A recent addition to the growing team at Phillips is David Norman, named chairman of the Americas, who brings with him more than 30 years experience in impressionist and modern art, referred to those in the know as “imp/mod.” During Norman’s tenure at Sotheby’s, which was followed by a brief stint as an independent advisor, he was involved with the sales of three works that broke the $100 million record for their respective categories. Antiques and The Arts Weekly caught up with this “$100 Million Dollar Man” for his thoughts on the field, looking both backward and forward.

How has the market changed since you started?

The most marked change has been the incredible growth and diversification of the collecting population. When I started in the mid-1980s, it was vastly more limited, with the market particularly reliant on Japanese bidders – and consequently very vulnerable to the loss of their buying towards 1990. Today’s market is much broader both geographically and by sources of wealth, especially in Asia. I believe that because demand is now coming from so many different sectors and parts of the world, the market is the strongest it’s ever been and more resilient during economic downturns.

Are there trends that have remained consistent?

The interest in quality. Even as tastes in collecting change as new generations enter the market – evidenced most prominently by the explosion of interest in contemporary art – demand always rises to meet the supply of great works. Average works by impressionists are not as desired as they were when I started, but a real “A” quality impressionist or post-impressionist painting, the kind you would expect to see in a major museum, will not only sell, it will smash records.

Surprising market trends?

One trend that started about 20 years ago was a keen interest in the late works of an artist’s career. Just take a look at what’s happened to Picasso’s market. Long considered the products of less creativity, skill and over-production, the post-1960s works by Picasso have gone through a massive reevaluation. Instead of being perceived as simply work created by Picasso at the tail end of his career, they now seem foundational to the contemporary expressionist works of the 1980s and forward. A great late Picasso lives beautifully next to a major Basquiat in our galleries. The same can be said for many artists, such as Matisse and Miró.

You’ve been connected with three works that broke the $100 million mark: in 2004 with Picasso’s “Garçon a la Pipe,” in 2010 with Giacometti’s “Walking Man 1” and in 2012 with Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.” Is the current imp/mod market ready to deliver similar results if the right work came along? Do you feel pressure to deliver that for Phillips?

We will definitely continue to see new records for masterpieces – it’s the nature of the business. In the not-so-distant future, I can imagine the gavel coming down on a billion-dollar painting. And as for pressure? Always! Regardless of where one is, pressure is a great motivator and driver, and I try to embrace it. More pertinent to my new role at Phillips, I would say it’s eagerness to be a part of a great growth story. Phillips has experienced tremendous growth in the past few years, including in the modern category, and I want to make my contribution to that effort.

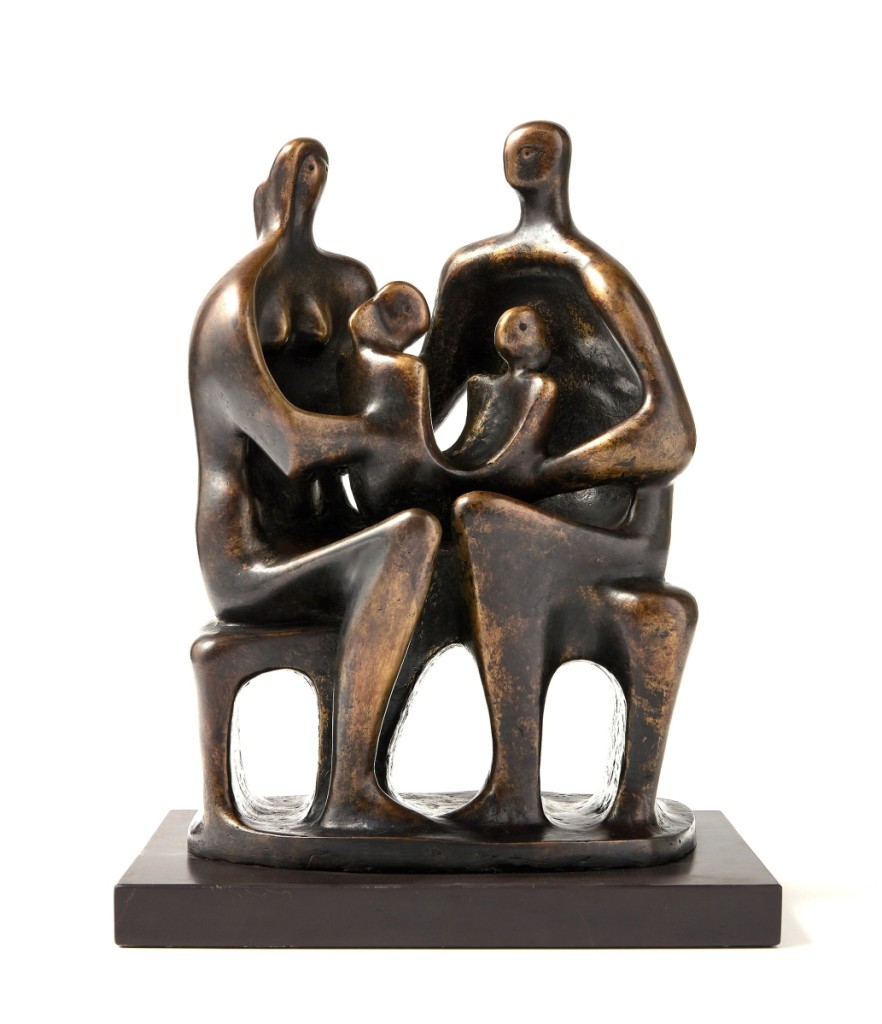

Henry Moore (1898-1986), Family Group, bronze, height 16 inches. Executed in 1947, this work is from an edition of seven. To be sold November 14 in Phillips’ Twentieth Century &

Contemporary Art evening sale ($2.5/3.5 million).

You started your own art advisory firm in 2016. Why did you give that up to rejoin a large company like Phillips?

I really enjoyed the freedom and flexibility I found working on my own. But I grew up in this business working with colleagues – being mentored by great experts, enjoying strong relationships with peers and, in turn, mentoring the next generation. I missed being a part of a team. During my time working privately, I frequently consulted for Phillips and witnessed first-hand the remarkable turnaround being orchestrated by Ed Dolman and his team. This may sound like a cliché, but I really fell for the “one for all, all for one” spirit here. When Ed suggested I join the team permanently, it didn’t require a great deal of soul-searching to say yes.

The imp/mod departments at your two leading competitors are fairly large. Does your appointment signal that Phillips plans to bump up their staffing in that segment of the market?

While we don’t plan to build a separate department, we do want to expand the offerings in our sales to offer the full breadth of artistic achievement of the last 100 years. Our goal is to create strong visual and emotional connections between painting and sculpture from the modern, postwar and contemporary periods. While walking around Phillips’ galleries, you can clearly see a consistency in our offerings and the continuum of modern artistic thought in the way a Picasso interacts with works by Willem de Kooning and David Hockney.

What are your top priorities, and how will you realize them?

I have several priorities. First, I want to work with my colleagues to secure great works of modern art that naturally integrate with the masters of the postwar and contemporary periods and increase the value and substance of our auctions. To accomplish that, I need to make sure that the many modern collectors I’ve worked with over the years understand what Phillips has to offer. While these collectors know of Phillips, not all have walked through our doors and participated in our sales. It’s my mission to engage them, get them to know us, and make them understand that many of the best people they knew from the other houses are now at Phillips.

Care to make any predictions for the imp/mod market?

While people will always love impressionism, I see a trend towards a diminishing audience for the middle and lower ends of the market. That will continue. As I mentioned earlier, records will continue to be broken for top works, and there will be a continuing rise in values for the late work of some artists that have historically been undervalued. In addition, I believe the art of female artists will continue to attain greater and long-overdue appreciation and value. And we will keep finding new audiences for great art as global wealth expands to new regions of the world. In my career, I’ve seen that newly wealthy individuals tend to buy the art of their own nations first, before moving on to art by more international greats.

Madelia Hickman Ring