In 2024, the world celebrates the sesquicentennial of the first independent exhibition of the French Impressionists, marking 150 years since the “Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers, etc.” opened in Paris on April 15, 1874. “Impressionism 150: From Paris to Connecticut & Beyond,” the Florence Griswold Museum’s new exhibition, on view through September 8, locates the role of Connecticut artists and settings in this narrative. Antiques and The Arts Weekly sat down with Amy Kurtz Lansing, curator at the museum, to get the inside scoop on all things “Impressionism 150.”

Was the 150th anniversary of Impressionism the sole rationale behind the exhibition or was there more behind its conception and execution?

Part of the museum’s core story or identity is that of the home of American Impressionism, based on the style practiced by artists who visited Florence Griswold’s Old Lyme boardinghouse after Impressionist Childe Hassam first painted locally in 1903. The anniversary was a natural milestone for us to commemorate, and at the same time, creating an exhibition about Impressionism’s beginnings and evolution allowed us to draw upon that core narrative in a more intentional way. Artists came to Old Lyme to paint Impressionist pictures, but we had the chance to ask why Impressionism appealed to them and what was behind American artists’ commitment to Impressionist techniques. We can see that Impressionism has enduring appeal and this show allows us to consider why. The exhibition topic also permits us to celebrate the permanent collection, which includes wonderful pieces by Childe Hassam, the largest public holdings of work by Willard Metcalf and spectacular new gifts to the collection, like Lawton Parker’s “La Paresse.” An exhibition like this enables us to share both audience favorites and recent acquisitions.

“The Ledges, October in Old Lyme, Connecticut” by Childe Hassam (1859-1935), 1907, oil on canvas, 18 by 18 inches. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. 2002.1.66.

To give readers and potential exhibition visitors some essential background information, are there significant differences between French Impressionism and American Impressionism?

Rather than a single definition of Impressionism, I suggest we instead think in terms of “Impressionisms,” since a look back at the first French Impressionist exhibition in 1874 shows us that there was not one single approach practiced by the 31 artists in that show. But in broad terms, a major difference between the work of the French Impressionists and the American Impressionists is the persistence of form and drawing in American artists’ works. American artists went to France in the late Nineteenth Century to learn the academic techniques French Impressionists were busily rejecting in favor of loose brushwork and an attention to color and lighting that would capture the “instantaneous” feeling of looking at the world around you. American artists, with Lawton Parker as one example, continued in works like “La Paresse” to incorporate big, carefully modeled human figures. Robert Vonnoh paired reds and blues to create a high-key radiance and reflections in “Beside the River (Grez),” but did that over a structure of solidly drawn architecture. Artists like John Henry Twachtman, whose “Gloucester” is in the exhibition, embraced a level of abstraction akin to Monet’s, but even circa 1900 — decades after Impressionism’s debut — American critics expressed discomfort with the flatness and lack of perceived finish of Twachtman’s canvas.

American artists came to Impressionism later than their French contemporaries. The first exhibition of French Impressionist paintings in New York didn’t take place until more than a decade after the Paris debut. Because many American painters first embraced Impressionism while visiting rural French artist colonies, they tended to focus less on the urban subjects that drew the eye of their French counterparts registering Paris’ modernity, and more on rural landscape and quaint historic villages. I’d also say that there is a strong regional accent in American Impressionism as artists immersed themselves in the local landscapes of places like Old Lyme, Cos Cob, Gloucester or Monhegan. Impressionism spread across the United States as artists moved between or established new artist colonies.

Did Old Lyme Impressionists have their own style? What does this look like?

Flickering brushwork — evident in paintings like Childe Hassam’s “The Ledges, October in Old Lyme, Connecticut” and Willard Metcalf’s “Dogwood Blossoms,” influenced a number of Impressionists associated with Old Lyme. But more often, Old Lyme Impressionist works share subject matter rather than style. In the colony’s heyday, critics noted the frequent depictions of historic village architecture like the town’s First Congregational Church, seen in Everett Warner’s “The Village Church;” of mountain laurel flowers like those in Matilda Browne’s “Blossoming Flowers on River’s Edge;” and of colorful gardens like artist Will Howe Foote’s own garden in “Summer.”

“Spring Study à Grez” by Willard Metcalf (1858-1925), 1885, oil on canvas, 24 by 20 inches. Florence Griswold Museum, From the Family of Anne Earle (Babcock) Smullen, gift by Eleanor Tennyson Smullen. 2023.6.

Were there any surprises that came to light as you were preparing for this exhibition?

As we prepared this show, the museum was given a Willard Metcalf painting, “Spring Study à Grez,” that had not been seen in public for a century. It was a wonderful surprise to be contacted by the donor about the painting (still in its original frame), which the artist gave as a gift to the family of anthropologist Frank Hamilton Cushing. While we have a substantial collection of Metcalf’s work, nothing represented his time visiting the artist colony at Grez. The donation of “Spring Study à Grez” gave us the chance to compare and contrast it in the exhibition with a later painting Metcalf did in Giverny, and together the pictures show how he experimented with Impressionist brushwork and color. The museum is lucky enough to own Metcalf’s cabinet of natural history specimens as well, and the exhibition includes the cabinet with drawers open to show some of the bird eggs the artist collected in both Grez and Giverny.

In the press release for “Impressionism 150,” it says that the exhibition “closes with a group of paintings that focus on race, gender and the environment to demonstrate the vast potential for understanding the picturesque works with fresh eyes.” Why do you believe it’s so important for us to view Impressionist works with these viewpoints in mind?

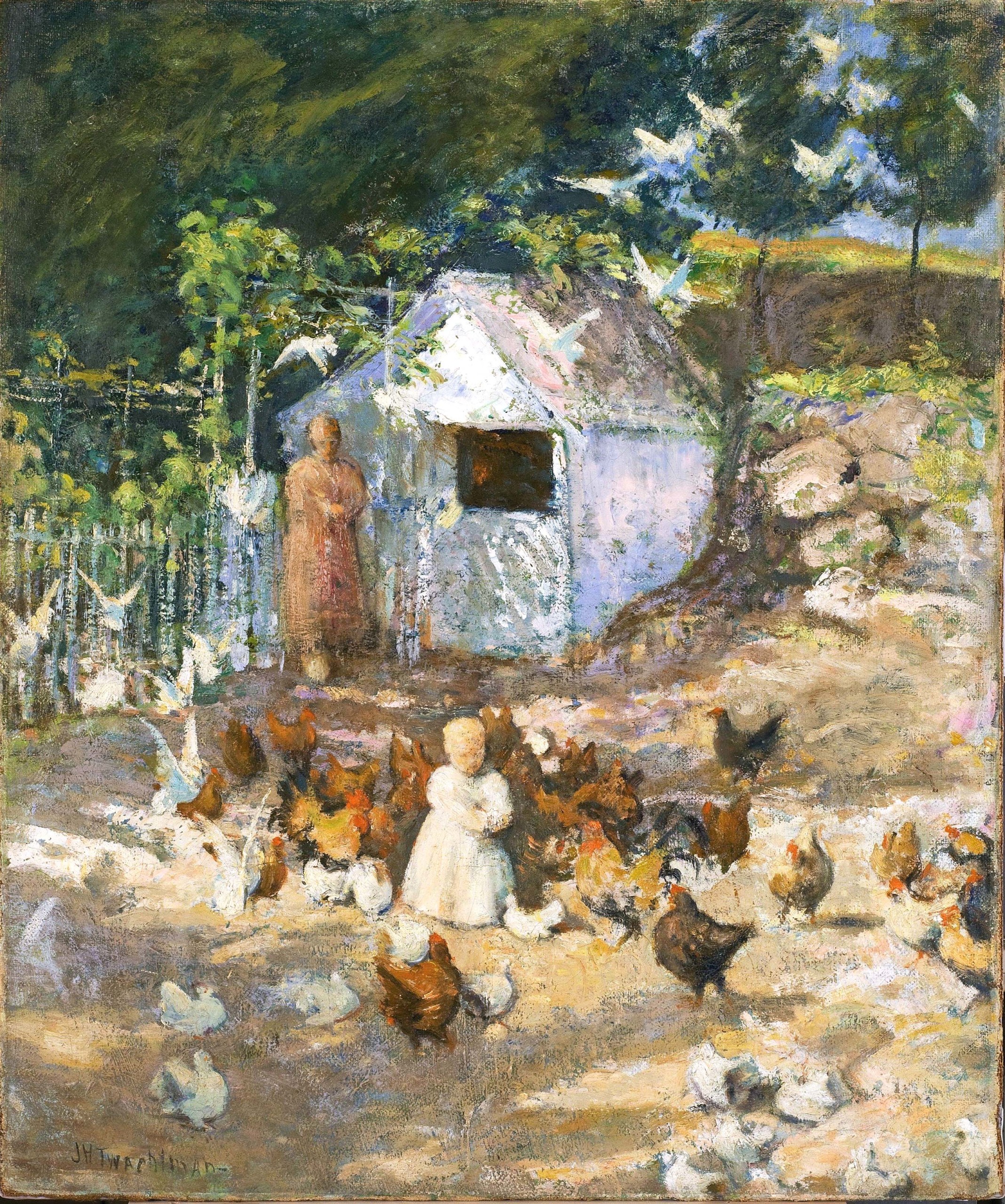

The first generation of Impressionists developed an artform that responded to the contemporary world in which they lived. It’s important to continue examining historical works from a wide array of perspectives so that we can fully understand not only the cultural moments in which they were created, but our own moment as well. When we consider the longer history of Native Americans and African Americans dwelling upon and being displaced from the land in the Hangroot community of Greenwich depicted in Twachtman’s “Barnyard,” for example, how might it shift our perception of the painting as an image of home and family? Another painting in the exhibition is by Mary Bradish Titcomb, who depicts her fellow women artists sitting on the porch at Boxwood Inn in Old Lyme. Women stayed there because they were not welcome in the clubby male atmosphere at the Griswold House. Titcomb’s gorgeous painting demonstrates the accomplishment of women Impressionists in Old Lyme, despite male artists’ claims that these painters, in their white dresses, were “blots on the landscape.” Titcomb’s signature was at one time folded under and the painting falsely identified as the work of a male Boston School artist, but now her contributions have been revealed — an ongoing project for those whose stories have been excluded from our histories. It’s important to keep the viewpoints of race, gender and the environment in mind because otherwise we are only telling part of the art’s story. We want audiences to feel that they can find historical information about the art that provides context for their own lives and experiences today.

“Barnyard” by John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902), circa 1896–97, oil on canvas, 30¼ by 25-1/8 inches. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. 2002.1.142.

Does the exhibition draw exclusively from works in its collection? If there are loans, which were, in your opinion, critical for the inclusion in this show?

This exhibition draws exclusively from the permanent collection. In fact, we could have done this show over again because the museum is lucky enough to have a depth of Impressionist paintings and works on paper to draw upon.

What was your criteria for including (or excluding) works?

I wanted to include works that would best tell the story of Americans’ slow embrace of Impressionism — pieces that showed how traditionally they were painting in the 1870s, and how that is gradually expanded by their exposure to Paris and to French art colonies. I was often hoping to include works an artist did in Europe and in America, to make that evolution evident. And I wanted to include work by both male and female artists, since their ability to embrace Impressionism’s avant-garde approach differed. I also wanted to reflect the fact that Impressionism is not a monolithic style, so works could be “impressionist” in different ways and to different degrees. And, of course, I was hoping to include our top pieces, many of which are visitor favorites, as well as to debut recent acquisitions, such as one of the first works on paper Childe Hassam made in Old Lyme.

Does the exhibition break new ground in terms of research or scholarship?

Every time you reexamine works in your permanent collection, you find additional information and develop new ideas through your research. I would highlight the added richness we have brought to the understanding of works from our collection as we interpret them as part of the larger history of Impressionism. How radical Impressionism was, but also how strongly traditional academic approaches persisted in both France and America have been important points in our exhibition and in the exhibition “Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment,” at the Musée d’Orsay, traveling to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, this fall.

—Kiersten Busch