With the watch market booming, a new audience of collectors is emerging and showing the telltale signs of interest in the age-old field of horology, but where is that dedicated museum in New York City? It’s now at the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) on West 44th Street, an organization founded 154 years ago that has just launched its very first exhibition from the collection of Bob Frishman, the founder of Bell-Time Clocks, a dealer-of-yore and clock restorer who spends his time lecturing about the history, culture and technology of horology – the science of timekeeping. Frishman, who is also involved with the National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors (NAWCC), steps in as the director of exhibitions at HSNY and plans to launch a series of small-scale shows that aim to get the works running. As the inaugural show ticks on through May 2020, Frishman sat down with Antiques and The Arts Weekly to talk about this budding initiative.

This seems to be the beginnings of a horology museum in New York?

Yes, and the origin story is from probably a year ago. HSNY’s president Nicholas Manousos, who I had gotten to know because I did a presentation there, told me that every week they get a few emails or phone calls from people who are flying in from New York, London, Dubai, and they’d like to come to the museum. And they kind of gulp and say ‘we don’t have one.’ It got them thinking more and more that they needed to try to do something like that so people that come to New York can see some horology and not just dig out some examples at the Met or the Frick. The other trigger for it was Jeanne Schinto’s series of articles about the James Arthur collection formerly at New York University. Arthur was a collector 100 years ago who envisioned a horological museum in New York City and he donated his collection to NYU, where it was displayed at the uptown campus for some years. The story is a long, sad one and eventually the collection got dispersed, NYU got rid of the stuff. I think that also got HSNY thinking they should get started with some sort of horological display in New York City.

Does HSNY have a collection of their own?

No, that was the first thing out of Nick Manousos’ mouth: ‘we’d love to have a museum but we don’t have a collection.’ I immediately shot back, ‘that’s the good news!’ You don’t want to be burdened with a collection – it gets stale, you have to insure it and store it. It’s way better to begin a series of rotating loan exhibits where everything is fresh and you don’t have to get too involved with caring for stuff. Not having a collection was perfect from my point of view.

I understand you’re the new volunteer director of exhibitions. Did it take some coaxing to get you on board?

I certainly jumped at the opportunity. I have other commitments, like with the NAWCC, but I have a lot of trouble saying no to anybody when it comes to this field. It’s a great opportunity for horology. I want to expose the world to what I think are the world’s most interesting objects and artifacts. Whatever I can do to beat that drum I’m going to do it.

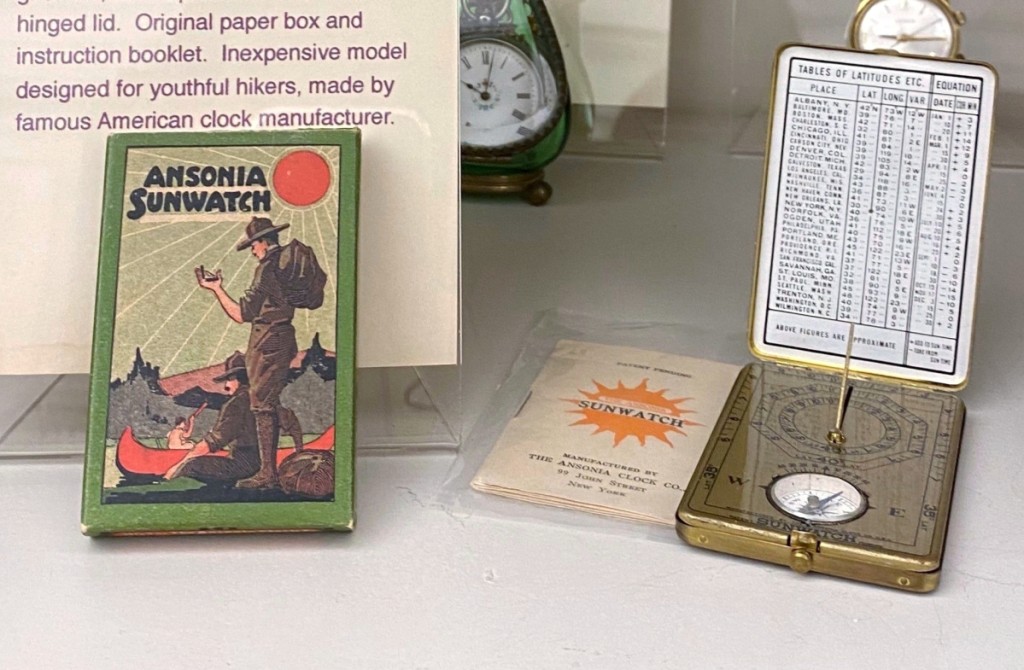

A circa 1920 Sunwatch from the Ansonia Clock Company in Brooklyn, N.Y., displayed here with its original box and booklet, was designed for hikers and outdoorsmen.

To the exhibition – these are things from your personal collection, from outside your shop?

I never had an open shop. Part of my house where I did clock repair and still do, there’s a display area, but mainly I sold at antiques shows. I would pack up 50 clocks and drag them to a show and set up a booth. I tapered off doing that some years ago. Some things I own are for sale, some not for sale, but almost uniformly from the beginning, I bought things I wanted to keep. That made me an effective salesman, because I loved everything I was selling and sold it reluctantly. But the pieces that remain are things that interest me a lot. Probably if someone walked in and asked for a price, I might sell it to them, but they are all of interest and many of them one-of-a-kind or very limited in number.

Describe some of those for me, what are the rarities?

Keep in mind that some of these weren’t made for Rockefeller. Horology is one of these fields where people were always saying ‘I have a better idea, let’s try this.’ My things are oddball, interesting objects, and in some cases they made just one and they ended up in a landfill, or others where they just made a few and they didn’t sell. One of these in the exhibition is a Swing-Wind clock, made by the Novelty Clock Co., circa 1930. It was made in Lawrence, Mass., which is the city next to Andover, where I live. I’ve never seen another one of those, it’s an odd thing where it’s an easel-form desk clock. You rock the easel back and forth and it winds the clock, at least theoretically. It’s possibly a prototype or low-production, a gilt-wood model with a small 30-hour movement by E. Ingraham Co. of Bristol, Conn.

Another is a phonometer by C.H. Graves, Riverside, Conn., that was patented January 29, 1918. It was used to time telephone calls. Everybody would freak out when you talked more than three minutes because you had to mortgage your house to pay for the bill.

Were phone calls very expensive back then?

Hugely, and three minutes was kind of the magic number. So this was a timer, and when that needle hit the red zone, you knew that Ma Bell was coming for you.

I remember the tricks people would employ to avoid phone bills.

I’m 68, and certainly when I was growing up there were all kinds of strategies for calling Grandma when you got home: you’d let it ring three times and then hang up. That was in the 1960s, it wasn’t that long ago that you paid for every phone call. But at the time the phonometer was made, it was serious money if you bumped over the three-minute mark.

Seen here is a night clock by the British United Clock Co., Ltd., Birmingham, England, 1853. A candle would sit behind and light the face through the darkness.

Tell me about some of the others.

I didn’t really know which things other people would find interesting, including the HSNY president. He went right to a Night Clock, produced by the British United Clock Co., Ltd., Birmingham, England, 1853. There were versions of it by Waltham where you would hang it on a gas light fixture in your house, and it would light it up. But this one is English and I haven’t seen another. It’s a 30-hour clock with milk-glass dial illuminated by a candle from the rear. The firm was one of the first in Britain to apply mass-production to clock manufacturing.

Another novelty clock shows a German Shepherd by the Lux company that made millions of novelty clocks in Connecticut. At home we had a series of German Shepherds for 30 years, so that’s what attracted me to that. Maybe more of these exist, but I’ve never seen another. They aren’t the greatest clock movements, so I think that’s part of the issue of what survives and what doesn’t. The cheap things, the novelty things, they stop working in 1931 and then in 1951 the son or grandson asks why they are holding onto it and they throw it out. Quality in antiques is a kind of staying power.

What about pieces with unique uses?

I tried to bring some things that were clockwork, not necessarily timepieces. One of the most prominent ones is a telegraph register. It’s an odd-looking thing with a big wheel on it. I’ve seen the prototypes that Samuel F.B. Morse produced. You not only had to have a little tapping piece that sent out a signal, but you had to have a way to record it, to pull a paper tape at a specific rate through the machine that was punching or inking the dots and dashes. The early Morse example had wooden works. He just needed some kind of clockwork to pull the tape through, so I have an early, interesting one with springs and gears inside, and it’s not telling time or ticking, but it’s pulling paper through.

There’s also a thickness gauge made in Waltham, Mass., by Randall & Stickney. Waltham was kind of a mecca of not only watch making but also watch tool making – all the things to mass-produce watches. They made tools that were used in all kinds of manufacturing applications, which led to America and New England leading the world in industrialization.

Are there any themes or timelines the exhibition explores?

There is a timeline of two themes: accuracy and mass-production. Even 400 years ago, a high level, high-skill watchmaker could hand-make a nice, accurate timepiece. But by the time of Waltham Watch Company in the mid-1800s, they could crank 1,000 of those out of the factory in a day, and they would be accurate and affordable. I have examples of the high-end stuff, too, particularly my Parkinson and Frodsham marine chronometer from the early 1800s, made at a time when they were just starting to make affordable marine timekeepers to keep the ships off the rocks, once they were able to figure out their longitude accurately. But a lot of what’s on display are things that are both good and cheap. So it’s more about affordability, novelty, reliability and accuracy.

Frishman stands with a novelty clock featuring a German Shepherd by the

Lux company. Frishman kept German Shepherds as pets for a number of years

and liked this example for that reason.

What kinds of exhibitions are in the pipeline?

I had hoped, and it is actually happening, that people are starting to come out of the woodwork, I haven’t had to chase them. It’s not like I have ten years lined up, but I wanted to create a template where others can say ‘my collection would look good in that environment, too.’ One thing to keep in mind is that space is still quite limited. Someone who has 50 tall case clocks will not be a candidate, it needs to be small clocks and watches. There’s a good probability that these exhibitions will become more specific. Many collectors are not as general as I am and they collect specific things. The next collection will come out of Connecticut, the gentleman has a number of special watch tools that belonged to Henry Fried, a major watchmaker and watchmaking educator in New York City. HSNY already has his workbench and some of his tools. So during the summer we hope to have Fried’s tools on display. And then in the fall, there’s a gentleman with a very impressive collection of watches, he does a lot of lecturing about them. The principal interest of the HSNY members at this point is the luxury wristwatch market, at least the high-end mechanical wristwatch market. If I keep throwing wood movement clocks at them, they might wonder where the meat is. So it’s important that this gentleman has come forward with a good selection of watches, and we can get plenty of them in a small area. And then I have a couple of people in the pipeline that have interesting, rare, small things. Pretty soon I’ll have the high-class problem of too many options, and then I’ll have to work my way through that – the same way HSNY does with its lecture series, which is really what put it back on the map. Every month they have a world-class speaker, and they’re booked for five years in advance. People are clamoring to talk there and the audience is clamoring to hear them. I hope that’s a template going forward. And there are events around the exhibits, I anticipate every collector who has an exhibition will do a presentation, so it ties into the lecture series.

With the explosion of the watch market, does that lead to an interest in horology?

That’s our dream, we’re hoping that happens. For horology in the collector world, there have been other gateway drugs in the past. For some it was a cheap Connecticut clock found at a yard sale for $5 and they got hooked that way. Or somebody else got their grandfather’s pocket watch and now they have 300. Once those people got into horology, they started going to NAWCC meetings and conventions and they would walk by a table with something different and it expands like that. The goal, and HSNY really believes in this, is to tell a lot of their Rolex collectors about the history: Rolex made pocket watches 100 years ago, and by the way, Hamilton did, too – on and on like that. And by the way, there are these big things called clocks, and you don’t have to hide those in a drawer. When people come to your house, they don’t have to look on your wrist to see something great.

-Greg Smith