“The Epic of American Civilization,” detail of wall mural by José Clemente Orozco, 1932–34. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College.

By James D. Balestrieri

PHILADELPHIA, PENN. — Diego Rivera. Frida Kahlo. When we think of Twentieth Century Mexican art, these are the names that spring to mind. And why not? Their bold art, leaping out of the Mexican Revolution and its aftermath, remains radical, epic, visionary, simultaneously political and personal. As people, Rivera and Kahlo fascinate us. On top of their art, their tempestuous love through tumultuous times, touching the worlds of Rockefeller and Trotsky alike, is the stuff of novels, films, dreams. For good measure in our quick mental survey of art history, we temper the magnificent Rivera murals with those of David Siqueiros and Jose Orozco, spare a thought for Rufino Tamayo and move on.

“Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910–1950,” on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through January 8 before moving on to the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City from February 3 to April 30, explodes our far-too-cozy notions about Mexican art. It locates Rivera and Kahlo in the heady brawl of artists and ideas that rose out of the successful revolution against the dictatorial presidency of Porfirio Diaz that began in 1910 and came to a conclusion with the election of Álvaro Obregón in 1920.

Like Lenin after the Russian Revolution of 1917, Obregón saw the need to marshal the arts, not only to depict the revolution, but also to serve its aims and ideology. José Vasconcelos, who would head the new Ministry of Public Education, “assembled a network of painters who would produce monumental murals in public buildings. These murals had a public and educative purpose, commemorating Mexico’s indigenous history and traditions, narrating the struggles of the people since the Spanish conquest in the Sixteenth Century, and depicting the history and ideals of the insurgency.” Art, in short, should unite Mexico, adapting from Marx the notion that a chiliastic period has begun, a period characterized by good government and prosperity for all, achieved and maintained by the workers of the fields and factories.

“Liberation of the Peon” by Diego Rivera, 1931. Fresco, 73 by 94¾ inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

How different the situation in Europe was. The First World War had decimated the Continent. The image of the charnel house trenches, filled with the masses, stood as a nauseating reproach to the failures of bourgeois and aristocratic capitalism. Art in Europe — and it should be remembered that many artists, composers and writers lost their lives on those battlefields — turned inward, away from the world, seeking itself in notions of expression, imagination, dreams and the “primitive” forms of Africa and Asia. Russia had its own successful revolution, becoming the Soviet Union, where the state quickly took control of the media and arts. But Mexico was a nascent democracy. Many artists (but not all) turned away from Europe as a model. Most felt some affinity with the Soviet Union. But there were vehement, sometimes violent disagreements about how closely Mexico could, or should, hew to the Communist Party line. Competing ideas about how art could best serve postrevolutionary Mexico burgeoned and clamored for attention.

One other crucial thing separated Mexico from Europe. While all the nations of Europe (and Russia) had strong folk traditions (as did Mexico), only Mexico had an ancient, indigenous civilization from which to draw artistic — and patriotic — inspiration. The pyramids, temples, carvings, paintings and artifacts of the Aztec, Mayan, Olmec and Toltec peoples offered Mexican artists a local mythology and iconography that they could appropriate, share and amplify. Indian cultures; campesino folk traditions; archaeological treasures to rival Egypt and Greece; a strong Hispanic Catholic culture; an urban, cosmopolitan intelligentsia; a rapidly expanding class of industrial workers — how to forge a nation from all this was, and perhaps is, the Mexican question.

One way to unify a nation through art is to create a common visual language. Artist Adolfo Best Maugard attempted to answer the question by writing a book, Drawing Method: Tradition, Resurgence, and Evolution of Mexican Art, that was adopted in Mexico City schools. Maugard had studied with the anthropologist Franz Boas, cataloging pottery, and had determined “that ornamental motifs and their repetition were based on seven elements — spiral, circle, half circle, ‘s,’ wavy line, broken line and straight line — that could be infinitely combined.” Students, enjoying complete creative freedom from traditional drawing methods, would build on these elements and create a uniquely Mexican art. Though Maugard’s method prevailed for only a few years, many artists adapted his teachings. María Izquierdo’s 1943 painting, “Altar de Dolores,” for example, is constructed from the elements Maugard advocated.

Orozco’s “Epic of American Civilization,” which, tellingly, was commissioned by Dartmouth College and featured works by Rivera and Siqueiros such as “Liberation of the Peon” and “Peasants,” celebrates the heroism of rural Mexicans, whether they are sacrificing themselves for the sake of the country or stewarding the land with simple nobility. The stance of the muralists is comprehensive, capturing the sweep of history through strong, solid forms. Narrative dominates. But their influences are as varied as the religious frescoes and stained glass of Europe and the Cubism of Picasso. Rivera’s fine, if derivative, “Portrait of Guzman,” painted in 1915 while he was in Paris, reveals this.

Orozco’s “Epic of American Civilization,” which, tellingly, was commissioned by Dartmouth College and featured works by Rivera and Siqueiros such as “Liberation of the Peon” and “Peasants,” celebrates the heroism of rural Mexicans, whether they are sacrificing themselves for the sake of the country or stewarding the land with simple nobility. The stance of the muralists is comprehensive, capturing the sweep of history through strong, solid forms. Narrative dominates. But their influences are as varied as the religious frescoes and stained glass of Europe and the Cubism of Picasso. Rivera’s fine, if derivative, “Portrait of Guzman,” painted in 1915 while he was in Paris, reveals this.

Working for the government, the muralists quickly became symbols of the new establishment. Just as quickly, the Mexican avant-garde produced a provocative antiestablishment: artists who worked in what were thought to be lesser media, photography and printmaking; artists who felt art must stay outside the political realm; artists who advocated a more international outlook that led them toward Surrealism; women artists and gay artists who were marginalized by the overtly masculine posture of the muralists; artists who felt that the apotheosis of the peasant and worker left the Indian out of the revolution; artists whose extreme nationalism and fear of socialism attracted them to fascism; artists who combined a number of these outlooks, or who switched freely from one to another.

The Estridentistas, for example, aligned themselves most closely, perhaps, with Italian Futurism and its repudiation of the past and vaunting of the machine, of speed and, at times, its dalliance with violence as a means of cleansing culture. Like the muralists, they identified themselves as a movement dedicated to virility and strength.

The Contemporáneos shared an urban sensibility with the Estridentistas, but advanced “a universal cosmopolitanism,” and believed that Mexican culture should remain open to international influences and to the voice of the urban intellectual. Rather than massive murals, they focused on easel painting and small-scale works and published a succession of journals, magazines and illustrated novels. They and their work were seen and ridiculed as products of bourgeois elitism, but it was among the Contemporáneos that women could find a place and voice. It was their insistence on fostering connections to the larger world, including writers as diverse as Andre Gide and Langston Hughes, that simultaneously helped to broadcast the revolution in Mexican arts abroad and to bring Surrealism to Mexico.

“Self-Portrait on the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States” by Frida Kahlo, 1932. Oil on metal, 12½ by 13¾ inches. Collection of Maria and Manuel Reyero.

Against the overtly political backdrop of the various aesthetic schools and movements in Mexico, Frida Kahlo’s emphasis on identity in her multiform self-portraits seems somewhat solipsistic. But with the emphasis on populist masculinity and virility that dominated both the artistic establishment, led by Rivera, as well as important avant-garde movements, such as the Estridentistas, there was little room for women in the public sphere of art. Indeed, María Izquierdo was denied a mural commission, “following bitter public and private attacks that questioned her ability to paint in what was considered a masculine medium.”

Kahlo’s “Self-Portrait on the Borderline,” painted in 1932, underscores the ambivalent attitude of Mexican artists toward the United States in the period between the world wars. Rivera’s commission to paint frescoes for the newly built Rockefeller Center, and the destruction of his work after he was pressed by American leftists to include an image of Lenin (not to mention his intention to portray his patron, John D. Rockefeller Jr, in an unflattering light — martini in hand, harlot on his arm) is well documented. But American patronage was essential to the success of Mexican artists and exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1930 and Rivera’s solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1931 helped many of them to secure commissions and market their works.

In Kahlo’s painting, Mexico is agrarian, ancient, natural and artistic. The United States, on the other hand, is industrial, electrified, steely, modern. Mexican lightning becomes American current. Pyramids mirror factories. Clouds mirror belching smoke. The roots of Mexican flowers touch electric wires north of the border. Still, even in the figure of Kahlo, the long pink dress and lace gloves are undercut by the cigarette she holds. The pedestal she stands on has an electrical outlet into which what seems to be a large microphone is plugged. America might be all those things she does not care for, but it is where the word, her word, gets out.

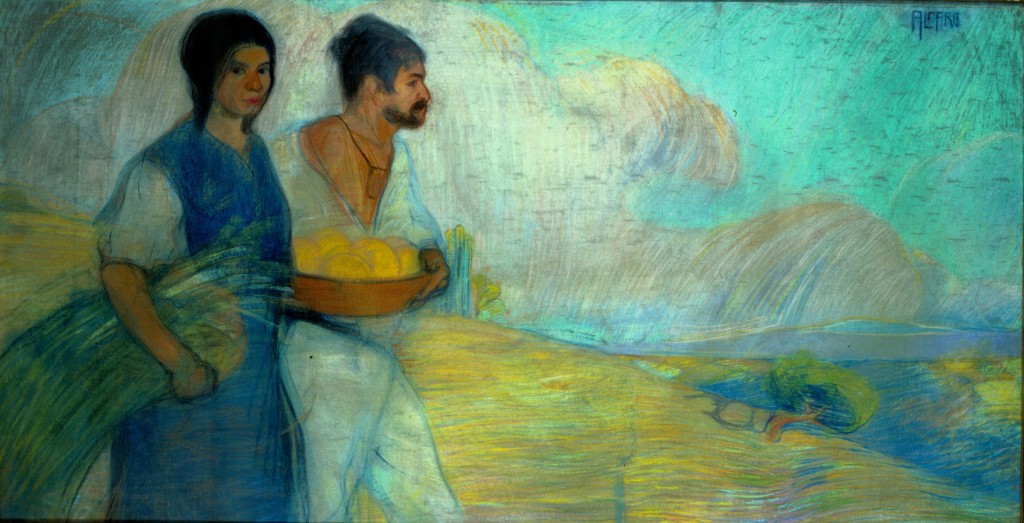

“Peasants” by David Alfaro Siqueiros, circa 1913. Pastel on paper, 40½ inches by 6 feet 3¾ inches. Museo Nacional de Arte.

In “Paint the Revolution,” Mexico becomes, arguably, the real crucible of Modernism, the place where all the strands come together, and fall apart. Rufino Tamayo was a member of the Contemporáneos. The 1952 oil “Homage to the Indian Race,” perhaps the latest work in the show, is a “mural-sized painting, executed in a synthetic industrial paint on Masonite panels, presenting a perennial national folkloric theme — the Tehuana flower seller — in an abstract style that evokes the internationalist trends of the 1950s.”

In other words, while the subject of the work suggests Rivera and the “folklorismo” of the muralists, the style evokes the universalist aspirations of the Contemporáneos. With the choice of industrial paint on a ground of Masonite, Tamayo hearkens back to the Estridentistas’ interest in modern Mexican material culture and to the place of the worker in that culture. At the same time, the vivid colors and textures he achieves dovetail with Willem de Kooning and the Abstract Expressionists. Above all, there are the contortions of the Indian flower seller, alone in a dark, lurid world, beset by… what? Birds? Planes? Laws? Thoughts? Dreams? The work seems to say that civil war and revolution have returned, if, indeed, they ever ended.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art is at 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway. For more information, www.philamuseum.org or 215-763-8100.