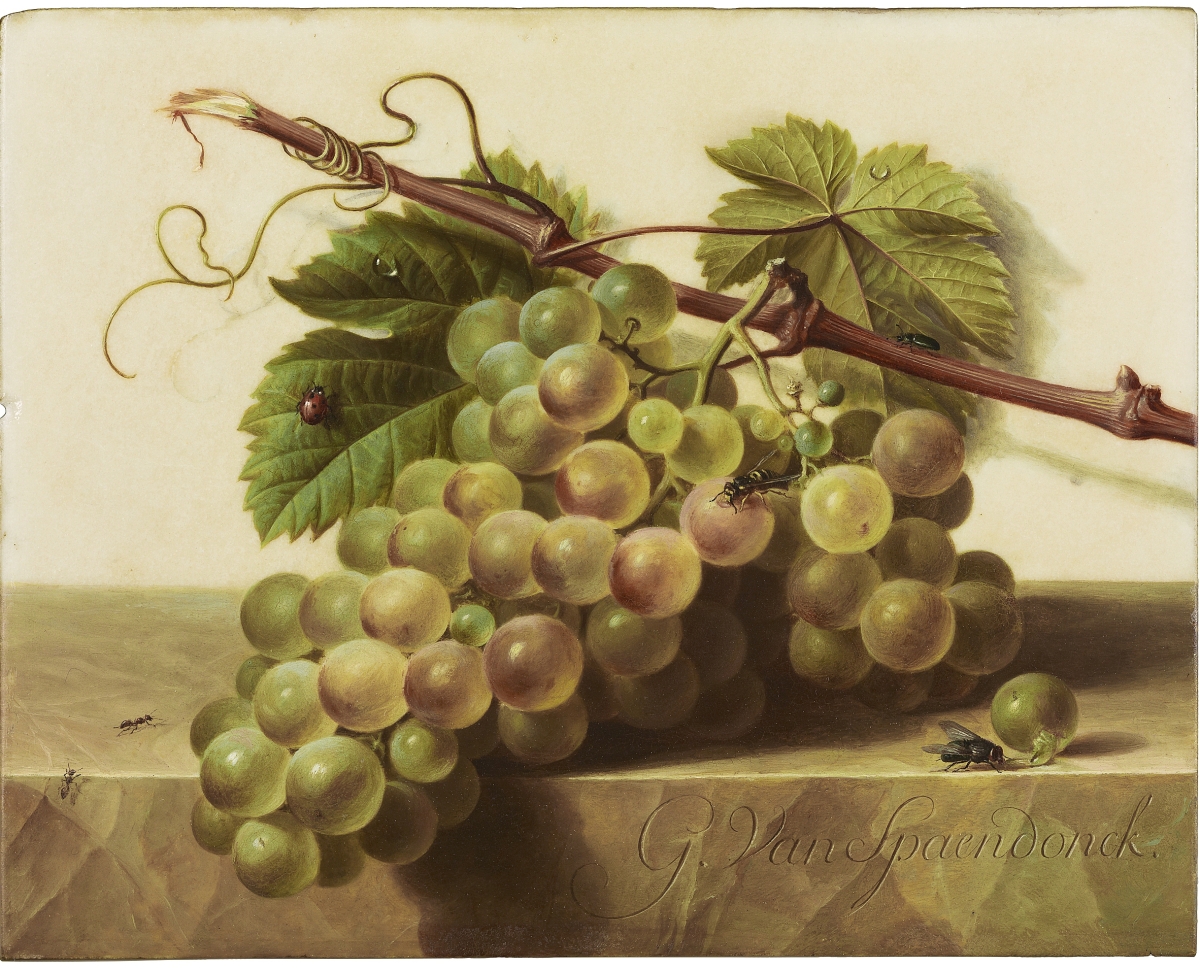

![“Grapes with Insects on a Marble Top” by Gerard van Spaendonck (Dutch [active Paris], 1746-1822), circa 1791-95; oil on marble; 7- 3⁄8 by 9¼ by 1/8 inches; The Frick Collection, New York City, Gift of Asbjorn R. Lunde, 2012; ©The Frick Collection.](https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/14_slam_press_image--paintings_on_stone-1024x827.jpg)

“Grapes with Insects on a Marble Top” by Gerard van Spaendonck (Dutch [active Paris], 1746-1822), circa 1791-95; oil on marble; 7- 3/8 by 9¼ by 1/8 inches; The Frick Collection, New York City, Gift of Asbjorn R. Lunde, 2012; ©The Frick Collection.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

SAINT LOUIS, MO. – The long history of painting on stone dates back to prehistoric times, when hunter-gatherers painted magnificent scenes of animal life on the interior walls of caves from Indonesia to Lascaux, France. No less fascinating is the resurgence of painting on stone during the High Renaissance in Europe, when rising interests in science and exploration, emerging religious and theological debates and the coming of age of painting itself all overlapped. This phenomenon is the subject of “Painting on Stone: Science and the Sacred, 1530-1800,” at the St Louis Art Museum (SLAM) to May 15.

By the Renaissance, most paintings that were not frescoes were produced on either wooden panels or stretched canvases. Those materials were widely available and relatively transportable, allowing paintings to be more easily bought, sold, collected and displayed in massive quantities. Why then, would a group of artists in the 1500s turn so passionately back to heavy, inflexible, immovable stone as a support? The present exhibition is less about explaining precisely why that happened than it is about celebrating and witnessing this art-historical moment; nevertheless, delving into some of the “whys” opens the door to two central themes that curator Judith Mann thoughtfully explores. First, stone’s physical qualities offered visual possibilities that other painting supports did not; and second, stone as a material, an element of nature, could often connect meaningfully to subject matter across a wide cultural landscape of myth and theology.

Painting on stone had its revival in a time and place where cultural life centered around the Catholic Church. The Protestant Reformation had spread across northern Europe throughout the 1500s, but Southern Europe – Italy, Spain, parts of France – had remained staunchly Catholic. Under the guidance of the Papacy, artists doubled down on Catholic theology as part of what has come to be known as the Counter-Reformation. A key concept was that religious imagery played an essential role in the development of a spiritual life, a practice that newly minted Protestants frowned upon. The artists of the Counter-Reformation placed new focus on devotional works that stressed the physical and emotional aspects of their faith within well-established Christian iconography – and many found that stone supports uniquely aided them in that task.

First, there was the issue of permanence. Works made for devotional purposes were often touched and handled, and pigments could wear away over time. Mann explains that the painter Sebastiano del Piombo, originally from Venice but working in Rome, was the first to experiment with a stone surface to create a more durable and hence “eternal” painting. The idea was that a semiporous stone support would allow the pigments to seep in and become a lasting part of the stone itself, as formidable as sculpture. Piombo’s experiments in the 1530s were not completely successful, but they inspired generations of later artists. Soon, as Mann chronicles, artists begin to leave portions of stone uncovered in their compositions in order to harness its visual possibilities.

“Portrait of a Young Man” attributed to Sofonisba Anguissola (Italian, 1532-1625), late Sixteenth Century; oil on slate; 27-1/16 by 19-3/16 by 7/16 inches; Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico.

Slate – flat, dark, and smooth yet soft – was a favored surface for these earlier works. In portraits on slate, like Sofonisba Anguissola’s portrait of a young man, facial features and other details stand out against the black background, making the figure seem to emerge physically from the darkness. Something similarly powerful happens in nighttime scenes like Jacopo Bassano’s “Lamentation by Candlelight” – a recent acquisition by SLAM – which shows mourners with Christ’s body just after its removal from the cross. Here, the candlelight, set against the impenetrable night, gleams off of Christ’s exposed flesh. Slate would continue to be a popular choice for nocturnal subjects well into the Seventeenth Century – as, for example, in Alessandro Turchi’s “St Peter and an Angel Appearing to St Agatha in Prison” (1640s), and numerous other themes, ranging from the afterworld and limbo to the Nativity.

Soon artists explored the possibilities of other stone surfaces as well, including polished semiprecious stones. A quantity of such stone was newly available, thanks to emerging trade routes, as guest essayist Mario Casaburo explains in the catalog. Interesting and decorative stones became collectible in and of themselves and were frequently incorporated into architecture or specialized pieces of furniture. Table cabinets, discussed by Joneath Spicer in the catalog, were particularly popular among wealthy individuals who also considered themselves students of science and the natural world. For instance, Johann König’s double-sided painting on alabaster – “Israelites Crossing the Red Sea” on one side and the “Last Judgment” on the other – was created as an exterior panel for a cabinet that held the treasured natural specimens belonging to the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus (1594-1632).

“Israelites Crossing the Red Sea” (recto) by Johann König (German, 1568-1642), 1625-31; oil on alabaster; 20 34 by 21 14 by 1 inches; Gustavianum, Uppsala University Museum, Sweden.

König’s work demonstrates the exciting pictorial opportunities that figured stone offered. The irregularities of the alabaster panels become waves crashing over the Egyptians or clouds of smoke consuming the Damned; similar mineral blooms, also in alabaster, become a kind of aura of holy light in Antonio Tempesta’s “Annunciation to the Virgin Mary,” as the angel Gabriel appears before Mary and asks her to bear the son of God. Color was often an important element. Lapis lazuli’s deep, almost luminescent blue and natural gold flecks provide a starry night sky behind the Holy Family in Jacques Stella’s “Rest on the Flight into Egypt,” with striations of white suggesting moonlight cloud formations. Similar irregularities also feature in Cavaliere D’Arpino’s “Perseus Rescuing Andromeda,” with the fractured blue of the lapis appearing as sky behind the hero Perseus and as sea beneath the hideous Krakon. A vein of blue pierces the stone onto which Andromeda is chained, and her toes cling to that fragile edge, stressing to the viewer, as Mann says, “the idea that Andromeda is on one side and the devouring monster is on the other side of the crack.”

D’Arpino also painted nearly identical versions of this scene on canvas, panel and copper, but stone connects to the story in a way that other materials could not. Andromeda is literally chained to the rocks as a sacrifice to the gods, and the mineral inclusions of the lapis, in part, become that actual stone in d’Arpino’s painting. Further, in Ovid’s version of the story, which Mann says would have been the most familiar one at the time, Perseus at first mistakes Andromeda for a marble statue due to the perfection of her form. The irony is that he carries in his hands the power to turn people into statues: the head of the Medusa, which will turn to stone when anyone who looks upon it (indeed, this is how he ultimately defeats the Kraken). Stone therefore plays the most essential of roles in this story, itself captured here in stone, at a key moment where chill marble is poised to come to life and animal rage is soon to become petrified.

“Rest on the Flight into Egypt” by Jacques Stella (French, 1596-1657), n.d.; oil on lapis; 4-5/16 by 3¾ inches; private collection.

That deeper understanding of how stone creates a dialogue with the content of the work, Mann says, came in a kind of “revelatory moment” for her. During her research travels – and the research has been going on for more than 20 years, ever since SLAM acquired the lapis “Perseus Rescuing Andromeda” in 2000 – Mann visited the church of Santa Prassede in Rome, which has an altarpiece, painted on stone, of Christ carrying the cross. “He is just weighted down by this heavy cross,” she says. “When you think of it being on stone it really made that a very physical feeling.” However, she adds, “in the context of the chapel, above it there is an image of Christ rising from the tomb, and then there is an image of Christ going up into to heaven – you really had this physical sense of release, of elation, it was really quite powerful.” This idea leads us back to the “Lamentation” by Bassano – that sense of chill, heavy, lifelessness not only pervades Christ’s body but also, Mann says, stands in for the stone upon which his body was prepared for burial. Christ himself was said to be the cornerstone of the church, and such theological connotations would have been foremost in the minds of the faithful during the Counter-Reformation.

Not all paintings on stone were explicitly religious works. In Southern Europe, Catholicism was inflected with neo-Platonist philosophy, and their blending can be seen in works like Alessandro Turchi’s “Will, Intellect and Memory,” with visual and conceptual roots in the imagery of the classical Three Graces, the Christian trinity, and the emerging study of aesthetic philosophy. Another painting with three figures is attributed to the Flemish painter Lucas Heere and is thought to depict three “favorites” (possibly lovers) of France’s King Henry III, all of whom had died in his service. In both these works, the stark blackness of the unpainted stone background (marble for Turchi, slate for Heere) create, in Mann’s words, an effect that “causes figures to almost come out of the void of the picture.” Mann writes in the catalog that in Turchi’s deeply philosophical painting, “the figures appear to float on its [polished] surface.” Perhaps, she adds, “the intention was to dislodge them from the physicality of the world and launch them into the realm of thought and contemplation.”

There are somewhat more earthbound works on stone in the exhibition, too. Just as the Protestant Reformation had spurred a renewed engagement with faith and scripture, it also opened up new possibilities for art based in the scientific and secular worlds. In the exhibition, two works that are both on marble and of marble – a still life on a marble ledge by Gerard van Spaendonck and the interior of a marble church by Wilhelm van Ehrenberg – are delights for the eye, a kind of visual pun. But the marriage of surface with story seen in works like “Tempesta’s Annunciation” is really the strength and the focus of the exhibition. How better to visually represent the blending of the material and metaphysical worlds that is the Annunciation than on this singular piece of alabaster? As previously noted, its concentric rings compositionally separate the realms of heaven and earth, with a ray of holy light passing between them. Beyond that, the very material of alabaster itself, with its translucent quality and associations with funerary sculpture, somehow manages to symbolize both the purity of the Virgin Mary – which, like the stone, allowed light to pass through without damage – and the ultimate fate of the son she will bear.

The exhibition as a whole is an ambitious undertaking. Of the more than 70 paintings, the majority are international loans, many from private collections, each requiring their own set of negotiations during a time when overseas travel and shipping are unusually complicated (the show was originally planned for 2020 but postponed for pandemic-related reasons). Further, the works come with their own display challenges: many are reflective, making them complicated to light; several works must be displayed inside clear Plexiglas boxes to protect them from visitors’ curious hands; and on the whole, they are quite small, making the hanging of the show a complex aesthetic feat. Mann jokes that it could be a challenge to avoid having the object labels be three times the size of the objects themselves. “We’ve chosen our words very carefully,” she says, “but we’ve tried to bring out the richness, because to me that’s what this show is about.”

The St Louis Art Museum is at 1 Fine Arts Drive. For more information, 314-721-0072 or www.slam.org.