By day, Dwight M. Cleveland renovates Chicago’s historic Victorian properties in the Near North Side, sparing them from the wrecking ball and helping to maintain the charm of the city. “I’m a slave to nostalgia,” he says, hinting at the drive that has built his collection of more than 3,000 Hollywood movie posters and related cinematic ephemeral advertising over 43 years of collecting. The Norton Museum of Art has mounted “Coming Soon: Film Posters from the Dwight M Cleveland Collection,” on view through October 29 and billed as the most expansive exhibition ever put forth on the subject. Antiques and The Arts Weekly sat down with Cleveland to talk about the exhibition, his collection and how the genre has evolved over time.

Do you remember when you first became interested in movie posters?

I went to the Brooks School in North Andover, Mass., and the art teacher there, who happened to be my dorm counselor, was a very well-known movie poster collector at the time. I graduated from high school in 1977. He had posters up on the walls of his gallery, his studio and his home, and all of us were exposed to these on a daily basis. I never really appreciated them. I wasn’t a film fan or anything like that. And he came back one day from a buying trip and had this little group of lobby cards, which measure 11 by 14 inches, and we were all standing around looking over his shoulder as he was leafing through them. There was a very specific one from Wolf Song, which was a 1929 film with Lupe Veléz and Gary Cooper, and it just shouted out at me, “take me home!” I just fell in love with the card, the graphics, the color saturation and the design, and I really wanted to own it. After graduation I took a gap year before going to college. I moved to Los Angeles. All of the major poster shops were still in business out there – the two fiefdoms of poster art were New York City and Los Angeles – so I got to know a lot of the collectors and dealers out there from the get-go. I would go around to all the shops and I would have this professor’s want-list with me, trying to find posters or cards that were on it that he would be willing to trade. The Wolf Song card was not for sale – people did not really sell at the time – you had to trade for them. It took me about 18 months and I finally got enough items that were on his want-list. It was a combination of things. I worked for a US senator in Los Angeles at the time and was then transferred to their Washington office. I picked some posters up in the Washington area, and then I went back to North Andover armed with all these goodies, and I made a trade with my professor for that card. In the meantime, I had already started to like everything, so I started accumulating. It was an 8-for-6 or something like that. I got my card and he got what he wanted, and it was off to the races from there. It’s been a great love affair for 43 years.

Is trading still common among collectors?

It is, though it has died off. To be honest with you, back then, posters in catalogs or stores were $25, $35, $45. Every once in a while, there was something for $75. It rarely broke $100. If you were trading 4-for-3 and someone kicked in dinner or $20, no one was getting into too much trouble. As prices have risen over the last several years, since the early 90s, if you’re trading a couple posters for $1,000 each and you’re off by 10 percent, it’s starting to get into bigger money. I still do make trades and I like making trades, because when we sell and we auction things off, there are transaction costs. I would much rather make a trade with people, and I always sort of have a couple irons in the fire there, but it’s mainly with old timers who feel the same way that I do. Part of it is the rarity of these works. A lot of these works are one of a kind. Some of us who have been around now for almost half a century – we have been out there turning stones over, in my case 43 years. There isn’t an auction or dealer catalog or internet catalog that I don’t see, and I scan eBay every day. I’m constantly out there on the prowl so I know what has come up. And I know when I say that I’ve never seen another copy of something, that means a lot. Unless someone bought something at a flea market and it went directly into their collection, and it’s somebody I don’t know or they haven’t mentioned it to me, those are the things that I don’t know about. And there are plenty of posters or cards that I’ve only come across once. That Wolf Song is the perfect example. I’ve only seen one copy of that particular lobby card. Lobby cards come in sets of eight, there’s a title card and seven scene cards. I’ve seen the title cards a couple times and I’ve seen the other scene cards, but the one I have in my collection that got me started, it’s the only time I’ve ever seen that card. So when we trade now and I’m with a guy that I’ve known for 30 or 40 years, and I’m saying, “look, I’ve never seen this before and I want that other card over there that I know you’ve never seen another of,” it’s that much more meaningful.

“It’s a bombardment of color and graphic art,” Cleveland said. The exhibition takes over two galleries and is at the Norton Museum of Art through October 29.

So you collect across the movie spectrum?

It goes back to the artwork and to the advice my professor gave me: buy what you love. It doesn’t matter if the market goes up, down or sideways, you’re still going to love what you have. You can’t buy as an investment. If you do that, it always seems to fail. So I’ve always bought on artwork and that’s been my driving force. I have moved toward the norm, as it were, of respecting the best films of all time, the best actors, actresses and directors, and picking things up with them along the way. But by the same token, there are a lot of works I love with stars that no one has ever heard of, that are lost films, but I just happened to love the poster.

How do you display everything at home?

Oh, I don’t. I have a couple posters up that I enjoy and I rotate through them. And that’s what’s really exciting about the Norton Museum exhibition. A lot of these posters are up for the first time, they’re stretching their legs like a girl whose had a pretty dress in the closet but hasn’t had an opportunity to wear it. These posters, seeing them up on the walls of the galleries there, was just an incredible experience for me. Matt Bird, the guest curator, did a really beautiful job of grouping works and telling some stories. I keep everything archived, I’m a real stickler for condition, knowing and documenting what I’ve got. So I keep extensive lists with all of the credit information on all the films, and I keep image files of everything, all sortable in a bunch of different ways. Everything is in archival bags. I’m a condition freak, so I’ll avoid things that have a lot of restoration or need it.

Tell me how the exhibition came about.

I spent 15 years trying to elevate movie posters above the status of movie memorabilia, one to where it’s art unto itself, independent of the films. I’ve approached countless museums and foundations, film schools and festivals over the years, and I finally hit a chord with the Norton Museum. I had a connection with the board president, and I was going to be down in West Palm Beach. So I called up and asked to stop by with a couple posters. He brought a couple curators, I rolled some posters out and we had a 40-minute conversation, which went really well. They asked some great questions, and at the end of it, I rolled up my posters and went on with my business. I had no idea how they were going to respond. This has never, ever, been done before. Posters, in this quantity with classic Hollywood films, have never been in a museum of that caliber. There have been smaller shows, and niche displays, but never this. They emailed me three or four weeks later and said they’d love to do the exhibition. I would have agreed with anything they were willing to put on. As it turns out, it was better than I ever could have hoped for. They didn’t have an expert on staff to launch a responsible show like this, so they got a guest curator from the Rhode Island School of Design, Matthew Bird, and as luck would have it, he’s curated exhibitions for them in the past. And he did just a beautiful job. His background is graphic art and design and that dovetailed with what I was interested in with the posters. Most of the time it’s a film scholar who curates these kinds of exhibitions, so that’s what really made this so special – Bird has a whole different lens to look through and explain with.

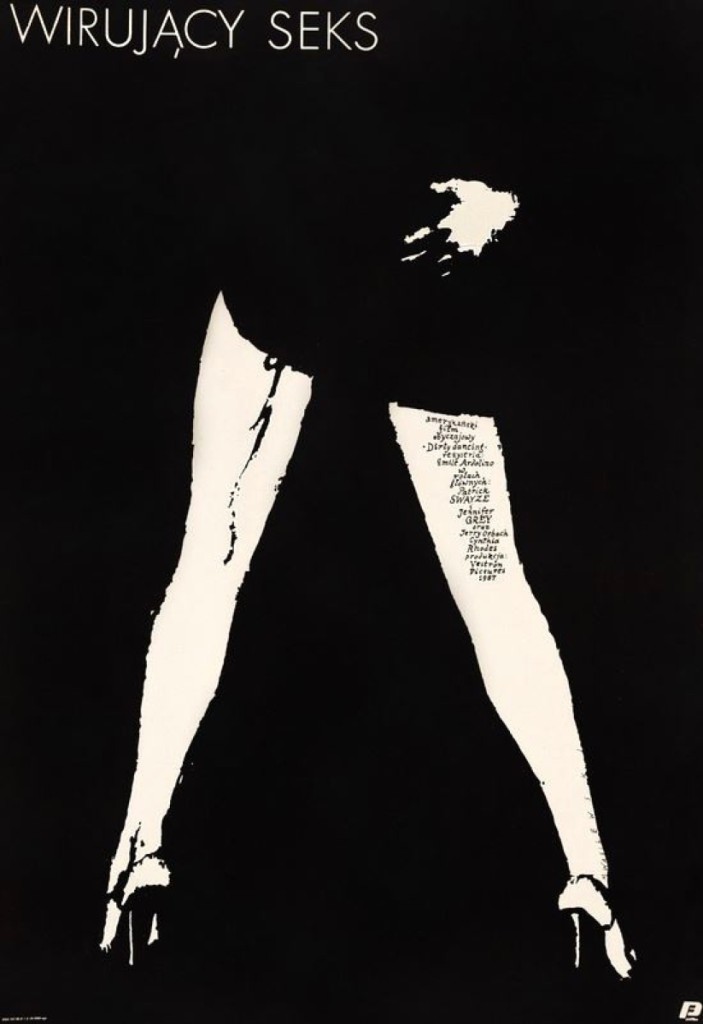

A 1-sheet poster for Dirty Dancing, art by

Mieczyslaw Wasilewski, Vestron Pictures, Polish, circa 1987-89. Film directed by Emile Ardolino, starring Patrick Swayze and Jennifer Grey.

What’s your very favorite poster in the exhibition?

There are 215 and I really can’t differentiate between them. They are all my children and they’re all fantastic. When Matt Bird and Rachel Gustafson, who is the Norton’s staff curator on the show, came out to Chicago, they looked at every single piece of paper I own. They were here for two days and they did a remarkable job selecting only 215. I’m still a little confused as to why all 3,000 couldn’t be in the exhibition! Why not just take over the whole museum! But they used a very critical eye to tell the story they wanted to tell and they narrowed it down. I couldn’t be happier with what they selected. They’re all great. And everyone is going to relate to something different. Individual tastes always fascinate me.

What are some of the other themes in the exhibition?

There’s a section on celebrity, covering the stars from the 1920s and 30s. There is a studio section with Paramount and MGM, those are the two studios that did the best job on artwork with their posters, with the quality. There’s a category on race featuring a poster from Stormy Weather, which was one of the two first all-black cast, big budget Hollywood films from 1943. It’s a great looking poster and it has all the stars. It was really a retrospective. A category on Westerns, a category on foreign posters for American films and another on foreign films. The curators have set up a great wall with all these posters from all over the world; I think there are 19 countries represented. There’s a Dutch poster from Battleship Potemkin, which is one of the most remarkable films of all time, the Russian film by Eisenstein. There’s an absolutely fantastic Mexican poster of María Félix. She was huge, the biggest Mexican film star known worldwide. Just as famous outside the United States and around the world as any American movie star, and it was probably because she never learned how to speak English. She never tried to make it here, she made it in Mexico and she was so beautiful and talented, she became famous just like Garbo, Harlow and Dietrich when she went to Europe. Matt Bird has a section on film poster sizes and he created an “anatomy of the movie” display. He takes this poster from a W.C. Fields film and he breaks it down. He has arrows pointing to different sections identifying what they are. The exhibition is educational, and, the main thing, it’s beautiful. You walk in these two galleries and the ceilings are about 30 feet high, the posters are plastered all over the walls. It’s a bombardment of color and graphic art.

Is poster art overlooked?

Absolutely, there’s no question about it. Fine art people look at posters with an evil eye. When it comes to commercial art, which posters are because they’re advertising films in this case, they use a double-evil eye. It’s treated as a second-class citizen and no one has really recognized it before. That’s what makes the Norton so revolutionary. This is an art form that everybody loves. Everybody loves the movies. Especially in the United States, the bottom line is that film is arguably the most influential art form of the Twentieth Century and now the Twenty-First Century. It’s been one of the United States’ largest exports since the 19-teens. If you want to bring in new people to your museum, you need something new. You need something that people love. And the people that want to see the Rembrandts and the Madonna With Child, they know you’re here and they’re going to come in anyway. If you want to attract new customers to cross the threshold, you need something new, and that’s what makes the Norton so remarkable. There are thousands of people showing up to see this exhibition and they are people that have never been to the museum before. But they hear about it and they think “oh that’s cool, maybe they have some James Bond posters,” which we do, or they’ve heard about some of these foreign posters which are really exciting from a graphic standpoint. And they recognize the names Greta Garbo, Bette Davis or Clark Gable, and they think, “I never thought about going in there before, but I’ll go see that.”

Portrait lobby card for Wolf Song, Paramount Pictures, United States, circa 1929. Film directed by

Victor Fleming, starring Lupe Vélez and Gary Cooper.

What’s one of the most memorable collections you’ve bought from?

I got a call from some guys in Chicago that owned a second home along the border in Indiana in a town called Michigan City. They had started renovating this home and they discovered that the walls were insulated with window cards. It turned out that the owner of the home, in the Depression, in the 1930s, he built little additions onto this home every year or two. In order to save money, he would tell his workers to go down into the basement of his movie theater and pull out a bunch of posters from down there – which are just sitting there and doing nothing – and fill up the walls, using the posters as insulation. So they filled up the walls and put the drywall up and sealed it. They were encapsulated in the walls – this was a discovery I made in the early 1990s. It was a great find.

How many were there?

We pulled out about 6,500 window cards from there. There was one big purchase and then there were multiple purchases after the initial one. They wouldn’t let me tear everything down at once. I got the bulk of it, it was me and another guy with the first big bulk, and then after that I guess they preferred dealing with me, I was closer to them, and they would call me when they were doing other little projects and when they found things.

The house that kept on giving.

Yes, it was great. There were works in there that have never been seen again; it’s the same story when we make these finds. It’s all so rare because the posters only had a shelf life of a couple days where they advertised the film. And then it became garbage – it wasn’t useful to anyone, so it got burned or thrown out or recycled during World War I or World War II. Movie theaters were notorious for turning the heat off at night, so they broke pipes and that flooded the basements, usually where posters were thrown. It’s a miracle any of this has survived over the years.

Poster printing techniques have changed over time, which one stands out to you as the most remarkable?

Clearly stone lithography, which is where it all began. That was an incredibly expensive and laborious method of printing posters but it resulted in these incredibly rich colors that are so amazingly attractive and beautiful. The way that worked, simply put, they had these big pieces of limestone that were the same size as the poster. They would use this waxy crayon to draw a certain image onto the stone, and then they would apply ink to it, and the ink would float on the wax, so when you rolled onto the wax that ink would then affix to the paper. They would repeat this for every single color for every single poster. So you can imagine, they were running off a couple thousand of these posters, and each one had to be done individually. After each color, they would wash the stone, and then apply a different image with the waxy ink and then again run all of those same posters that they had done the previous color on. When you think about it today, it’s just mind numbing the amount of labor that was involved with this. The posters from that time period are just stunning and there really isn’t anything that compares to them.

A 1-sheet poster for Stormy Weather, 20th Century Fox, United States, circa 1943. Film directed by Andrew L. Stone, starring Lena Horne, Bill Robinson, Cab Calloway, et al.

Are those typically the most valuable?

No, they are to some people, but most people don’t buy based on graphics. Most of the collectors from the very beginning, and even now, are film people. So they have a favorite director or they collect on a genre. Universal Horror collectors are the most rabid group of people. They tend to spend the most money and be the most obsessed with it. There’s a lot of wealthy people in that category and those works tend to go for some great prices. Dracula, Frankenstein, The Wolf Man, King Kong, titles like that, are the front runners in terms of value. But there are a lot of people who collect on a particular star, like Humphrey Bogart, or they collect on a director like Hitchcock, so there are various little niches. I’m nondenominational in that I collect it all. What I love is the guiding light.

What are some of the niches that you’ve explored in your collection?

I love lobby cards and I have a big collection of them. I’m what’s called a “completist,” a word of art, and what that means is that I want the best card from every film a star was in before they became famous. I collect male and female stars from the 1920s and 1930s, so I want the best lobby card from the set of eight. So for Humphrey Bogart, he was famous for Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon, African Queen with Katharine Hepburn and a bunch of films in the 1940s and later, but he made a lot of films in the 1930s before he became super famous for this character of a gangster, so I’m a completist on Bogart. I want the best card of all those films from the 1930s that no one has ever heard of, and a lot of them, quite frankly, are forgettable films. They were not great performances. But for me, I still want the documentation of his career from the 1930s into the 1940s. As it relates to lobby cards, I’m not that interested in titles after the 1940s. When it comes to the big paper – which is anything other than a lobby card – that’s where most of the artwork comes in. There isn’t that much recent work that I love, but I will collect works from the 1950s, 60s and 70s and a spattering of titles after that. One of the posters they have in the exhibition is a Polish poster from Dirty Dancing, the 80s film, and it’s just a remarkable piece of graphic art that I really love. It communicates the message of the film in the most effective way.

Is there any one piece that eludes you?

Yes, but I don’t like to talk about what I want!

Right, because a seller will see it…

The price tends to go up if someone knows I’m looking for something! I will tell you this, most of what I end up buying these days are works I never knew existed. From the silent era, usually some beautiful lithograph or from a silent or early talkies movie star that I haven’t seen before and I didn’t know I wanted because it has never come up before. I go to conventions, talking to collectors and dealers, and I’m offered things all the time while out there poking around. I still make finds, most of this is one of a kind. When I see it, hopefully I’m the first one to get to it and I’m able to acquire it.

It’s hard to believe there’s not a museum dedicated to the movies.

There is, it’s being built now, 30 years in the making: The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles. And they haven’t been able to raise all of their funds for the bricks and mortar. They bought the old May Company Building, which is an old Art Deco structure, and they’re renovating it. It’s going to be an homage to American film, due to be completed in 2020. They have not raised all the money, but they have a great collection so far. I’ve donated a bunch of stuff to them over the years.

I think I’d like to recruit you and some friends for a movie trivia night at a pub. We’d probably have to call a cab afterwards.

I know a fair amount, but there are a lot of people who come at this from the film business and they know a lot more than I do. I’ve learned it through the years through osmosis, and I’ve learned to love the movies, but it’s the graphic art first. I’ve won some bar bets with some obscure knowledge for sure, but there’s a lot of people in this who know so much more.

-Greg Smith