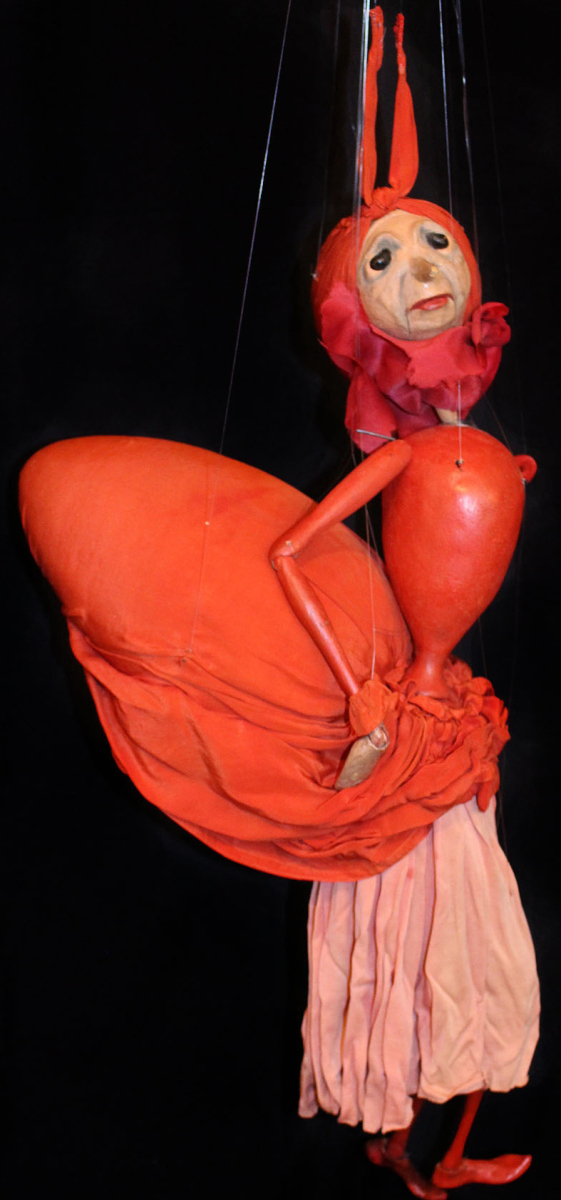

Rose from What the Moon Saw, Sarah Frechette, 2014. Mixed media. Courtesy Sarah Frechette. —Jessie Forand photo

By Kristin Nord

SHELBURNE, VT – They seem to be everywhere. They are in top-grossing films and commercials, on television and on Broadway. They have prominent roles in protest marches and in religious festivals. They set the tone of grandeur and spectacle at the opening ceremonies for the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea. They are the giant inflatables that steal the show in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

These inert objects come alive for us as finger, hand or rod puppets, or as shadow theater. They have the capacity to be irascible, irreverent and violent – but also politically savvy, poetic and profound. And sometimes, as Finn Campman, a Vermont puppeteer who has worked and toured internationally with the Sandglass Theater, notes, we can be simultaneously captivated and unnerved by them.

“Having been a puppeteer for many years I’ve found some people are naturally comfortable and drawn to having experiences with puppets…while others recoil from it. I think it has to do with being forced to believe in something that isn’t alive. You are actively participating in a manipulation. There is a purity to it, from the ways that often-mundane materials take on metaphoric qualities,” he explains.

On view at the Shelburne Museum through June 3, “Puppets: World on a String” features a gallery full of these objects. The show organized by Carolyn Bauer offers a broad-brushed exploration of this theater art, drawing upon works from the permanent collection as well as many objects on loan.

The writer Kenneth Gross has suggested, “There is something in the puppet – in its paradoxes of scale and weight – that ties its dramatic life more to the shapes of dreams, the poetry of the unconscious, than to any realistic drama of human life.”

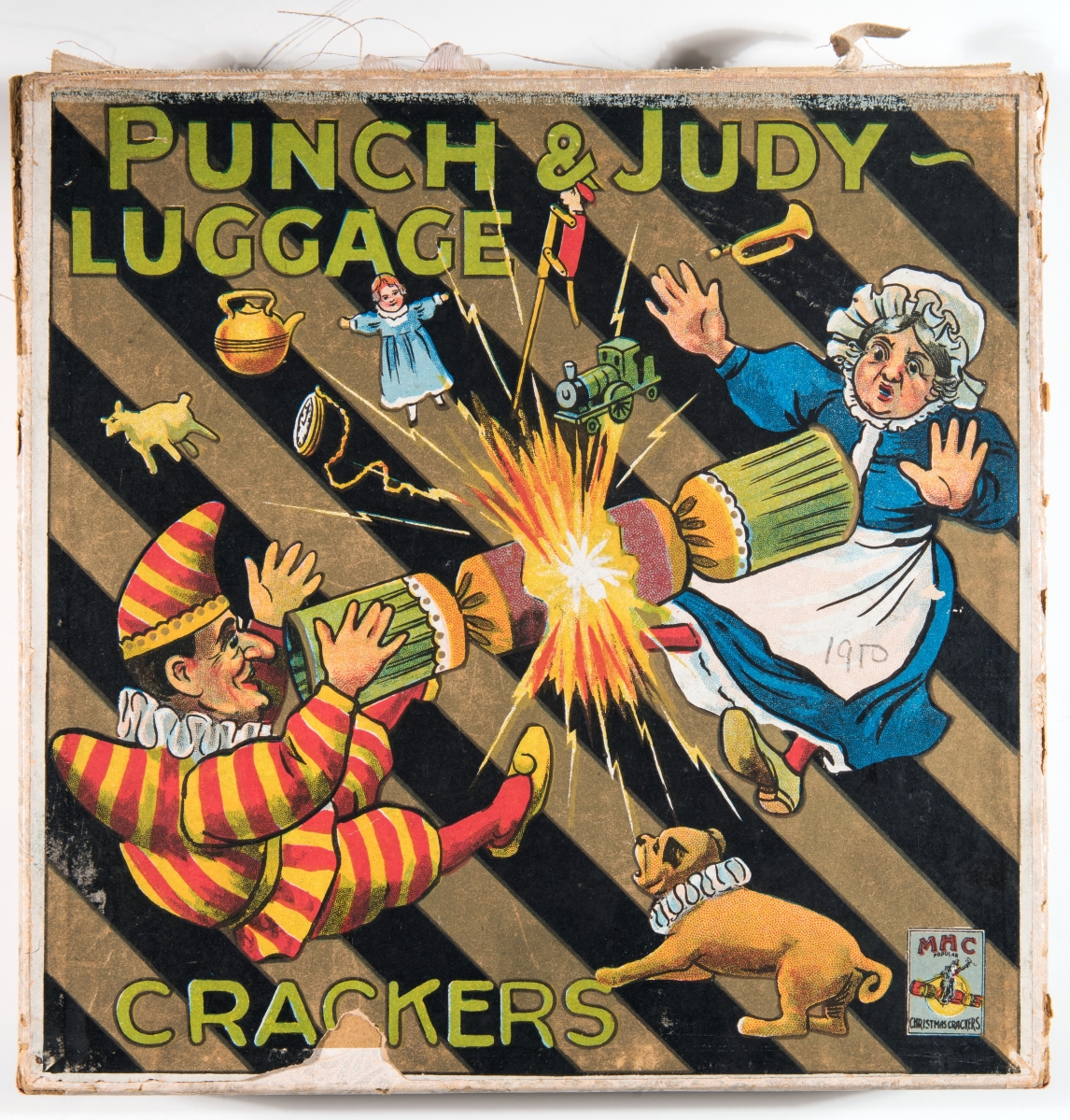

Perhaps because of this, when we encounter a Nineteenth Century giant-sized Punch, once employed as a prop at a cigar shop, we accept this classic anti-hero on his own terms. Punch exists under many names and guises and in many countries, with his evil temper and his penchant for violence, intact. He thumbs his nose at authorities and whacks his wife, Judy, with his slapstick. Yet when he takes on the devil, we cheer for him. As the consummate bad boy he is very good at hawking tobacco, or British holiday crackers, for that matter.

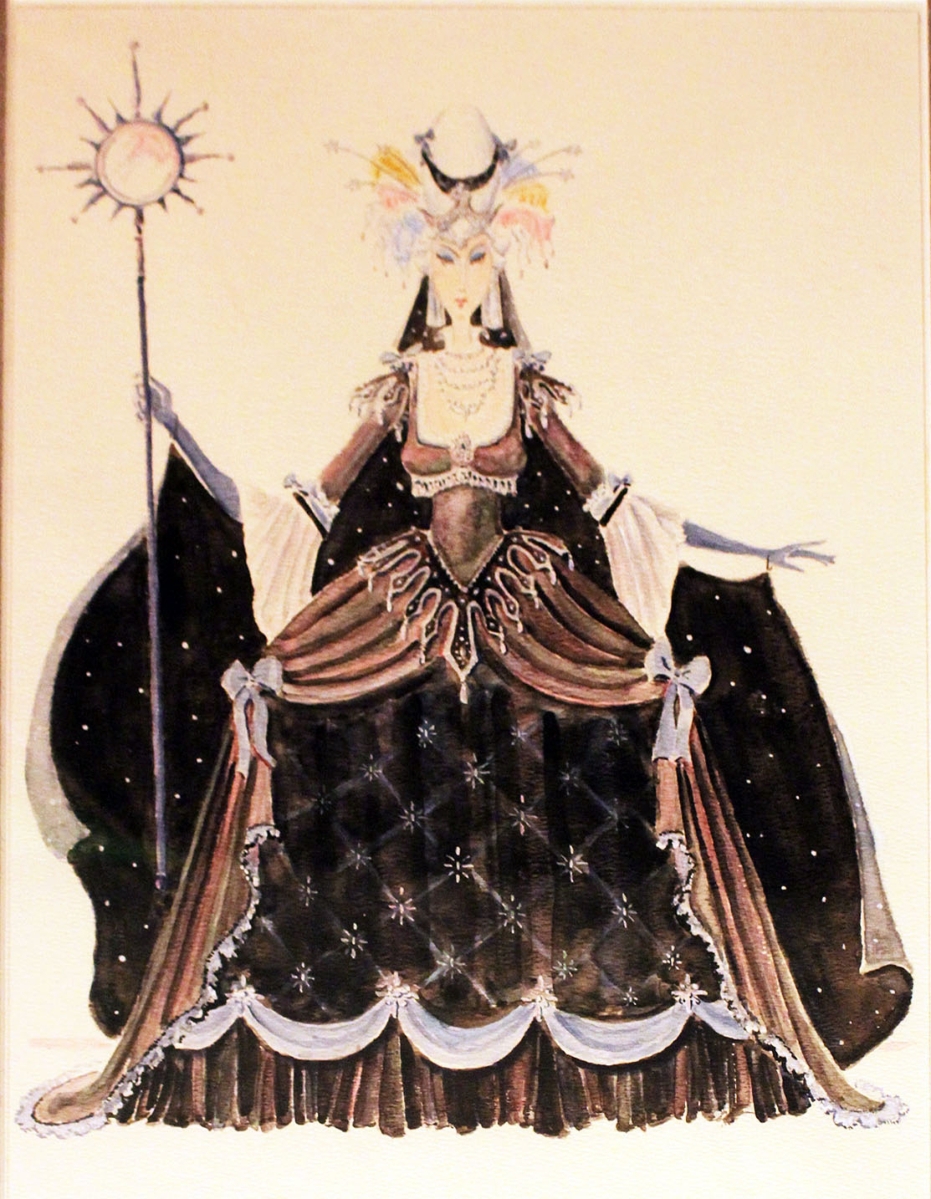

Diametrically opposed in tone, scale and style are a pair of the late Frank Ballard’s masterfully carved and appointed marionettes. These two, the Queen of the Night and Prince Tomino, were created for a production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s The Magic Flute. Ballard’s preparatory sketch suggests his evil Queen will have no trouble scaling the high notes in her death-defying “vengeance aria.”

Diametrically opposed in tone, scale and style are a pair of the late Frank Ballard’s masterfully carved and appointed marionettes. These two, the Queen of the Night and Prince Tomino, were created for a production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s The Magic Flute. Ballard’s preparatory sketch suggests his evil Queen will have no trouble scaling the high notes in her death-defying “vengeance aria.”

If Ballard set the bar for marionette craftsmanship, other Twentieth Century puppeteers are building upon this and other traditions. Sarah Frechette is one of them, having earned a degree from the University of Connecticut’s prestigious puppetry arts program created in his name. While her first professional production adapted classic fairy tales, she is increasingly turning to Vermont’s rural history and its local characters for inspiration. The egg-headed puppet carved during an apprenticeship with Albrecht Roser, in Buoch, Germany, pays homage to her late grandfather, who worked as the supervisor of the poultry building at the Champlain Valley Exposition. She plans to build her next production around Wally, as the object has been dubbed.

The Sandglass Theater Company, based in Putney, Vt., has never been averse to taking on political subjects, but in its “The Ballad of the Ice Shanty” it conjures an ice village that typically comes to life on a frozen lake. Sandglass’s fishermen, crafted as rod puppets and dressed in rough wool, feel authentic. They speak to us as archetypes, as Vermont’s everyday people.

Known for its progressive politics and innovative education, Vermont has served as a fitting base for several longstanding puppetry companies with international reputations. The Sandglass Theater is one. The Bread and Puppet Theater, with its more than 50 years in the Northeast Kingdom, is another. Theater founder Peter Schumann is very much in evidence in the manifesto that accompanies the bold relief created for this exhibition.

“We here wish to dispense of the incompetent ruling class by throwing them from the toes up, and immediately implementing the thousand alternatives to the destructive habitats of capitalism,” Bread and Puppet Theater proclaims. “Politics must abandon their traditional war and weapons preoccupations and make the severe health issues of our one and only Mother Earth and her Earthlings their primary concern.”

Schumann, who survived aerial bombing as a child during World War II and who fled what was then-Hungary with a suitcase full of wooden puppet frames, has continued to use Bread and Puppet as his bully pulpit, mixing spectacle and challenging content alongside his famous homemade bread and garlic-aioli parsley.

Queen of the Night on a Cloud from The Magic Flute, Frank Ballard, 1986. Wood, neoprene and fabric. Courtesy Ballard Institute and Museum, University of Connecticut.

Since the 1960s, when Bread and Puppet first took to the streets of New York in opposition to the Vietnam War, the company’s message has been consistent. “Its radicality,” according to Dr John Bell, the director of the Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry at the University of Connecticut, can be found in “not simply its willingness to include political questions and political action in its art, but its belief that the direct engagement of Americans with papier-mâché, wood, cloth and cardboard puppets offers a profoundly effective – and democratic – means of explaining to ourselves and to others what our life in the Twenty-First Century world means and could mean.”

By the 1950s, advances in television opened doors for puppetry, though it was suddenly seen as an art form for children. Generations of children grew up with a succession of puppets who would help them with their letters and numbers even as they acquired social skills. Howdy Doody, the cowboy marionette created by Margo and Rufus Rose, became so famous that pop artist Andy Warhol took Polaroid head shots to cement the object’s status. Jim Henson and his puppeteer colleagues perfected methods for working within the television frame, eliminating the need for a traditional booth stage. His Muppets were instantly liberated and able to interact seamlessly with people. A decade later, filmmakers saw possibilities as well.

Yoda became perhaps the most famous puppet of the Twentieth Century, though even today few people know that master puppeteer Frank Oz and three assistant puppeteers were at the helm. Yoda was primarily a Bunraku puppet, but additional puppeteers were brought on board to manipulate Yoda’s eyes and ears via remote cables. After the Star Wars franchise’s tremendous success, other acclaimed and top-grossing films that combined actors and high-tech puppetry became part of the norm.

Meanwhile, new media artists, including the renowned Tony Oursler, were experimenting with digital automata. Oursler is famous for his videos of faces and synced audio recordings on inanimate three-dimensional objects. He does not disappoint with his work Plaid Doll, in which an unassuming rod puppet is assaulted by auditory overload in an unsettling barrage of signs, groans and blood curling screams. Nonsense words and suggestive erotic content are disorienting, though to the viewer’s request for order, Oursler’s response is oblique. “Sometimes I feel it’s my job to capture a kind of poetry, and once it’s recorded, it has a life of its own,” he has said.

Similarly, Laura Heit’s Two Ways Down appears at first to be serving up a sugar spun concoction of paper, cutouts and hand-drawn animations interacting with cut-glass panels as projected light casts layered shadows upon a wall. But this is hardly the magic lantern that captivated children in Ingmar Bergman’s film Fanny and Alexander, nor does it display the ebullience of Calder’s circus. Upon closer inspection, Heit’s world is rife with destruction and chaos.

As to why shadow theater’s dual nature (object and shadow of object) seems to inspire existential reflection, Bell wonders if it is a form of puppetry through which one grasps the ambiguity of our times. “In our own high-tech shadow theater, there is both a mystical trust in technology’s power to create a better future, and a deep fear that the same technology might well be responsible for creating just the opposite,” he says.

For viewers up for a road trip, Bell has curated an exhibition that celebrates the puppet revival that developed across the United States in the early 1920s and 1930s. “American Puppet Modernism: The Early Twentieth Century,” at the University of Connecticut’s Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry through July 1, takes a further look at the European avant-garde, Asian, African and Latin American influences that affected this art form, and at the vibrant little theater movement that sprouted in many American cities. At the same time, innovators remained open to the possibilities of new technologies.

Many puppeteers, artists and writers found puppetry to be an ideal medium for representing modern life. Ballard, Tony Sarg, the Roses, Bill Baird and Alexander Calder are among the artists featured. Yale Puppeteers and the Modicot Puppet Theatre are among the meteoric companies that had an impact in their day. The show also looks at the importance of the WPA Federal Theater Project, which kept hundreds of puppeteers working during the Great Depression.

“Our ability to understand the powers of such materials in performance, in the context of US culture and global cultures, will be helpful to us for the rest of this century,” Bell predicts.

The Shelburne Museum is at 6000 Shelburne Road. For information, 802-985-3346 or www.shelburnemuseum.org. Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry is at 1 Royce Circle in Mansfield, Conn. For information, 860-486-8580 or www.bimp.uconn.edu.

Journalist Kristin Nord divides her time between Connecticut and Nova Scotia.