Cassandra Sohn photo

Regular readers of this feature know that its subjects are generally collectors, trade personalities or museum folk embarking on a new role at a cultural institution. There are occasions, however, when it is appropriate to feature a newsmaker of a different sort, one who is ending their tenure, and such is the case Donna Hassler, who recently became director emerita of Chesterwood, a site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, marking 14 years of raising the profile and visibility of Daniel Chester French (American, 1850-1931) and Chesterwood. She officially retired on September 30 after completing several part-time curatorial projects this past summer. Antiques and The Arts Weekly caught up with her to review some highlights of her 39 years in the museum field.

At Chesterwood, you’ve rehabilitated buildings, organized traveling exhibitions of French’s sculpture, published a biography and a documentary film on French and expanded the site’s seasonal programming. What’s your next chapter look like?

Well, I am still finishing my chapter on Daniel Chester French and I will always consider myself a student of French, because there is so much more to learn about this prolific sculptor. Since 2020, I have been working with the staff at the American Federation of Arts and my colleagues at Chesterwood and the Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park on a traveling exhibition featuring sculpture from both collections titled “Monuments and Myths: The America of Sculptors Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Daniel Chester French.” I contributed to the illustrated scholarly catalog for the exhibition, which opens on May 30, 2023, at the Jule Collins Smith Museum at Auburn University.

I’ll remain active in the art and museum field as a consultant and volunteer, find time for my own creative writing projects, travel to artists’ homes and studios here and abroad and visit my two young grandsons, Jack and George, who live in the Boston area.

There is a significant difference between leading a historic house museum and one that has an artist residency center component. In fact, you devised a strategic plan to “re-imagine” Chesterwood in the Twenty-First Century as a “Site for Creativity.” What has been involved in making this transition?

When the leadership of the National Trust for Historic Preservation asked me and my fellow site directors to “re-imagine” their historic site, my first thought was ‘What is Chesterwood and why was it created?’ I had recently discovered French’s wife’s last will and testament. In it, Mary Adams French stated that if her daughter, Margaret French Cresson, predeceased her, she wanted to bequeath the property to the American Academy in Rome, so that academy fellows may use it as “a place of work.” Here was my answer! Chesterwood is a place of creativity and inspiration, where artists could live and work once again and engage visitors in understanding the creative process. French created his artist’s retreat inspired by the natural beauty of the Berkshires, not only as a place to complete his work, but to share his ideas and passions with family, friends and the community. Envisioning a “Site for Creativity” with a public component, funds were raised to rehabilitate several buildings on the property, including French’s studio and residence before a year-round residency program could begin.

You also transformed the site’s 44-year-old annual outdoor sculpture exhibition from a juried show to a curated selection process. How did you do that?

Chesterwood is one of the earliest venues in the United States to showcase sculpture outdoors in a natural setting, and more than 600 artists have exhibited their work on the property since 1978. Hiring contemporary art curators to select the work brought new, internationally recognized sculptors and a variety of sculpture in different media to the site. For example, one of Chesterwood’s most interesting and popular exhibitions, “The Nature of Glass: Contemporary Sculpture at Chesterwood,” was curated in 2016 by Jim Schantz of Schantz Gallery Contemporary Glass. Schantz invited 12 artists from across the United States working in blown, constructed and cast glass. His knowledge of the latest technologies in glass allowed us to host our first exhibition on the grounds in this medium.

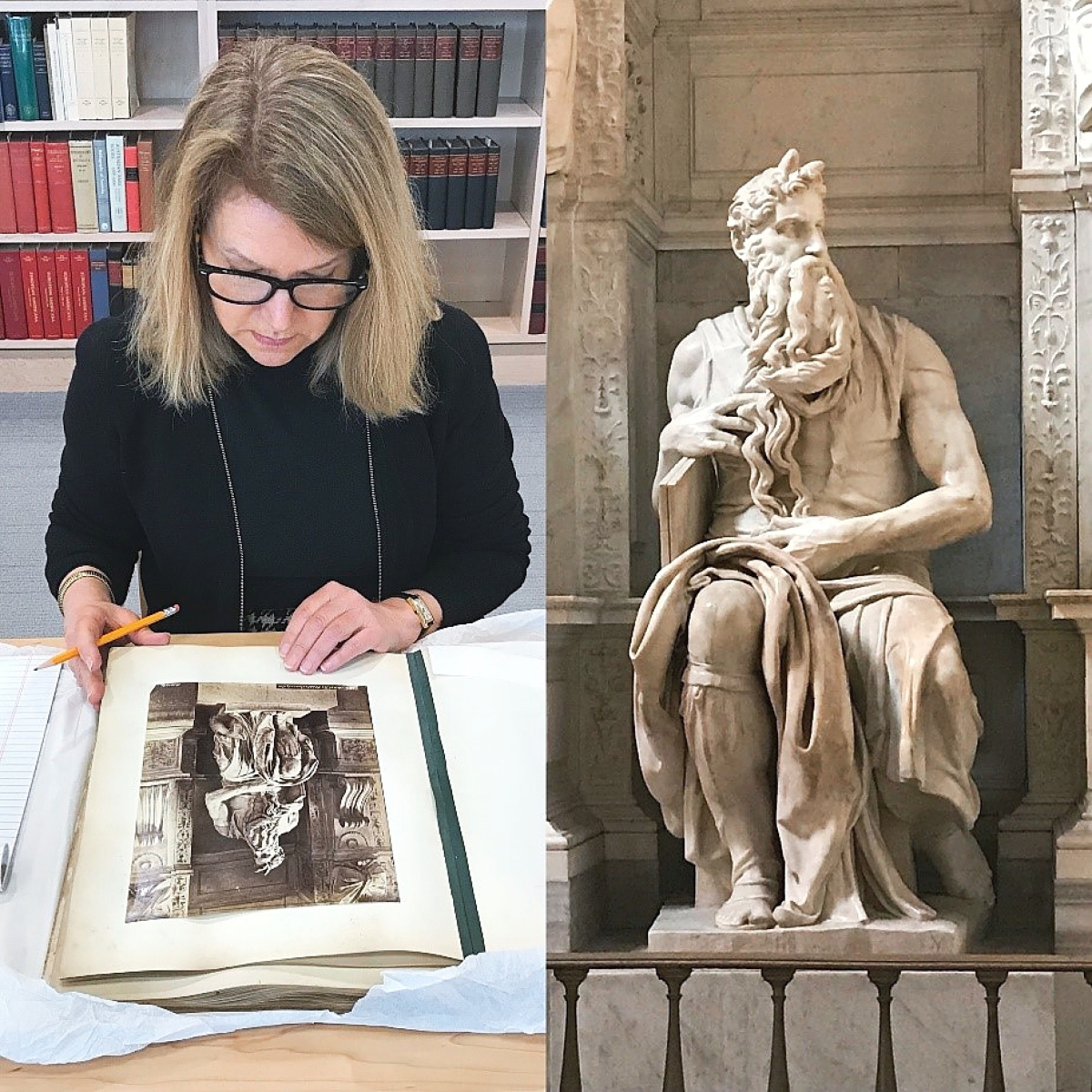

In early 2018, Donna Hassler was researching Nineteenth Century black and white photographs of Italian buildings and sculpture collected by Daniel Chester French in preparation for a month-long study trip at the American Academy in Rome as an affiliated fellow of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Aside from being known for his 1874 “Minute Man” sculpture in Concord, Mass., and his 1920 monumental statue of Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC, what else should we know about French?

Daniel Chester French was highly proficient in modeling the nude female form. From his earliest reclining female figure “Memory” to his final sculpture “Andromeda,” both carved in marble by the Piccirilli Brothers, French also incorporated the female form as allegory in many of his public monuments, including the John Boyle O’Reilly Memorial, the Milmore Memorial, the Richard Morris Hunt Memorial, the Four Continents, the Melvin Memorial, the Spencer Trask Memorial, the Admiral Samuel F. Dupont Memorial and the First Division Memorial.

In 2016, Chesterwood and the Boston Athenaeum co-organized a groundbreaking exhibition, “Daniel Chester French: The Female Form Revealed,” and Athenaeum curator Dr David Dearinger put together a comprehensive catalog. Presented at the Boston Athenaeum, the exhibition brought together the artist’s plaster maquettes and models of the female figure for the first time. It was refreshing to experience French’s sculpture in a new context, with his “Minute Man” and “Abraham Lincoln” nowhere in sight!

French was also very involved in New York artistic circles as a life member of the board of trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and chairman of the sculpture committee. He was also a founding member of several art organizations, including the National Sculpture Society and the American Academy in Rome as well as a mentor to young artists, such as Evelyn Beatrice Longman, who would go on to have a successful career.

When Daniel Chester French lived at Chesterwood, he also enjoyed sculpting the formal gardens as well as the woodland walks. The rural property replete with farm animals, vegetable beds and fruit trees had become a gentleman’s farm despite himself, French once wrote.

French was also skilled in pastel drawing and oil painting, and he enjoyed making portraits of family members and women he encountered who caught his eye.

What other ways have you championed French’s legacy?

Since 2007, Chesterwood has been the home of the Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios (HAHS) Program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. HAHS is a membership consortium of more than 50 homes, studios and site installations of American artists that are open to the public and have been preserved and interpreted where their art was created.

As the administrator of the HAHS Program from 2008 to 2021, I represented Chesterwood and French’s legacy by cross-promoting the HAHS sites through marketing, organizing several HAHS workshops and developing the website www.artistshomes.org. I was also pleased to promote French’s legacy by commissioning noted photographer Don Freeman to photograph French’s Studio for the cover of Valerie A. Balint’s Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios (Princeton University Press, 2020).

When you prepared for a 2018 residency at the American Academy in Rome (AAR), your project was to retrace the footsteps of Daniel Chester French in Italy as a student in the 1870s. What was that experience like?

I still remember the day I received a phone call at my office from David Brown, executive vice president, National Trust for Historic Preservation, inviting me to participate as an affiliate fellow of the National Trust at the American Academy in Rome. It was a dream come true, and I sat frozen in my chair in disbelief. For years, I had thought about attending the AAR, to retrace the footsteps of the young sculptor in Italy and to learn how successful residency programs operate, especially one that French himself helped raise money for to support his friend, the AAR founder and architect, Charles McKim.

With my Chesterwood colleague, Dana Pilson, who was a visiting scholar at the AAR, we prepared for our trip to Italy by studying French’s archives (now at the Chapin Library, Williams College), which included Nineteenth Century commercial photographs by Alinari that French had purchased. The photographs included images of Italian cities as well as sculpture by artists French revered, such as Donatello and Michelangelo. We visited the places that interested French, read his journal entries about what he saw and where he went and came away with a new understanding of the fledgling artist abroad.

Donna Hassler at the Chapin Library looking at one of DCF’s photos of Michelangelo’s “Moses” and a photo of the sculpture itself.

You describe your AAR fellowship as one of the highlights of your museum career. How so?

Having the opportunity to step back from my daily activities at work as an administrator and curator and live at an artist residency in Rome for a month was, indeed, one of the highlights of my museum career. My research objective was two-fold: firstly, to learn more about Daniel Chester French and his artistic style and sensibilities, based on the ancient and Italianate art and architecture as recorded in his journals and letters. Secondly, to learn first-hand about what made the AAR successful as a dynamic residency program. An unexpected bonus to the experience were the freshly prepared meals from local ingredients created for the residents and visiting artists and scholars by Alice Waters’ Sustainable Food Project.

What other sculptors, either American or foreign, have captured your professional interest?

When I was working on a catalog of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s American sculpture collection early in my museum career, I went to Paris for three weeks to research the artists who studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, such as Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Chesterwood, in fact, holds one of his most beautiful plaster bas-reliefs, a profile portrait of Sarah Redwood Lee. It was a gift from the artist to Daniel Chester French. I also admire the sculptors who were Saint-Gaudens’ assistants before they also studied in Paris, including Frederick W. MacMonnies, James Earle Fraser and John Flanagan. Some women sculptors of that era I admire are Harriet W. Frishmuth, Malvina Hoffman, Anna Hyatt Huntington and Bessie Potter Vonnoh.

While serving as a founding member of the board of trustees of the organization that preserved Paul Manship’s home and studio in Lanesville, Mass., as a residency center, I developed a further appreciation for his work.

What draws you to the Berkshires?

I have lived in Washington, D.C., New York City and Saratoga Springs, N.Y., but for me the Berkshires holds what Richard Florida coined as the “quality of place.” American artists, writers and performers have been coming to the Berkshires for centuries, inspired by the natural beauty of the landscape, kindred spirits and the time and space to work in a rural environment. I am very fortunate to have found a place rich in art and culture with first-rate institutions, such as the Clark Art Institute, Jacob’s Pillow International Dance Festival, the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, the Norman Rockwell Museum-The Home of American Illustration Art and Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. It is an easy day trip from here to Boston or New York too!

-W.A. Demers