“The Red Room, Étretat” by Félix Vallotton (Swiss, 1865-1925), 1899. Oil on artist’s board. The Art Institute of Chicago, Bequest of Mrs Clive Runnells.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

CLEVELAND – Museums are at last opening back up, offering long-homebound visitors a chance to finally look at a different set of walls. It is a coincidence, but an intriguing one, that the Cleveland Museum of Art will celebrate that phenomenon with an exhibition that offers an often uncomfortably close look at what home life can be – from sacred to suffocating. “Private Lives: Home and Family in the Art of the Nabis, Paris, 1889-1900” is on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) through September 19.

It was a “fortuitous coincidence,” said Heather Lemonedes Brown, deputy director and chief curator at the CMA and, with Mary Weaver Chapin of the Portland Art Museum in Oregon, co-curator of the exhibition. “For many people all over the world, home life became perhaps different, more concentrated, intensified.” She and Chapin “started talking about this exhibition long before we ever heard about Covid-19,” she clarifies, but even so, the works on view touch meaningfully upon the simultaneously comforting and claustrophobic feelings about home many have experienced during this time of pandemic: “both the pressures and joys of family life,” as Brown puts it.

Family is a key concern in the artwork produced by this group of painters, if not specifically in their stated artistic goals and purpose. They were known as the “Nabis,” a name that emerged from their shared interests after they coalesced as a group mutually influenced, in part, by the Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin. “Nabi” derives from the Hebrew word for “prophet,” chosen half-seriously, half-ironically to suggest that these young rebels were “prophets of art,” united in their desire to push against the “descriptive naturalism” (Brown’s words) being taught in the Paris art academies and promoted by the annual Salons. Their work varies – “it’s not that you could mistake one of them for the other,” Brown says, but they agreed on some shared principles. These include, as Brown writes in the catalog, “that a work of art was an enigma to be deciphered, that the purpose of art was to suggest rather than to tell, and that art should reflect the way things looked and felt to the artist.”

The Nabis were a diverse and somewhat fluid group with artists moving in and out of the inner circle over the course of the movement’s short life in the final years of the Nineteenth Century. Brown and Chapin chose to focus their exhibition on four artists – Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Félix Vallotton, and Édouard Vuillard – not only because they were central to the group’s dynamics but also because their work focuses specifically on the domestic interior. The artists do this in different and fascinating ways, each inspired by (and drawing subject matter from) his own unique household circumstances. Seen together, as in this exhibition, the artworks propose something like a spectrum of feelings about home and family that may provoke sympathetic responses in a range of viewers.

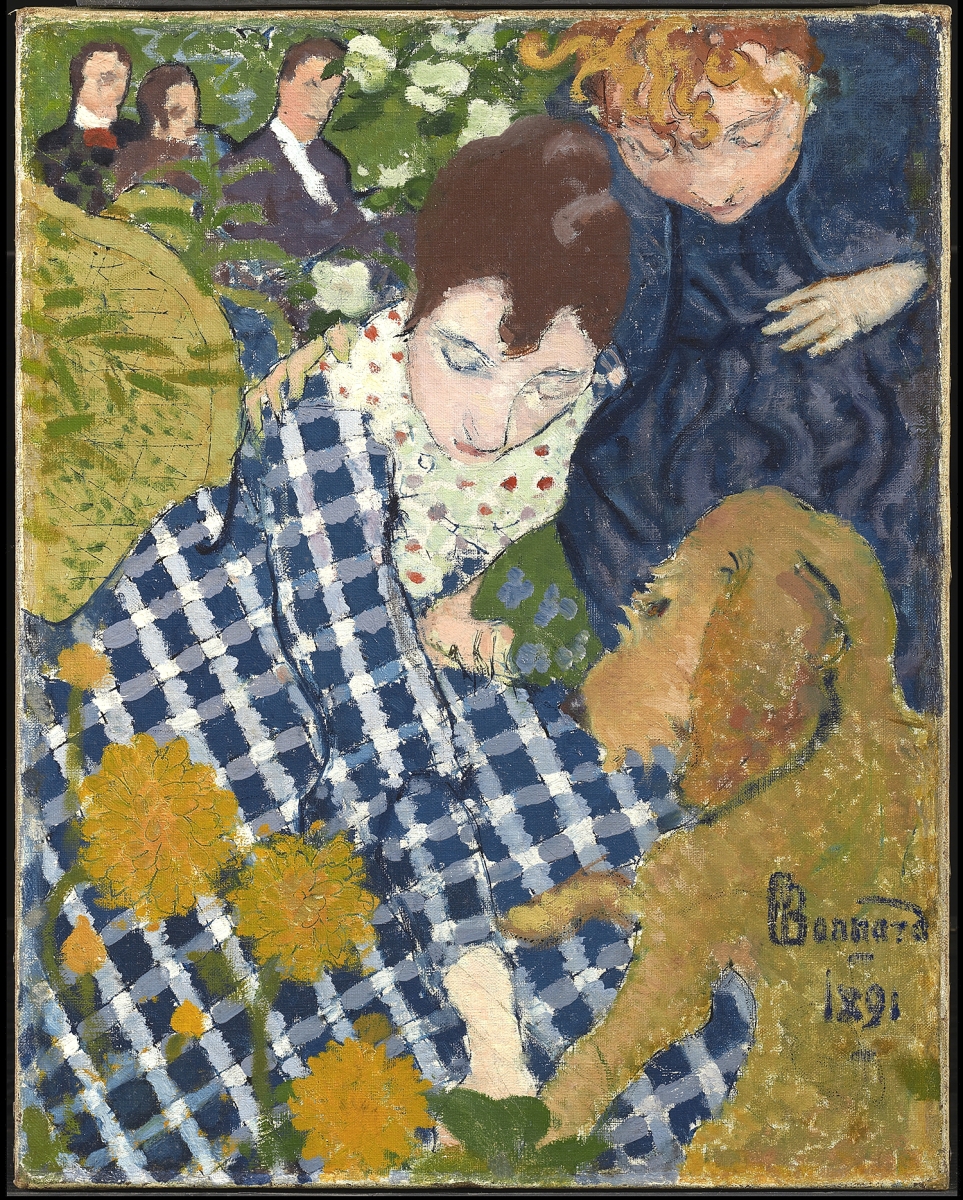

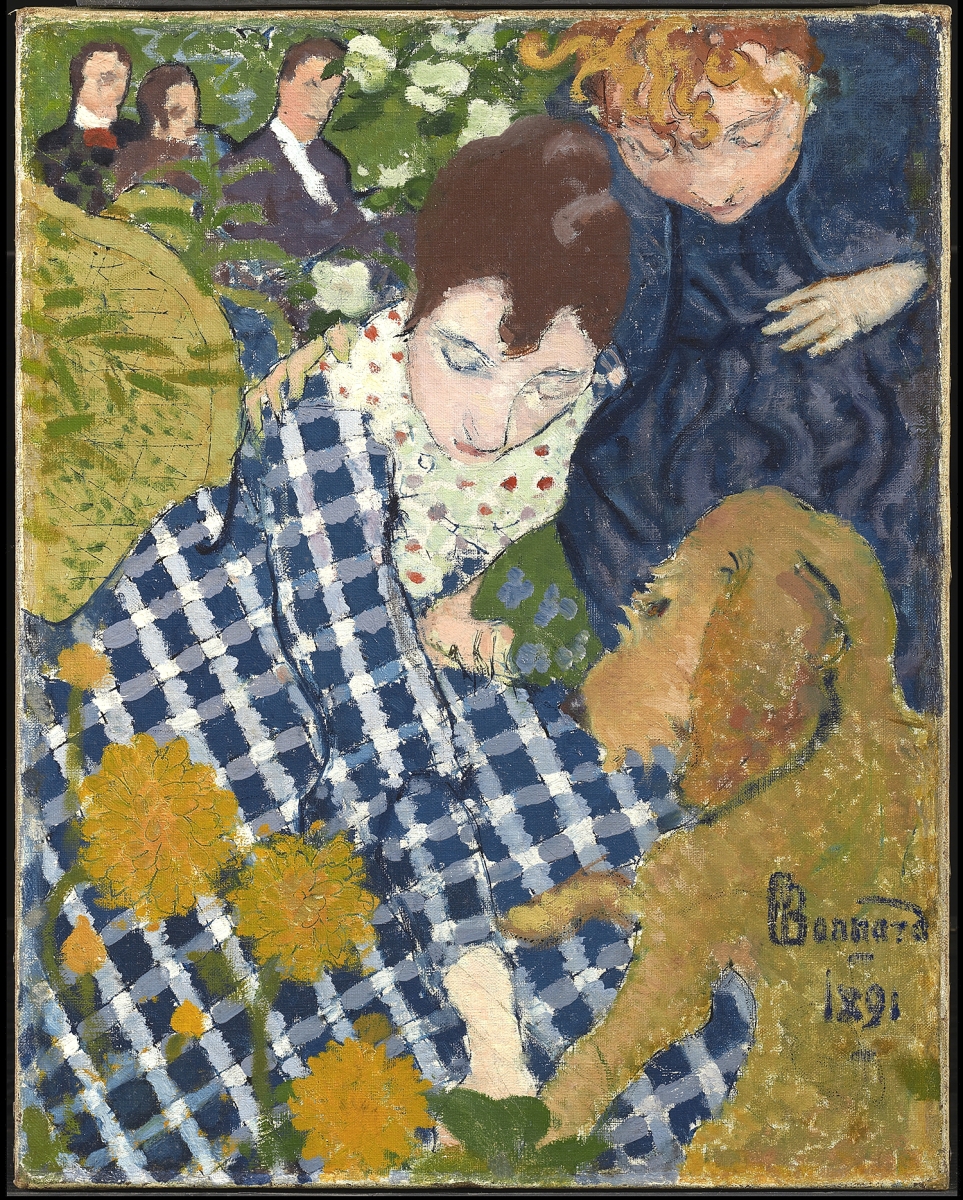

“Women with a Dog” by Pierre Bonnard (French, 1867-1947), 1891. Oil and ink on canvas. The Clark Art Institute, acquired by the Clark, 1979. Image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute. ©2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Denis, in works like “Washing the Baby,” valorizes the quotidian moments of home and family; influenced by his happy marriage and his Catholic faith, day-to-day tasks become like sacraments, his wife and baby stand-ins for the Madonna and Christ child. Bonnard also had a loving, lifelong partnership – if a somewhat less traditional one – but his extended family is the linchpin for his domestic scenes, with the interiors and gardens of their country estate, Le Clos, providing Edenic settings for his works like “Boy Eating Cherries.”

Vuillard, with a more working-class background than the other four artists, continued to live with his mother and sister well into adulthood, and his paintings frequently reflect not only the dressmaking business that they conducted out of their shared home, but also the tensions of multiple adults, with complicated family hierarchies, living and working in the same small space. Vallotton, for his part, was nakedly cynical about family life. Embittered by an unhappy marriage and torn between his rebel heart and a desire for the comforts of bourgeois life, he produced paintings like “The Lie,” whose saturated colors and jarring, interlocking shapes rather unsubtly suggest the evil of deception and infidelity.

As the above suggests, the women in these artists’ lives had an outsized influence on their work. There are several complexities to unpack here. One is that, while women are the constant subject of the Nabis’ work, the group included no women artists whatsoever in its ranks. Another is that their choice of subject matter strongly connects to the work of the earlier Impressionist painters Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, but they had painted such scenes at least in part out of necessity, since as women they were not allowed the same social freedoms as men like the Nabis enjoyed. Brown does not believe that the Nabis felt themselves particularly influenced by Cassatt’s and Morisot’s domestic scenes; she argues that they approached the subject instead through growing interests in symbolism, interiority and psychology evident in, for instance, the paintings of Gauguin and the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé. This is no doubt true, and yet it is nearly impossible to look at “Washing the Baby” or “Boy Eating Cherries” and not see, in their attention to the details of fabrics, their close-cropped compositions and their graphic debt to Japanese woodblock prints, a reflection of Cassatt’s work from some 20 years earlier.

“Woman in a Striped Dress” by Édouard Vuillard (French, 1868-1940), 1895. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, collection of Mr and Mrs Paul Mellon. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. ©2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

The Nabis’ paintings derive from the largely invisible labor of women in many ways, a point that guest essayist Francesca Berry makes in the catalog. What might read to modern viewers as tranquil, aesthetically pleasing, largely passive pursuits on the part of the pictured women might in fact be the legitimately difficult work of childcare, home education or, in the case of Vuillard’s family, handwork for pay. Further, modeling was itself work that would have been compensated in non-familial contexts. Berry also points out that artmaking was a family business for all the artists, just as much as dressmaking was for Vuillard’s family. Unsung and unrecognized, the women in these artists’ families participated in that production – stitching tapestries, developing photographs – beyond just inhabiting and adorning the domestic spaces their male family members painted.

The constant presence of textiles and patterns in the Belle Époque emerges as a primary concern for all the artists. Vallotton’s “The Red Room” is punctuated by a tile fireplace mosaic and an Oriental rug that share similar windowpane designs. The scrolled tablecloth in Denis’ “Our Souls, in Languorous Gestures” (which appears to show an actual, non-languorous music lesson) has an echo in the highly decorated lamp shade only partially visible in the upper left. But for Vuillard, pattern was more than just an aesthetic concern – it was a constant presence in his life as well as a primary source of sustenance for his family. Evident in his paintings are scraps of the fabrics that would have filled what Brown calls the “hothouse environment of home industry” that was his apartment, where his painting studio shared space with his mother and sister’s dressmaking business. We see such patterned fabrics in “Woman in a Striped Dress” not only in the titular frock but also in the two other competing dresses, as well as in the similarly juxtaposed textiles of “Child Wearing a Red Scarf.” Brown points out that this “close stitching together” of different patterns and textures has often caused Vuillard’s work to be compared to tapestries.

Bonnard takes the use of fabric patterns even further, flattening them so that they do not follow the curves of his models’ bodies but seem to exist on their own pictorial plane, as in “Family Scene” or “Women with a Dog.” Titles like “The Checkered Blouse,” applied to a portrait of the artist’s sister, seem to suggest that the pattern is, in some vital sense, the true subject of the work, although in the latter two paintings the winsomely drawn dog and cat offer some competition (the Nabis loved their pets, a theme that gets some acreage in both the exhibition and the catalog, with an essay by Kathleen Kete). Brown sees the strong influence here of Japanese printmaking, not just the higher-brow ukiyo-e prints that also inspired, for instance, Cassatt, but also the more colorful, mass-market crépons that Bonnard collected and hung on the walls of his studio for inspiration (he was known among his colleagues as “le Nabi très japonard” for that reason). “They’re kind of both interested in these flat planes of color or pattern juxtaposed with one another, without a lot of perspective or attempts to create the illusion of space,” Brown says.

“Washing the Baby” by Maurice Denis (French, 1870-1943), 1899. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Image ©Catalogue raisonné Maurice Denis. ©2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Brown sees, both in these precedents and in the work of Bonnard and the other Nabis, a reiteration of that central idea behind the Nabis’ credo: that art should not just describe but should also get at deeper meanings; that it should not just show what something looks like but on some level how it makes the artist feel, which may, in turn, provoke a response in the viewer. “They’re so interested in interiority,” Brown says, “and by that I don’t mean literal domestic interiors but I mean interior life, a life of the mind and the imagination. They want to…provoke thought and imagination and reflection and to show that kind of mystery of human existence and the complexity of the human soul.”

Fair enough – but how to communicate that to the average museumgoer? Brown hopes that some innovative installation techniques will help. The CMA’s soaring temporary exhibition galleries will be brought down to a more intimate scale with wainscoting and other faux-architectural elements, creating an illusion, at least in some of the spaces, of the kinds of domestic interiors in which these works would have been created and displayed. Historic wallpapers will cover accent walls in the galleries dedicated to the themes of Intimate Interiors (with a sub-gallery about Troubled Interiors), Family Life, and Music in the Home. In the latter gallery, actual music will help to set the mood: the CMA commissioned Arseny Gusev, a student at the Cleveland Institute of Music, to create recordings of a suite of piano music, “Little Familiar Scenes,” written by Bonnard’s brother-in-law, Claude Terrasse, and for which the artist illustrated the sheet music. The music is long out of print and no other recordings exist – so Gusev played right from a carefully made copy of the original illustrated score.

In the end, the exhibition seeks to achieve or at least reflect what the Nabis themselves sought to do in their artwork: to “suggest, not tell,” as Brown puts it; to “make a new kind of art that is rich in meaning and rich in suggestion.” For these artists, as different as they are, the home, and everything it reflected and contained and meant to them, was the foundation of that exploration and approach. “There is a reason they stayed so close to home,” Brown says. “Life so close at hand offered such a rich array of suggestive subjects.”

The Cleveland Museum of Art is at 11150 East Blvd. For more information, www.clevelandart.org or 216-421-7350.