The Word in the Wilderness: Popular Piety and the Manuscript Arts in Early Pennsylvania, is a recently published book by Alexander Ames that examines Pennsylvania German manuscripts from a fresh perspective. We caught up with Ames, formerly a Winterthur graduate student and now the collections engagement manager at The Rosenbach, a historic house museum and special collections library in Philadelphia, for his insights on what inspired his research and what he hopes his book will bring to this popular category for collectors of American decorative arts.

Can you describe how this project evolved?

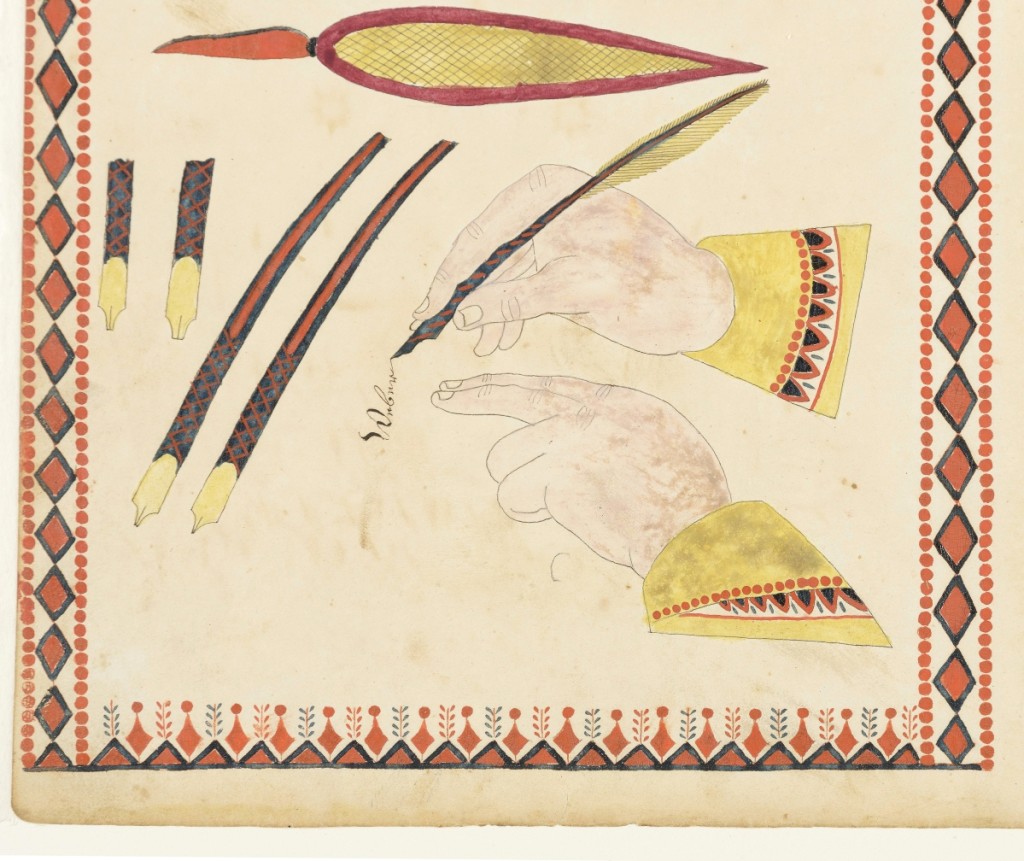

It began in my very first course at Winterthur; we were expected to choose an object from the museum’s collection to study using the methodology of material culture. I had never had any experience with fraktur and I picked a single leaf that had been in a book of penmanship by Johannes Bard. That research paper presaged the direction my research took; to focus on placing Pennsylvania German calligraphy in broad historical context. It eventually evolved into my master’s thesis and, eight years later, this book.

What was it about fraktur that really resonated with you?

That’s a question I’ve thought a lot about.

So much hasn’t been written. The thing that grabbed me – an intuition – was that there was something fundamental about this cache of source material that hadn’t been said before. Pennsylvania German manuscripts have been extensively studied and well known in collector’s circles, but the research didn’t address what the documents really said and meant, specifically in the context of American religious history and to the people who made and used them.

Was that the goal of your research?

The most important goal of my project has been an attempt to place the Pennsylvania manuscript tradition within the trans-Atlantic manuscript context. In the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Centuries, the production of manuscripts remained a very viable form of text production and dissemination. Very often, we think of that time period as an age of print, but handwriting remained important. A critical aspect of my research has been to show how Pennsylvania German manuscripts figure in a much larger story of manuscript culture and history.

These manuscript pages are written in German. Do you think language has been a barrier to understanding them?

To some extent, yes. Mainstream scholarship has not paid more attention to these because they are in German but perhaps more importantly because they are a connection to cultures and traditions that may be hard to understand if you don’t understand that culture. One thing I noticed fairly quickly after I’d studied them is that the texts that are quoted are frequently very familiar texts. They’re often cobbled together from a variety of sources, including hymns, bible verses and scripture, so if you can decode a few words, you can figure out what is being said. We are fortunate that many of the sources for the text are traceable; you can do key word searches. But we also need to look at the scribes – the authors of these documents – who were copying well-trod texts but with the intent to present artwork and religious morals to a new audience.

How do you start to understand how these were used and experienced?

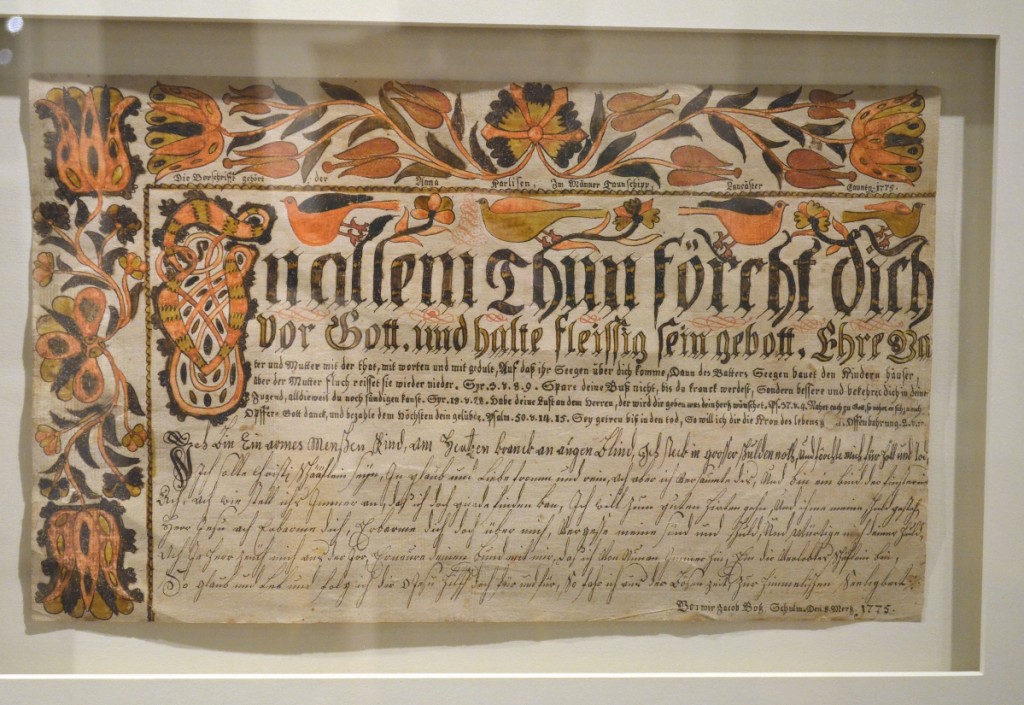

The documents themselves can tell you a lot about usership and readership; in a way it is an archaeological enterprise. You look at the documents for physical signs of how they were used. For example, with penmanship samples, many survive today with crease marks in the center of the document because they would have been folded and stored in books, tucked safely away from light.

One of my favorite research memories happened at the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, where I was working with three Mennonite family bibles owned by interconnected families that had been donated with the manuscript contents of the volumes still present. You could see how these bibles became repositories for family documents over the years. It became evident not only that it was important to the family to preserve the manuscripts but that they were viewed as part of a broader religious experience.

That’s an interesting observation. Can you elaborate?

At the Mennonite Heritage Center, I studied a penmanship sample for a young person of Mennonite background. The penmanship sample itself was quite ornate and colorful. It came equipped with a simple sheet of paper inscribed with information implying that it was a cover for the penmanship sample, suggesting that the scribe viewed the sample as an important work of art that needed to be protected.

We think of the Mennonites and other similar religious groups in this period as avoiding excess and ornamentation…why do their religious texts become heavily ornamented?

It’s an important question that aligns with the Protestant Reformation. We shouldn’t be surprised that in a robust German Protestant community, the text by which religious values are communicated become the visual artwork itself. The idea is that the word of God in the form of holy scripture – as well as other holy texts like beloved hymns – is an object of veneration, that its not just text for the sake of communication.

In our secular age, we have to work to put ourselves in the mindset of a religious tradition outside of our own. It was important for me to imagine what these documents might have meant in this past world. I felt it was important to place these artifacts within the context in which they emerged, as much as one could.

What is your own personal religious background? Did it influence your research?

I grew up in a German Lutheran household in Minnesota, so the culture feels very second-nature to me. I feel a certain familiarity when I am in Pennsylvania German territory, but that was not the reason I focused on this material. I thought that to understand why manuscript-making survived among the Pennsylvania Germans as an important art form I would need a thorough grasp of the theological underpinnings. It was a daunting prospect to have to understand that world, but it was fascinating. I engaged with the rich scholarly tradition on Pietism and Anabaptism as they flowered in the early modern period but also studied the devotional literature that had been influential both in Europe and Pennsylvania.

The manuscript page that launched Ames’ research. Johannes Bard (1797-1861), fraktur writing sample, Union Township, Adams County, Pennsylvania, 1819-1821. 7¾ inches high by 8½ inches wide. 2011.0028.022. Gift of Nick and Jo Wilson. Courtesy of the Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Del.

What did you learn from that?

One of the most important things I learned, primarily through identifying key works of popular piety and well-known devotional books in Pennsylvania, was that reading was a fundamental devotional activity that one had to do with an eye towards spiritual growth.

I hope readers of my book will find it useful to create a foundation to understanding the reality of manuscript production in the United States and Europe, and how Pennsylvania German religious practice connected to that larger context.

What reception have you – an outsider to these communities – received?

I was incredibly thrilled from the very beginning with how welcoming all of the collecting repositories were to me – a junior scholar, a doe-eyed grad student – from day one. Everyone was incredibly welcoming of my presence, my questions. The various institutions in the mid-Atlantic have helped guide my thinking, and everyone is very eager to engage in discussion as to how people can understand these sources. There has not been any concern that I could be misinterpreting the manuscripts because I have striven to adhere to the letter of the word, in terms of what the documents say, how they are studied, and placing them within a religious historical context.

What were some of the surprises you stumbled on in the course of your research?

There are two memories that stand out. One of my favorite recollections of the whole process, one which occurred relatively early on, in January 2013, was a long chat I had with the late Don Yoder, who was regarded as the dean of Pennsylvania German Studies and whose own research had a robust historical perspective. I really wanted to learn from his decades of wisdom about good research directions and was really interested in how these Pennsylvania German manuscripts fit into the wider world of manuscripts. What he told me was very specific: he had always been interested in the fact that so many of the scribes had a special affinity for the Apocryphal Book of Sirach, which is known as one of the Wisdom books and is part of the Old Testament. He told me he thought it would be interesting to know why that book was so important. By then, I had noticed that on the documents I had studied, quotes from the Book of Sirach frequently appeared; after that I always had my eye out for more.

And the other story?

I am so grateful for that direction from Professor Yoder because a very powerful moment for me, which came later, was the realization that books dealing with the wisdom tradition – both canonical and apocryphal – were exploring big questions such as to how to know God, how to know Wisdom and how to achieve Salvation. The manuscripts are filled with verses from those books, and that put me on a path toward thinking of these documents in a much longer and broader historical context. I realized the extent to which the making of manuscripts and the importance of penmanship and calligraphy stretched far beyond Pennsylvania. We tend to think of them as being very particular to the Pennsylvania Germans but that kind of instruction was taking place around the world at the time.

In my book, I illustrate an example of Eighteenth Century penmanship; it looks very different but shows that beautiful penmanship was important in New Spain.

Jacob Botz, Vorschrift (penmanship sample) for Anna Carli/Charles, Manor Township, Lancaster County, March 8, 1775, 7- inches high by 13- inches wide. David G. Charles Collection, Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, Lancaster, Penn.

The title of your book is ‘Word in the Wilderness;’ where does that come from?

The title has several meanings, perhaps the most important being the inspiration I found in the great intellectual historian Perry Miller, who is most closely associated with Harvard and thinking about the role of Puritanism in New England in the American historical imagination. “Errand into the wilderness” is a quote from a Puritan source that Miller used as the title of an essay he wrote; actually, the essay began life as an address he gave for an exhibition on early Puritan texts. Just as Miller and other intellectual historians have looked to the Puritans to understand the origins of the United States, I have put forward the illuminated manuscripts of the Pennsylvania Germans as having something important to say about America’s early cultural foundations.

What do you hope this book does for the field of Pennsylvania German decorative arts?

My research would have been impossible without the work of so many scholars and collectors. I am very aware that I am standing on the shoulders of giants; I am so grateful. My hope is that this book provides another perspective to any and all who are interested in the material. Nothing in my arguments contradicts the decorative importance of these illuminated manuscripts; I am attempting to add another element.

The wider intellectual research enhances these works. I hope my book encourages those who are enthusiastic about these manuscripts not just to showcase them but to interpret them as artifacts of past cultures. I hope to encourage further exploration of these sources. I’d like to think my book is a natural next step in interpreting the material.

-Madelia Hickman Ring