Dr Susan Holly presenting “The Curious Case of Silas Deane” at the Webb Deane Stevens Museum.

Dr Susan Holly is a senior historian at the US Department of State who delivered a public lecture, “The Curious Case of Silas Deane,” in the Webb Barn of the Webb Deane Stevens Museum in Old Wethersfield, Conn., on September 21. Holly presented the controversy surrounding this forgotten founding father, who has been the victim of severe character defamation throughout the past centuries, with her own research and opinions independent of the State Department. This study is, as executive director Brenton Grom commented, “a fascinating opportunity to engage with a human story,” that addresses key questions about how political dysfunction and media bias can create a historic pariah. Holly’s lecture was part of the museum’s series of special events leading up to the United States’ 250th anniversary in 2026, which will raise yet more questions about how to appropriately celebrate American nationhood in the Twenty-First Century. We corresponded with her following the lecture via email.

How did you first become aware of Silas Deane’s story?

During my first few weeks at the department, I was assigned to write a short History of the Department of State for one of our weekly publications, even though I wasn’t working in the Office of the Historian. I have a very clear memory of standing in the stacks of our library and reading about Deane’s trip to France under an alias before Benjamin Franklin’s arrival. I had never heard his name before and was immediately intrigued, because the general consensus was that there wasn’t all that much to say about the first diplomatic mission to Paris since so many documents had been either lost at sea or stolen by the British. I added Deane to my short history, and I never forgot him.

In your lecture, “memory” and “history” are indicated as two key factors in understanding Deane’s legacy, please tell us more about that.

The past plays a part in our lives in two different ways: History, primarily derived from official documents and accounts generated by participants in events; and the individual Memories of people of what they read, saw, heard or felt about a person or an event. (9/11 is a good example.) History and Memory combined paint a picture of the past for future generations.

Both History and Memory play a part in how and what we learn about Deane today. At the time, his enemies worked overtime to blacken his character so that when he is remembered at all, he is remembered as a traitor. Because he was so widely thought of as a traitor, Jared Sparks — the first historian who compiled these documents — drastically edited most of the documents Deane wrote, dismissing his evidence. Sparks decided that what happened was a conflict of personalities with no lasting significance to History, and he felt justified in leaving both Deane’s defense and his counter charges out of the record.

Our view of his past — what we learn and remember about him — consists almost entirely of this negative Memory of Silas Deane.

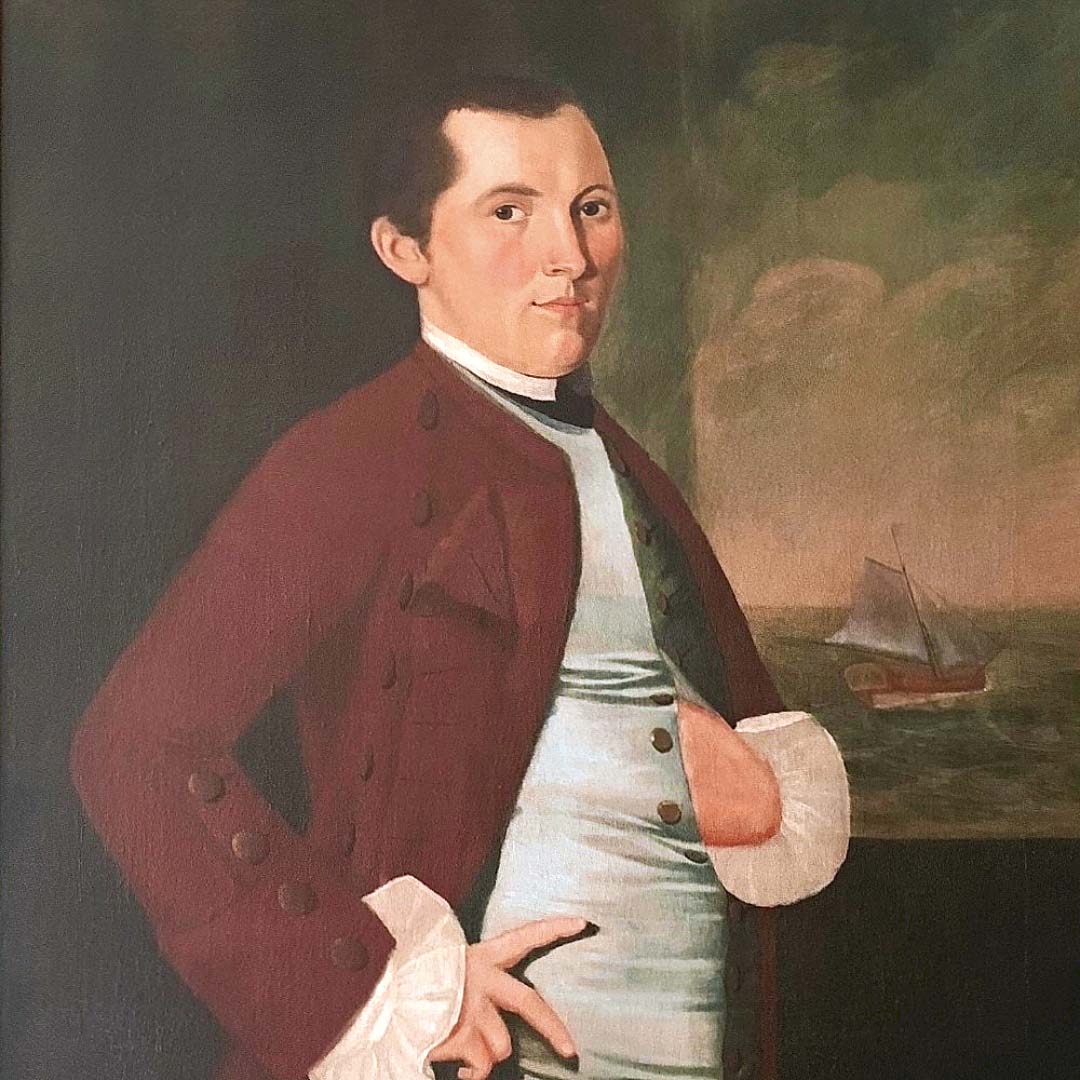

Silas Deane, circa 1766. Image courtesy of the Webb Deane Stevens Museum.

Why do you think this injustice to Deane’s character has been allowed to stand for so long?

Honestly, I think it’s because the vast majority of people don’t even know his name anymore. There are several very good biographies of Deane which lay out much of his story, but people aren’t going to read them if they don’t even know who he is. Remember, John Adams went through Deane’s financial records right after Deane returned to America and found nothing out of order. That didn’t do anything to stop the allegations.

What is the next step for this project?

The department has two versions of compilations dealing with Revolutionary diplomacy; one from 1829 followed by an improved version in 1889. Obviously, it’s been 134 years and many more materials are available now. In 1889, the New-York Historical Society was only in the middle of publishing Deane’s papers, so they wouldn’t have been consulted. It’s our intention to incorporate a wider variety of sources, since having more documents makes for better history. We’re also expanding our perspective by looking at the non-traditional impact of both the enslaved and Native American populations on diplomacy.

What can politicians today learn from Deane’s experience?

Well, I’m not sure what politicians can learn, but I think there’s a positive message for the rest of us. We’ve been through some contentious periods of history when things looked bleak, but as a country we got through it. People don’t always realize how tough it was in the early days to work together and create a government, but the United States pulled through. I like to think that History and Memory agree on that point.

With the semiquincentennial on the horizon, what is your greatest goal for this study?

I think I have two. The first is to present an expanded compilation that provides a wider variety of source material for historians and readers of history. More inclusive history is better history. The second is Deane’s story. He needs us to tell his story — finally. Life wasn’t a victory for Silas personally, but at the end, he was on his way home, and in spite of everything, optimistic about his future. I like to think that even though he died on board ship, he was happy in his final hours. It’s our job now to bring his memory home.

[For more information about the Webb Deane Stevens Museum’s 250th anniversary events, www.wdsmuseum.org.]

—Z.G. Burnett