By Laura Beach

PADUCAH, KY. – Women, activism and the needle have long been associated in the public imagination, from the much embroidered story of Betsy Ross and the American flag, to today’s “sewing angels,” at work making masks for our healthcare heroes.

Of all the needle arts, quilting, at times a communal activity, may have the deepest ties to women’s social action. As fiber artist, author and curator Susanne Miller Jones sees it, “Women love the feel of thread and fabric in their hands. It is a very natural medium for us. When women discovered they could do more with fabric than just sew straight lines or make clothes, it unleashed creativity. The field of quilting is now wide open, as imaginative as the women who are drawn to it.”

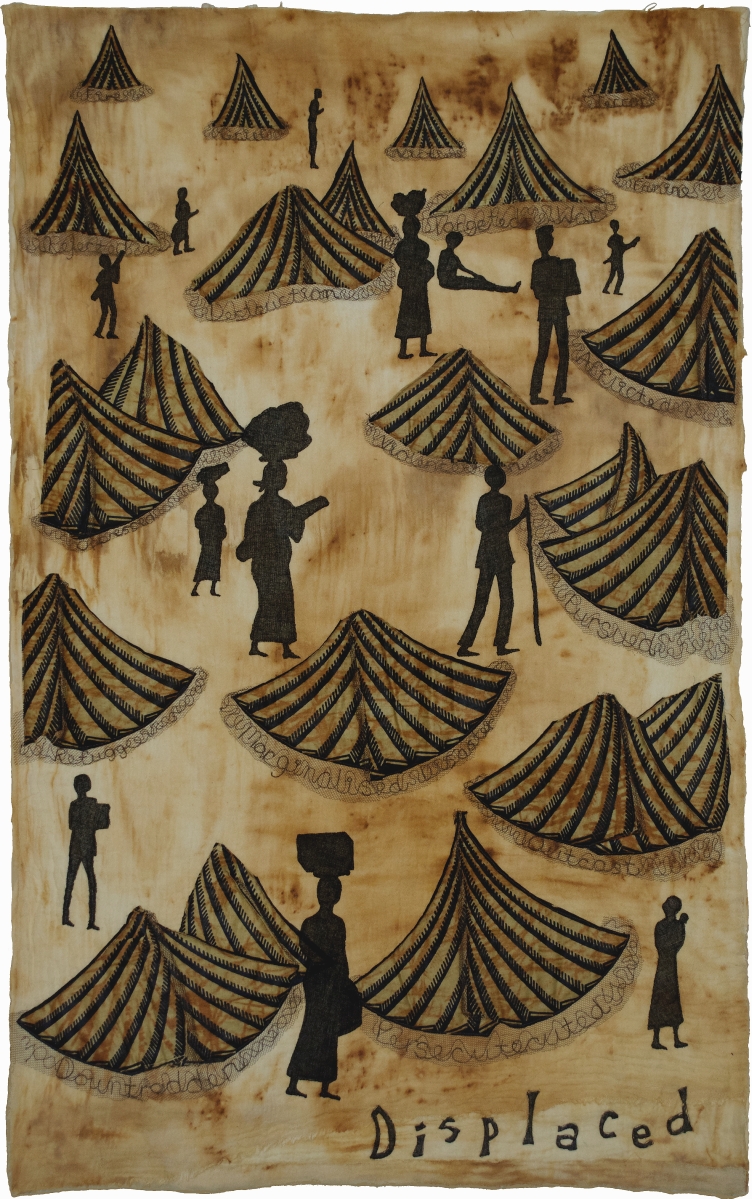

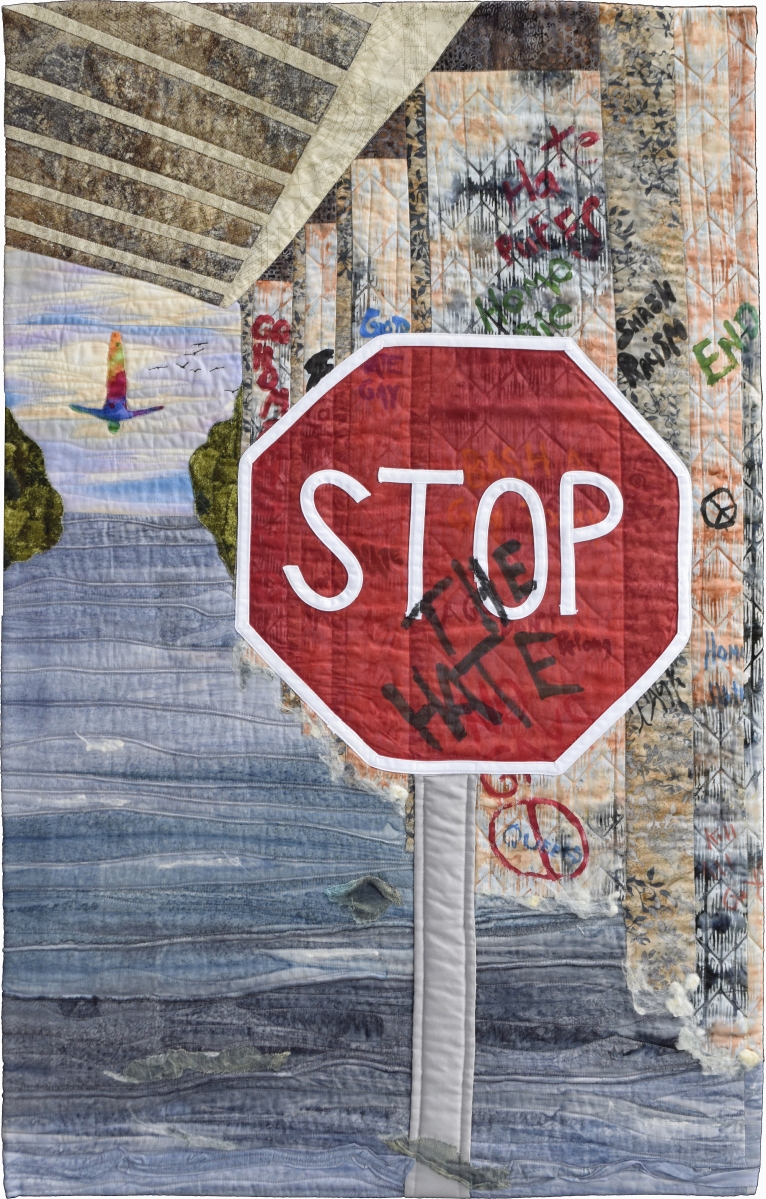

Disturbed by the erosion of civil rights in the United States and abroad, but inspired by stories of personal courage and collective progress, Jones on January 20, 2017 put out what quilters – not all women, of course – know as a “call,” inviting needle artists to submit work on the theme of social justice for possible inclusion in a juried show she hoped to organize. The result is “OURstory: Human Rights Stories in Fabric,” continuing at the National Quilt Museum, a leading center for contemporary quilting in a city famous for fiber art, through September 8.

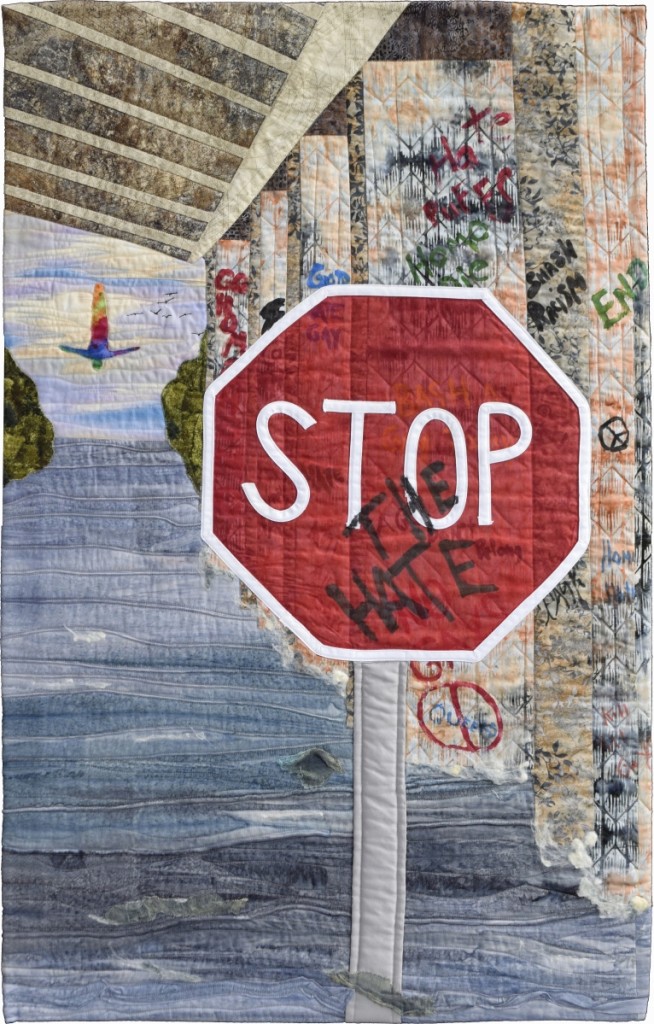

The museum had no way of knowing how timely “OURstory” would be, what with the international unrest unleased by the May 25 death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police and the US Supreme Court’s landmark June 15 decision upholding protections for LGBTQ citizens. “OURstory”‘s rejection of discrimination and injustice of all kinds, from the disastrous consequences of environmental degradation to what some see as intolerance for conservative religious beliefs, puts “OURstory” squarely within the current debate.

The conversation is one Frank Bennett, chief executive officer of the National Quilt Museum, is happy to have. “While the timing of the show is serendipitous, these topics have become very mainstream. I want everyone to see ‘OURstory’ because it offers all kinds of perspectives that may differ from one’s personal experiences. Each quilt is a story about an individual’s experience with human rights. We hope the show will cause meaningful conversations that are healing for everybody.”

Bennett was living in Dallas and working as a consultant when he was approached about a project for the National Quilt Museum, whose top post he assumed in 2011. Among his first questions were “Where is Paducah and can I fly there?” The expert in marketing and strategic planning soon came to know the bustling community as a location named by UNESCO in 2013 as an official Creative City, one of nine so-designated places in the United States. Paducah is home to both the National Quilt Museum, which opened in 1991, and Quilt Week, organized by the American Quilters Society (AQS). Quilt Week is generally mounted in late April and attracts roughly 30,000 visitors annually. Bennett regards the National Quilt Museum as a hub of a city alive with galleries, studios and other artistic enterprises.

“OURstory” is the third major traveling exhibition organized by Jones, who, encouraged by her grandmother, began stitching as a girl. The curator took up quilting in 2010, a year before she retired as a schoolteacher in suburban Washington, DC. She learned the basics of quilting from her good friend Lisa Ellis, chairperson of Sacred Threads, an acclaimed biennial exhibition in Herndon, Va., that showcases quilts on themes of joy, peace and brotherhood, spirituality, inspiration, healing and grief. Through these initial encounters with the medium, Jones, now on Sacred Threads’ organizational committee, discovered the broader community of makers, which unites its members through guild meetings, retreats and shows.

“I expected I would be a traditional quilter, making baby quilts and that sort of thing,” says Jones, who, like other “OURstory” exhibitors, regards herself an art quilter. The Studio Art Quilt Associates define an art quilt as “a creative visual work that is layered and stitched or that references this form of stitched, layered structure.” Each art quilt is unique, and, unlike many traditional quilts, not derived from a pattern.

As Bennett sees it, his institution is “a contemporary art museum that presents the work of today’s top quilt and fiber artists. Modern quilters are artists at the same level as artists who work in other mediums. I want everyone to see their work in person because if you see it you will agree.”

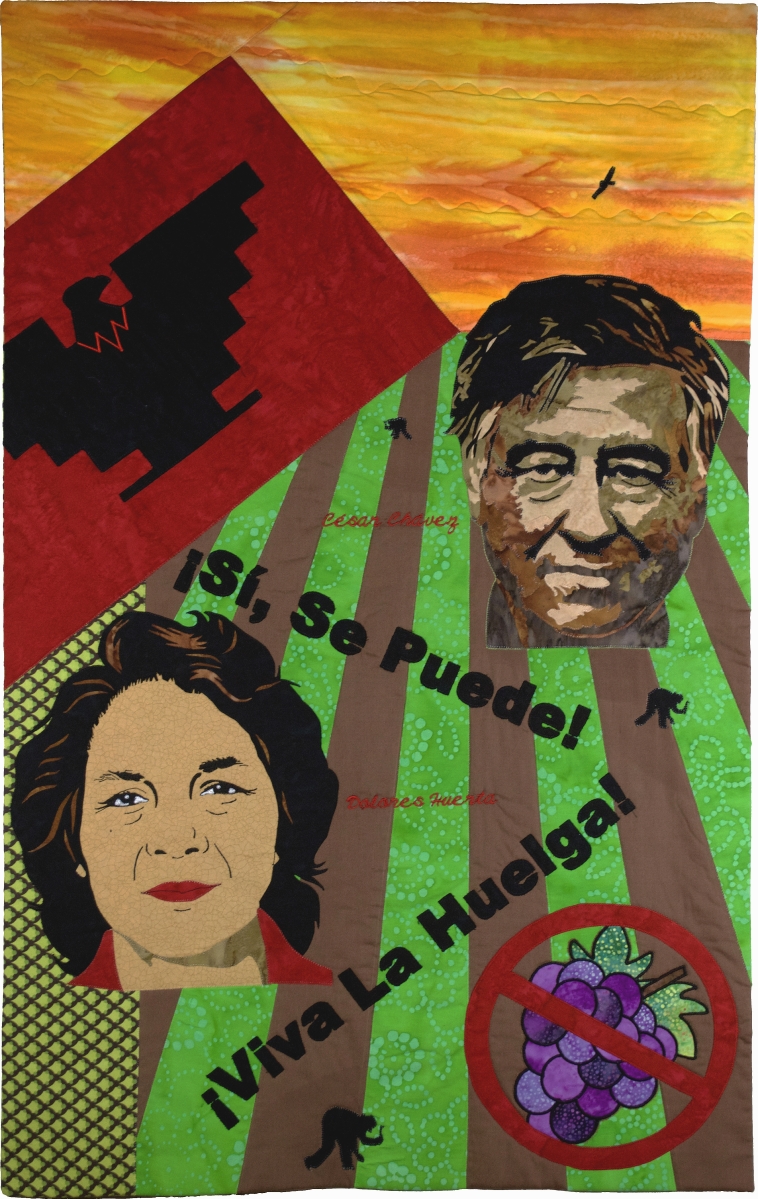

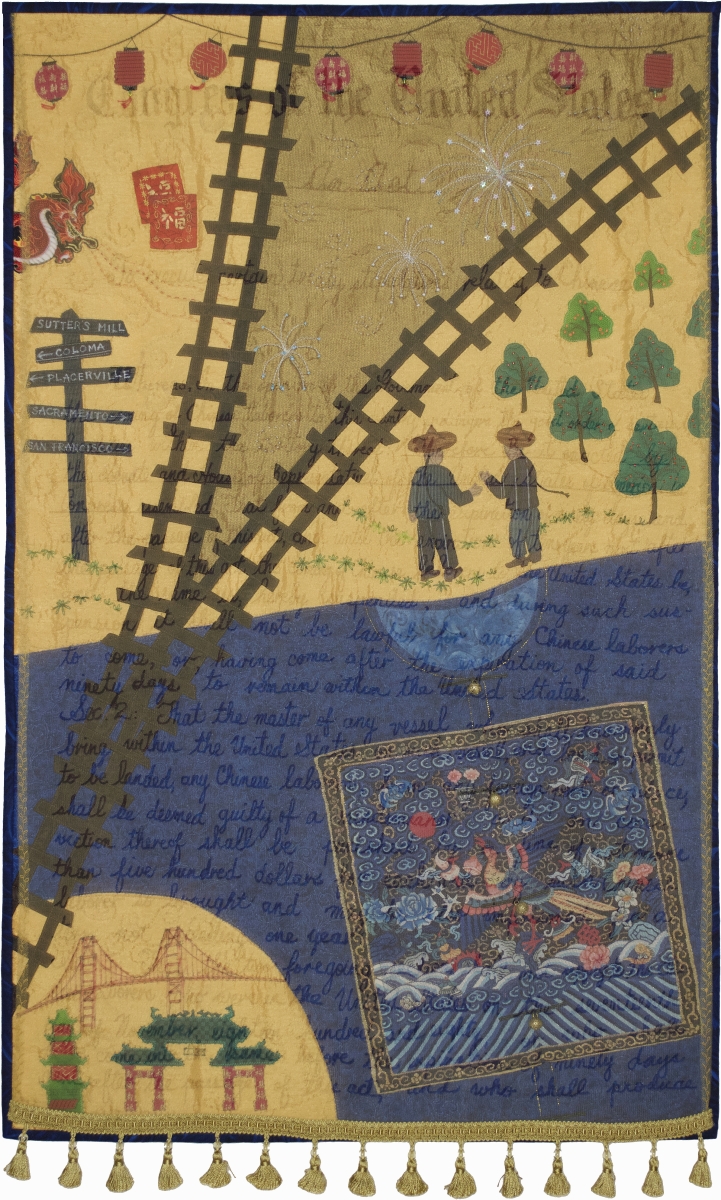

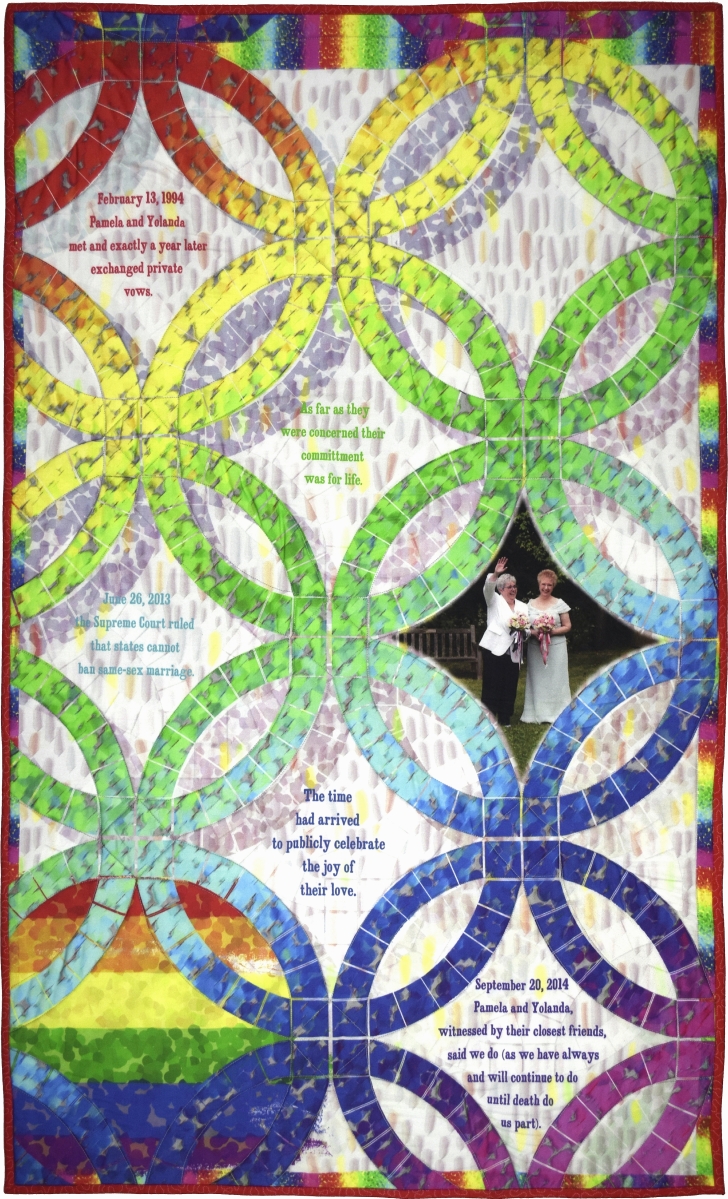

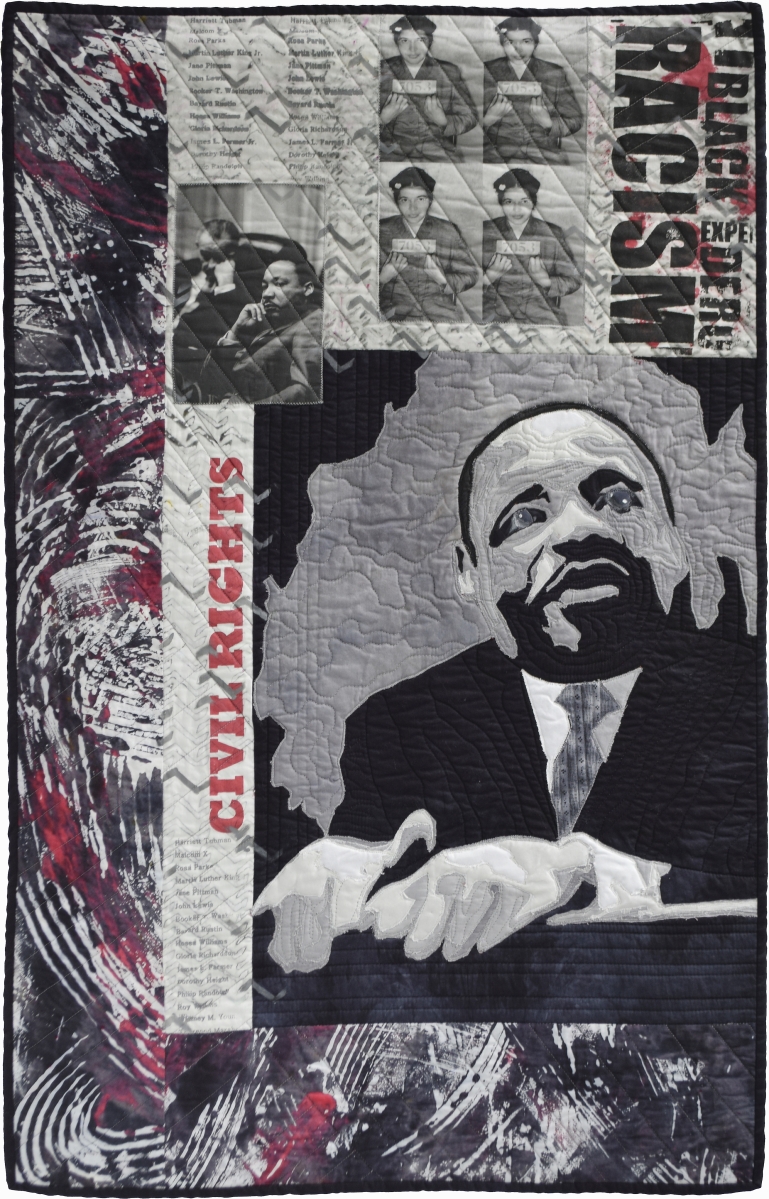

“With ‘OURstory,’ I wanted to celebrate the hard-fought rights we’ve gained over the years by honoring heroes such as the Dalai Lama, Jimmy Carter, Harriet Tubman and Martin Luther King and events like the Women’s March of 2017 and Bloody Sunday in 1965,” Jones says of the exhibition, joyful and inclusive in its stance. Per the organizer’s specifications, all but two quilts on view date to 2017 and measure 25 by 40 inches, closer in size to an oil painting than to a crib quilt. Jones’ role as a curator is often a nurturing one. In one instance, she encouraged her friend Yolanda Fundora to make “A Long Engagement,” celebrating Fundora’s 2014 marriage to her wife, Pamela.

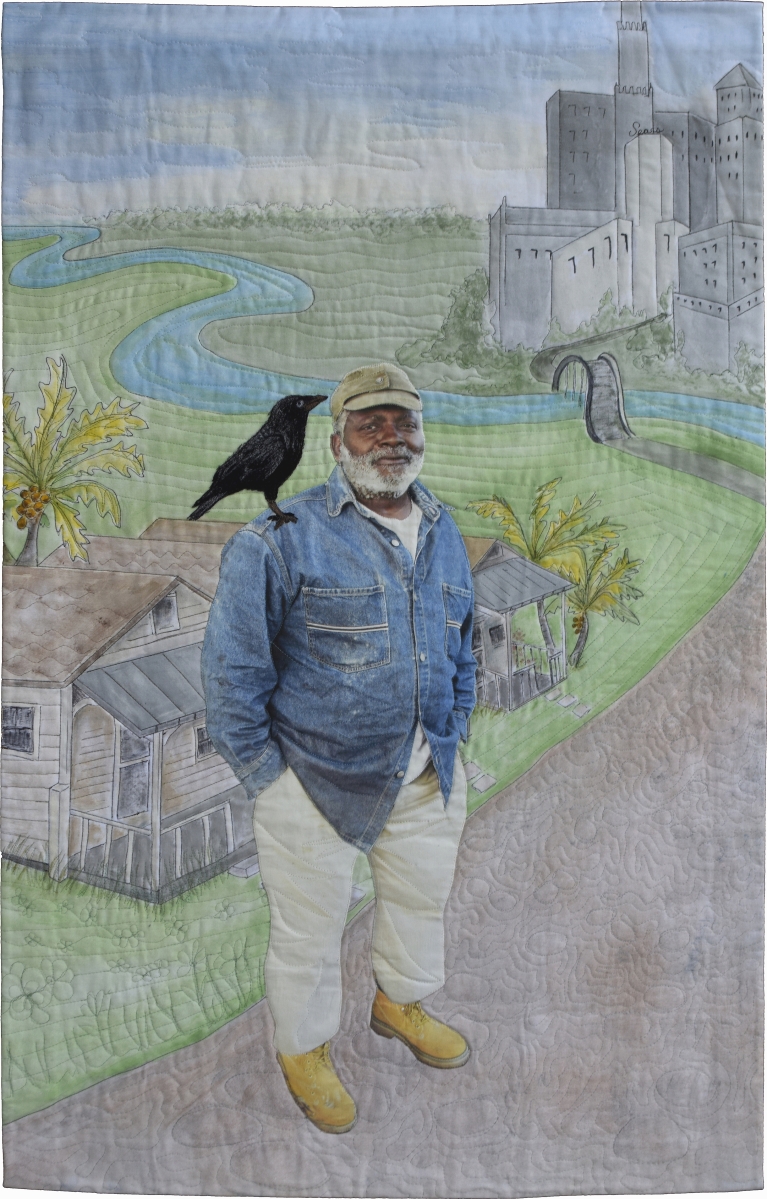

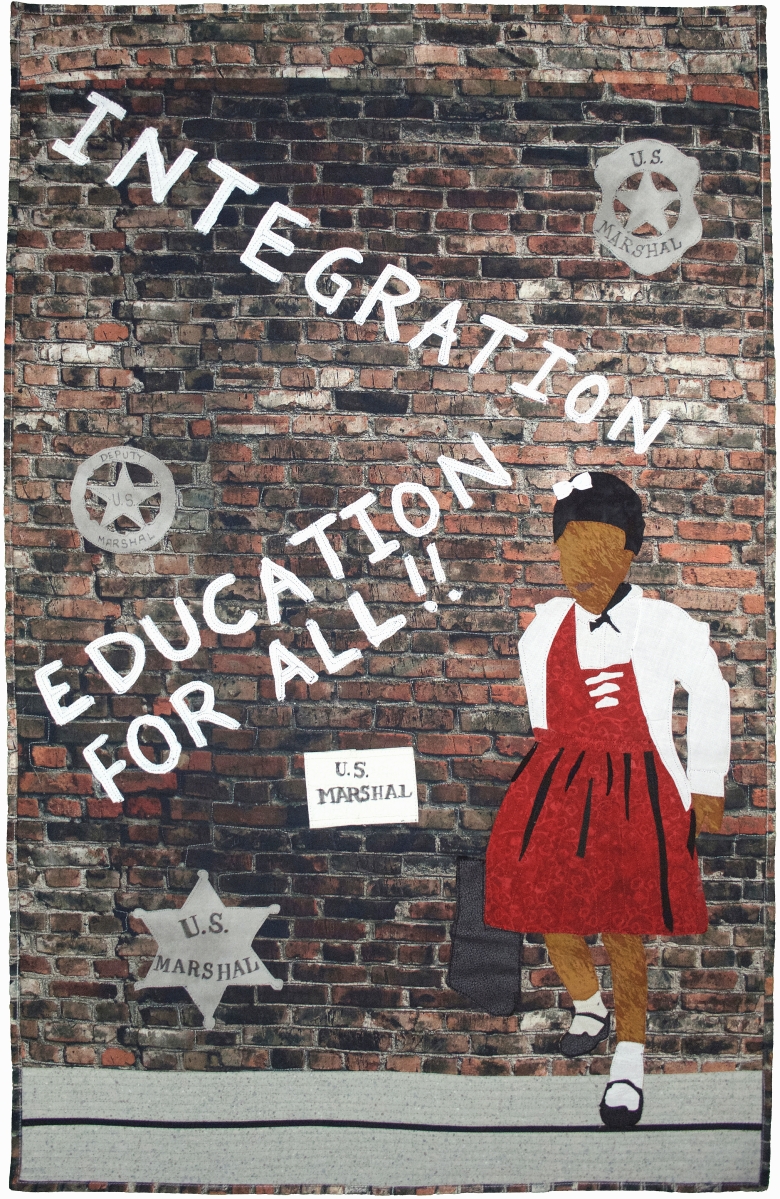

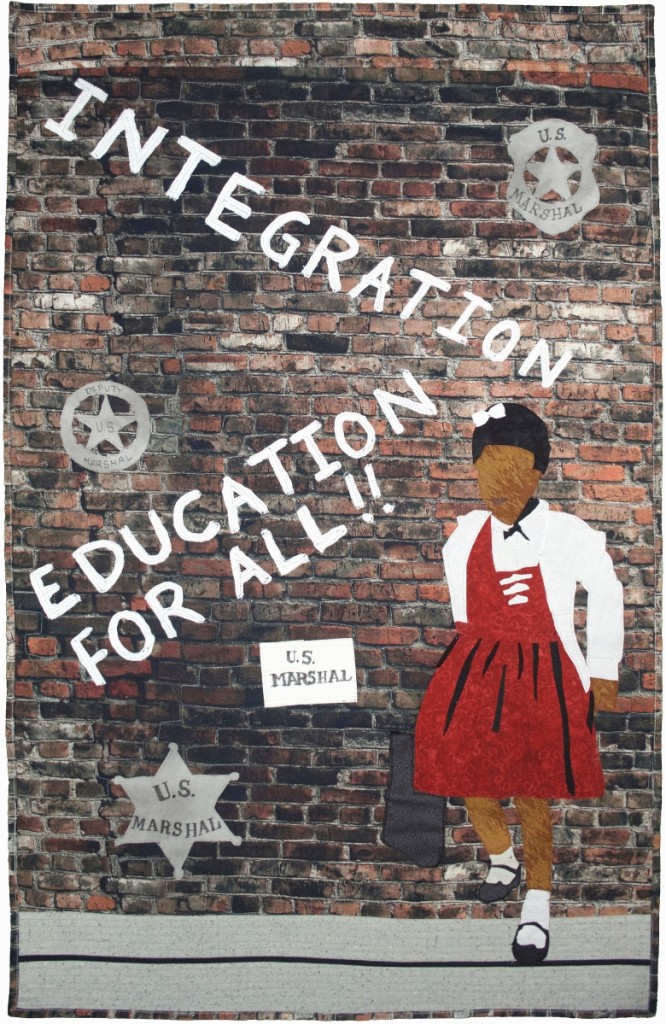

Dedicated to Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, a quilt titled “First Lady of the World” sets the tone for the unfolding display of 65 quilts by 47 artists from six countries. Walking through the gallery on a recent day, Bennett pauses to consider “Ruby Bridges: Standing Alone” by Leo Ransom, one of two male artists represented in the presentation. “The first thing you notice is that Ruby is pressed against a brick wall, an apt metaphor,” the CEO says of the work advocating equality of educational opportunity. Bridges, a civil rights activist painted by Norman Rockwell, was the first African American child to integrate the William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans in 1960.

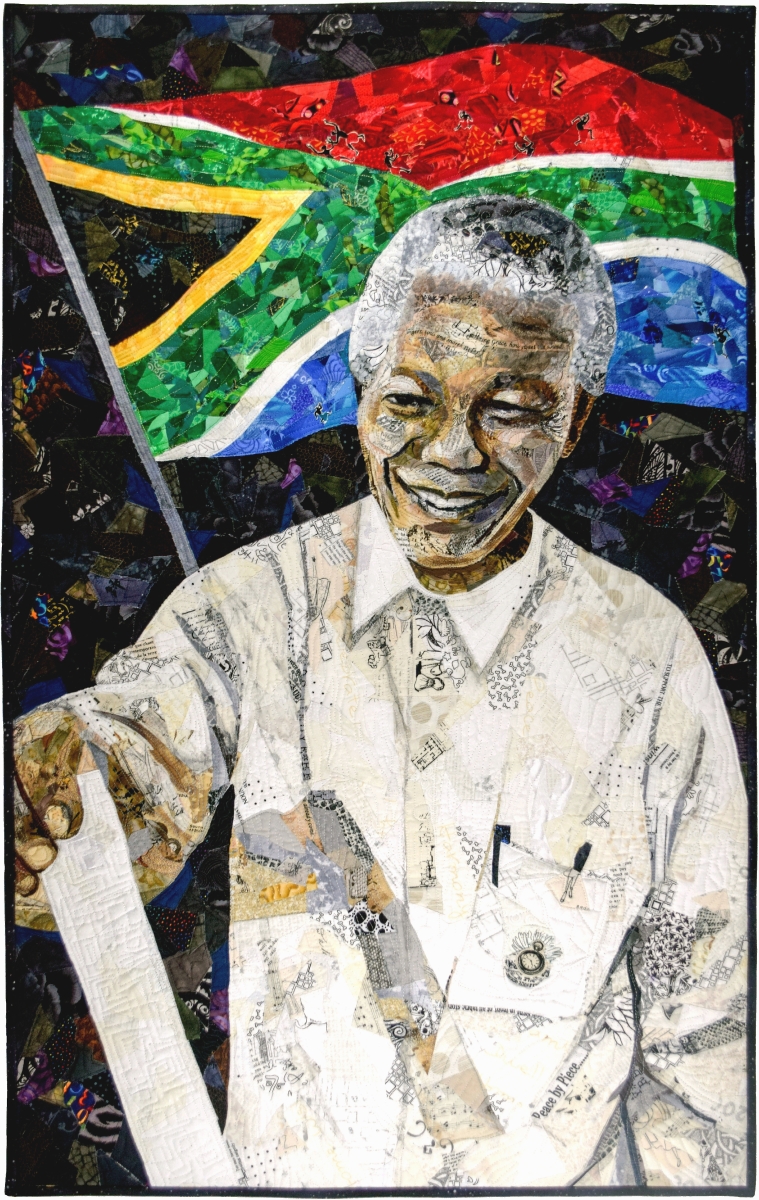

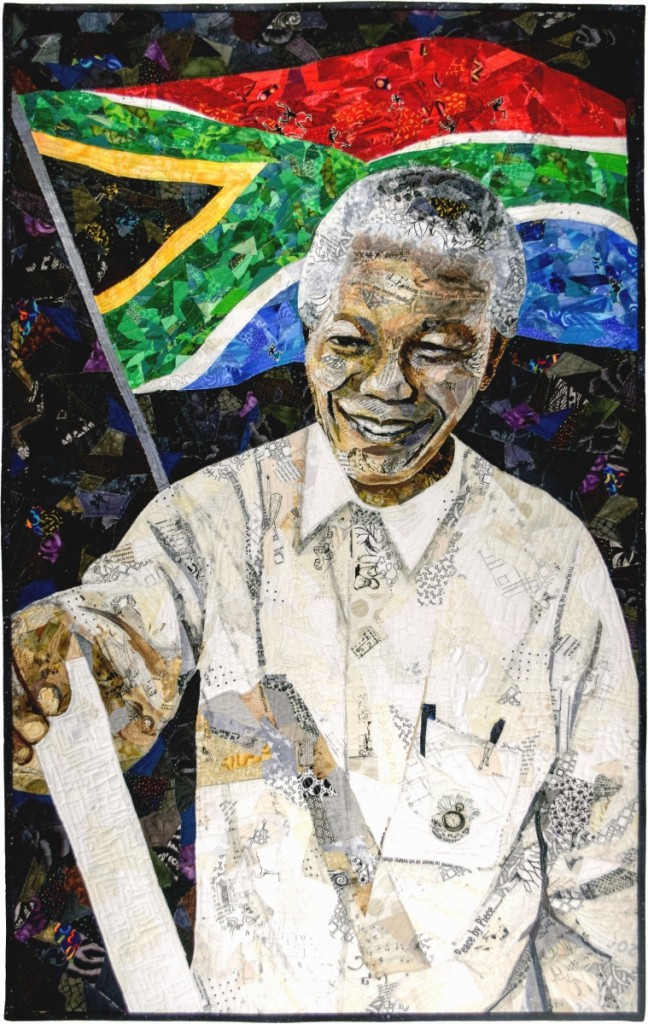

Bennett moves on to “April 27, 1994: Mandela Votes” by Margaret Williams, a quilt dramatic in its foreshortened perspective, intricate detail and freestyle stitching. He says admiringly, “You feel Mandela’s smile. All these little pieces come together to make his expression.”

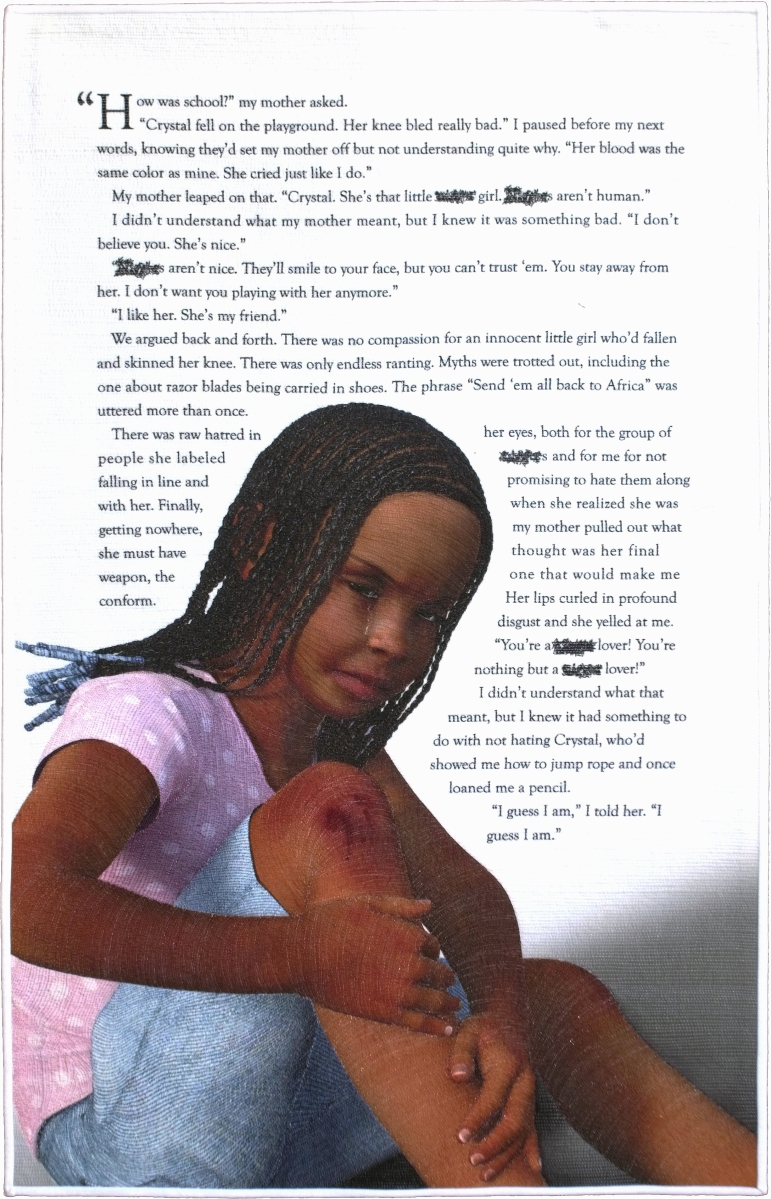

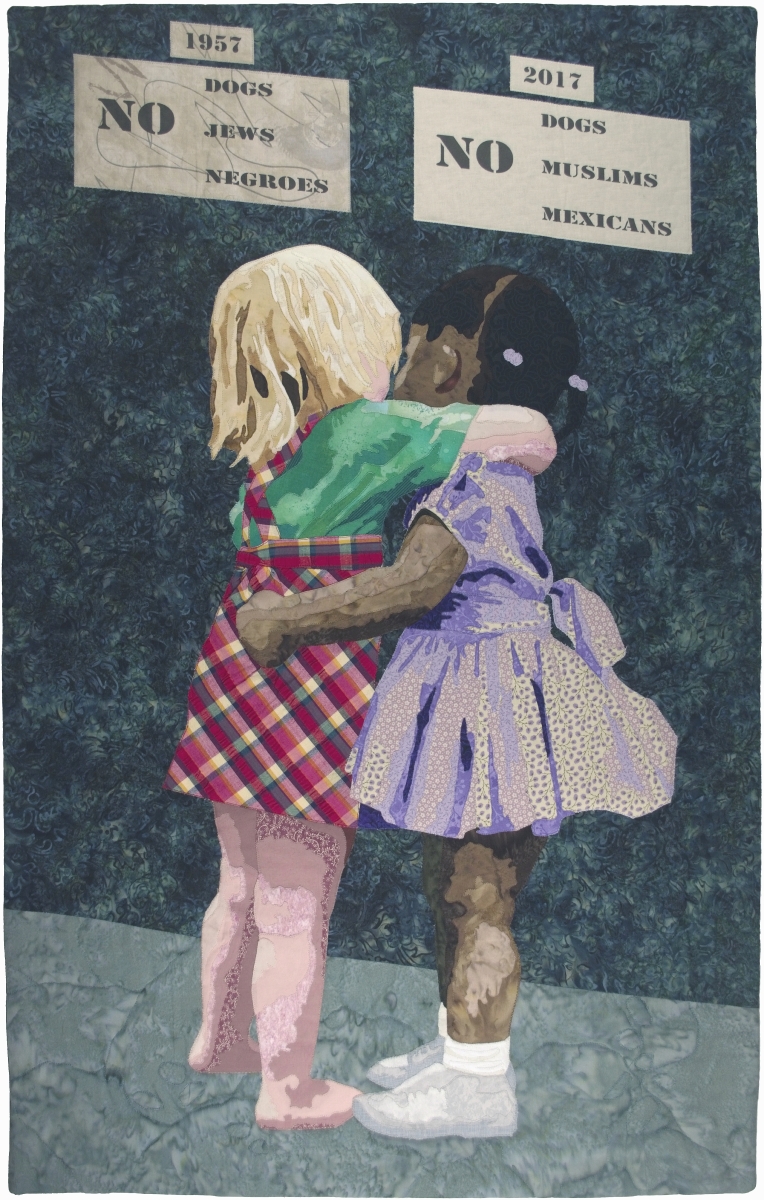

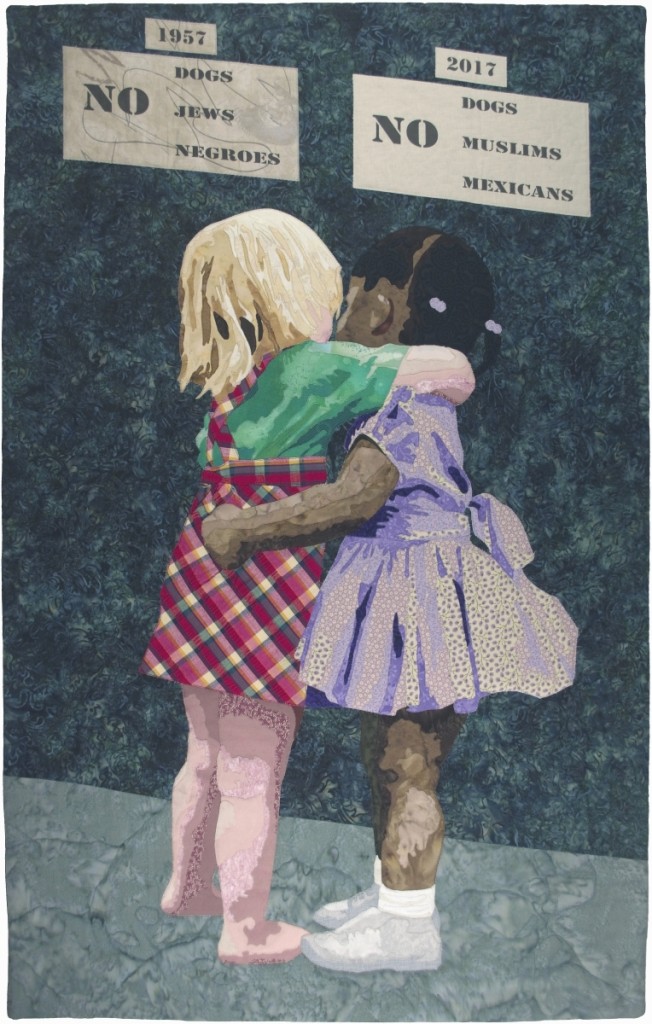

Jones calls a viewer’s attention to two quilts on the theme of race relations, “Seeds of Hatred,” Tanya A. Brown’s searing portrayal of bigotry, and Mary Jane Sneyd’s redemptive “Colorblind.” “I find them an interesting comparison because both reference influences the artists’ mothers had on the women the artists grew up to be,” says the curator, observing of “Seeds of Hatred,” “I’ve seen grown women brought to tears by it.”

Composed in Braille, “Blind Injustice,” an abstract composition by Anne Garretson, is a witty salute to the Americans with Disabilities Act, passed in 1990, amended in 2008 and now perceived as threatened.

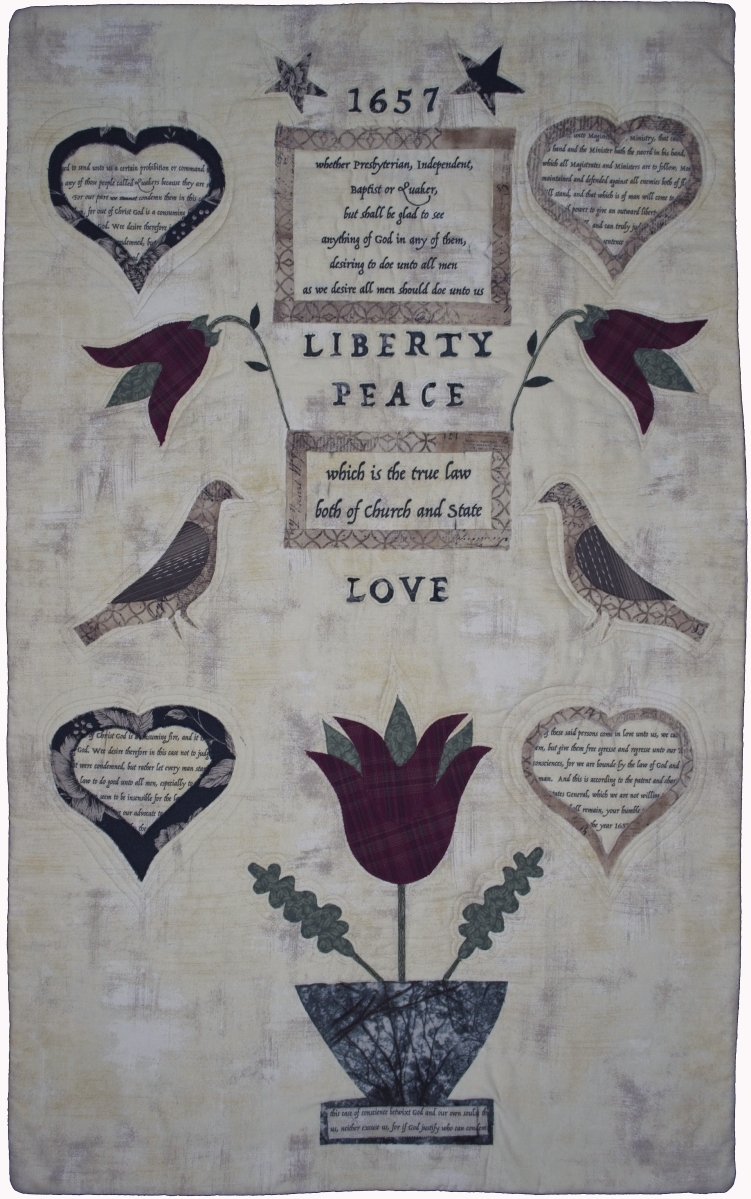

“The Flushing Remonstrance” by Michelle Flamer, a Philadelphia attorney, incorporates motifs borrowed from Pennsylvania German fraktur to recall Peter Stuyvesant’s repressive measures against New York Quakers in 1657.

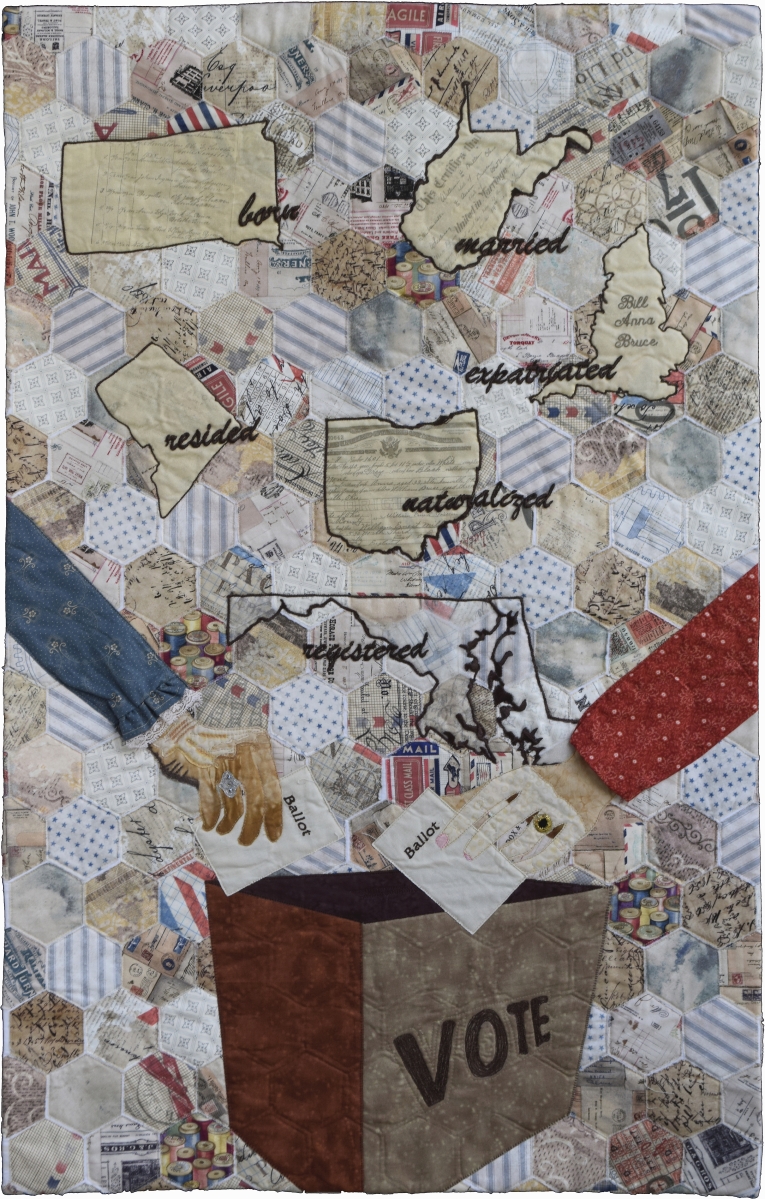

“OURstory” features four of Jones’ own quilts. One, “Suffrage – Long Denied,” an homage to the curator’s own grandmother, who voted for the first and only time at age 84, combines in striking fashion traditional piecing with imaginative, almost trompe l’oeil embellishment.

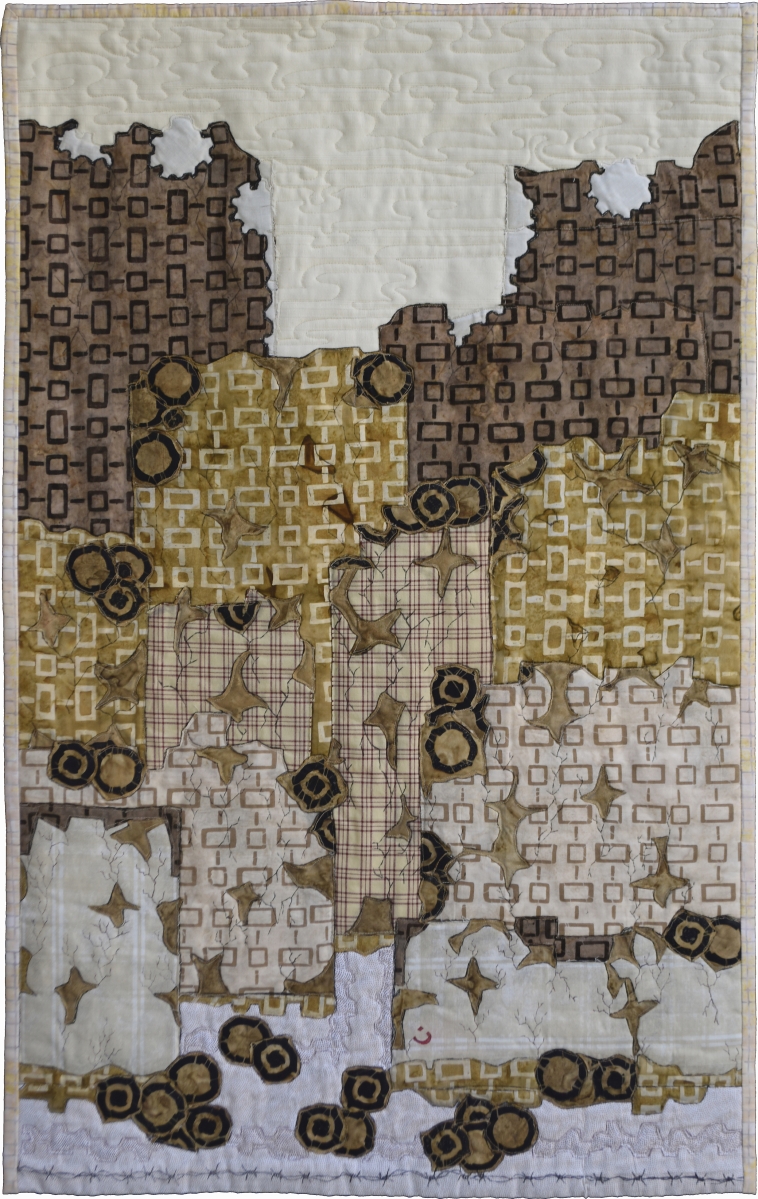

From her own collection, Jones lent a boldly graphic quilt made in 2014 by Mary M. Pettway, a third-generation master quilter and member of the Gee’s Bend Collective in Alabama. The quilt has special meaning for Jones, who acquired it directly from the artist and whose own mother was from Alabama. Gee’s Bend residents were discouraged from voting for 44 years by the closure of a ferry service that helped them get to the polls.

“OURstory: Human Rights Stories in Fabric” opened in 2018 at America’s biggest quilt show, the International Quilt Festival in Houston. Following its close in Paducah, it makes nationwide stops through 2021.

A companion book by Jones, OURstory Quilts: Human Rights Stories in Fabric, with a foreword by Tom Berlin, is published by Schiffer and is for sale at www.schifferbooks.com and other vendors. It illustrates every quilt in the exhibition with a full discussion of the textile printed alongside.

Response to book and exhibition has been overwhelmingly positive, readers and visitors noting the thoughtfulness and beauty of the collection, along with the power of its inspirational message. The project, writes award-winning artist, author and teacher Lea McComas, “dares us to be our better selves at a moment when we, as citizens of the U.S., and citizens of the world, face new challenges regarding human rights and human decency.”

Having devoted a decade to creating books and exhibitions, Jones is shifting gears. “Everyone knows me as a curator and author. I decided after ‘OURstory’ to work on my own art, which is really important to me. It was getting a little crazy sharing my living space with 348 quilts and shipping three exhibits in a timely fashion,” she says.

The National Quilt Museum reopened on June 8 after having been closed for two and a half months. Attendance is growing daily. “It’s going to take time to rebuild visitation,” Bennett says, noting, “I hope ‘OURstory’ causes people to deepen their knowledge of human rights issues and come out having some meaningful discussions, which will help improve sensitivity to equality issues.”

The National Quilt Museum is at 215 Jefferson Street. For more information, 270-442-8856 or www.quiltmuseum.org.

.jpg)