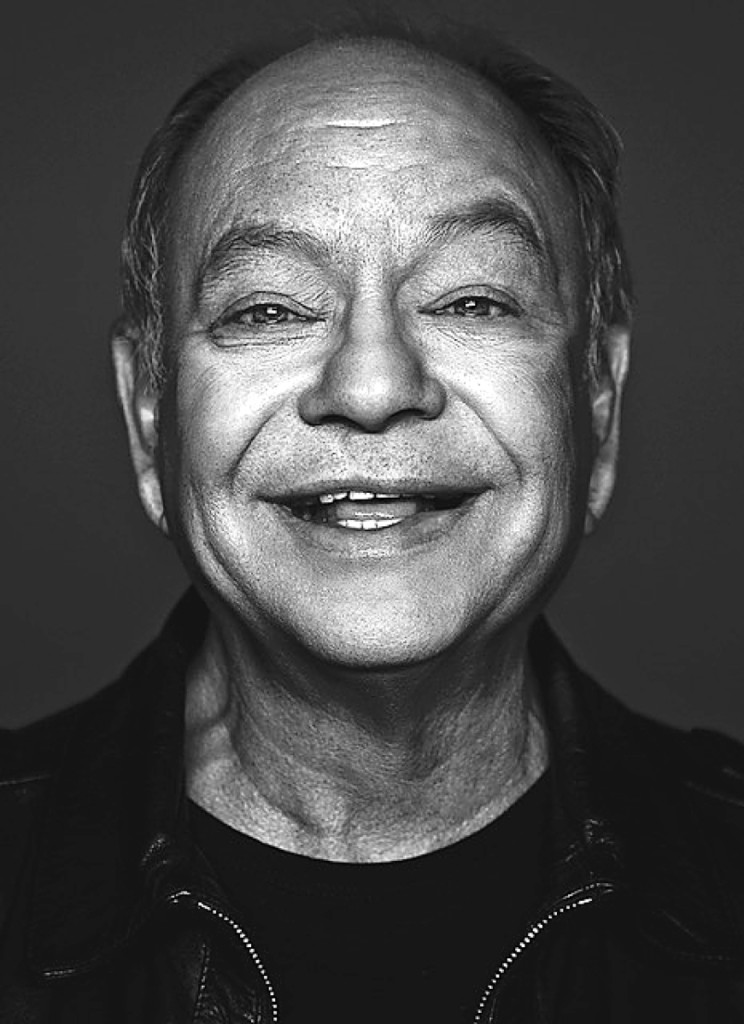

Slated to open this year as the freshest extension of The Riverside Art Museum is the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art, Culture & Industry, to be better known as The Cheech. Its namesake is Cheech, the actor-turned-art-collector who has amassed among the largest collections of Chicano art on Earth. The artists, the history, the images, the sabor – all of these speak to Marin, now 76, through his lived experiences and into his dreams, where they dominate his psyche. We caught up with Cheech to talk about collecting, his dreams and what the museum will accomplish.

Do you have a process when collecting?

It’s a process of seeing new artists, seeing new work from old artists, or tracking down the ones that got away. I learned a lot from my days of collecting Art Nouveau and Art Deco. When you’re discovering Chicano art, you’re learning.

What were the earliest pieces to enter the collection?

The first pieces I bought were in the mid-1980s, I bought three at the same time, one each by George Yepes, Frank Romero and Carlos Almaraz. I have never sold a piece from the collection.

The last piece you bought?

The last one I bought was the one that got away: a work by Benito Huerta.

Tell me about your earliest days collecting.

I started in Art Nouveau in the early 1970s and I was lucky because I was traveling then. I was on the road all the time. That was my program, I would get into town and whip out the yellow pages and go through the antique dealers and judge from the ad, call them up and say, ‘do you have this?’ If they did, I’d be right over – I was obsessed. I would buy something really good like a Gallé lamp and then carry it with me as I traveled. Some of them are really big, sometimes I had to buy an extra seat for them. What I learned is that if you see a really good piece and your eye is educated and you can buy it, do it then, the next time you come around it won’t be there. There are a couple pieces in the Chicano collection that got away from me. Back to that spectacular painting by Huerta, it’s a big beautiful painting on velvet. I was at a show and saw it, didn’t buy it, went around the show and it was sold by the time I got back. The guy who bought it died and the son heard I liked these things.

Are there any groups represented in the Chicano collection?

When you can find them. The first group I collected was Los Four, that was Carlos Almaraz, Frank Romero, Roberto de la Rocha and Gilbert Luján. They pictured themselves as the new American art. Another group called Asco, that had more of a punk influence. If I find an artist I really like, I start collecting in depth from that artist. There are some artists I have 25 to 30 pieces and others I have only a couple.

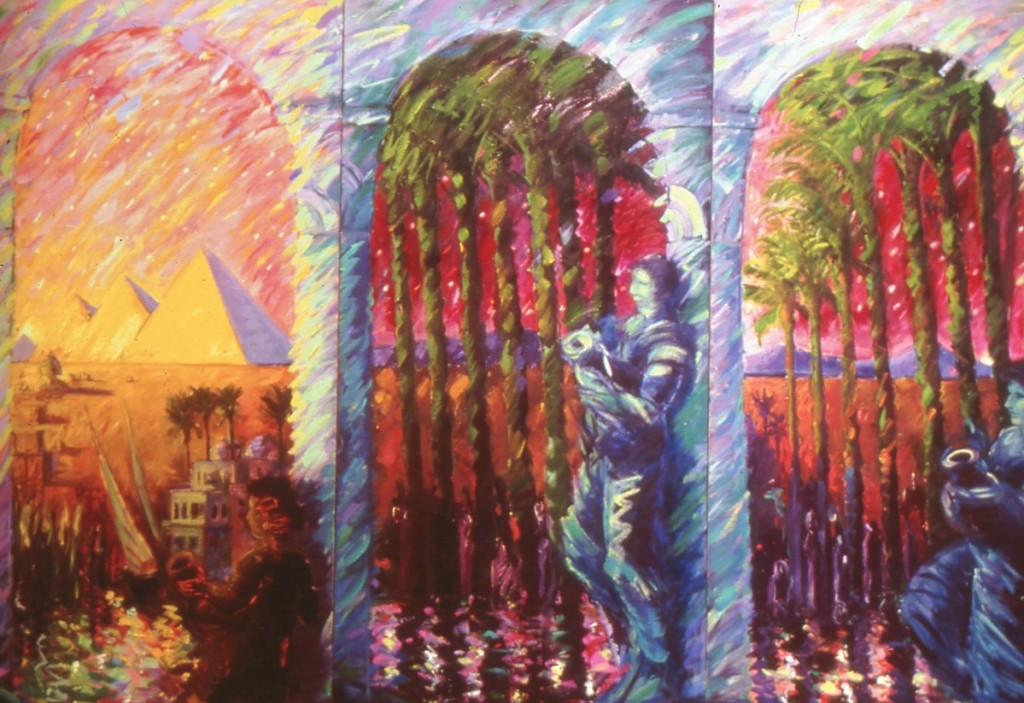

Any murals in your collection?

Not off a building, but some pieces that are mural sized. There’s a piece by Frank Romero called “Mexico Mexico,” it’s 12 by 24 feet.

Will there be an aspect of murals within the museum?

There might be, it’s hard to take them off the wall and put them into the museum. There will be instruction on them, because it is an academic center as well as a paintings collection.

What do you believe to be the most significant work in the collection?

Generally, anything that I have by Carlos Almaraz. He’s passed on, it’s a finite market. But that’s like choosing your favorite child, the ones that are giving you the least amount of trouble at the time. There’s a new documentary on Almaraz on Netflix called Carlos Almaraz: Playing with Fire, it’s one of the best documentaries of the year. I think everyone in Carlos’ family participated.

Does Chicano Art begin with El Movimiento? In what ways is it still the same?

Chicano art started as the arm of a political civil rights movement. They were the sign makers, the poster makers, the backdrop makers of Cesar Chavez and everyone in the field. That kind of tradition of all of the Chicano artists I collected, they start out there. The first works are news from the front, what my community is involved in right now. There are artistic concerns, but usually its news from the front, that signals the advent of other painters who are painting in this tradition. The political front of it is in conjunction with the movement of civil rights for Chicanos.

What do you remember about El Movimiento from your childhood?

At some point, if you march you better duck. I was more involved in the draft resistance movement. It was going on at that time as well, led by David Harris. The feds wanted to talk to us a lot, I didn’t necessarily want to talk to them. I had a lot to say, so I wrote it on the back of my draft card and sent it to them. You can see it happening right now in the country, people are out in the streets, they want to have a soul that they believe in.

What does Chicano art created today look like?

It’s like taking a camera and focusing on their neighborhood, and they all do that. At some point they’re gentle and at others more aggressive. Chicano art has a bunch of different aspects to it. Whether its familial or general or religious-based or abstract. We put all these aspects together and you get the whole 360 of what this community looks like. I call it the sabor. The flavor of the community.

What about politics?

All artists have a political involvement, it just depends on the events. I think there will be a lot of Trump art coming out of all aspects of society. That political aspect – we will not be afraid of expressing those opinions. It’s not all political art, though. We don’t live our life totally politically 24/7, we just include that in.

How has the sabor changed over time?

It’s usually voiced by the next generation coming in. Chicanos always have more kids. They give birth to Latinx or whatever the kids are doing. They’re not specified to any subject matter or area of expertise, it’s all over the place. You want to express pride in your community. Make up your own means of expression that speaks to where you come from. The artist understands that. It’s not to be encumbered by any definition, but it’s to use that definition to spread the word. When you put all these viewpoints together, you get the feeling of the sabor. I collect the paintings and these artists come from a long painting tradition. The Chicano artists are different in that they never gave up the brush. Painting has come in and out of vogue, but it’s good. It goes back into my urge to have everyone see paintings in person. You cannot understand paintings unless you see them in person because of the nature of the medium and you have to get up close, it’s a handmade art. You can’t love or hate Chicano art unless you see it, and that’s been my goal, to get everyone to see it.

Why is Riverside a good site for the museum?

They came to me with this proposition. The Inland Empire is one of the largest concentrations of Latinos in the whole country. The county is 51 percent Latino, who identify, and 50 percent other. And they get along because they’ve all grown up together. The city had this building, a town library, a beautiful midcentury building right next door to the historic Mission Inn, a national historic monument. They needed to repurpose the building, and that need just happened to coincide with a Chicano works on paper show at the Riverside Art Museum, the biggest show they ever had. The city manager had the idea to give Cheech the building and he’d bring the collection here. I didn’t understand it at first, I thought, ‘like you want me to buy the museum? I’m doing okay, but maybe not museum okay.’ But they said they want the collection and it seemed to work out. What I didn’t realize then is it’s a lifelong commitment to fundraising.

What does your involvement look like in the years ahead?

I’m very aggressive, we can go this way or that way. I just had a conversation with Robert Rodriguez, a friend of mine, and he has this program that he just took to Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, called How To Make A Movie With $7,000. It teaches you to do everything: writer, director, you’re the cable guy, everything. You know what everyone does. This program, he’s going to bring to Riverside and we’ll start to see the longevity of that program there. We’ll have a lot of programs like that.

You aim to show others how to create?

Yes, that’s an aspect, but also expanding the field and teaching them to believe they can compete. You’re not just sitting home and making drawings and hoping someone will see them, but enlarge the area where someone can enter their art and be a part of. It’s a process to let them in. Now, I think it will happen. It is my belief that Chicano art is the most significant and long-lasting descriptions of any culture or art group that has existed in this country. It’s ongoing and it has been there for more than 50 years with a long continuing tradition.

What themes in Chicano art do you find most alluring?

There’s always the naked women. Chicanos like to do that a lot, but so did Da Vinci and Caravaggio. That seems to be a theme among painters. Some of the best works are those, but it is also messages from the front. That’s what really excites me. I’m not adverse to sort of scary works, Chicano art has a scary aspect to it. Confrontational images. The early part of it more likely than not. Any painting associated with the Chicano Moratorium or any political agenda in those cities, you get it. It all depends on the painting. Recognizing or falling in love with a painting is like being mesmerized. You stand in front and you go ‘mmmm’ and then it reaches out and gently grabs you by the throat. The paintings generally have to enter my dreams, and when they do, I know there’s something there and I’m engrossed with them. Then I buy them and put them on the wall. It happens instantly and sometimes over a long period of time. Some painters haunt my dreams for years. The only thing I think about after that was ‘what took you so long?’

How long ago did you run out of wall space?

I couldn’t even put up the first painting I bought. It was 12 by 24 feet, I had no space for it. But at the time I lived in this little Hansel and Gretel house in Malibu, it was beautiful. I lived there for 40 years, but no wall space and I had a growing collection. When I finally moved out of there and into a new house, I always found houses that had no furniture in them. That was the only way I could imagine paintings in there. As soon as I found the one, I bought it and installed professional track hanging throughout the house and that’s made all the difference in the world.

What will the first show at The Cheech look like?

Colorful. It will feature the De La Torre brothers, they have an interesting blend of Mexican/Danish and are really getting a lot of attention all over the world. They were originally glassblowers, but very rococo and Chicano glass figures. Slowly they have developed lenticular art and they have made it a true fine art form. They will be the opening show and they will create some art that will be left at The Cheech at the entrance to welcome visitors. Then the Smithsonian will take that opening show and tour it. We’ve been having these Zoom meeting dialogues with prominent Chicano artists of different categories, a few weeks ago I spoke to Carlos Santana. We’re looking at Mister Cartoon, a top tattoo artist, and Lalo Alcaraz, who creates La Cucaracha, a syndicated cartoon strip. It involves the community and gets them excited. I want to bring joy to the city of Riverside.

Is this the final chapter? Will you do this for the rest of your days?

I think so. I’d like to expire before I retire, though, the great artist knows when he’s done.

-Greg Smith