“Snake Man” by Victoria Mamnguqsualuk and Magdalene Ukpatiku, Baker Lake, 1982, stonecut and stencil, ink on paper, 7/50. Robert and Judith Toll Collection. Luc Demers photo. Photo courtesy The Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College.

By Kristin Nord

BRUNSWICK, MAINE — Located among a stand of mature pine trees, the contemporary John and Lile Gibbons Center for Arctic Studies and the timber-framed Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum make a forward-looking statement among the more traditional stone buildings on Bowdoin College’s New England campus. The museum, named for legendary explorers and Bowdoin graduates Robert E. Peary (Class of 1877) and Donald B. MacMillan (Class of 1898), had a slow opening last spring but is already gaining notice for, among other things, the ways in which the staff has committed themselves to telling the Arctic story in all of its complexity.

Bowdoin students and faculty began traveling north to study Arctic cultures in 1860 and interest intensified with the repeated expeditions of these two alumni. The college opened the museum in 1967, and, in the 1980s, established the Russell and Janet Doubleday Arctic Studies Center, which underwrites anthropological, archaeological and geological research that builds upon Peary and MacMillan’s discoveries. Over the decades, Bowdoin has amassed collections that include not only MacMillan’s expedition equipment, films and photographs, but also an impressive collection of Inuit art.

“We have loved welcoming visitors to our galleries, be they researchers, undergraduates, Arctic visitors, school children on a tour or visitors taking advantage of a rainy day to explore the museum,” Genevieve M. LeMoine, a working archeologist and the museum’s curator/registrar, writes in the institution’s introductory literature.

Skeletized walrus tupilak by an unidentified Inuk artist, Kulusuk Island, circa 1970. Image credit 10754. Museum purchase. Photo courtesy The Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College.

Whether learning about Peary’s North Pole expedition of 1908-9, seeing his custom-designed sledge or delving into the journals kept by the SS Roosevelt’s chief engineer, the holdings in this museum are extensive and compelling, from its collections of artifacts to its well-tended photo archive, which has been digitalized and is now available online.

Currently on view is “Northern Nightmares: Monsters in Inuit Art,” a show curated by LeMoine and designed to appeal to art lovers and adventurers alike.

“The landscapes and seascapes of the Arctic appear bleak and barren to those unfamiliar with the region, but Inuit know that they teem with life,” LeMoine writes. It can be hard get one’s head around the symbolism embedded within the abstract Inuit carvings, prints and drawings; it’s a reminder of how foreign this culture and its values remain.

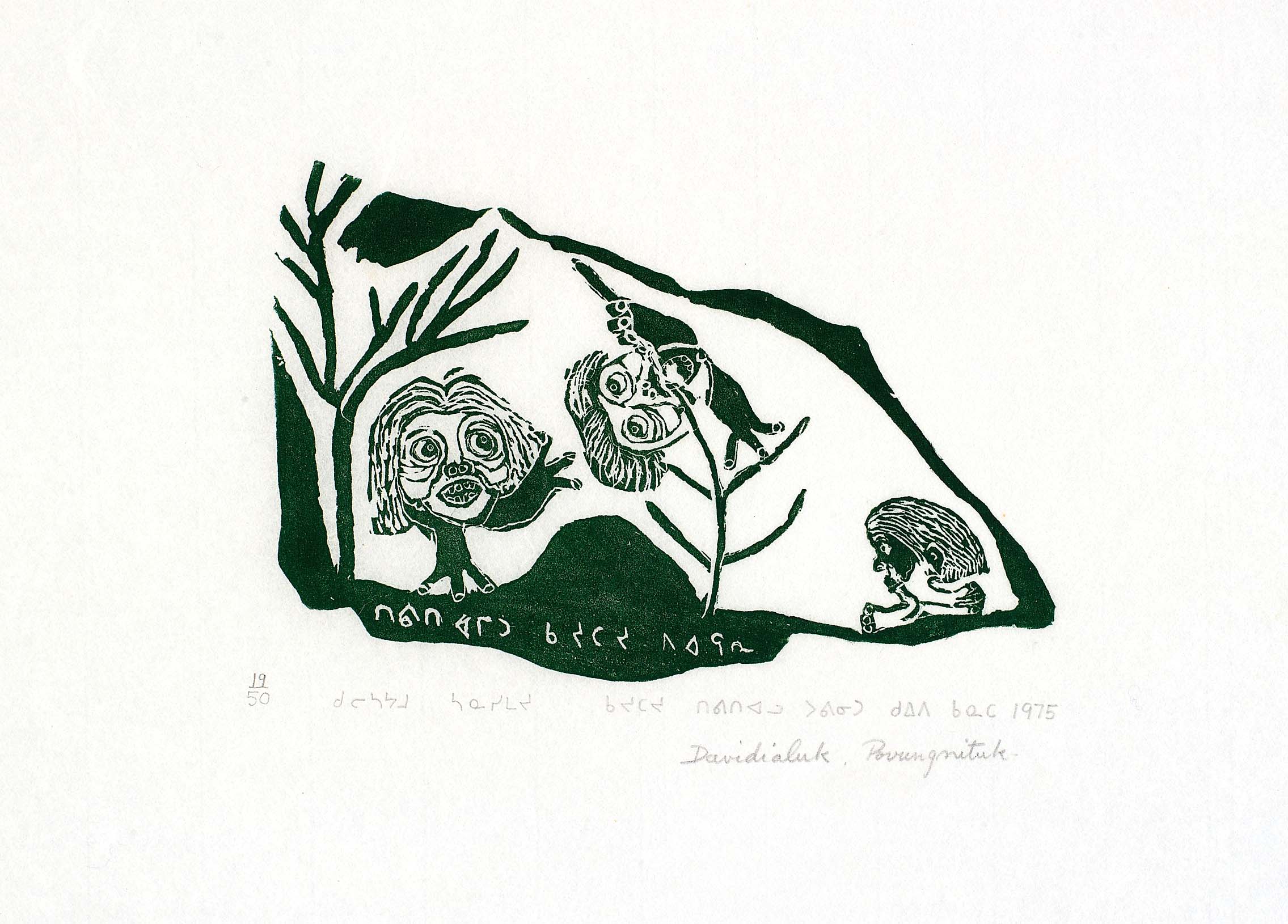

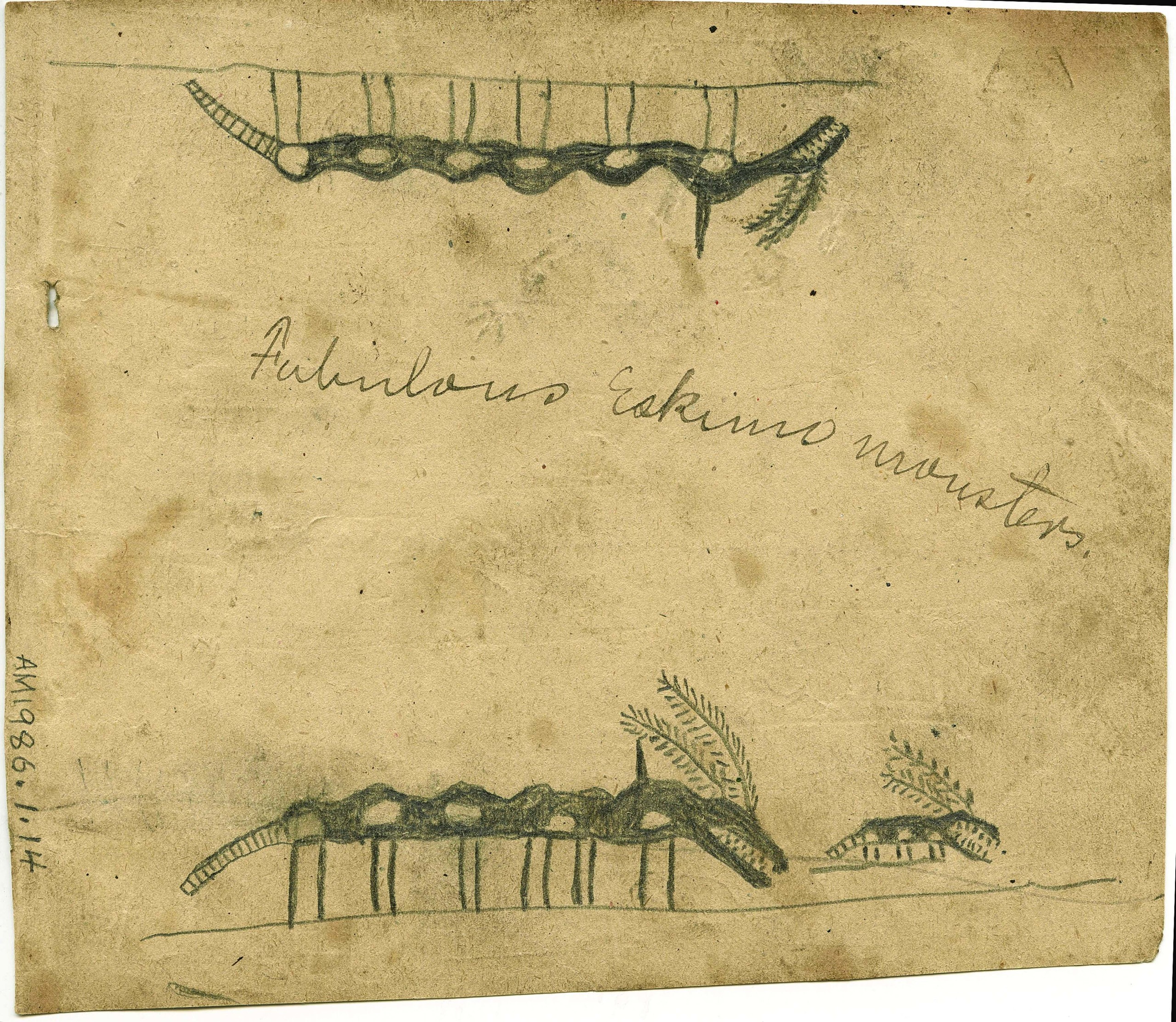

“The many varieties of humans, humanoids, spirits and transformations that appear in Inuit mythology and experience are not easily systematized,” Nelson H.H. Graburn agreed, in his essay, “Man, Beast, and Transformation in Inuit Art and Culture,” which was published in Manlike Monsters On Trial; Early Records and Modern Evidence (edited by Marjorie Halpin and Michael M. Ames. 1980). Graburn continued, “Any attempt at definitive classification or analysis contains the possibility of violating the data, for the Inuit did not traditionally feel the need for neatness or logical closure in the many tales, nor did the multiplicity of individual experiences exclude considerable variation.” Graburn lumped monsters within what he calls a “non-opposite category of turngaks,” or “evil spirits,” which he further equates with “spirits” or “ghosts.” And in this exhibition are a good number of ghoulish ones. I was particularly drawn to the work, “Fabulous Eskimo Monsters,” which features a toothy lizard-like creature with many stomachs crawling on a bleak landscape on pairs of spindly legs.

“Fabulous Eskimo Monsters” by an unidentified Inupiat artist, Cape Prince of Wales, 1892-1893. Image credit 15661, Museum purchase, Thornton Collection. Photo courtesy The Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College.

Then there is “Palraiyup,” another monster, which lurks in shallow water, ready to devour people who venture near the water’s edge; it has a particular preference for kayakers, and Inuit have been known to paint its likeness on their kayaks to keep it at bay.

Levi Kudluarlik and Sabina Qungnirq Anaittug each depict hunters engaged in battle with monsters distinct for their oversized heads and upraised arms. Alec Lawson Tukatuck brought to life a folkloric fable of “How Fog Came to Be.” Luke Iksiktaaryuk and Barabus OOsung conjured creatures in stone and in ink on paper, but in these instances the giants are kindly, and able to come to the aid of people.

Tunnituaqruk and Karjutayuuq are female and male versions of the same monster — though the female has breasts on her cheeks for children to suckle. They lurk in abandoned houses ready to break through the walls of igloos to devour the occupants.

There is a spirit man and a creature called an “eggillit,” a half-human, half dog apparition that uses its superior sense of smell to track and hunt prey.

Installation view of “Northern Nightmares: Monsters in Inuit Art,” at the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum through May 4. Photo courtesy The Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College.

Front and foremost is the seemingly ubiquitous “tupilak,” a malevolent spirit brought into being by a magician who released it with instructions to kill its enemies. In the early Twentieth Century, Tunumiit (east Greenland Inuit) artists created these objects and they became a favorite souvenir marketed by the Greenland Trading Co., and sold to American soldiers stationed in Greenland during World War II.

Artists have continued to innovate with tupilak carvings, LeMoine noted, using caribou antler instead of sperm whale teeth to cater to contemporary tourists. And, along the way, the tupilak has shucked its loathsome persona and become a protective spirit. Talk about a makeover.

From monsters, it’s just a few steps away to encounter two other exhibitions that further this story and focus on the museum’s historic artifacts by spotlighting gems from its major collections. This is where you’ll see the sledge that carried Peary to the North Pole in 1909 and be able to inspect the stunning Inuit workmanship on a sealskin parka. There is a “smart buoy” that is used by the Inuit to determine if the sea ice is safe. And, a remarkable collection of images zero in on Arctic culture historically and now.

“Standing Tupilak” by an unidentified Inuk artist. Gift of John P. Kline. Photo courtesy The Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College.

Acknowledging obvious biases (“we are currently an all-white permanent staff at a predominantly white institution of higher education”), the museum’s mission statement goes on: “The idea of the modern museum itself, as originally conceived, is a racist, colonial enterprise, and our particular museum is named for and owes its origin to two individuals who operated within colonial and racist frameworks.” It is the job of modern day curators and historians to place historical documents within context, while also presenting a fuller picture of the indigenous people who continue to live there. As LeMoine has written, “Vistas are simultaneously beautiful and daunting to southern eyes. But look closely, as Robert E. Peary did, and you will see a welcoming home where Inuit families have thrived for generations. Inuit continue to raise their families in the Arctic today, while navigating the dual threats of colonialism and global warming.”

Filling in the gaps in the Arctic story has become both a challenging and an exciting effort, fueling a number of exhibits from 2000 on, and leading to the publication of Peary’s Arctic Quest, co-written by the museum’s director Susan D. Kaplan and LeMoine. Other initiatives, LeMoine said, have included installing an inuksuk or cairn (by elder Piita Irniq), enlisting Noah Nochasak to reconstruct the museum’s 1891 Nunatsiavut kayak, as part of the exhibit “Kajak!” And it has mounted an exhibition of Inuk photographer Brian Adams’ eye on contemporary Inuit culture. A project focusing on the museum’s collection of Inuit embroidery is in the works. LeMoine said although there is no official Arctic studies major or minor, she typically works throughout the year with a small number of students on hands-on projects revolving around the collection.

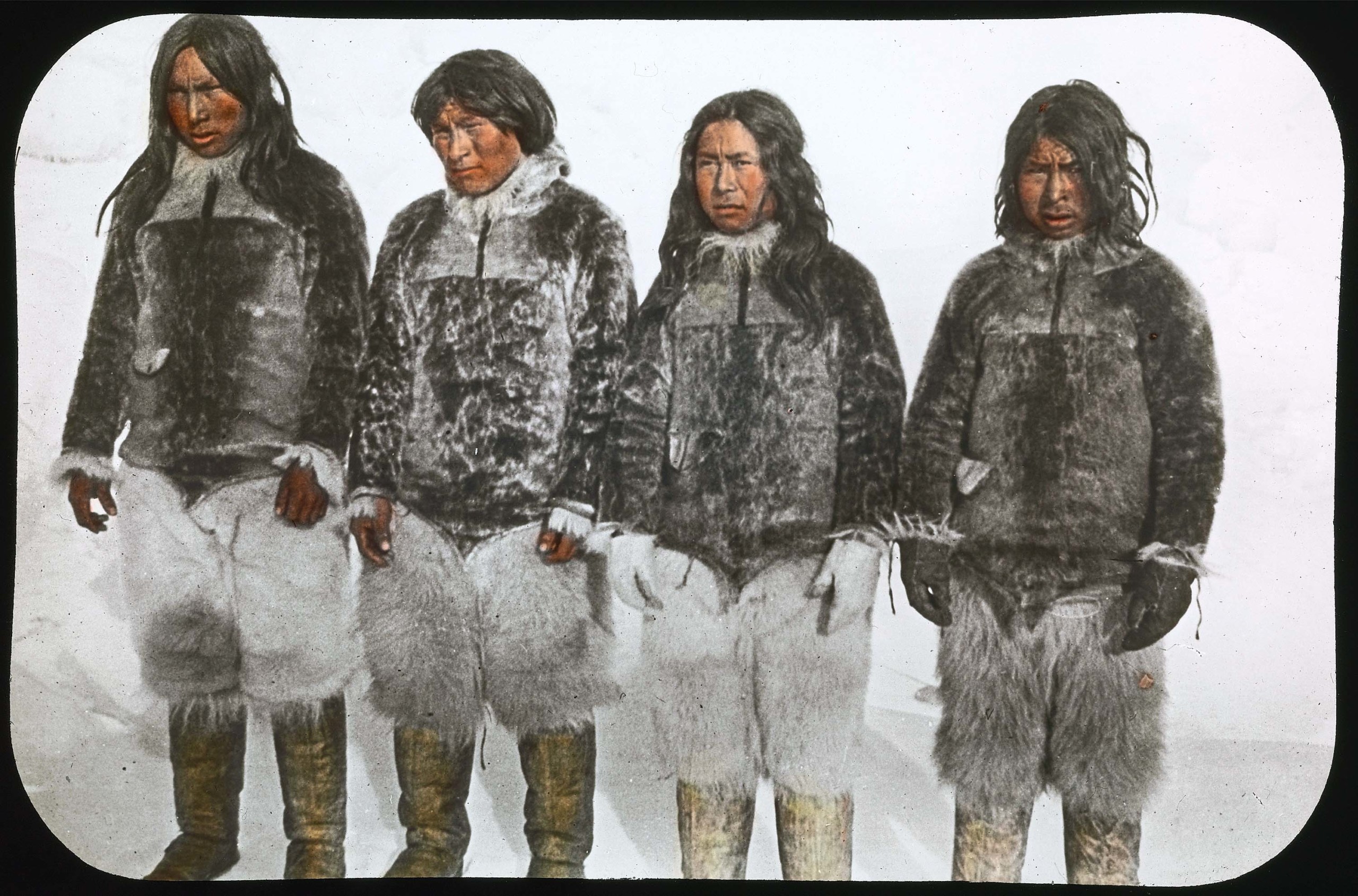

“Four Eskimos [Inughuit] at the Pole, Seegloo, Ootah [Odaq], Egingwah, and Ooqueeah [Higdluk, Ûtâk, Íggiánguak’ and Úkujâk]” by Matthew A. Henson, unidentified location, April 1909. Image credit 14973. Gift of Donald and Miriam MacMillan. Photo courtesy The Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College.

Life in the arctic on many levels is vastly different from Peary’s time, but it still has much to teach us.

“Although Peary succeeded in his life’s ambition to gain fame and recognition, paradoxically five of his expeditions failed and the final one remains in question,” Jon Turk wrote, in Cold Oceans, Adventure in Kayak, Rowboat and Dogsled, documenting the author’s own 1998 arctic adventure. The Inuit, for their part, were flummoxed to explain why the race to the Pole was so important. Turk wrote, “But in Europe and the United States, people waited for news of their favorite explorers as closely as modern sports fans follow pre-game, game and post-game commentaries”; he further contends that Peary was a great explorer, living and learning from the Inuit and traveling thousands of miles across the ice by dog team.

Not too long ago, Turk found himself in Greenland, on a hillside where Peary had sat, “in the middle of my own expedition, in which all those stories and boyhood dreams aligned themselves into a chronicle. I had failed repeatedly, like Peary. Finally, I succeeded, like Peary. But how could he have walked away from the North to become a desk officer and a socialite?”

“Spirit and Man with Harpoon” by Levi Kudluarlik, Pangnirtung, 1982. Image credit 47740. Gift of Barbara Lipton. Photo courtesy The Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College.

Such questions may linger in the mind of modern-day explorers and yet they still have much to learn from Peary, beginning with the skills and perspicuity his behind-the-scenes preparation brought to the plate.

From this museum visit, you may come away galvanized to act in some fashion. With the consequences of climate change already playing out before us, the Arctic is our canary in the coal mine. It is time to learn and listen.

“Northern Nightmares: Monsters in Inuit Art” is on view until May 4.

The Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum and John and Lile Gibbons Center for Arctic Studies are at 10 Polar Loop. Museum hours are Tuesday-Saturday, 10 am to 5 pm, and 1-5 pm on Sundays. For additional information, www.bowdoin.edu/arctic-museum or 207-725-3416.