. Extreme left, the cross-shaped Marnhull Orphrey, a fortunate survivor of the Reformation purchased by the V&A in 1935 from the Roman Catholic Presbytery of Marnhull in Dorset, is embroidered with scenes from Christ’s Passion that resemble miniatures on an early Fourteenth Century psalter. The marquee above the exhibits lists names of English embroiderers recorded in period documents.

The demand for luxury goods at court was so great that dedicated workshops may have been created within the palace complex to fulfill orders for garments, diplomatic gifts and royal draperies. A reference from 1303 refers by name to two women who filled an order for 2,800 fleurs-de-lis and heraldic lions on textiles for the Queen’s Chambers. Queen Eleanor of Castile (1241-1290), who was married to King Edward I, commissioned English embroidery to be sent as gifts to her brothers in Spain.

Of needlework patronage, Julian Gardner writes that appreciation of English embroidery in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries was international, with patrons from Scandinavia to Portugal. One of Clare Browne’s favorite pieces is from the remarkable Hólar Vestments, stitched with images of local saints for a cathedral in Iceland and on loan from the National Museum there. An early Icelandic traveler apparently saw examples of English work and put forward a special commission for similar pieces with appropriate regional themes. The martyred English saint Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 to 1170, is among the rich and powerful who commissioned or owned English embroidery. In addition to an embroidered vestment associated with him, there are later works that refer to the Becket cult that arose after his murder.

Standing only inches away from the opus anglicanum stitching, visitors may ask themselves how such spectacular effects were achieved. Tricia Wilson Nguyen, a featured speaker at the Winterthur Needlework Conference in October, has a unique perspective. She says, “I’m a materials scientist and an engineer as well as an embroidery teacher, so I look at this from two different angles. What they did had to do with the materials themselves. Often in embroidery or other art mediums, the material itself enables or does not enable techniques.”

Making gold thread was a complicated process, Wilson Nguyen explains. “People had to figure out ways to marry gold with something else so that it was durable going in and out of the fabric or couched onto the fabric…. Primarily three stitching techniques were used in the opus anglicanum. By doing them densely together, they raised the art to a new level.”

Dating to circa 1400, the “Dunstable Swan Jewel” was probably made in France and was found in 1965 at Dunstable Friary in Bedfordshire. It was worn as a brooch or as a necklace. The British Museum, London

The expert continues, “They did a ‘split stitch’ with silk thread. You make a very short stitch with the needle on top of fabric – an eighth or 16th of an inch or even smaller. The finer you do it, the more you can have nice, even curves and lines. Then there’s the gold – usually used as a background – which was worked in two different ways. One is called ‘underside couching,’ in which you take the gold thread and lay it on the surface of the fabric. You use a silk thread to come up through the fabric and go over the gold thread, but you make sure you take your needle back through the hole you just came up in – not easy to do. This was an innovation of opus anglicanum. You have gold all over the place, but the fabric has more suppleness. It is wearable and more drapable.

“The third technique they used was regular ‘surface couching.’ They couched it down with a silk thread, but this time did not mask the hole, so the silk thread could be seen on top of the gold thread on the surface of the fabric…. You could differentiate between different areas this way. To take that to the extreme, near the end of the period they switched over to the technique of ‘or nué’ where you were stacking those couching stitches right next to each other, so you actually obscure the gold.” A needle artist, says Nguyen Wilson, could “basically stitch a picture on top of a gold thread.”

Linda Eaton, John L. and Marjorie P. McGraw director of collections and senior curator of textiles at Winterthur, paid this tribute to the V&A’s groundbreaking exhibition: “The material that they have on view is just incredible. They were able to borrow such rare things – things you just never see – so this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

“One of the things that’s hard to understand now is how glittery and blingy it was in its time,” she continued. “The colors have faded and the velvets have worn, but we should be in such good condition when we’re 600 or 700 years old! It’s still beautiful now, but you can just imagine what it would have been like when it was new – just the richness of it all.”

The exhibition is accompanied by the definitive new publication English Medieval Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum. Edited by Clare Browne, Glyn Davies and M.A. Michael, and co-published by the V&A and Yale University Press, the book surveys the cultural milieu from which the embroidery style arose and offers an invaluable guide to the materials, techniques, imagery and history of each piece displayed.

The Victoria and Albert Museum is on Cromwell Road. For more information, www.vam.ac.uk.

Journalist Karla Klein Albertson writes about decorative arts and design.