Taking the sale’s top lot at $187,500 was the “Thunder Table,” produced by Wharton Esherick and commissioned by the Hedgerow Theatre. Esherick created the oak table in 1929 in the same year his daughter performed in the company’s production of Thunder on the Left.

Review by Greg Smith, Catalog Photos Courtesy Freeman’s

PHILADELPHIA – A multi-department effort combining material in Americana, Twentieth Century Design and Books & Manuscripts funneled 170 lots into Freeman’s Pennsylvania Sale on October 28, an auction of all-things iconic from the Keystone State. The sale went 90 percent sold and generated a gross total of $1,314,000.

Highlights were found from all three departments, but far and away the strongest results came in the form of Twentieth Century design from craftsmen Wharton Esherick and George Nakashima.

The offerings were bolstered by 12 important Esherick commissions from the Hedgerow Theatre in Rose Valley, Penn.

“We’re very pleased with the results for the collection,” said Twentieth Century design department head Tim Andreadis. “It was the highest price ever achieved for a collection of Esherick works. His years at Hedgerow were artistically important for him, he and the theatre shared a vision, they were very much supporters of each other.”

Esherick began working at the theatre through mutual admiration with its director, Jasper Deeter. He would work on set design, costumes, lighting and original posters for the productions, most of which have been lost to time. As his children grew, they began to take part in the productions.

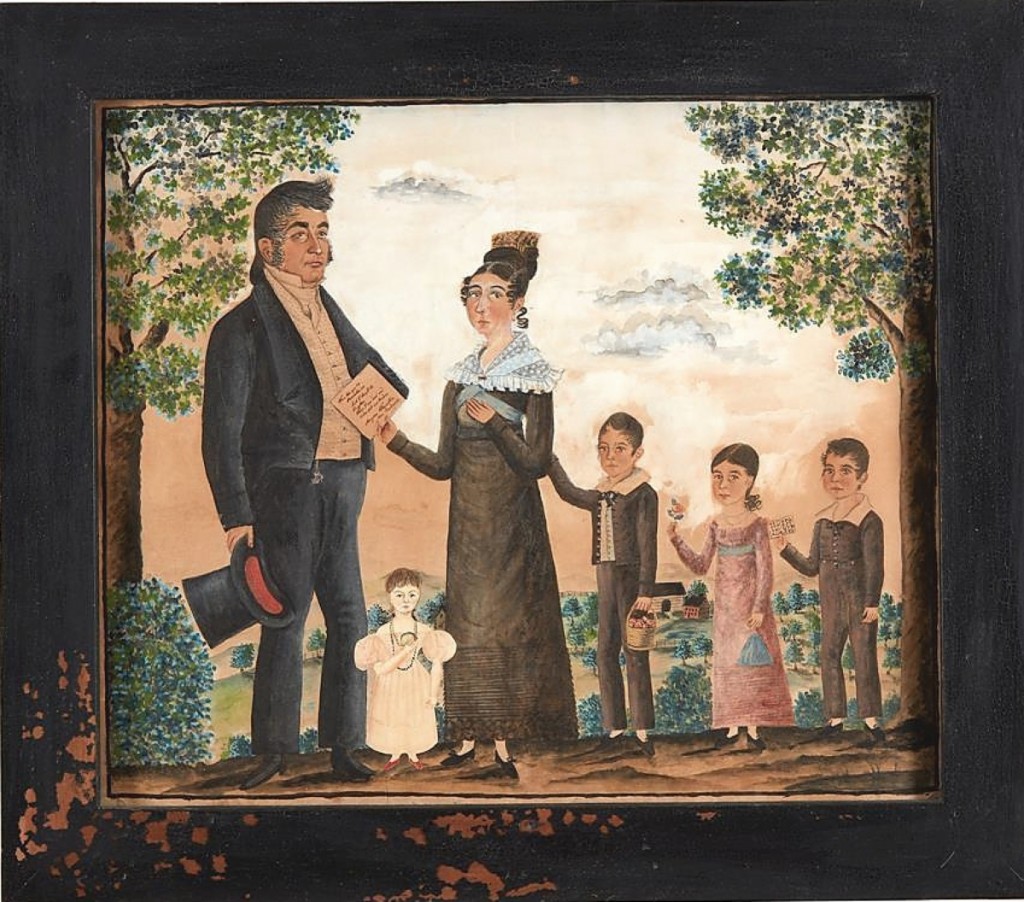

Attributed to Jacob Maentel, this watercolor and ink paper family portrait took the second highest result in the sale, selling for $106,250. It depicts the Kitzmiller family of Littlestown, Penn.: father John Michael, mother Mary Ann and their children seen right, Eli George, Honoria Elizabeth and Zubulon John. Seen between them is a late addition to the family, Louisa Maria Christiana, who was added later as an applied cutout by Maentel when the parents had her 14 years following their next youngest. In the mother’s hand is a note that reads “When this you see Remember Me Lest I should be forgotten, When I am dead and under foot and trodden. Mary Ann Kitzmiller, their mother.”

“Some of Esherick’s best known sketches and sculptures used Hedgerow as a jumping off point. He would spend hours sketching the actors on stage from the balcony, studying movement and dance and how they were expressing emotion,” Andreadis said.

Renowned among them is his sculpture “The Actress,” originally carved in cherry and later cast in bronze. It is based on his daughter.

The sale’s 12 Esherick lots represented everything the theatre had left, many of its works over the years departing as keepsakes or gifts for those who acted or supported its mission. All proceeds from the sales are earmarked towards rehabilitating the Hedgerow Theatre.

Chief among them was the “Thunder Table,” a trestle-style dining or meeting table in oak, 118 inches long, that sold for $187,500 to a private American collector. The table was named to mark the occasion of the theatre’s production of Thunder on the Left, a stage adaptation of Christopher Morley’s book of the same name. His daughter was in the production.

Tim Andreadis estimated that Wharton Esherick made fewer than a dozen staircases in his career, with two of them for the Hedgerow Theatre. A spiral staircase burned down in the 1980s, while this staircase shown, a painted pine example, sold for $81,250 to the Rose Valley Museum, which intends to install it in a gallery dedicated to the artist.

“Like many of the pieces he made for Hedgerow, it can be disassembled, that was something he built into the design,” Andreadis said. “Hedgerow being a working theatre, they were always moving things. A dinner table for the actors today was on stage tomorrow as a banquet table. Its documented use was in the theatre and also at the nearby Hedgerow Farmhouse Studio, which had a communal live/work arrangement with the theatre. They used the tables to eat, have meetings and draft scripts. If they needed to, they would move the table sometimes by disassembling it. That’s why the legs are hinged and can pivot, they can be folded underneath the top and it can be carried and reassembled.”

Selling for $81,250 was a painted pine staircase by the maker, one of two originally built for the theatre, the other having burned in a fire in the mid-1980s.

“Wharton made fewer than a dozen staircases in his lifetime,” Andreadis said. “The most famous being in his studio, but also for the Curtiss Bok commission and others. Anytime you’re talking about something that is site-specific or architectural, you don’t know if you’re going to have a buyer who has an intended use for it. We were pleased that there was a good bit of interest from folks who wanted to reinstall it.”

One thing that stands apart from many other Esherick works is that the staircase is painted and of pine. To this, Andreadis said, “We believe it was originally painted. Typically Wharton would have used harder wood, an oak or a chestnut. The staircase at his house is a white oak. All indications is that this was always a painted element. The actors would periodically spruce up the theatre and this is the type of thing that would have received a new coat of paint. They now have this beautiful worn look that you get from thousands of feet stepping on them and they have that swell to them and that gives character.”

George Nakashima made this English oak burl and rosewood Slab I coffee table in 1961. It sold for $37,500.

The buyer was the Rose Valley Museum, who intends to create a gallery of Esherick works. Over a period of nine months, the museum was able to raise $100,925 from 139 donors on a GoFundMe campaign in order to keep those pieces on exhibit in the area they were made.

The museum was also successful in purchasing two examples of Esherick’s hammer handle chairs, which remain an icon of his furniture output. Freeman’s sold eight chairs in separate lots and they brought anywhere from $8,125 to $17,500 each. The grouping was notable in that it included two examples from the earliest batch of hammer handle chairs he made, as well as examples from subsequent batches where the design is adjusted and refined. All of them were from the original 1938 commission of 36 chairs for the theatre. The chair’s final form, which he reproduced in some numbers in subsequent decades as the design grew in popularity among his clients, is based on the final batch of chairs for the Hedgerow commission. The chair dons its name from the source of its material: “Wharton Esherick purchased two barrels of hickory hammer handles, in two sizes, at an auction of assets from an out-of-business woodturning company….Esherick turned to the hickory hammer handles as source material for the chairs’ construction. Utilizing the longer handles for the chairs’ stiles and legs, and shorter handles for the seat rails and stretchers, the ‘Hammer Handle’ chair was born.”

“They were made over a series of three or four months in 1938, he made four different batches of them and with each batch, he refined the design to move a stretcher or connect the rear stiles,” Andreadis said. “We had at least one chair from every version. We had one from the very first batch that looked quite experimental, and then one from the final iteration where the backsplat is wider and lower, and the stiles are wider and splayed. It’s something he learned from trial and error, he was figuring it out as he went. Over the course of these four batches, he arrived at the prototype for the later ash chairs.”

The sale featured 26 lots from New Hope maker George Nakashima, led by a $46,875 result for a 1976 Conoid Bench in American black walnut and hickory. From the same consignor and also of the Conoid series was a set of four dining chairs, circa 1963, which brought $15,000 and a dining table from the same year that sold for $20,000.

Lynda Cain said this painting by Joseph Wright, an American painter who worked as an engraver for the United States Mint, documented the artist’s trip to an estate in England. The subjects are believed to be the Gribble family from Kenton and it is dated 1789. “It was just a great painting — a regal family with the palatial columns,” Cain said. The 47-by-35-inch oil on canvas sold to an English buyer for $27,500.

Still from Nakashima was an English oak burl Slab I coffee table dating to 1961 that sold for $37,500. A triple sliding door cabinet brought $42,250, while a triple chest of drawers took $35,000.

“The rarest of the designs was the music stand; George didn’t make a whole lot of them,” Andreadis said. “There weren’t too many pieces that he created that diverged from his standard designs. They were kind of serialized, standard forms that were in production for decades. But the music stand was a special piece, the consignor was someone who really loved music and the opera and had a musical background. This was in her music room next to her piano.”

The music stand, created in the last year of George’s life in 1990, was made of walnut and rosewood and sold for $18,750.

The New Hope craftsmen have become America’s greatest and most valuable design export of the Twentieth Century, prized for their originality, detail and quality, which remains elevated above and in stark contrast to much of the modernist designs that were mass-manufactured and produced in the United States around them during the designer’s lifetimes.

“We have pieces that are going to Asia and several European countries,” Andreadis said. “It’s been interesting watching the trajectory of Nakashima’s market, particularly with the past five years or so, the Europeans have become more interested in George’s work. It’s surprising that it took as long as it had, but George was a student of Corbusier and was very much involved in contemporary architectural and design movements in the 1920s and 30s and 40s and was very much influenced by them. He lived in Paris for a time and also India. George was really a global man who had a tremendous ability to draw upon the influences of his life to create a body of furniture that were works of art. New collectors emerge in just about every one of our sales, people who we’ve never heard from or have been waiting to buy a special work by George. We’re always pleased to see that, it’s not the same cast of characters buying in every auction. New buyers seem to emerge all the time.”

Here we are able to see the subtle differences between Wharton Esherick’s first batch of hammer handle chairs and his fourth batch, which he would base all subsequent editions off of. Both are from the 1938 Hedgerow Theatre commission, where he created 36 examples. The left is the earliest, with differences visible in the location of the joints as well as the stretchers. In the example on the right, he widened the seat by three inches and tapered the stiles inward to cradle the body. The example on the left took $10,000, while the right brought $17,500.

Dropping back to the early Twentieth Century were 11 lots from one of America’s greatest ironworkers, Samuel Yellin. Andreadis said many of them came from the Yellin family’s private collection of works.

Leading the group was a circa 1930 floor lamp with painted shade depicting a charioteer on one side and a dog running between two trees on the other – it sold for $22,500. A table lamp with a spiraling iron stem and a mica shade sold for $8,125.

Taking $15,000 on a $1,200 high estimate was a 14½-by-12¾-inch iron plaque bearing a lion in relief with the stamped and engraved signature “SY,” circa 1908-12. Yellin only arrived to Philadelphia from the Ukraine in 1905, making this an early work.

Said Andreadis, “One of the things you don’t get from the photographs is that its in three-quarter-inch steel, a really thick thing. The lion is quite proud from the surface of the surrounding metal, the whole thing is done on a forge, they really manipulated the metal.”

He said the signature with the two letters is a rare early signature for Yellin, something you don’t see often.

For his harnessing of fire, Yellin earned the nickname of “the Devil with a hammer in his hand” during his lifetime, and that was referenced in a 1930s copy of Howard Haggard’s Devils, Drugs, and Doctors: The Story of the Science of Healing from Medicine-Man to Doctor, with an inscribed 1933 note from Yellin’s associate Dayton E. Froelich, that read “To Mr Samuel Yellin, the ‘devil’ at the forge, with my best wishes for his health and prosperity in the coming year.” It took $125.

Also of note from Yellin was a wrought iron and chestnut top table from his Arch Street studio that sold for $13,750. Freeman’s had an archive photo featuring him and others working at the table.

An early work for Samuel Yellin, dating around 1910 and bearing his initials of “SY,” this lion with chase and repoussé work was executed in three-quarter-inch iron. “It had the sense of a student work to it, a catch piece for a larger commission, maybe trying out a design,” Andreadis said. “Everyone was really attracted to it. Anytime buyers notice something they haven’t seen before, it tends to attract a lot of attention. You wonder if this was something he made for his own amusement or if it was something he used to teach.” Measuring 14½ by 12¾ inches, the work sold for $15,000.

“There’s not a lot of Yellin furniture out there to begin with,” Andreadis said, “but to have something that he made at the shop for use there, that’s a special thing.”

Moving to works from the Nineteenth Century we find a watercolor and ink on paper portrait of the Littlestown, Penn., family of Mary Ann and John Michael Kitzmiller and their children, attributed to Jacob Maentel, which sold for $106,250.

Lynda Cain, department head for American furniture, folk and decorative arts, told us that the work came from a private collection where it was the “pride and joy.”

“There aren’t too many with the whole family; this is one of the larger groups,” Cain said. “There’s something compelling about it. I love Mr Kitzmiller, you can see how confident he was with his expression – very full of pride. And the way the children were rendered, the eldest son holding onto his mother’s arm, it was incredibly appealing.”

The portrait featured a note in the mother’s hand that read “When this you see Remember Me Lest I should be forgotten, When I am dead and under foot and trodden. Mary Ann Kitzmiller, their mother.”

Also notable in the portrait was the overlaid addition of a fourth child standing between the parents, whom they birthed when the others were older. Cain said she believed the addition was also by Maentel. Both of John Michael Kitzmiller’s parents, John George and Anna Christiana Kitzmiller were separately painted by the artist in a known double portrait that was exhibited at the Historical Society of York County in 1944.

Highest among the works from George Nakashima was this Conoid Bench in American black walnut and hickory that sold for $46,875. The same consignor’s estate offered up a dining table, $20,000, and four chairs, $15,000, from the same series but mostly different years. She also held the Nakashima music stand separately pictured.

In other notable lots, Cain pointed towards a silver-mounted oak walking stick that brought $11,250, over five times estimate. The silver top was engraved, “A piece of one of the girders of Independence Hall/ Phila – built 1721/ Jacob W. Colladay to his brother J.L. Colladay 1855.”

A Chippendale carved walnut tall chest from Philadelphia or Chester County and dated 1773 sold for $15,000. It featured its original rococo fire gilt brass pulls and was marked in ink to a dust drawer “Jesse Hutton his hand and pen 1773/ Jesse Hutton made this draw in the year of our Lord 1773” and marked in chalk with a Quaker star. It sold to a private collector.

Selling for $4,063 was a circa 1875 ebonized three-door cabinet from Philadelphia maker Daniel Pabst. The piece featured carving in relief to many elements and was fitted with enameled ceramic tile profile portraits of William Shakespeare and an unidentified gentleman.

“There is a close version to this at the Brooklyn Museum,” Cain said. “Pabst scholars came in just to visit the piece. It’s been known to have existed by this group and it was very interesting to hear them talk about it.”

Pabst worked for Frank Furness and other architects and is among the masters of Victorian-era casework and furniture, at one time employing up to 50 people in his workshop. None of the firm’s papers survive today, but his pieces can be found in many major museum collections, the Philadelphia Museum of Art with the largest collection of his works.

From the books and manuscripts department came a 1775 Map of Pennsylvania Exhibiting Not Only The Improved Parts Of That Province, But Also Its Extensive Frontiers by William Scull, which took $5,000. Freeman’s said that when it was made, it was the most comprehensive and detailed map of the state and was used by both British and Colonial forces during the Revolutionary War. It was an updated version of Scull’s 1770 map.

Not many music stands were made by George Nakashima, this 1990 example was commissioned from the maker and sat next to the consignor’s piano. In American walnut and rosewood, it sold for $18,750.

Originally made for the detection of fake currency, a Fractional Currency Shield, circa 1866-69, sold for $4,688.

A single leaf page of The Pennsylvania Journal and The Weekly Advertiser, dated October 11, 1775, brought $3,500. It featured an iteration of Benjamin Franklin’s famous cartoon of a segmented snake with the states around it, originally created to comment on Colonial disunity in the French and Indian War. By 1775, the comic was appropriated with the words “Unite or Die” to unite the colonies in resistance to the British government.

When the sale first began over a decade ago, Lynda Cain said it numbered to more than 400 lots.

“Over the last couple of years, we’ve tried to make them a bit more focused,” she said, “raising the floor a little bit, they’ve become more curated. They’re more manageable, you can focus on things more clearly.”

For additional information, www.freemansauction.com or 215-563-9275.