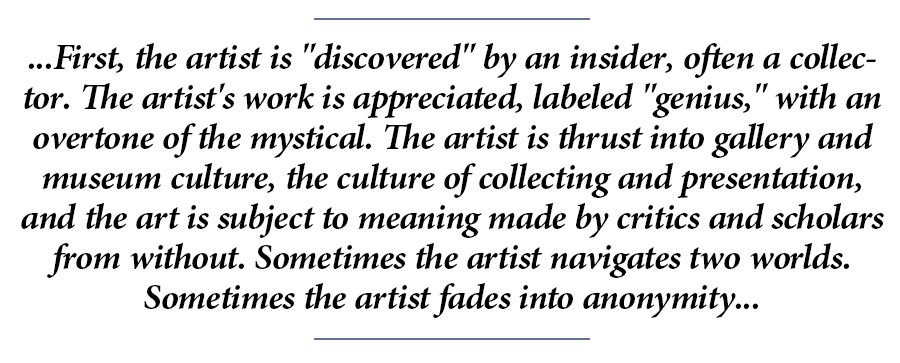

“Interior” by Horace Pippin, 1944. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, gift of Mr and Mrs Meyer P. Potamkin, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the National Gallery of Art.

By James D. Balestrieri

WASHINGTON, DC – “Outliers and American Vanguard Art,” at the National Gallery of Art through May 13, posits an eternal question, one that applies to all human relations, not just the arts: in or out? To elaborate: who decides who is in and who is out? Who belongs to some school of art or “ism” and who should be excluded? The exhibition pushes even at the boundaries of this question, wondering whether artists get to choose whether to be in or out, wondering whether it matters either way or whether it ought to matter at all.

What artists decide for themselves and what is, and has been, decided for them is crucial to understanding the history of Outlier art, the latest in a long line of terms for artists who are largely self-taught, who create out of a desire, often obsessively, to make art in some form, typically with found materials or within the craft traditions of their own cultures.

Folk, Visionary, Primitive, Art Brut, Outsider and now Outlier – these are the terms of the debate, beginning with a scholarly appraisal of American folk art after World War I. What opposes these varied and various terms is what the exhibition – rather politely, in my view – calls American vanguard art. What we are talking about here is American Modernism in all its permutations and combinations as it was and continues to be defined by collectors, institutions and scholars.

This is a difficult subject, but curator Lynne Cooke’s accompanying catalog, Outliers and American Vanguard Art, does a nice job of tackling it while paying proper attention to the art and artists. Other reviews and essays about “Outliers and American Vanguard Art” may concentrate on the incredible artistry on view, but I think it is crucial to say something about the history of the dichotomy between “high” and “popular” art, between “fine” and “folk” art and about the blurring of the lines between them that begins around 1900.

The Arts and Crafts Movement, as an example, builds its aesthetic on unornamented, utilitarian, “folk” forms. Think Shaker. Art Nouveau’s colors and swirls dominate in popular publications and sheet music. The explosion of illustration opens new paths in art, especially to women. Psychology, that newest of sciences, suggests that the impulse to make art is a product of the unconscious imagination, both individually and collectively, that this impulse is ancient and ubiquitous, residing in dreams, in fantasies, in the imagination. Artists from Picasso on down look to African tribal masks and Japanese woodblock prints tap into the subterranean rivers of non-Western, untainted, “primitive” forms.

It is not a big leap from this to the Surrealists’ interest in the art of the insane or to Paul Klee’s interest in the art of children. From there, a look back at folk arts in the 1920s and a search for contemporary unschooled artists after that, and Art Brut, Jean Dubuffet’s all-embracing Outsider art project after World War II, follows quite naturally. But the friction arose when mainstream, schooled, vanguard artists appropriated Outsider forms while critics and scholars denied Outsider artists a place at the table or relegated them to the status of interesting anomalies.

It is not a big leap from this to the Surrealists’ interest in the art of the insane or to Paul Klee’s interest in the art of children. From there, a look back at folk arts in the 1920s and a search for contemporary unschooled artists after that, and Art Brut, Jean Dubuffet’s all-embracing Outsider art project after World War II, follows quite naturally. But the friction arose when mainstream, schooled, vanguard artists appropriated Outsider forms while critics and scholars denied Outsider artists a place at the table or relegated them to the status of interesting anomalies.

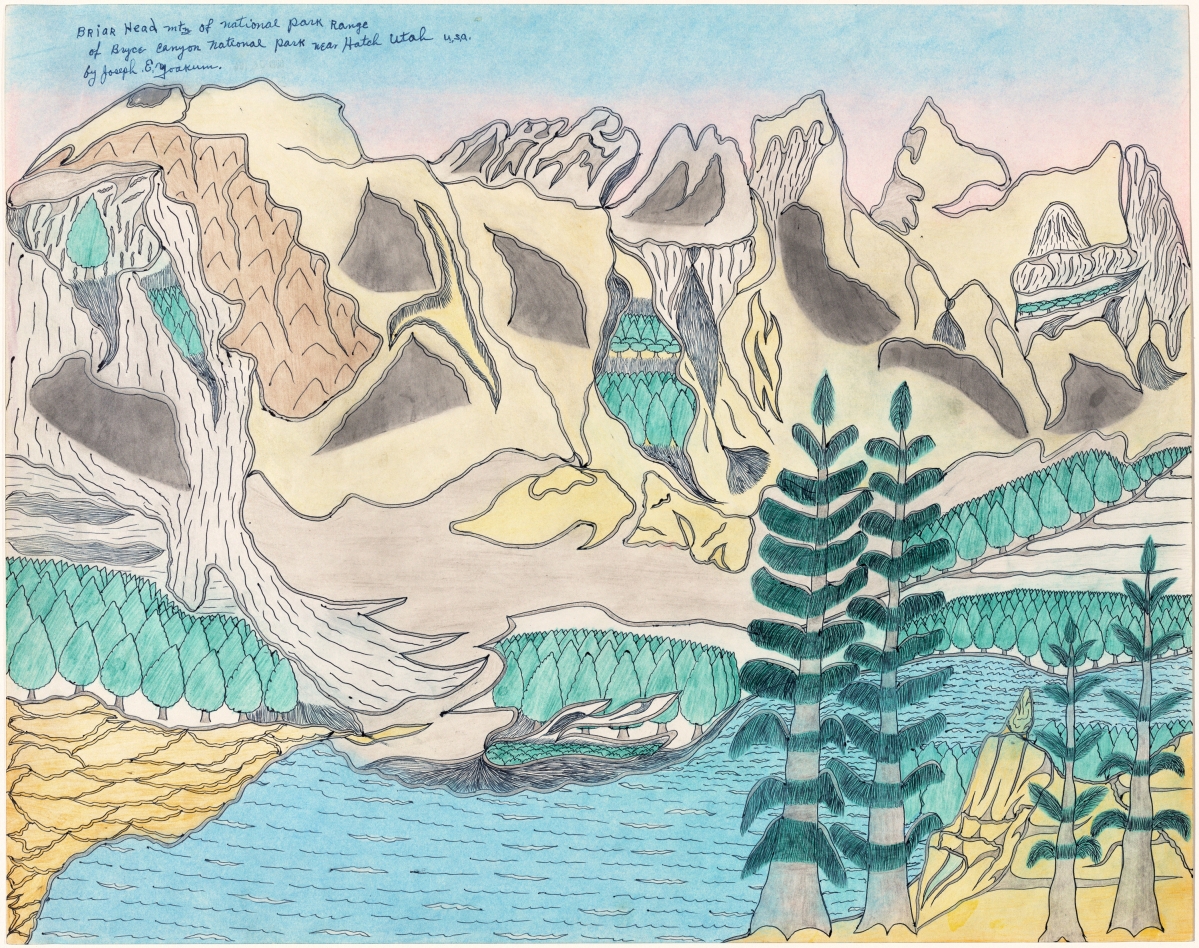

Jennifer Jane Marshall’s poignant and somewhat tragic essay, “Find-and-Seek: Discovery Narratives, Americanization and Other Tales of Genius in Modern American Folk Art,” traces a trajectory common to any number of inspired, unschooled Outlier artists. First, the artist is “discovered” by an insider, often a collector. The artist’s work is appreciated, labeled “genius,” with an overtone of the mystical. The artist is thrust into gallery and museum culture, the culture of collecting and presentation, and the art is subject to meaning made by critics and scholars from without. Sometimes the artist navigates two worlds. Sometimes the artist fades into anonymity. Sometimes the artist rejects the gallery and museum. The point is that the Outlier artist’s impulse to make art, the inspiration, as well as the art itself, are already there prior to the artist’s “discovery” by an “expert.”

The exhibition breaks the ascent of Outlier art into three periods, all of which relate, as critic Harold Rosenberg wrote, to Modernism’s assault on traditional notions of “taste” and representational art.

From 1924 to 1943, the emphasis is on historical American folk arts and the “discovery” of self-taught artists such as painter Horace Pippin, sculptor William Edmondson and their champions at the Museum of Modern Art, in the WPA artist programs and among mainstream artists like Elie Nadelman and gallerists like Peggy Guggenheim. From 1968 to 1992, partly as a response to the civil rights movement, a renewed interest in ethnic identity, gender and sexuality informs the practice of many artists. James “Son Ford” Thomas and Betye Saar are two among many who worked, often by choice, outside the mainstream. From 1998 to 2013, and through to the present, Outlier artists resist aesthetic nomenclatures and are equally wary of attempts to bridge Outlier and mainstream. Rosie Lee Tompkins and Matt Mullican, as examples, work under alter egos, constructing their own identities and worlds.

The backgrounds of Outlier artists are varied. They can sometimes be urban but are more typically rural. They can be African American, Hispano American or indigenous. They can be mentally challenged or hermetic and reclusive. Many women who historically found themselves excluded from the mainstream are counted, and count themselves, as Outlier artists. Few are wealthy or highly educated.

“Briar Head Mtn of National Park Range of Bryce Canyon National Park near Hatch, Utah U.S.A.” by Joseph Yoakum, circa 1969. Blue-black and black ballpoint pen and colored pencil on paper. National Gallery of Art, Washington, gift of the Collectors Committee and the Donald and Nancy de Laski Fund.

As for the stuff of Outlier art, you see materials that are unusual (cardboard, string, teeth, nylon stockings, discarded wood and metal) or accessible (photographs) and forms that might be utilitarian (dolls and quilts) or utterly novel. Outlier artists use what they have, and what they know.

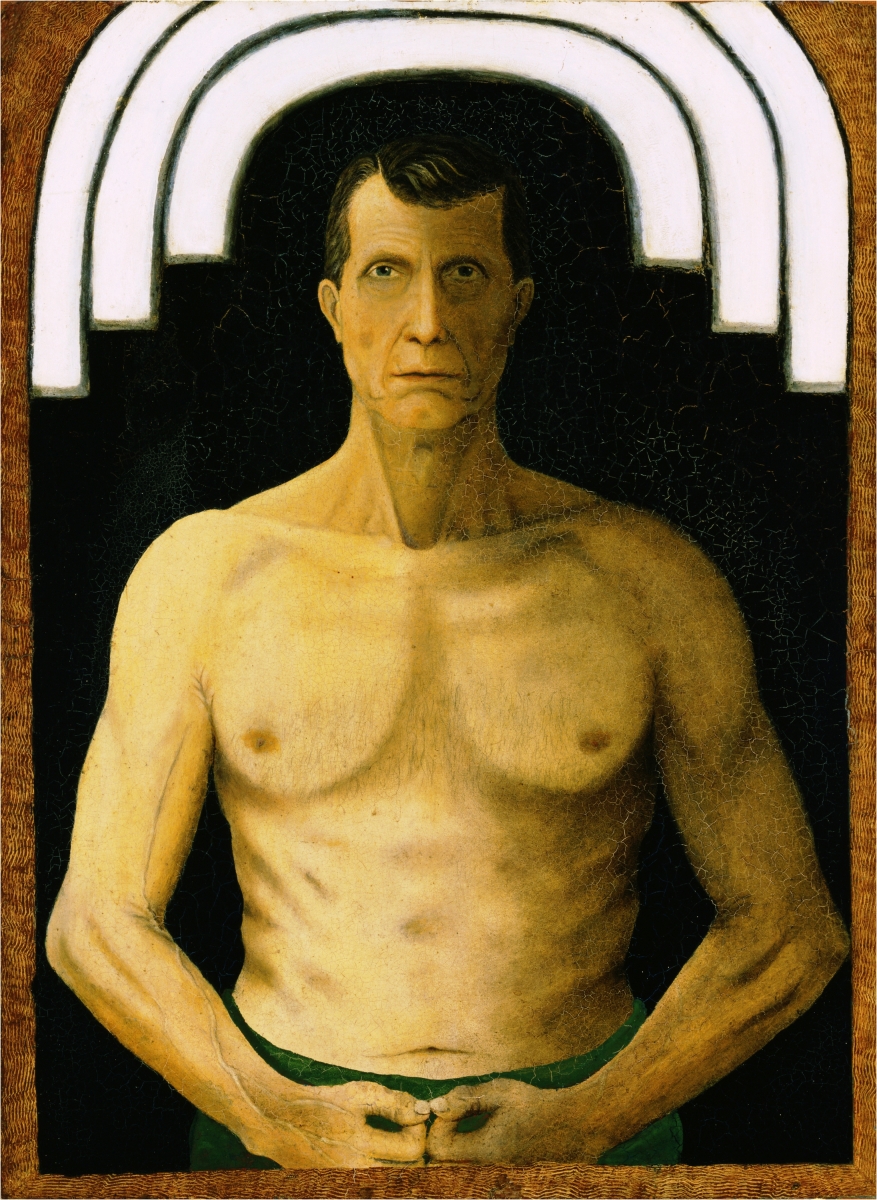

You can see instantly why Modernist painters would be drawn to Horace Pippin’s “Interior.” Pippin, whose wounds in World War I occasioned his interest in art as a kind of therapy, paints quite naturally in ways it would take a Matisse or Hartley years to achieve. Consider Pippin’s play with perspective, his simply drawn yet strangely affective figures, and the fields of color that create his compositions.

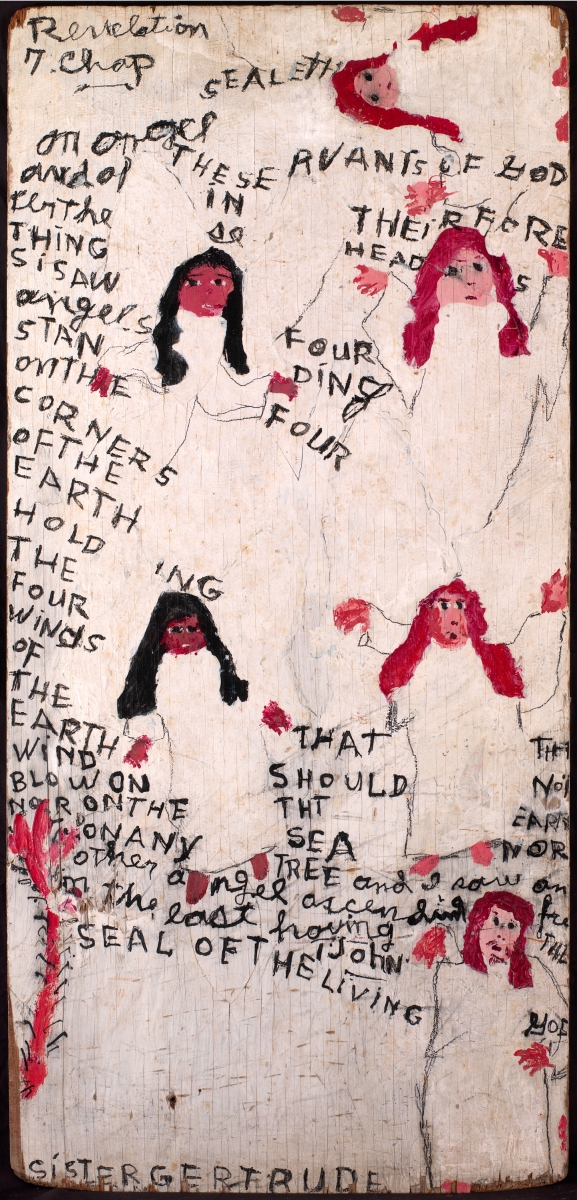

Many Outlier artists draw on their spirituality for inspiration. Marvin Johnson’s “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” is one of a number of paintings he did to make well-known gospel hymns into visible manifestations of divinity. William Edmondson believed he was called to sculpt works such as the rough limestone “Angel.” Edmondson felt that he found the works in the stone, that his faith released them into the world. Lonnie Holley’s construction of bones and discarded metal and wire, “The Boneheaded Serpent at the Cross (It Wasn’t Luck),” is as direct as it is obscure, referencing mortality and salvation, fortune and fate, falling and rising, in a delicate balancing act.

Betye Saar’s “Indigo Mercy” seeks to explore and perhaps restore some of the shorn spirituality of ritual objects when they are displayed in museums. In the work, an old chair is transformed into a shrine. That Saar is about to be honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award by the International Sculpture Center attests to Saar’s appreciation in the larger art world while in no way diminishing her Outlier status.

Photography was only one of many media that Milwaukee baker Eugene von Bruenchenhein worked in, but the photographs he took were almost exclusively of his wife, Marie, whom he envisioned as a pinup in the Betty Grable mode.

“Men Drinking, Boys Tormenting, Dogs Barking” by Bill Traylor, circa 1939–42. Opaque watercolor on card with dark gray prepared surface. Collection of Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz, promised gift to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

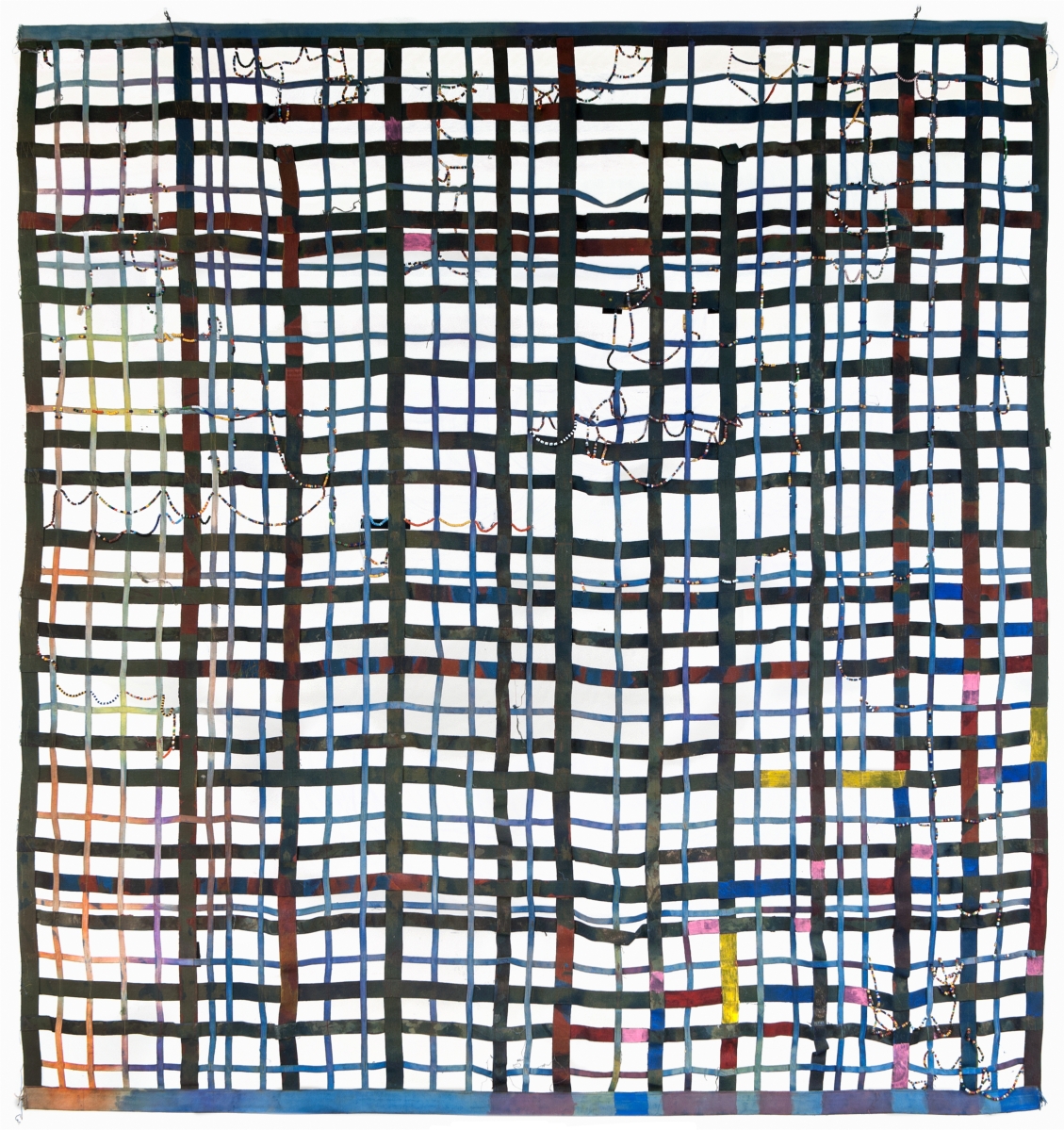

The carefully wrapped objects that characterized Judith Scott’s work are painstakingly crafted. Strings and knots call attention to shapes in the way that, say, Christo’s giant wrappings cause us to look at large natural and human-made forms we may take for granted. Scott, who had Down’s syndrome and was deaf, created works that resonate like the musical instruments of some unknown and unknowable people, lost to time. The strings and beads vibrate over the shapes, communicating in a music we are deaf to.

When you are told, often enough and for long enough, that you are on the outside you will eventually assume the identity of an Outsider. You’ll wear it as a badge of honor until others want what you have, want to share in the identity you have fashioned for yourself. Out becomes in. This is the oscillation in society, and art. If schooled artists – artists in the sense that we think of artists – see the stars and draw new lines, making new constellations, you might say that Outlier artists see different stars and draw new constellations between them. But the one line that is erased when we are moved by any work of art, a line as inevitable and human as it is ultimately artificial, is the line between in and out.

On view in the National Gallery’s East Building Concourse Galleries, “Outliers and American Vanguard Art” was organized by Lynne Cooke, senior curator, special projects in Modern art. Following its close in Washington, the show featuring 300 works travels to Atlanta’s High Museum of Art from June 24 to September 30, and to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art from November 18 to March 18, 2019.

The National Gallery of Art is between 3rd and 9th Streets along Constitution Avenue NW. For information, 202-737-4215 or www.nga.gov.

Playwright, author and critic James D. Balestrieri is director of J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York City.