Anthony Wood is a preservationist and author based in New York City who has served as a trustee of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Preservation League of New York State, and countless other boards of regional and national preservation organizations. The executive director of the Ittleson Foundation, he works with numerous nonprofit cultural organizations, Antiques and The Arts Weekly had the opportunity to dig deep into Wood’s passion for historic preservation and what he views as the future of a field dedicated to saving the past.

How did you become interested in historic preservation?

I grew up in a family that valued history. My father was a university history professor who wrote history textbooks. As a family, we would drive around looking at old homes and I grew up in two great old houses. I remember being taken as a child to Fort Ticonderoga and Gettysburg. My mother, among many other things, was a civic activist always writing letters to the editor of the local paper. I love history and majored in it at Kenyon College. However, I decided a purely academic path was too passive for me. Historic preservation, with its blend of history and activism – buildings don’t just save themselves – was a perfect fit for my interests and my upbringing!

What led to your interest in the history of the preservation movement?

After earning a master’s in Urban and Regional Planning with an emphasis on historic preservation (I was the student in the transportation planning class who did his paper on how New Orleans stopped a highway that would have destroyed the French Quarter), I came to New York in 1978 with a desire to get involved in historic preservation. Being interested in history, and also thinking it might help my job search, I went in search of a book or article on the history of New York’s preservation movement. I found nothing. So, I started conducting oral histories with key individuals who had long been leaders in the field. I soon learned that the established myth surrounding the origin of preservation in New York City – that preservation had grown out of the ruins of the demolition of Pennsylvania Station – was just that, a myth. Prior preservation efforts had been going on for decades. That set me on my multi-year quest to learn the origins of New York’s landmarks law, which ultimately led to my book, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks.

Why do you feel the history of the preservation movement is so important?

Many people still take it for granted that cherished landmarks and historic neighborhoods just naturally get saved. They don’t realize that such buildings and special places don’t survive by accident but only through the concerted efforts of people like them. That’s why capturing and telling preservation stories is so important. For preservationists, the movement’s history is our intellectual capital. It can inform, instruct and inspire current and future preservationists. Past victories and losses are full of lessons to be learned. For emerging preservationists, it is so empowering for them to know they are part of a long and honorable tradition. Also, there is a prominent New York historian in the city who maintains that preservation goes against the very ethos of the city, because change is what defines New York. Preservation’s history, however, makes it clear that New Yorkers have been trying to manage change – which is what preservation is all about – for almost as long as change has been going on. Preservation, like change, is also part of New York City’s fundamental DNA. Lifting up the preservation movement’s heritage ensures that we don’t forget that part of the city’s story.

What led you to start the New York Preservation Archive Project?

During the years I was researching Preserving New York, I was repeatedly frustrated when I discovered that the papers of key preservation figures had been lost. When they died their papers had ended up in dumpsters. I also longed to hear first person accounts of major preservation events, but those voices had long been silenced. I realized that someday someone would want to write about more recent preservation history, and they would want the resources that hadn’t been available to me. So, the Archive Project was born to go about doing the work to save preservation papers, conduct oral histories, and celebrate episodes and figures from the rich history of preservation.

What challenges have you faced?

Preservationists are so busy saving history that they forget to preserve their own. It is hard to convince them to take the time to document their efforts. People also seem to think they will live forever so they put off making plans for the long-term stewardship of their papers. Organizationally, we face the challenge of raising money to support our efforts. The charitable instinct of many preservationists is to first support their neighborhood preservation organization, and perhaps then a city-wide preservation group, and maybe the Preservation League of New York State – all worthy causes! But it takes a certain type of preservationist to realize the bedrock-level importance of funding the preservation of preservation’s own history. We’ve made real progress helping people realize the importance of supporting our work, but it can still be an uphill battle.

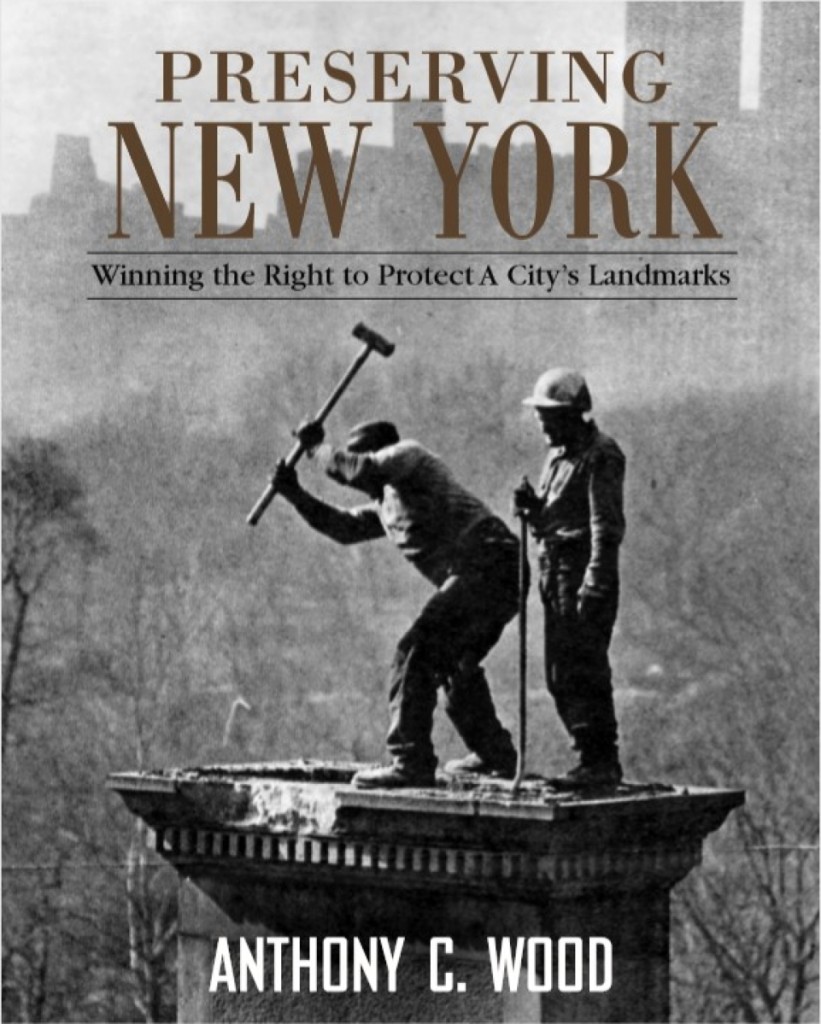

The demolition of the Brokaw Mansions, dramatically depicted on the cover of Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks, is one of the many episodes in the history of preservation in New York City captured through the work of the New York Preservation Archive Project. Photo courtesy of the New York Preservation Archive Project.

What are some of the preservation stories your oral histories have captured?

Our oral history projects have helped capture many important narratives that otherwise would have been lost. Through a series of interviews with the chairs of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, with the lawyers who have defended the landmarks law, and with the advocates who have sought to use the law to save threatened buildings, future historians will have rich primary source material offering multiple perspectives on the last 50 years (and more) of preservation in New York City. I’m delighted we have been able to capture preservation voices ranging from those of neighborhood advocates to policy makers. We’ve recorded oral histories with figures you may have heard of – Kent Barwick and Gene Norman, former Chairs of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. But we’ve also continued to make a concerted effort to ensure we are capturing stories of grassroots preservation in places like Crown Heights, Sandy Ground in Staten Island and the Bronx – stories that may otherwise go unnoticed. Legendary preservationists like Margot Gayle and Henry Hope Reed recount their tales in oral histories as well.

How does one get access to your oral histories?

Our website (www.nypap.org) is the place to go for access to the oral histories we have conducted with preservationists. Transcripts are available and have become a regular resource for researchers, historians, and journalists. The website also includes a preservation database which we regard as the “first stop” for anyone doing preservation research. The entries have basic information on many people and organizations involved in the history of preservation and also direct users to where other materials relating to those subjects can be found.

Tell us about some of the preservation papers you have been able to save?

We’ve saved papers that help tell preservation stories ranging from the campaign to save the Ladies’ Mile (New York’s gilded age shopping district) to battles over historic theatres, to the failed effort to preserve 2 Columbus Circle. We work both with individuals and organizations, from the SoHo Memory Project to the New-York Historical Society. We’ve helped save the papers of activists and architects! From the inimitable activist Jack Taylor to the architect Lee Harris Pomeroy, we manage to ensure that researchers and the public will have unique windows on history. We seek to educate preservationists about the importance of their papers and then we work to find a home for them with a permanent collection institution such as the New-York Historical Society. When people plan ahead, we can be the matchmaker. When they don’t, we are an emergency responder, swooping in to rescue papers before the heirs have to vacate the apartment and the papers go to the dumpster.

How are the archives stored?

Our role is to secure homes for the papers of preservationists and preservation organizations with permanent collecting institutions such as the New-York Historical Society. Once the papers are given to those institutions, they become part of that institutions permanent collection, are stored and processed, and become available to the public through that institution’s regular processes.

How do you get the younger generation interested in preserving the story of preservation?

It has been exciting to see younger preservationists getting involved with the Archive Project. We are particularly lucky to have younger preservationist on our staff and well represented on our board. We have consciously designed programs to attract their interest. Whether it is preservation trivia nights, our annual preservation film festival, with its popular “Preservation, She Wrote” evening which uses episodes of “Murder She Wrote” to explore in a light-hearted way how preservation has been portrayed over time in popular culture, to our Column’s Club, which takes young preservationists on tours offering the backstory behind New York historic sites. All have struck a chord with a younger audience. We have partnered with young preservationists at Preserving East New York to highlight recent preservation history of great interest to contemporary audiences. Recently we held our public program highlighted by the oral histories with preservationists who played a leading role in preserving New York’s LGBT sites at a gay bar. We have also grown a robust, engaged social media presence in the past two years on platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. Clearly, we’re not your great-grandmother’s preservation organization!

What are you working on now?

In researching how New York City got its Landmarks Law, I became fascinated by the largely forgotten and still underappreciated civic champion, Albert Sprague Bard (1866-1963). He was a national expert on aesthetic regulation, bested Robert Moses in the battle to save lower Manhattan and Castle Clinton, was the grandfather of New York City’s landmarks law, and did all that while having a very unconventional and full private life. He is a truly fascinating real New York character and my next project is a book on Bard.

For the Archive Project itself, we are part of a broad civic coalition called “NYC Landmarks 50+,” which is organizing a city-wide celebration of the 55th anniversary of the passage of New York’s Landmarks Law. We are also involved in the “Year of the McAneny,” a celebration of the sesquicentennial of George McAneny, yet another great but underappreciated civic leader responsible for helping shape New York City. I somewhat jokingly describe us as being the Hallmark Cards of historic preservation. Every anniversary provides us another opportunity to help New Yorkers discover and celebrate the city’s long and vibrant history of preservation – one that shows how we’ve fought to preserve the best cultural, historical, and architectural offerings this city has to share with the world.

-Madelia Hickman Ring