By Cynthia Beech Lawrence

DOWNINGTOWN, PENN.- The year was 1735. On May 20, in Kingston, N.H., a young boy named Parker Morgan died after a few days of sickness. Parker was patient zero in an epidemic of seemingly biblical proportions that was to terrorize colonial New England.

“Throat distemper,” now known to be diphtheria, was a bacteria that destroyed tissue in the throat, nose and lungs, suffocating the patient. It was highly contagious and affected mainly young children. Of the infected, the death rates across the New England towns were estimated to be anywhere from 25 to 60 percent. For short periods in some towns fatality approached 100 percent. These estimates are necessarily crude as there are no statistics for the number who recovered. A concurrent plague of scarlet fever spreading from Boston with symptoms similar to the more-fatal diphtheria also may have diluted the number of fatalities.

Overall, between 1735 and 1740, 22 out of every 1,000 people succumbed to throat distemper. To the youngest generation of Americans, it was a new disease to which they had no resistance. The epidemic was to rage on for five years. It was feared the disease would destroy the colonies. The mystery of its spread and origin was explained variously as the result of a late spring, a plague of caterpillars or an angry God. In Puritan theology, death was God’s punishment for human sin. New England was already in the early stages of The Great Awakening, an intense religious revival, and the epidemic fueled the fervor. In 1738 a 17-page dirge was published about the plague, titled “Awakening Calls to Early Piety.”

Newbury, Mass., lay on the Old Bay Road that ran from Boston to Casco Bay, one of a string of small, isolated towns dotting the coast. With their own gardens and livestock, families could keep to themselves on their little farms, except for church and school. By 1735, every town with more than 50 inhabitants had its own public schoolhouse, and on the Sabbath, everyone attended church. Abigail Chase lived on one such farm with her parents, Moses and Elizabeth Chase, and her nine siblings, of which she was the youngest. Their farm was the eastern half of her grandfather’s original 100-acre homestead between the Bradford Road and the Merrimack River, in what is today West Newbury. Abigail’s parents and neighbors would have read in the Boston papers, or heard, stories of the approaching plague. The stories were not uplifting ones; some families lost all of their children, in others the children died so close together that they were buried in the same grave, and no one knew by what means the disease was spread. Newbury was only 15 miles from Kingston. “The strangling angel of children” loomed ever closer, descending the Old Bay Road from the north. At the same time, scarlet fever advanced from the south, the two plagues eventually meeting in Essex County in the autumn of 1735.

Essex County had just experienced an infestation of noxious caterpillars, so many that the roads became green and slippery as they were squashed and the bushes were stripped bare. It was theorized that decomposing caterpillars had infected the air. It was a time of misery and fear. More than 100 children were to die in Newbury before the end of the year. The Boynton family lost eight children, of which four were buried in a single grave. A Newbury doctor, John Fitch, set out to discover the cause or a treatment, fell ill and died of it. How Moses and Elizabeth Chase protected their family for so long is a wonder. The illness was all around them. It was not until May in 1736 that the epidemic found their door. When it did, it was devastating. Two year-old Abigail died May 15. Five year-old Rebekah died three days later. Anne, age seven, died nine days after that.

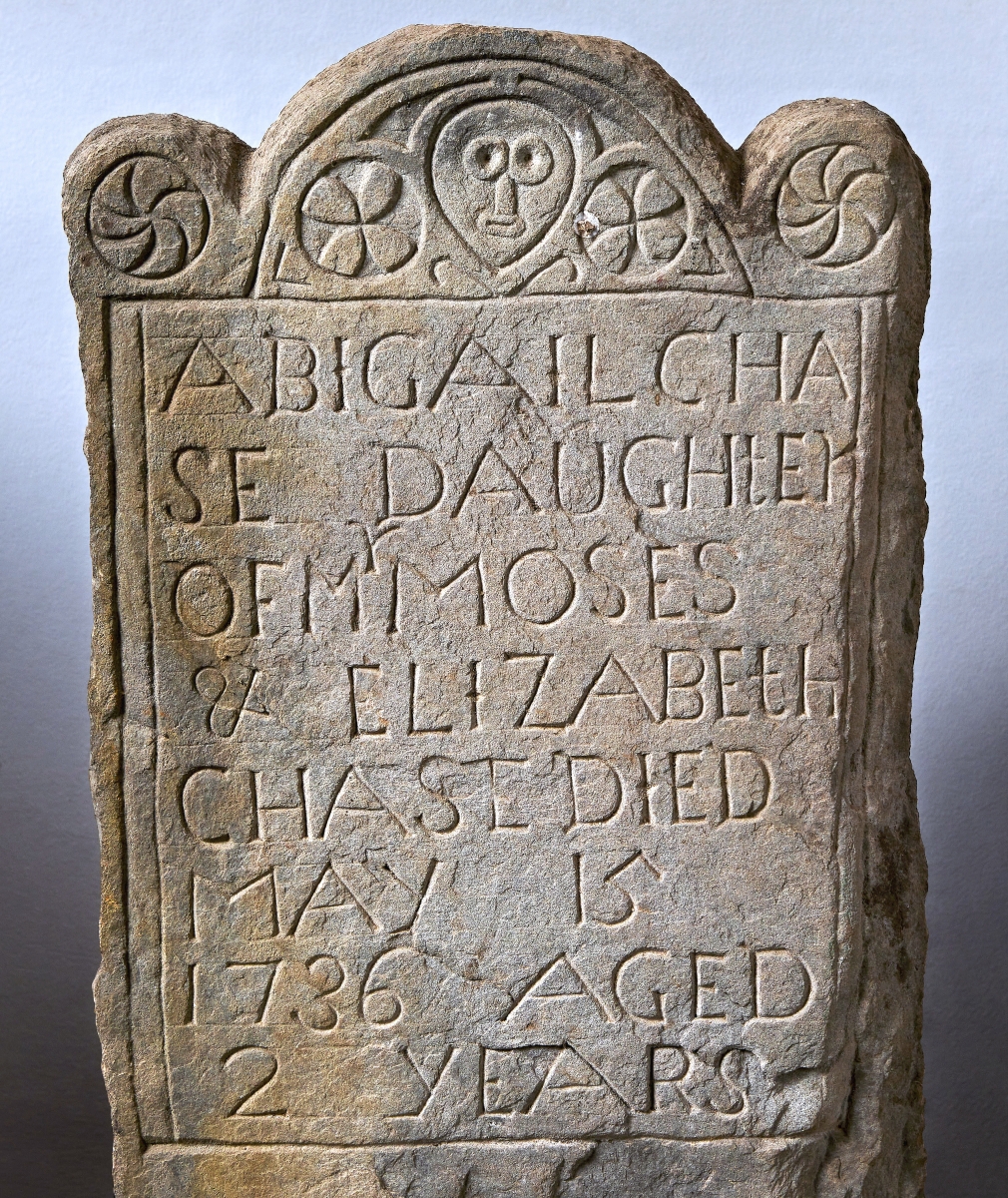

Moses and Elizabeth Chase buried their daughters in the family plot in Newbury’s Bridge Street Cemetery and ordered three little gravestones. There is no record of who carved the stones, but they look very much like those by John Mullicken (1690-1737), one of a family of carvers in Newbury. Along with his brothers, John learned stone carving from his father. Puritans rejected elaborate carving and decorations like crosses as too closely associated with Roman Catholicism. Death’s heads or skulls with wings were often used to symbolize the soul’s voyage through brief life and death. Remote learning led to a vernacular style for most carvers. Mullicken’s individual style was a folk art design with a mask-like face surrounded by rosettes and whorls. The stones marking the graves of the three little girls are of his style. Each stone is topped by a simple rounded tympanum and decorated with a friendlier death’s head having large, child-like eyes and small lips, perhaps to convey the soul of a child rather than an adult. The primitive simplicity of the grave stones and their purity of design reflected the innocence of those children killed so horribly by the epidemic.

Which is why, nearly 300 years later, on a cold February afternoon in an abandoned garage in Lebanon County, Penn., Ron Pook knew something was wrong. There, laying in the dirt and cobwebs, was something that should not have been there. Brushing aside some of the filth, he found the grave stone of Abigail Chase.

“I knew early on it wasn’t from around here. This stone had a great folk art presence. The beauty of these grave stones draws people to remove them, but it is a sacrilege that it should never happen,” Ron said. “I felt very strongly that the right thing to do was to return it. I knew someone would care about this grave stone. She was only two years old.”

But first Ron had to find out where it belonged. Once the stone was delivered to Pook & Pook Inc. in Downingtown, researcher John Burdumy investigated historical genealogy and cemetery databases until he identified the Chase family and Bridge Street Cemetery in Newbury. He found pictures of the whole family’s grave stones. Abigail’s was missing.

Ron Pook has been a member of the Berks County Association for Graveyard Preservation ever since he restored an ancient cemetery on his own farm. He wanted to return Abigail’s grave stone to its proper place, but needed to find out if there was a similar group in Essex County to help him. One call to the Museum of Old Newbury was all it took.

Susan C.S. Edwards, executive director of the museum said, “I was delighted to hear from Ron. Over the years we have had a couple of grave stones returned, but this is the first time a family will be reunited… Preserving Abigail’s grave stone is preserving her memory here in Old Newbury. We believe the stone may have been missing since the mid-Twentieth Century. The Abigail Chase stone is an important piece of American folk art and family history. Its journey back to West Newbury is nothing less than remarkable due to the outstanding efforts of Ron Pook.”

Through her connections, Susan arranged for Bridge Street Cemetery to receive the stone. Ron then bought it a one-way ticket on an antique shipper’s truck to Newbury.

“Abigail Chase died when she was only two years old. That grave stone was the only mark she left on this earth,” said Ron. “I am glad it will be returned to where it belongs, with her family, where people can see and remember her.”

Ron’s wish is being realized. Already, a handful of people at Pook & Pook and at the Museum of Old Newbury are aware of Abigail and her story, including this writer, who was surprised to discover that we share an ancestor. Aquila Chase (1618-1670) is both Abigail’s great-grandfather and my ninth great-grandfather. Without Ron’s discovery of her stone and the events he set into motion to affect its return, I never would have known of Abigail, or of her family’s tragedy and perseverance during the 1735 epidemic. I have since told my own family the story. The Museum of Old Newbury is planning a ceremony later this summer when the stone is unveiled at the Old Bridge Street Cemetery. All of Newbury will celebrate. And so, Abigail’s memory lives on.

For more information about Pook & Pook, visit www.pookandpook.com or 610-269-4040. The Museum of Old Newbury is online at www.newburyhistory.org or 978-462-2681.