Distinguished architectural historian Carl Lounsbury, on staff for many years at Colonial Williamsburg and now teaching at the College of William and Mary, is the impetus behind the new book The Material World of Eyre Hall: Four Centuries of Chesapeake History. It’s a sprawling architectural, sociological and genealogical dig into the history of the Eyre family from the Seventeenth through the Twenty-First Centuries. We sat down with editor Lounsbury to discuss this fascinating volume featuring the work of 22 contributors.

Congratulations on producing such an extensive history so handsomely done. How did you come to take on this project?

After 35 years, I retired as the senior architectural historian from the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation at the end of 2016. I was asked a few months before then by Furlong Baldwin, the owner of Eyre Hall, if I would be interested in working on a book about his family’s colonial house, garden and its many Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Century objects. I think he selected me because of my earlier experience as a contributor and editor of a book published by my colleagues that summarized our many years of research on the early architecture in the region titled The Chesapeake House: Architectural Investigation by Colonial Williamsburg. From that experience, I had the skills he was looking for in coordinating the work of a lot of individuals on a large project that was intended for a scholarly and popular audience. Furlong envisioned a similar book but one focused on a single site. I was well aware of the importance of Eyre Hall to the architectural history of the Eastern Shore of Virginia. From the curators at Colonial Williamsburg, I understood that there was a great collection of household objects dating from the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Century. When I learned about his family’s continuous ownership of the property since the construction of the house in 1759 and that there was a variety of family papers that might shed light on their lives, I was hooked.

How did you assemble your team of specialists?

After many decades at Colonial Williamsburg, I had worked with and knew many individuals who were well versed in historical archaeology, dendrochronology; paint analysis, garden history and material culture, especially the decorative arts. Furlong recommended a few people who already knew the contents and grounds of Eyre Hall intimately. Over the years, he had loaned Colonial Williamsburg a number of his objects for exhibitions and had drawn on the expertise of its conservators when something needed repairing or cleaning. I discovered that his parents had called on the curators at Colonial Williamsburg as early as the 1930s when they were rehabilitating the house after a long period of neglect. So, it was not hard to ask about a half dozen of my former colleagues in collections to write about objects at Eyre Hall that they already knew quite well. For example, Margaret Pritchard had studied the 1817 French panoramic wallpaper in the entrance hall and had illustrated it in the Chesapeake House. Others were also very familiar with Eyre Hall. Mark Letzer, a silver expert and president of the Maryland Center for History and Culture, was a friend of Furlong Baldwin and Louise Hayman and had studied the fabulous collection of silver at Eyre Hall often over many fine dinners. Finally, Will Rieley, the landscape architect and garden historian from Charlottesville, had worked with Baldwin a few years earlier overseeing the stabilization of the ruins of the 1819 greenhouse. These were the in-house experts who quickly signed on to the task. Other contributors included specialists outside of Colonial Williamsburg whom I knew from earlier collaborations, such as Rob Hunter on ceramics, Sumpter Priddy on furniture, Bennie Brown on books and Gary Stanton on sheet music. All of them said yes immediately.

In addition to the specialists, I also spent three years working with undergraduate and graduate students at William and Mary, many of whom were part of the NIAHD program, which had been set up 20 years earlier as a partnership between the college and Colonial Williamsburg to train the next generation of museum professionals through specialized classes in architectural history, historical archaeology and museology, as well internships in regional museums. At Eyre Hall, I had more than two dozen students do basic research on specific objects in the house, such as the collection of musical instruments. One cataloged the family library of more than 800 volumes. A graduate student in anthropology helped excavate and analyze the artifacts at a slave quarter in the domestic work yard. Still others did documentary research by transcribing family papers and account books or scour court records finding evidence pertaining to the family dating from the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century in the Northampton County clerk’s office.

Five of the students ended up contributing to the book by writing short pieces on aspects of the family history ranging from land ownership, horses, to their patronizing of spas. It was a chance to get their first experience of publishing their own research. One of the most exciting discoveries was that whaling was an integral of the Eyre family economy for two centuries. One of the students, Alexandra Rosenberg, wrote a fascinating story of the escape of nearly 20 enslaved individuals in 1832 by whale boat, which they navigated from the inlets of the Eastern Shore to New York City.

In all I had 22 contributors to the book. I was pleased to discover how cooperative and responsive all of them were. They met their deadlines with little or no chivvying. I would also like to acknowledge the help of regional repositories whose librarians and archivists were able to supply images from their collections, especially when they were often closed because of the pandemic. Somehow, all this work came together, and I am especially grateful to the staff of Giles Ltd., the co-publisher of the book with the Maryland Center for History and Culture, who were always agreeable and helpful, quickly responding to changes in text, layout and images. They kept the process moving smoothly. Because the production of the book occurred digitally, we were little affected by the Covid crisis. In fact, quarantine created plenty of uninterrupted time to write and edit the book, which was published in the fall of 2021 as we had scheduled when we started in the spring of 2017.

Tell us about some of the patterns of behavior that are discerned by inventoried household furnishings and tablewares.

Although scholars have done much to define the pattern of material culture in the Chesapeake from early European settlement in the first decades of the Seventeenth Century through the early Nineteenth Century, the Eyre Hall research provided the opportunity to document how those broad transformations in the material lives of those who called the region home actually occurred. This book is a microhistory of those material changes. Archaeological excavations at an early Seventeenth Century site at Eyreville, the home of the cadet branch of the family for more than a century, revealed the beginnings of planter society when earthfast building was common and luxury goods were few. Compared to the second generation of the family who came to maturity in the 1660s and 1670s on this site, the material well-being of the fourth and fifth generation who erected the current house across the creek from Eyreville in the late 1750s would have been unrecognizable to those first Eyres. The estate inventory of Severn Eyre at his death in 1773 was a lengthy list comprising highly specialized tablewares, household goods imported from England and personal items that we recognize as modern, and those that survive to a large degree at Eyre Hall today still serve their original purpose and often retain their social cachet. The grim, post-in-the-ground houses, simple cooking implements and communal eating and drinking vessels made of wood and pewter from the Seventeenth Century were as foreign to those of Severn Eyre’s generation as they are to ours. The modern ethic of self-conscious consumption had become commonplace among the gentry in the late colonial period.

What is the “value added” of having Eyre Hall’s collection housed intact in the residence versus in a museum?

There are only a handful of houses that survive today in Virginia that are still owned by descendants of their original builders, and few of these retain the rich collection of objects and papers as Eyre Hall, housed in a dwelling that is little changed, in a landscape filled with service buildings, gardens and agricultural fields and roads that were laid out more than two centuries ago. We know who purchased most of the furniture, silver, ceramics and books that are in the house today. Through their papers, accounts and family stories, we know something of most of their personalities and understand much about their aspirations to fashion the kind of house that they did in the period between the 1750s and 1850s.

This material culture of Eyre Hall plantation illustrates the everchanging meanings of this place in American culture from the Seventeenth through the early Twenty-First Centuries. The house and its objects, garden and landscape are representative of the cultural endeavors of a deferential society in Virginia that was built on slavery, which suffered the tribulations wrought by the Revolution, Civil War, Reconstruction and several depressions, undermining its social and economic foundations. The history of the people of Eyre Hall and their material legacies might be read in the context of these broader events, which leads to an existential question. How did this extensive collection of documents, buildings, objects and agricultural landscape survive these disruptions? And what does this inheritance mean today in the wake of such transformative events? These are the kind of questions we can ask only in places like Eyre Hall, where that material culture of the period between 1759 and the Civil War remains largely intact.

The construction of Eyre Hall in the late colonial period was an assertion of its builder’s ambition to be a leading political and social player in the affairs of the province. For at least two or three generations when the prestige of the planter elite was at its height, Eyre Hall was a powerhouse that signaled the family’s preeminent status in this slave-owning society. Gradually over the course of the Nineteenth Century with the transformation of agriculture and trade along with the disruptions of the Civil War, the lands at Eyre Hall still produced wealth, but eventually the place became a secondary home, a comfortable retreat. After the first quarter of the Nineteenth Century, few changes were made to the house and its furnishings and the family’s participation in politics seldom ventured beyond the Eastern Shore. In the 1880s, the family left Eyre Hall and settled in Baltimore, returning to the place during the summers and for holiday retreats. In the early Twentieth Century, Eyre Hall was seen as a nostalgic exemplar of an earlier age, a storehouse of family legends and traditions. Preservation and survival rather than expansion, and change became the dominant attitude toward the house and grounds. The gardens became a focus of garden week tours, and the old brown furniture was recognized as prized antiques. The obligation of preserving the house, land and objects became the guiding principle of the most recent generations of stewards. Although the house and objects remained, attitudes about their meaning and preservation have changed dramatically.

The book contains a poignant section dealing with snapshots of everyday life on the farm told by owners, managers and workers at Eyre Hall. Why was this important to include?

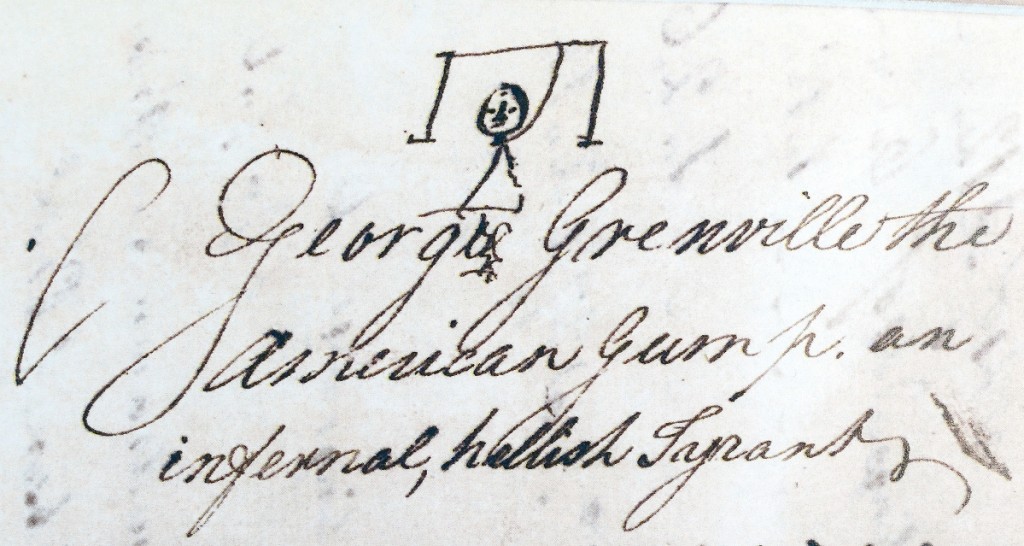

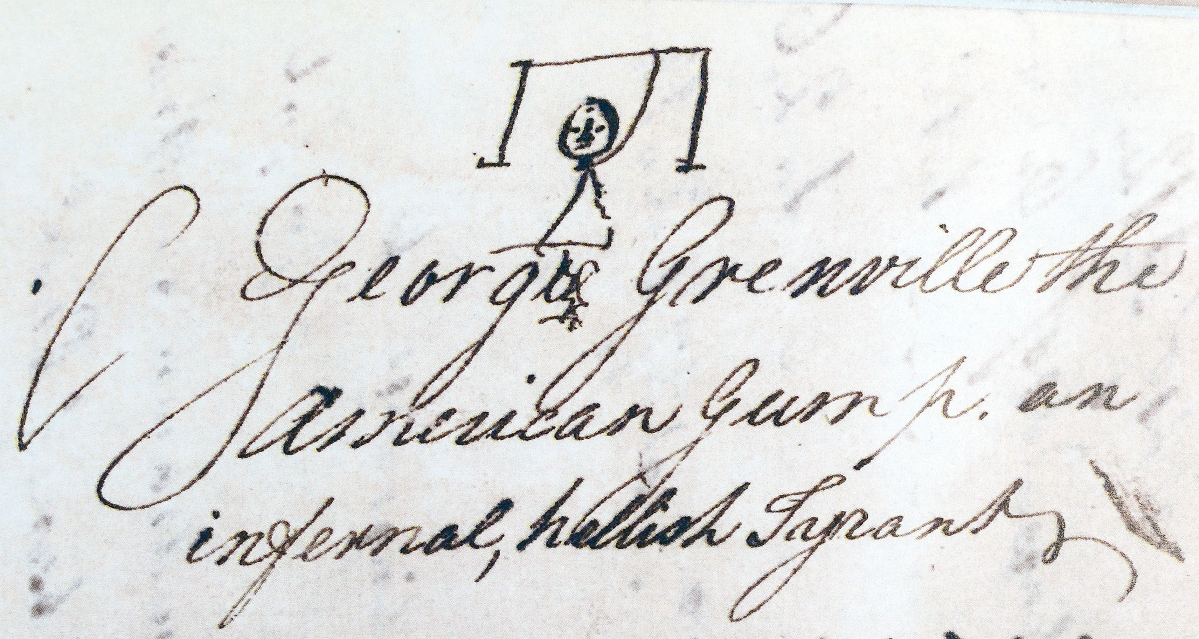

My intention for the book was that it would be more than simply a catalog of decorative arts objects. I would have been the wrong person for that task. What I envisioned was a comprehensive history of one place and its material legacy reflected in the gardens, grounds, buildings and objects and all those who lived and worked at Eyre Hall from the Eighteenth through the Twentieth Centuries. It would illustrate changing social, economic and cultural patterns in this region. For the early centuries, I had to rely on what documentary material I could find to tell the story of this family and something of their social and cultural aspirations and political attitudes. There were very few personal letters that explicitly revealed those thoughts. However, the books they read, the graffiti they wrote on the walls of the bedroom in the garret and the sketches in miscellany books and the family Bible cast some light on their innermost feelings. What better way to understand the ambitions of the young Littleton Eyre, the builder of Eyre Hall, than to see his youthful signature proudly inscribed in the margins of the family’s Book of Common Prayer, with the date and note that he had been made deputy sheriff of the county in 1733. It was the first of many positions of power that he held over the next 25 years. Revealing, too, is the sketch of George Grenville, the prime minister of England and author of the Stamp Act, which Severn Eyre and his father Littleton excoriated in the local courts. Severn drew a picture of Greenville tied to a gallows with a noose around his neck with the phrase denouncing him as “the American Gump, an infernal, hellish Tyrant.”

For the Twentieth Century, we relied upon a different source of historical evidence to uncover life at Eyre Hall when Jim Crow laws made life difficult for the Black residents who worked on the farm for the Baldwin family. I asked ethnographic historian and an old friend, George McDaniel, to interview not only Furlong Baldwin and his cousin Dick McIntosh who have memories of the place dating to the 1930s and 40s, but also the children and grandchildren of an extended Black family whose parents and grandparents had worked at Eyre Hall from the 1920s through the 1970s. From their recollections, we not only got a frank understanding of the relationship between the races but also insight into the transformation of old traditional agricultural practices, such as the replacement of oxen and horses in the fields with tractors. These stories were part of the history that would have been lost had they not been recorded by McDaniel. Sometimes, historians overlook evidence that is not on paper but survives in the oral testimonies of those who lived on the site and through archaeological excavations of buildings and other features that have disappeared. To have ignored these sources would have diminished the richness of the historical record of Eyre Hall.

As you point out, the first generation of Eyre Hall history was not so grand. When do the earliest documents trace the establishment of the homestead?

The origins of the First Eyres on the Eastern Shore is shadowy. The most we know of Thomas Eyre, a surgeon who died in 1647, is his death and his will in which he left a 200-acre farm to the oldest of his three young sons, a few head of cattle divided into three lots and personal items, including a coat, gun and a horse, which he gave to a neighbor. We don’t know anything about his immigration to Virginia, where he came from in England, how old he was, or even his meeting and marriage to Susanna Baker. It was the widow Susanna who was instrumental in shaping the fortunes of her children. Because eligible women were in such short supply, Susanna did not long remain a widow, but shortly after burying her husband, she married a wealthy magistrate, Francis Pott, whose brother had been governor of Virginia for a brief time in the early 1630s. However, Pott died less than a year later, but in so doing left his new wife a large tract of land called Golden Quarter at the lower end of the peninsula near Cape Charles. Before she could mourn her second husband, Susanna was married once again, this time to an even wealthier planter/merchant named William Kendall, who took her children under his wing and instructed them in the business practices of a merchant and tobacco planter and taught them the ropes of a politician. Kendall became one of the wealthiest landowners on the Eastern Shore by the time of his death in the 1686, just a few years after his wife Susanna had died. By then, the sons had established themselves on three large plantation tracts at Golden Quarter, obtained enslaved laborers to work the land, and had secured their positions in an increasingly hierarchical society by marrying the daughters of successful planters and merchants.

What changed with respect to the social stability and mobility of the second and succeeding generations?

The records of Northampton County survive intact from the founding of the county in 1632. As a result, there are very detailed descriptions in the court papers from depositions, wills and inventories that describe a frontier society where life was often short, nasty and brutish. The death rates of immigrants was particularly high, even in an era that saw most children die before they reached adulthood. Marriages were broken up, like Susanna Eyre’s, by the frequent death of spouses. Indentured servants were often rudely treated by their masters. It was difficult to establish a stable society where the bonds of continuity were so tenuous. Violence was endemic and the rule of law was especially weak. Despite these hardships, a very few people thrived more by strong constitutions than by canny business practices. After many turbulent decades, some were able to invest in the future and pass down their wealth from one generation to the next.

Only by luck, the story of the early Eyres did not end in the Seventeenth Century as did so many other early families. As noted above, the three sons of the first Thomas Eyre were fortunate in the fact that they had a patron to steer them through the hardships or their early years. They became successful planters and merchants by the time of their deaths between the 1690s and 1710s. They had become slave owners, merchants and members of either the county court or the parish vestry. From these beginnings, Thomas Eyre, the second son, had two sons, one of whom Severn married into the prominent Harmanson family. Born in the fourth generation, Littleton Eyre was enterprising, aggressive and astute. By the middle of the Eighteenth Century he was one of the leading planters in the county. His wealth grew when he entered into business partnerships that controlled a small fleet of ships. He was member of the House of Burgesses for two decades. By the time he purchased the Eyre Hall land from a distant relative and erected the present house he had reached the pinnacle of Eastern Shore society, a position his descendants retained during the following century and a half.

Is there an Eyreville artifact that is emblematic of the shift from rudimentary colonial household goods to more specialized possessions?

All the objects owned by members of the first three generations of Eyres have disappeared except for a large silver punch bowl – only one of two non-ecclesiastical pieces of Seventeenth Century Virginia silver that has survived. Dated to the 1690s, this London-made punch bowl was given by Bridget Foxcroft to a grand-nephew of hers, the first Severn Eyre, on her death in 1704. Through several generations from the early Eighteenth through the middle of the Nineteenth Century, it can be traced by name through a number of wills and inventories and remains a centerpiece on the dining room table today, but had been remembered through a completely fatuous history associated with a horse winning a race.

As an architectural historian, what was the most interesting thing you learned about Eyre Hall’s relation to other houses of the period in the Chesapeake?

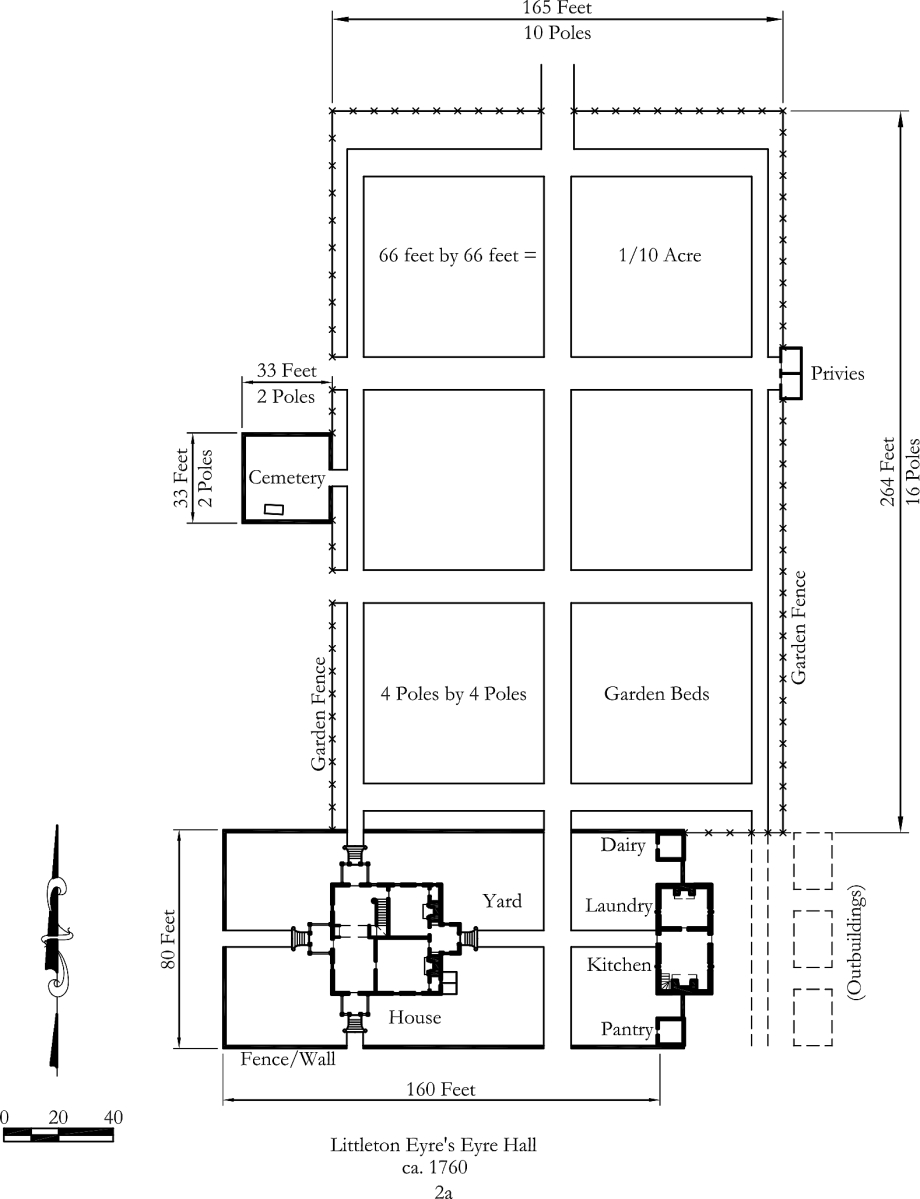

Although Eyre Hall now looks like a strung out arrangement of additions like many other Eastern Shore houses, it truly was a novel design when first constructed in 1759. The plan was a side passage house common in London and other cities, but when placed in the countryside, its proportions expanded to 40 square feet, and the orientation was turned on its side to form an entirely different appearance than its townhouse origins. What I had not realized is that the west gable end of the gambrel roof house was the principal façade with the main entrance being a double door in that wall, which opened into what now appears to be the side-passage of the house. In fact, it was a cross passage. A two-story pedimented portico (though partially rebuilt and now screened-in) defined this gable end as the principal façade. It was one of the earliest houses in Virginia to have a two-story portico. From archaeological probing in the west yard (now seen as the side of the house), we discovered that there was originally an 8-foot-wide gate centered on the portico some 40 feet west of the west façade, which provided a grand entrance to the house. It was only in the early Nineteenth Century when a grandson, John Eyre, redefined the main entrance as the south side of the house when he extended a large wing on what had been the backside. That was a great surprise, but the original design fit with the placement of the garden on the north side of the house, a pattern that Will Rieley, the garden historian, had discovered was true of so many colonial gardens.

-W.A. Demers

The Material World Of Eyre Hall: Four Centuries of Chesapeake History, published by Maryland Center for History and Culture, Baltimore, Md., in association with D Giles Ltd. Limited; ISBN:978-1-911282-91-4, $89.95, is available at the Museum Store at the Maryland Center for History and Culture, 610 Park Avenue, Baltimore, MD 21201; 410-685-3750 extension 377; shop@mdhistory.org; www.shop.mdhistory.org; or publications@mdhistory.org.